It's easy to digest cultural history when reading it in a book. It's simple for scholars to lay things out in a way that makes sense as patterns emerge and the passage of time allows for a broader perspective. The people involved become characters — relics of the past who can be boiled down to a few lines rather than the complex living and breathing people they were.

Actually living through a cycle of cultural history is much more complicated.

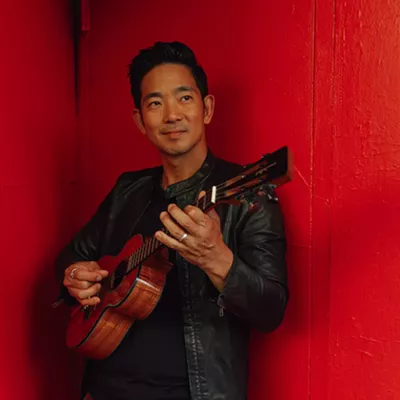

When singer-songwriter Israel Nebeker started the band Blind Pilot with drummer Ryan Dobrowski in the mid-2000s, the then-Portland-based duo was just playing the type of music they and their friends enjoyed. Blind Pilot's 2008 debut album 3 Rounds and a Sound radiates an easygoing sonic warmth. Combined with Nebeker's emotionally thoughtful lyrics, it's an album that quickly caught on with the mildly crunchy and contemplative Pacific Northwest collegiate crowd.

Blind Pilot — which expanded to become a six-piece band with bass, banjo, trumpet, vibraphone and more — was just making the kind of music that appealed to its members. But it turns out they weren't the only ones in the region on a similar wavelength.

The mid-2000s saw a massive Pacific Northwest indie folk boom. Fellow Oregonians like The Decemberists, Blitzen Trapper, and Horse Feathers emerged around the same time that Seattle Sub Pop bands like The Head and the Heart, Fleet Foxes and Band of Horses broke out on a national level. There was a Cascadian quaintness that Blind Pilot and their PNW peers all shared — Blind Pilot even did bike tours. Nebeker and Dobrowski would pedal long distances to take in the beauty of the evergreen-strewn West Coast between gigs.

But it wasn't long before a version of the booming scene grew beyond them and became commodified into a stomp-clap pop movement and a style that could be peddled as a hipster aesthetic. This commercialized indie folk might've been parroting some of the same notes as the PNW indie folk scene, but it was an entirely different bird. Needless to say, this shift was a bit of a headtrip for Nebeker.

"I studied art history in school. It's one thing to conceptually understand how art movements flow and how it always works and changes and morphs into the next thing. It's a different experience to be a part of something," Nebeker says.

"We were really lucky. There wasn't a scene for what I was drawn to making at that time. We got to be at the front of a big wave that we didn't even know was forming. It was just what we were attracted to and some of our friends were attracted to. Looking back on it, it was exciting to be there and to be part of a scene and to be like a buzzy band — that was amazing, that was a dream come true. But it also was deeply disturbing by the time every Brooklyn kid musician putting on overalls in a straw hat and speaking with the Southern accent on stage. It was like, 'Oh man, we need to get out of this.' [Laughs]"

"It was actually difficult to be in that moment for me, because I knew conceptually that this is just how art movements work — they're alive and thriving and bringing a potent message for just a couple of years, maybe three or four at most, and then it's onto the next thing," he continues. "But to be part of it, it was artistically really challenging. I felt resentment for everybody that was commodifying something that felt really valuable, and now we were forced to either be a part of the song and dance or move on to the next thing, which we didn't want to. We liked what we were doing."

After releasing two more LPs — 2011's We Are the Tide and 2016's And Then Like Lions — Blind Pilot mostly dropped off the radar until this year. August saw the release of In the Shadow of the Holy Mountain. The album showcases a group that hasn't lost a step, whether it's the opening exuberance of Nebeker retracing his roots ("Jacaranda"), an outdoorsy rumination on the stories that continue across time ("Pocket Knife") or tender homespun love songs ("Don't You Know"). While the now-Astoria, Oregon-based Blind Pilot hadn't been planning to take such a long time off, part of the delay was just Nebeker just finding his songwriting spark again.

"I was trying for some years to bring songs in, and they just didn't really want to come," Nebeker says. "One major pivot was I gave myself permission to write songs for a solo album, rather than writing for Blind Pilot. And immediately, a lot of songs started coming through. But I was very much not looking forward to the conversation going to my band and saying, 'Thank you so much for waiting for me for like five years, but I am going to record a solo album instead.' And so the second pivot that came was that notion that now that I have a solo album written and about to go record, I could devote the month of July [2023] to writing for Blind Pilot, and it could just be whatever comes out in that month."

While Nebeker's songwriting drives Blind Pilot, the process of making Holy Mountain was largely one intended to decentralize him from controlling every aspect of the process. The band employed producer Josh Kaufman to make the new album, which allowed Nebeker to step back from a guiding role. The results lead to an album that showcases the band as its own living entity, instead of being so songwriter focused.

"I've always known that the music will sound best if everyone gets to be their authentic self in the song together — if everyone gets to bring what they do best, musically and energetically," he says. "But it gets really tricky when you're a songwriter, because you're also obligated to the song. You have a stewardship role for the song. And sometimes those things conflict. I didn't feel that conflict at all in this album's whole process. It just flowed."

The swift songwriting window also allowed Nebeker's songs to unfold within his own brain differently. While prior Blind Pilot albums featured autobiographical songs that he'd honed over years and understood with a craftsman's sense of complete comprehension before ever bringing them to his bandmates, some of the themes on Holy Mountain didn't even become evident to him until the album had been fully completed.

"I was listening back to it with some friends, and it just hit me really hard how much of the album has to do with my own story as it mirrors and relates and reflects my family's ancestral story and stories in my family," he says. "That's a pretty big through line."

That story is, in part, one of the Sámi, an Indigenous people of the Scandinavian region. Nebeker can trace his lineage back to the Sámi, but also those who caused the Sámi suffering.

"The Sámi hold a pretty similar recent history as Native Americans: land taken, pushed into less desirable land, and children taken from families, Christianized, all that. That's definitely part of it. Also my mom's side of the family is Jewish from Ukraine — pretty intense trauma with pilgrims in Ukraine and starvation and things like that," Nebeker says. "But I also gotta say, on my dad's side I'm Sámi, but I'm also Norwegian. I come from this oppressed group, I also come from the oppressors. And I think that's pretty important to understand, that we all hold trauma in our family line. That's the story of our world, collectively."

After the long unintentional hiatus, Blind Pilot is excited to get back out in front of fans to share these Holy Mountain tunes and revisit old favorites. Blind Pilot heads — not by bike — to the Bing Crosby Theater for a concert on Tuesday, Nov. 26. Nebeker has been thrilled that folks still care about his band's music.

"We weren't really sure where our fan base was going to be at by the time we were back on the road. And, you know, it's a very different musical world than it was when we put out our last album in 2016," Nebeker says. "But it has been really encouraging and truly just overwhelmingly amazing to have fans show up and be glad to connect with us still after a lot of years."

Blind Pilot might no longer be riding the cresting wave of the mid-2000s Pacific Northwest indie rock boom, but there's still plenty of musical joy to be found in calmer waters.

Buzz fades, but authenticity does not. ♦

Blind Pilot, Molly Sarlé • Tue, Nov. 26 at 8 pm • $30-$165 • All ages • Bing Crosby Theater • 901 W. Sprague Ave. • bingcrosbytheater.com