Historic and virtually untouched, a 1,060-acre stretch of land north of Saint George's School may go unnoticed.

But past the worn-down barns and expansive fields lies densely wooded trails, rocky outcroppings and cliffs overlooking Spokane. There's also an approximately 2-mile stretch of the Little Spokane River with unique hydrogeological conditions perfect for sustaining salmon. For decades, Glen Tana farm, as the land is called, has been sought after by both conservationists and developers.

In August, it was purchased by the Inland Northwest Land Conservancy — a local nonprofit dedicated to conserving land, and improving and restoring waterways and habitats — with plans to sell the acreage to Washington State Parks and the Spokane Tribe of Indians.

"I think it's impossible to overstate the threat to this place," says Carol Corbin, the conservancy's director of philanthropy and communications. "When you go there and you see it, and you see the river, and you see the deer browsing in the meadow, and you see the ridgeline up against the sky, it's obvious that it's just a really important place to have protected in the long term."

Until the conservancy bought the land this August, it was owned by a family trust created by the late Charlotte S. Witherspoon, which entrusted the acreage to her five children with the requirement that any decision regarding selling the property be unanimous.

In 2008, three of the Witherspoons — William, Grant and James — were interested in developing the property for housing and wanted to prepare it for subdivision, sparking legal battles with the other siblings, Peter and Tannis, who opposed developing the land.

Yet an agreement was reached, with the five siblings opting to sell the property to the Land Conservancy for its $11.1 million market value.

"This piece of land has been one that our organization has been looking at for over 20 years," Corbin says. "Its adjacency to the urban core, the fact that it sits right on the line of the urban growth area of Spokane, puts it under tremendous threat for development. ... Our hope for years has been that we would be able to protect it from development and to hopefully open it to access and enjoyment by the community."

The property was purchased by Thomas Griffith when he moved to Spokane from Canada in 1888 and established Glen Tana farm, which was "renowned across the entire country for its modern dairy practices and sanitary features," according to a 2016 report from the state Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation.

On the farm, the family opened a tea room in their home. Griffith also bred and raised border collies that won medals at competitions across the country, and he was the first president of the Spokane Kennel Club.

At one point, the property spanned over 2,380 acres. Some parcels were sold and now are home to Saint George's School and the Spokane Fish Hatchery.

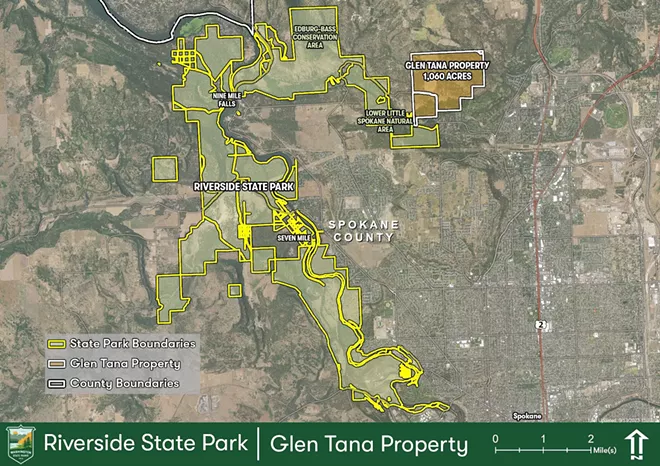

Glen Tana's location connects both Riverside State Park and the Land Conservancy's Waikiki Springs Nature Preserve, as well as some adjacent Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife lands.

Lara Gricar, the Inland Northwest region manager for the state parks department, says only 9% of Spokane County is permanently protected public lands, compared with King County's 51% or Yakima County's 36%, making this acquisition even more important.

"I also think — with the proximity to the city and within the county and to so many different neighborhoods as well as to an existing transit line — it may be serving some people that aren't able to get out into different parts of Riverside right now," Gricar says.

Washington State Parks currently is gathering public comment on adding the property to Riverside State Park, and developing a management plan for the property with the Spokane Tribe and the Land Conservancy.

"The idea is that we are bridge owners of that land, and then [the state parks and Spokane Tribe] will purchase the land from us and start to manage it for public access, likely around 2027," Corbin says.

TRIBAL HISTORY

The Glen Tana property lies directly within the approximate 3 millions acres of the Spokane Tribe's ancestral lands.

Warren Seyler, a tribal member working for the Department of Natural Resources who develops presentations and curriculum about the Spokane Tribe's history, says that the Little Spokane River once was home to a massive fishery.

"Right at that fork of the Spokane and the Little Spokane river, that was a major living area for the Spokane Tribe, mostly because of the fishery," he says. "There was just an abundance of fish that came there, not just steelhead but other species of salmon and other resident fish."

Several miles west of Glen Tana, the Spokane and Little Spokane rivers converge, creating an economic hub marked in part by the fur trading post the Spokane House, established in 1810.

Even before Spokane House, Seyler says that site served as a major living and trading location for the Spokane Tribe and other tribes in the region.

"All up and down the Little Spokane, you would have had living areas of Spokane tribal people from the Spokane River all the way up to the foothills of Mount Spokane," he says.

