I'm watching a pale, androgynous figure gyrate on an oversized, grainy tube TV in 1998. They, along with several white-masked figures, are dancing in front of the same building I know from the first season of Power Rangers. It's the building from which the floating-headed, space alien guru Zordon commands his army of child soldiers against his immortal space witch enemy, Rita Repulsa. My dad flips the channel away from MTV2, explaining that this Manson guy was just another musician trying to make a career out of pissing parents off.

A few years later, watching VH1, I'm introduced to W.A.S.P. in a similar manner. My dad and I again have a similar, though mildly more nuanced, conversation about shock rock. I won't think about W.A.S.P. again for close to two decades. The world was already changing after we watched something like a televised national beheading on 9/11: A new age of perpetual shock was being born, screeching into the world like a saw-bladed codpiece through pleather.

"I Wanna Be Somebody, Be Somebody Soon"

Rearing its ugly head from the vile womb that was the early '80s LA hard rock scene, W.A.S.P. emerged in 1982. While the band partook in all the required gender-bending, glam rock accoutrements, the group set itself apart by its edgier subject matter, heavier riffs and wild stage antics. While bands like Motley Crüe and Poison veered hard into the pop-friendly "glam" side of things, W.A.S.P. dove headfirst into shock rock with lust, male power fantasies and a bunch of raw meat in hand.

At the time, Alice Cooper had already been shocking the masses for a decade with his on-stage beheadings and rejections of authority with tracks like "18" and "School's Out." David Bowie, for his part, had been challenging gender norms with queer anthems like "Rebel Rebel" and "John, I'm Only Dancing." Earlier than both of them, Screamin' Jay Hawkins released tracks like "I Put a Spell on You," a violent-sounding love song filled with guttural screams that could be thought of as the first head to roll in the genre.

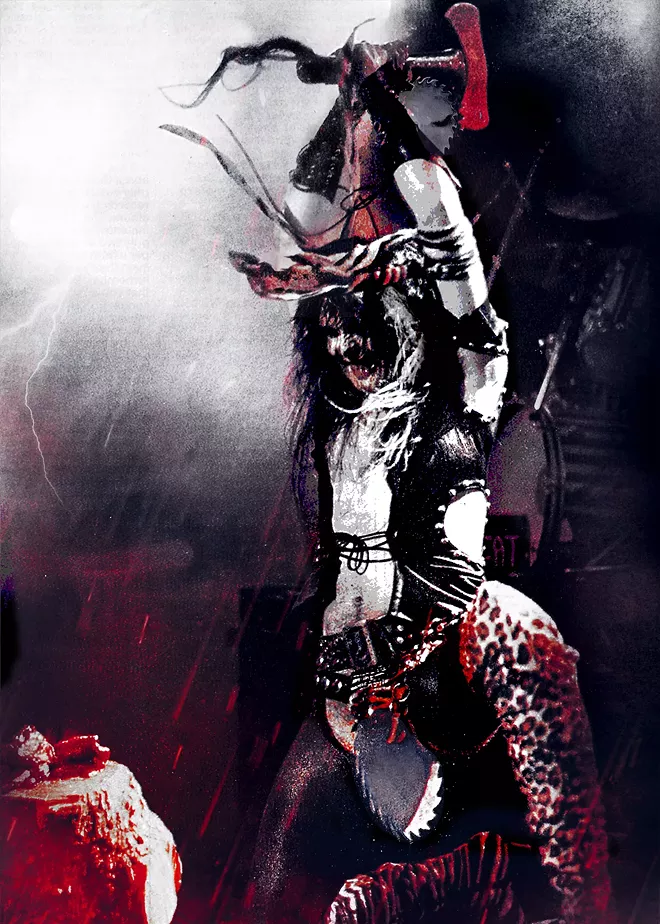

While the base chemicals — cultural critique, horror-leaning theatrics, and heavy music — formed the DNA of shock rock, W.A.S.P. was a new beast. Blending these elements, W.A.S.P. roared onto the national scene with the release of "Animal (F— Like a Beast)" in 1984. Led by frontman Blackie Lawless the band's live show pushed the limits at the time. Blackie notoriously threw raw meat into the crowd and performatively tortured a naked woman on stage — an act so scandalous it earned the band death threats.

"Animal (F— Like a Beast)" raised the hairs of Tipper Gore's Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) pro-censorship crew, earning a place on its "Filthy 15" — a list of tracks that got parental panties in a bunch... which also provided young'uns a place to start if they were looking for music sure to piss off their parents.

