Morning trains disgorge their commuters into the city — white men in suits. Departing trains take Black souls to service white suburban privilege. At dusk this separate and unequal ritual reverses.

This was the Chicago of my youth, a city that Martin Luther King denounced as "the most segregated city of the North." Apartheid Chicago. And so it remains. King stated that compared to Mississippi or Alabama, "I've never seen anything so hateful and so hostile as Chicago."

I attended an integrated high school. There I acquired a lifelong reverence for Black Literature and African American History. For many whites this curriculum was heresy. And for some, so it remains.

James Baldwin and W.E.B. DuBois were classroom epiphanies, but in the cafeteria James Brown ruled. We'd spin 45s from Stax, Vee-Jay, Atlantic and Motown. By 1968 Chubby Checker's Twist was passé. We were doing Watusi, Boogaloo, Mashed Potato and Walkin' the Dog. It was our land of a thousand dances.

At night I'd tune to WVON-AM ("Voice of Black Chicago") on my transistor radio listening to the latest from the Temptations and Staple Singers. For me, a white kid from blue collar burbs, this music was transfiguring.

"Without music the civil rights movement would have been a bird without wings." — John Lewis

Black Gospel was the traditional music of the Civil Rights Movement. The Illinois Central exodus of Great Migration refugees bequeathed us blues from Blind Lemon Jefferson to Muddy Waters. Strangers in a strange land, a dream deferred. But it was music of the children of these Southern diaspora parents that resonated in 1960s Black streets as Baldwin's "fire next time" consumed Watts, Newark, Detroit and Chicago.

I can still hear the sounds from those days of rage and audacious hope:

"STRANGE FRUIT"

BILLIE HOLIDAY (1939)

The haunting lament about lynching reamins resonant. "Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze." The lyricist was Abel Meeropol, a Jewish high school teacher who taught James Baldwin and adopted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg's sons. The last documented lynching in America was 1981. The U.S. did not formally criminalize lynching until 2022 with the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act.

"A CHANGE IS GONNA COME"

SAM COOKE (1964)

This classic came about after Cooke was refused accommodations at a whites-only Louisiana Holiday Inn. Cooke protested and was arrested for "disturbing the peace."

"PEOPLE GET READY"

CURTIS MAYFIELD (1964)

Trains in Blues repertoire are harbingers of deliverance or despair, like Robert Johnson's 1937 "Love in Vain." Mayfield's Gospel entreaty "to get on board" is a metaphor for the locomotion of civil rights.

"DANCING IN THE STREET"

MARTHA & THE VANDELLAS (1964)

In Mark Kurlansky's 2014 book Ready for a Brand New Beat, Mickey Stevenson — the song's Black lyricist — said it was about integration. Sure worked its magic in our high school cafeteria.

"SHOTGUN"

JR. WALKER AND THE ALL STARS (1965)

The song draws its inspiration from a dance at Walker's Detroit gigs. Dancers pantomimed firing guns, others doing a twitching Jerk. "Shoot 'em 'for he run now." Is it veiled allegory about cops gunning down Blacks with impunity echoing in the shootings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky? Or it is an iteration of the traditional Blues ballads of love betrayed and avenged such as Leadbelly's 1944 "Where Did You Sleep Last Night?"

"RESPECT"

ARETHA FRANKLIN (1967)

Etta James said the song was about the domestic violence Franklin endured. Aretha, like Tina Turner, escaped her abusive husband. "I'm about to give you all of my money / And all I'm askin' in return honey / Is to give me my profits." Franklin equivocated that her cover of this Otis Redding standard was only about the respect all deserved.

"SAY IT LOUD: I'M BLACK AND I'M PROUD!"

JAMES BROWN AND THE FAMOUS FLAMES (1968)

If Aretha was the "Godmother of Soul," Brown was its "Godfather." His tight orchestration and stage swagger were shamanistic. By the time this was recorded, Muhammad Ali had resisted the draft to Vietnam, MLK and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated, and the Civil Rights Movement was becoming more militant. Black scholar Mark Anthony Neal contends that the song emerged from criticism of Brown by the Black Panthers that "he wasn't Black enough."

"WHAT'S GOING ON?"

MARVIN GAYE (1970)

Gaye was responding to Black soldiers who like his brother returned from Vietnam confronting double disgraces — fighting an "unjust imperialist war" and racial discrimination. "Don't punish me with brutality."

"STAND!"

SLY AND THE FAMILY STONE (1969)

Sly Stone's sense of theater was mesmerizing, as was Cynthia Robinson's trumpet playing. The Family Stone stood out as the first major Black band to integrate with white musicians. At Woodstock, Sly emerged onto the stage like an electrified, psychedelic Mummer or Zulu sangoma exorcizing his white audience. A 2022 oral history of the band effused: "There was Black music before Sly; then there was Black music after Sly," (For more, watch the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.)

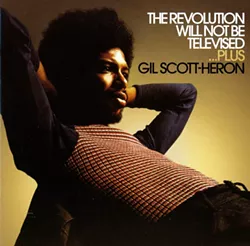

"THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TELEVISED"

GIL SCOTT-HERON (1971)

This is black beat — its spoken word poetic assault on racism and capitalism as incisive as Allen Ginsberg and Amiri Baraka. As Scott-Heron implies, perhaps "the revolution" had as much to do with television as Malcolm and Martin.

If a Black person lived in a ghetto, they likely could not afford the ticket to the white Norman Rockwell American Dream. But they could see the stark, enraging difference between their poverty and the white picket fence idyllic fantasy of Leave It to Beaver. It seemed a perilous, uncrossable abyss.

Consider the tribulation of Walter Younger in Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun (1959). And if they labored in the suburban McMansions of the commuting Willy Lomans, they encountered an apparently halcyon existence that even few working-class whites could attain. A Chicago native son, Scott-Heron is regarded by Chuck D and other hip-hop artists as rap's Godfather.

SPACE IS THE PLACE

(ALBUM, 1973; FILM, 1974)

Sun Ra and his Arkestra would never make the WVON playlist. This is the musical wilderness, the sounds that resist the domestication of caged commerce and categories critics crave. That conceded, Chicago's Sun Ra is regarded as an "avant-garde jazz artist," the genre dominated by Pharaoh Sanders, Ornette Coleman, Roland Kirk, John Coltrane and Mile Davis. Sun Ra occupies a jazz subgenre hinterland called "Afrofuturism."

Afrofuturism was birthed from space exploration and sci-fi popular culture. The post-apocalyptic dystopian world of sci-fi resembled the past and present racism and despair of Black lives. And Space is the Place — the sci-fi feature film and its soundtrack — captures that.

Similar to George Clinton's Funkadelic sound, for Sun Ra the future was Pure Funk, a mystical, wildly oscillating music, its acolytes Afronauts who struggle spiritually with aliens representing racism and who colonize planets, today no less imaginable than Marcus Garvey's "Back to Africa" movement was in the 1920s.

Later I realized that the Black music I revered had been appropriated by white artists, an insidious variation of Jim Crow sharecropping. Alas, these songs are the mother of all American music. How could it be that everyone knows Led Zeppelin's "When The Levee Breaks" but Memphis Minnie's 1929 original is invisible? If the present derailed arc of history is to be righted on a just course, we need to be dancing in the streets. ♦

John Hagney is a local historian who taught high school and college history for 45 years.