This week, we have a cover story on how a rental emergency — delayed, obscured and possibly exacerbated by the state's eviction moratorium — is about ready to hit Washington state hard.

Some parts of Spokane are likely to be hit harder than others. Our story has a few anecdotes from West Central, a low-income neighborhood struggling with the effects of gentrification and a collapsing rental market.

But other regions are struggling just as much. The Zone, a neighborhood nonprofit stationed in the Northeast Community center, sent out a text survey to parents of school-age children attending Shaw and Garry, two middle schools in the Hillyard region of Spokane.

While it wasn't a scientifically weighted poll, the results were striking: Nearly a quarter said they were behind on their rent or their mortgage, and 74 percent said they were at least somewhat worried about losing their housing. They weren't behind by just a small amount either — the average respondent said they were behind on their rent by $2,000.

"One respondent, who was caught up in rent, commented at the end that she was frustrated," says Jene Ray, associate director for The Zone. "Her [family] had chosen to pay rent, but that didn’t mean they weren't behind on other bills and utilities."

The survey was focused on rent and mortgages, she says, but many of the respondents commented that they needed help with their utility bills.

In Washington state, there's a moratorium on water and electric shutoffs, but it's scheduled to end July 31. In the meantime, the City of Spokane and Avista are watching unpaid bills soar.

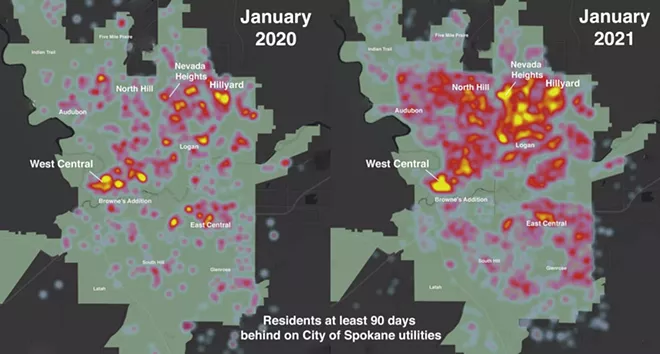

And when the City of Spokane crunched the data of residents who were behind by at least 90 days in their utility payments into a heat map, they saw one area was being hit in particular.

The West Central neighborhood, for example, was already struggling with utility payments before the pandemic. The pandemic made it worse, taking an existing hot spot and amping up the heat until the entire neighborhood had a bright molten glow.

But the real shocker is what's been happening further north: Sure, there were pockets of people behind on their utility bills before. But now the entire region is awash in utility debt.

Just as interesting is to see what's happened — or rather, hasn't happened — north of the river. We see some trouble in East Central, but comparatively, the problems are nonexistent. We always knew the South Hill was rich, but this shows just how little poverty there is.

The numbers back that up. While the city doesn't have the location for all the unpaid utility bills, at least $590,000 worth in the south Spokane council district represented by Betsy Wilkerson and Lori Kinnear. The northwest Spokane district, represented by Candace Mumm and Karen Stratton, had at least $960,000 in unpaid utility bills.

But over $1.2 million of the utility debt comes from Cathcart's district, more than double the amount from Kinnear's district.

Kinnear agrees that the vast difference in poverty rates between the regions in the city is a huge issue, but not an easy one to solve.

Not every renter, of course, directly pays for water, sewer or garbage. Often, that's paid for by their landlord. But most tenants do pay their electric bills. And Avista has seen a big increase in unpaid bills as well.

The number of Avista customers in the Spokane County behind on their electric bills has gone up 9 percent, says Shawn Bonfield, Avista's manager for regulatory policy. But it's the amount of money owed that's really shot up wildly.

Avista went from having $3.7 million owed to them in unpaid electric bills at the end of 2019 to nearly $8 million at the end of 2021.

He says that the problem is particularly pronounced in north Spokane ZIP codes like 99205 and 99207. And many of the folks who are behind have had difficulty with their utilities before.

It's difficult to separate, however, how much of the increase in unpaid bills comes from the soaring unemployment rates and other pressures of COVID, and how much of it comes from the fact that the moratorium has banned service shut-offs.

In Avista's case, Bonfield says that even as the amount of money owed has spiked, the number of people arranging a payment plan or get help from Avista has decreased by 35 percent.

Bonfield says he doesn't think so. He points to Idaho, which had a brief moratorium on utility shut-offs but which resumed normal operations last July.

"We've seen very few customers actually disconnected in Idaho," Bonfield says. "Disconnection again is always the last resort; we want to work with our customers to prevent that from happening."

Still, he says that that, as of right now, after July 31, Washington state customers who are behind on their bills and don't respond to Avista's notices to get help or establish a payment plan could risk disconnection.

In the case of city utilities, Feist says that the decision on how to handle shut-offs after the moratorium has lifted hasn't been finalized.

But as the pandemic wore on, Feist says the comparatively modest UHelp program paled in comparison to the actual need.