Seyler adds that Indigenous people have lived by the Spokane and Little Spokane rivers, and on the Spokane Tribe's ancestral lands, for upwards of 16,000 years.

"That's part of what it represents, is getting land back that represents the river people and all of our history that goes with that," he says. "It's almost hard to put into words because the value is so tremendous."

PROTECTING THE RIVER

The roaring river bashing the sides of enormous rocks. Trails lined by dense forest, 200,000 feet of shoreline. And 135 miles of hiking, horseback riding and access to the Centennial Trail.

Welcome to Riverside State Park.

Made up of around 11,000 acres of land, Riverside is Washington's second-largest state park. It was established in 1933 when the Civilian Conservation Corps and Aubrey White worked together to protect land along the Spokane River.

"[White] had a vision that Spokane as it developed would not repeat the mistakes that a lot of the Eastern cities had done and allow urban sprawl to occur without any regard for preserving public lands, especially public recreational lands," says Paul Neddo, Riverside's ranger.

White began buying land along the Spokane River after realizing how popular the modern-day Bowl and Pitcher area was among local residents.

Throughout the years, state parks has added various parcels of land to the park, surrounding sections of the Spokane and the Little Spokane rivers.

"There's always been an interest in preserving as much of the river as we can and working with the tribe, so that's one of the neat things I see happening with the Glen Tana is the partnership with Parks and Spokane Tribe with their fish hatchery," says Neddo. "That would connect directly with and expand the natural area land which still allows recreation, but it also serves as a wildlife corridor right here next to the urban area."

SALMON REINTRODUCTION

Until August 2021, 111 years had passed since salmon last swam in the Little Spokane River.

"Salmon was a way of life," says Monica Tonasket, secretary of the Spokane Tribal Business Council. "And once there was the elimination of salmon, a certain way of life went away."

Reintroducing the keystone species into the waterways was a primary reason the tribe worked with the Land Conservancy and state parks on acquiring the property, says Brent Nichols, director of the Spokane Tribe of Indians' Fisheries and Water Resources.

The unique hydrogeology of the Little Spokane River on the Glen Tana property made it a crucial location to conserve for those efforts.

The Spokane Tribe hopes to create an Indigenous Outreach Center at Glen Tana, documenting the tribe's history of living by the Little Spokane River, how the construction of the dams affected the salmon, and today's work to reintroduce the species to the waterways across the state.

Nichols says the Spokane Tribe and the Land Conservancy collaborated in 2020 to acquire Waikiki Springs Nature Preserve and release salmon into those waterways. It was a pivotal step in their partnership and in proving that salmon could survive again in the Little Spokane River.

"In this particular stretch right here from Waikiki Springs Trailhead down, you have a lot of influx from the aquifer water, and it's cold water," he says. "Even during the hot months, like last year in August when it was 100 degrees, the water here was still in the upper 50s, which is very survivable for salmon and trout."

He adds that another key to successfully restoring salmon populations in the river is restoring the habitat, not only at Glen Tana but within the entirety of Spokane's watershed.

The Spokane Tribe plans to begin working with the Spokane Conservation District on projects to reverse damage caused by farming and development along nearby stretches of the river.

"Some of those will be shoreline plantings, so creating shade and getting those back along the banks, snags in the water so that the fish have a place to hide," says Nichols.

The Little Spokane River faces a unique set of threats due to water rights laws that are different from those of most other nearby rivers.

"The river is unique in that property owners adjacent to the river actually own the riverbed itself," says the conservancy's Corbin. "People who own property along the main Spokane River, they own to the high water line and then the river is public domain, basically. But with the Little Spokane River, because it's considered non-navigable, the property owners can kind of do whatever they want on their section of river."

As a result, the Spokane Tribe has to work with property owners on projects like reconnecting and restoring the original stream beds to make them suitable for salmon and other native fish species.

"Reintroduction is not going to work without partnerships," Nichols says. "Being able to create areas like this that are preserved and can be utilized for those purposes is going to be very important as we move into the future."

NEXT STEPS

While the Glen Tana property is under ownership by the Land Conservancy, Washington State Parks just began its Classification and Management Plan, which develops park boundaries and management plans.

The process requires multiple rounds of public input and comment, which began in September and are set to continue through late summer of 2024, when the plan will be presented to the Washington State Parks Commission for approval.

If approved by the commissioners, the Glen Tana property will become part of Riverside State Park, and state parks will begin applying for grant funding along with the Spokane Tribe so they can both fully purchase the land from the Land Conservancy.

And while the conservancy received $6.6 million from grants, state appropriations and donations, the group took out a loan to cover the remaining $4.5 million used to buy the property.

"The collaboration between the Spokane Tribe, INLC and the Washington State Parks Department has been just really great," says Tonasket. "We don't always get that between agencies or entities, and it seems that as tribes, we're used to fighting for things. In this case, it hasn't been like that.

"We're working toward a common goal, and the work that we're all doing isn't just for the benefit of the Spokane Tribe, it's for the benefit of the region." ♦