While the PMRC won the battle to get Parental Advisory labels on "objectionable" albums before disbanding in the early 1990s, the Karen crew clearly lost the war. The artists in their crosshairs were far from harmed. The "Filthy 15" included many of the most prominent artists of the time, ranging from pop icons like Madonna and Prince to black metal pioneers Venom and Mercyful Fate — artists whose legacies far outlived the short, sad life of the PMRC. The ghosts of PMRC may still be sending shivers down our spines — "heretical" forms of personal expression or critique of our white Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture will always be under attack — but that's a different hornet's nest to kick on another day.

"The Torture Never Stops"

Electroconvulsive therapy, or shock treatment, is used to treat all sorts of mental illnesses, mostly depressive disorders. A shock of around 100 volts is administered to the patient's head. The effects are similar to general anesthesia, creating a sort of numbness, and there's another common side effect, too: retrograde amnesia. The shock erases information that occurs before the event and during it. It's part of what makes the procedure so effective; this compounds when shocks are administered repeatedly.

Isn't this how so many of us view the last 20 years of history? A series of successive shocks that have left us relatively numb, blurred together into a vague sense of disorientation and desensitization. We can't even seem to agree on where we are morally, politically, economically, much less how exactly we got here. Twenty-plus years of shock treatment to the collective unconscious will do that.

"Cause Dead Boys are Martyrs That Live on Forever"

Marilyn Manson was, in my estimation, the last great shock rock artist. His industrial-meets-nu-metal strain of shock rock was as indebted to the genre's history as it was prescient of so many current cultural battles. The mental health crisis and our cultural overmedication. The transgender movement and rejection of established gender norms. Our dependence on technology for dopamine distribution. School shootings.In many ways, this character — Marilyn Manson — performed by Brian Warner, metaphorically died on 9/11, too. When he released his follow-up to his 2000 post-Columbine album, Holy(Wood), The Golden Age of Grotesque, he did so with a subtle rebrand. Far less shocking, he appeared in a retro, 1920s get-up. The music was less heavy, less extreme, more palatable for the masses. The only true shocks he's provided in recent memory come via reading the litany of assault allegations leveled against him. As Manson began to fade, so too did shock rock as a virile genre.

"She's a Lesbo-Nympho Maniac"

Jumping ahead 20 years to 2020, we now have popular songs like Cardi B's "WAP," which one might argue is in the tradition of shock — at least as the PMRC might define it. It certainly sent Ben Shapiro into a tizzy with its references to basic female anatomy and autonomy. "WAP" stirred some pots and was a hot topic track for a minute, but a pro-sex feminist anthem isn't anything we haven't heard before. Nine of the "Filthy 15" were scrutinized by the PMRC for "sex," and the majority of those (five) were by female artists. This is to say, they were particularly concerned about policing notions of female sexual empowerment.

To those culture warriors' absolute displeasure, Chappell Roan has risen to superstardom this year. Glamorous and theatrical, Roan incorporates elements of drag culture, casually sings about receiving oral sex on pop hits, and criticizes hetero-patriarchy in a way that probably makes JD Vance queasy. Maybe sick, even.

But probably not shocked.

I don't even think my grandmother, who made my Dad scratch "Shout at the Devil" off his vinyl with a key, would really be shocked by any of this anymore. Unlike most things these days, shock is one thing in overabundant supply and insufficient demand.

"Never Gonna Quit Before My Time"

By the time I was born, W.A.S.P, led by the gradual moral awakening of Blackie Lawless, had already moved on from trying to shock the world. Death threats will do that to you. I wouldn't rediscover them until a few years ago, neck deep in curating a heavy metal playlist for lifting weights. The ridiculous, tongue-cheek lyrics definitely drew me in — they're good for a quick chuckle — but it was the musicianship that kept bringing me back.With his unique, quasi-feral inflection, Lawless was one of the more interesting singers of the time. He brought a certain edge that made Vince Neil and Bret Michaels look like, well, Vince Neil and Bret Michaels. And that's not to mention the mean-manned twin guitar package that was Chris Holmes and Randy Piper. Blackie Lawless is still leading the pack. While he probably won't be slinging any raw meat into the crowd, I have it on good authority that there will still be plenty of heavy metal. W.A.S.P. may no longer be so shocking — nothing seems to be in 2024 — but the band is still rocking. All you need to do is bring your own meat. ♦

W.A.S.P., Armored Saint • Sat, Nov. 2 at 7 pm • $40 • All ages • Knitting Factory • 919 W. Sprague Ave. • sp.knittingfactory.com