Even now, after releasing their final set of maps a day after the Nov. 15 deadline, the Washington State Redistricting Commission's work has continued to spark bitterly divided debate between partisans: One side argues that Monday night's final meeting was a train wreck; the other argues it was more of a dumpster fire.

A few mavericks see it as more of a boondoggle, with the occasional holdout describing it as a shit show.

But this much is undeniable: As the clock chimed midnight to end Nov. 15, the redistricting commissioners, after conducting intense negotiations in private over proposals the public hadn't seen, were voting on a plan that may or may not have been legal in support of redistricting maps that didn't actually yet exist.

Clear?

On Tuesday morning the commission acknowledged it had officially missed the final deadline, meaning the final redistricting maps, as required by state statute, will be designed by the Supreme Court.

But the Supreme Court is just as confused about what happened, ordering the

But even the chair doesn't quite know exactly what happened that night, she tells the Inlander.

"What I know about their negotiation is what the public knows," she says.

The Inlander has compiled a non-exhaustive list.

1. The census data came in very late.

The entire purpose of a redistricting process is to draw each legislative and congressional district so they all have equal populations. Every 10 years, a new census is released, and the borders have to be drawn.

The census data had been expected by April 1 at the latest. But the release of the data was dramatically delayed, thanks to COVID and decisions made by Donald Trump.

"We got it in August," Augustine says. "It's not like we were wasting time. I feel like we adequately used very effectively all the time that we had. But we had a very short period of time to do the actual mapping with data."

2. Washington state voters passed an initiative to move the deadline sooner.

But that "meant some of the most important time for public input fell during Thanksgiving and the holidays," Riccelli says. So in 2016, with the widespread support of the Legislature, voters changed the law to move up the deadline to ensure that input would happen earlier.

"Washington has one of the nation’s best redistricting systems," wrote a bipartisan group of legislators in support of the initiative, arguing that shortening the deadline would make the great system even better. "This simple yet important change shortens a yearlong process by six weeks, offering benefits to voters and taxpayers alike."

What could go wrong?

"It was an 80 percent reduction in the amount of time you had to do it," Fain says between yawns. "Ten months of reduced amount of time to work on it led to being one day late."

When the draft redistricting maps came out at the end of September, the Democratic commissioners were particularly proud of the way, as they saw it, their legislative maps gave a voice to more minority communities.

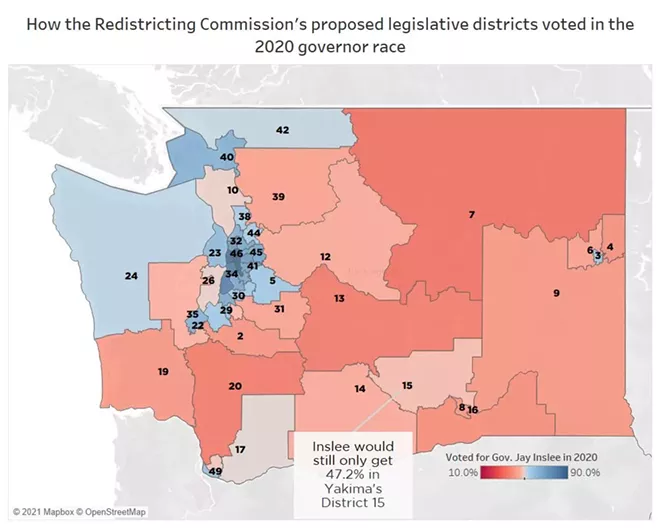

But in the Yakima area, Crosscut reported in October, their maps may have fallen short of the standard required by the Voting Rights Act — and Republicans' maps were even worse. In the 1980s, the Supreme Court established what's called the "Gingles" test. To oversimplify a bit, if there's a large enough clustered group of racial minorities in a certain region, and that group votes in a racially polarized way, a district must be drawn to give that group a decent shot at electing their preferred candidates most of the time.

Even the map drawn by the Senate Democrats' Redistricting Commissioner Brady Walkinshaw — the first Latino commissioner to serve on a redistricting commission — didn't meet that standard, according to an analysis commissioned by Senate Democrats.

Part of the challenge is the metric you use. If you just looked at the total percentage of the Hispanic population in District 15 in Republican Commissioner Paul Graves' proposal, it may have looked like he met the standard with 54 percent of the population. But if you look at the percentage of Hispanic citizens of voting age — a lot more relevant to the election — the total is radically different, one expert told Crosscut: Only 36 percent were Hispanic.

This became a key point of contention: Republicans didn't want to just let a traditionally Republican voting district in Yakima turn into a Democratic voting district without getting something in exchange.

Republicans countered by commissioning their own legal analysis from a different set of experts who, as you might not be surprised to hear, came to a very different conclusion about the law.

Meanwhile, Republican commissioners focused on trying to make more districts electorally

competitive, a part of the redistricting law that Democrats seemed to simply shrug off.

Ultimately, the Democrats and Republicans fought to a standstill on the issue — their final statewide legislative map is about as competitive as the current boundaries are. 5. The penalty for failure wasn't equally threatening to all sides.

