Richard and Karen Carpenter sit by the ocean, dressed in dinner-party duds and beaming directly into the camera lens, which is pulled to the softest possible focus. The photo on the cover of the Carpenters' 1970 album Close to You is like something you'd see hanging in a Sears portrait gallery (Richard himself hated it), and that gauzy, clean-cut image dogged the duo for years.

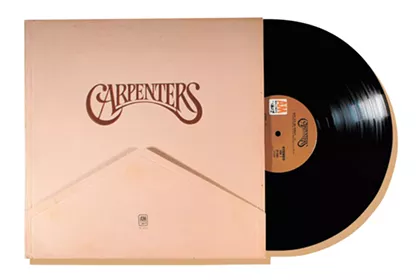

A year later, the Carpenters' third LP would have nothing on its cream-colored jacket but the band's name, embossed in its now-iconic baroque font. That record, simply titled Carpenters, was released 50 years ago this week, and it cemented Karen and Richard's status as (pun intended) superstars. It remains their most successful studio record, too, selling more than 4 million copies and spawning three Top 10 singles.

The brother and sister duo simultaneously embodied the sunniness of their Southern California home and the buttoned-up wholesomeness of their middle-class Connecticut upbringing. Richard arranged the songs and played piano, occasionally taking lead vocal duties but mostly providing harmonies for Karen, who also played the drums. They cut their teeth as part of a jazz trio but struggled for recognition until they drifted toward pop, eventually being signed to A&M Records by Herb Alpert.

By many accounts, Karen resisted the role of singer, not wanting to step out from behind the shield of her drum kit. But it was her distinctive voice — as crystalline as it was crystal-clear, dripping with world-weary melancholy one moment and wide-eyed wonder the next — that became the group's calling card.

The Carpenters' debut album, initially titled Offering, went mostly unnoticed in 1969, save for its minor-key cover of the Beatles' "Ticket to Ride." Close to You followed the next year, and it included such signature hits as "We've Only Just Begun," which Richard first heard as a jingle on a regional bank commercial, and the chart topper "(They Long to Be) Close to You," written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David.

When Carpenters landed in record stores in May 1971, its blockbuster status was a foregone conclusion. A couple months earlier, the group had won the Grammy for best new artist, beating the likes of Elton John and Anne Murray, and the LP's lead single, the Paul Williams-penned "Rainy Days and Mondays," had already shot up to No. 2 on the Billboard charts.

"Rainy Days" is one of the best-known tracks on Carpenters, and the album also includes more minor Carpenters classics like "Let Me Be the One" and "For All We Know," an Oscar winner that first appeared in the long-forgotten ensemble comedy Lovers and Other Strangers. "(A Place to) Hide Away" is a beautiful piece of melancholy, with Karen's voice at its most resonant.

Side B is dominated by its lead-off track, "Superstar," arguably the Carpenters' greatest song, though they weren't the first artists to tackle it. The original version was recorded by blue-eyed soul duo Delaney & Bonnie with assistance from Eric Clapton, and was called "Groupie (Superstar)," a title that was clearly too suggestive for Richard and Karen. Co-written by Leon Russell, it's the story of a fan who has a one-night stand with a rock 'n' roller and then finds herself haunted by him. She thinks he's come back to her, but it turns out she's just hearing his song on the radio.

The Carpenters' version isn't too different from the Delaney & Bonnie original, but it has a chillier air of desperation, with Karen's recurring lament of "baby, baby, baby, oh baby" aching with loneliness. The song even ends on an unresolved minor note, an unsettling melodic choice, as if its protagonist will always be waiting for something that will never come. It's a masterful pop song, one I listened to no less than a dozen times while working on this piece, and a remarkable showcase for Karen's haunting voice.

"It is a voice that seems to resonate with a maturity beyond the scope of vocal chords only 23 years old," reads the booklet tucked inside the sleeve of my old vinyl copy of The Singles: 1969-1973. "Even given the extraordinary amount of talent emerging from the 'Soft Rock Revolution,' [Karen] is one of the finest singers of this generation."

It's true. It's easy to heap all this praise on the Carpenters 50 years removed from their creative peak, because they're revered now. I grew up with their music and know many of their songs by heart, having heard them over and over again on cassette tapes and oldies stations. But they were something of a punchline at their peak, a shorthand for edgeless, sexless soft rock, projecting a skim-milk innocence that was at odds with the political turmoil of their era. Rock critic Lester Bangs called their stage presence "disconcerting." Robert Christgau knocked them as "dispassionate" and chalked up their popularity to some kind of algorithm.

By the mid-'70s, the Carpenters had fallen out of fashion, though they still scored hits on the adult contemporary and country charts. Things were even darker behind the scenes. Karen was struggling with anorexia nervosa, and she was devastated by a tumultuous divorce and the cancellation of a solo debut. Richard, meanwhile, was in and out of rehab, battling an addiction to quaaludes. Though the group's final album, 1981's Made in America, produced the hit song "Touch Me When We're Dancing," they were far from their zenith.

Karen died in 1983 from heart failure. She was only 32. Her death no doubt inspired a serious re-evaluation of her work, not only as a vocalist but as a virtuoso drummer, and the unflinching sincerity of her music plays so much differently now. In her book Why Karen Carpenter Matters, writer Karen Tongson (herself named after Carpenter) describes the effect of Carpenter's artistry as "the capacity to make you feel something, to make you believe in a spiritual undoing and trembling beneath the polished arpeggios and vacuum-sealed harmonies."

As with much considered kitsch in the '70s, the group has since achieved hipster cred. Todd Haynes' 1987 short film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, which told of the band's rise and fall with a cast of Barbie dolls, married kitsch and sincerity as both a behind-the-scenes biopic and a scathing indictment of the image-obsessed music industry. Then there was the 1994 tribute album If I Were a Carpenter, which featured alt-rock icons like Matthew Sweet and the Cranberries covering Carpenters classics. The 2007 film Juno prominently featured the album and Sonic Youth's interpretation of "Superstar," which made the original's fuzzy radio reverie even fuzzier.

Just last week, a clip of Karen behind her drum kit, slapping the skins in a jazzy rendition of "Dancing in the Street," went viral on Twitter, being viewed nearly 4 million times and retweeted more than 30,000 times. People are still discovering that she and Richard were more than just toothy grins and harmless vibes, that there was real artistry behind their work. The Carpenters' tune is a timeless one, and it will always be playing on the radio — baby, baby, baby, oh baby. ♦