If you're a Republican, the last thing you'd want is for the state's legislative and congressional districts to be decided by Washington's famously liberal state Supreme Court. But if you're a Democrat would that be so bad? Even the knowledge of that fact could spark speculation and distrust.

Both Fain and Augustine told the Seattle Times on Wednesday that Walkinshaw, the Senate Democrats' commissioner, didn't seem quite as engaged in trying to reach a deal as the others, though Walkinshaw denied that he was ever trying to sabotage the deal. After all, he ultimately signed on to unanimously support the map as well.

"My approach was to do a regional approach, where there would be teams, and they would take it on district by district over time," Augustine says. "They didn't do that. They had their own way they wanted to do that, and they did it their own way."

While Augustine was the chair of the commission, the commissioners were the only ones who could truly make decisions, she says.

Augustine proposed a good faith agreement, literally titled "Good Faith Agreement" — asking the commissioners to "work with the Commission Chair and sincerely attempt to resolve potential disputes" and not selectively leak plans to outside stakeholder groups before sharing it with the rest of the public.

Augustine has been a professional mediator for nearly two decades. She's an expert at trying to resolve conflict. But she wasn't actually a part of the commission's detailed negotiations.

"The way in which they conduct negotiations, I wasn't a part of it," Augustine says. "They didn't want help to frame their negotiation."

But as the commissioners battled it out behind closed doors on the final night, she was largely left in the dark.

"I saw the final plan when it was posted on the website with the rest of the public," Augustine says. "I didn't see it before that."

The commission officially met for over five hours on Monday night. But the public saw less than 40 minutes of it, and little of that was particularly informative. When the commissioners finally voted to support their plan, observers had no idea what was being voting on, a likely violation of Washington's Open Government Act.

At a press conference Thursday, the redistricting commissioners expressed regret across the board.

Graves says the commissioners had been meeting privately in two-person teams to hammer out the results of each map Monday night and were on a roll.

"We had the potential to reach agreement on these maps, which is a very important thing to me," he says. "I chose to keep working toward a deal."

He was working on the legislative district map behind closed doors with his Democratic House counterpart, April Sims, and had a plan to present it publicly to the rest of the commission at 7 pm.

But there was nothing that required that those kinds of negotiations be done behind closed doors — in fact, the purpose of the Open Public Meetings Act is to ensure that public commissions' "deliberations be conducted openly."

If the public could have seen whether, say, the Democrats were dragging their feet on the negotiations or the Republicans were being unreasonable about which district was going to straddle the Cascades, it wouldn't have just left them better informed — it may have encouraged the commissioners to negotiate faster.

9. Technical difficulties were experienced.

Today, that statement feels particularly ironic.

With minutes to go before midnight on Monday night, Fain lost his Zoom connection. But that was hardly the only technical snafu.

Dave's Redistricting App is an incredibly simple and responsive tool for quickly editing districts, developed by a programmer from Washington. But while the commissioners used that tool for drawing some of their rough drafts, they were stuck using a clunkier and more expensive software system called "Autobound Edge."

"You had many staffers doing big downloads and uploads on one hotel Wi-Fi system," says Nixon, the commission's communications director. "Hotel Wi-Fi is spotty and not great."

Technical issues are exactly why it's best to not wait until the last minute to agree upon a final map.

"I don't think I'm stepping too far out on a limb by saying that this work should not have been done at that stage of the process or that late hour," says Fain, "because it just increases the likelihood you're going to face those kinds of problems."

When Spokane County's redistricting committee was drawing up new county commissioner districts, they signed off on the final maps the day before the final deadline, giving their contractor time to officially finalize the map and deal with any lingering details.

And that was the intent of the Washington State Redistricting Commission as well: The staff knew that the final map should have been agreed upon days before the deadline.

"We had an earlier deadline set, but there was no progress by the point of that deadline," says Nixon. "The plan was to have it done on the 12th."

Asked if there was a certain point where she was alarmed that a final draft wasn't ready, Augustine responded, "Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha, ohhhhhhh," noting she frequently raised concerns that time was running out.

But three of the four commissioners came from the state Legislature, Nixon notes, where it's common for, say, the state's budget to be finished at only the very last moment. But he says legislators often have an incentive not to finish too early: They don't want to be bugged by lobbyists.

11. The "final" map may not actually be legal either.

If you look at the 2020 voting-age population makeup of the proposed District 15 in Yakima, it looks like over two-thirds of the district is Hispanic. But the 2019 data for the percent of citizens in the district who are Hispanic is much lower — only 50.02 percent.

Of course, all those arguments could soon be made irrelevant. With the deadline missed by the commission, it will be up to Washington state's progressive Supreme Court to draw the actual final map — and they don't have to stick to the boundaries agreed upon by the commission.

Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig, D-Spokane, is counting on it.

And if the Supreme Court screws up? Then, presumably, it's up to the federal courts.

*This piece has been updated to clarify the lack of support for the proposed "Good Faith Agreement."