It's about noon, late May 2022, and 27-year-old Seamus Galligan is climbing out of a broken window of Spokane's Something Else Deli on Second Avenue, his backpack filled with hundreds of dollars of liquor.

A guy walking a dog spots him and calls the cops.

Seamus is arrested and, from the back of the patrol car, he looks out the window. And there, across the street — absurdly, impossibly — is his dad. The guy's wearing a Voterly T-shirt, the name of the app his dad's company developed. It doesn't make sense. His dad lives in San Diego, 1,300 miles away. They haven't talked in months, back when he'd promised, once again, that he'd try to get clean.

For a moment, he thinks he could yell loud enough for his dad to hear. But through the tinted windows of the squad car, he knows his dad wouldn't be able to see him. And then his chance is gone, and the paths of the father and son diverge once more.

There are more than 2,000 homeless people living in Spokane. But Ryan Cook — Seamus' dad, a tech executive — had flown in trying to find just one, his firstborn son, by the only means he knew: walking the endless streets of Spokane, talking to the many people who live on them.

Nearly a year passed — a year of false hopes and false starts, of jail stints and drug overdoses, broken windows and broken promises, near misses and near-death experiences, of crushing disappointment and impossible fortune — as Cook searched for his missing son.

And Cook carried with him the same question: Is my son still alive?

SPRING OVERTURE

In a sense — a philosophical but profoundly real sense — Seamus had once rescued his dad from homelessness.

When Cook was 16 and 17, he was living on and off the streets of San Diego. At 18, he learned that he was going to have a child. That prospect — being a dad, forging a future for his son — became that shit-just-got-real, everything-is-different-now moment.

So he got serious. He took up work at a shipyard. He started teaching himself computer programming. His son, Seamus Rune Galligan, was born in January 1995.

Twenty-eight years later, Cook is now the CEO of a tech startup called Vidaloop, which developed a voter information app called Voterly. But his son had become homeless, and now it was Cook's turn to rescue him.

By May 2022, the search had almost become a ritual, almost daily: Cook Googles "Seamus Spokane" or "Seamus Galligan Spokane."

His care package — trail mix, a new phone, pictures of their family — sent to Union Gospel Mission, where Seamus had said he planned to check himself in for drug treatment, is returned to sender. Seamus promised he'd call, but the phone hasn't rung in weeks.

And so Cook keeps Googling, keeps scrolling past the posts with the guitar player with the same name — keeps looking for even a single mention.

Desperate to find his son's name. Dreading to find his son's name.

"I'm worried he's been killed or overdosed," Cook says. Multiple friends of his have died from heroin overdoses, and the stuff his son is dealing with on the streets these days, fentanyl, is a whole lot worse.

This is the purgatory that countless parents of unhoused and addicted people are trapped in: desperately wanting to help their children, but not knowing how.

But Cook's wife has an idea. "Go find your son. I''ll take care of things here," she tells him. "We can handle it. Just do it."

Cook's plane lands in Spokane on the afternoon of May 27, 2022, and he sets up in a room in the downtown Best Western. He gives himself three days to find his son. He'd researched homeless shelters online. He remembers the places Seamus talked about, like House of Charity.

"My plan was just to talk to every homeless person and go in the shelters," Cook says.

But first, he grabs dinner at Iron Goat Brewing, where Galligan used to work. The manager can relate to Cook's pain — her own son ran away just two weeks after his 14th birthday, but the despair still lingers. She connects him with a guy named Kyle, who says he's definitely seen Seamus around, dragging a rolling suitcase behind him.

"Definitely homeless," Kyle says to him. "Definitely on drugs."

Cook rented a car but quickly realizes that he needs to be on foot. He needs to duck down alleys. He needs to see the people who are so easily ignored from the confines of a car.

He checks Browne's Addition, the staircase to Peaceful Valley, and around Grocery Outlet. He stops by the Cannon Shelter. He talks to a tall deaf man, whose friend translates Cook's questions into sign-language. Some of the places he visits make Spokane look like a "shithole," Cook says, but the homeless people are kind and helpful.

"They really liked my cause," Cook says. "It was almost like they wished someone was looking for them."

As night falls, he ducks into the liquor store on Sunset Boulevard. Nearby, a crowd of young homeless people, some of them armed with knives, dismiss his questions. But an older man behind him overhears.

"I know Seamus," the man tells him. "I can get ahold of him. I have to know he wants to be found first."

Cook hands him his business card.

The next day, Cook parks at the Spokane Valley Walmart and begins walking. He carries a sheaf of one-dollar bills. When he sees someone with a panhandling sign, he gives them a dollar and asks them a question. That gets him a new lead: Someone thinks that Seamus is at Camp Hope — a homeless encampment in the East Central neighborhood that, at the time, had grown to about 450 campers, the largest in the state.

So he walks toward Camp Hope.

THE LOST AND THE WANDERERS

Cook is not the first person to come to Camp Hope searching for a child.

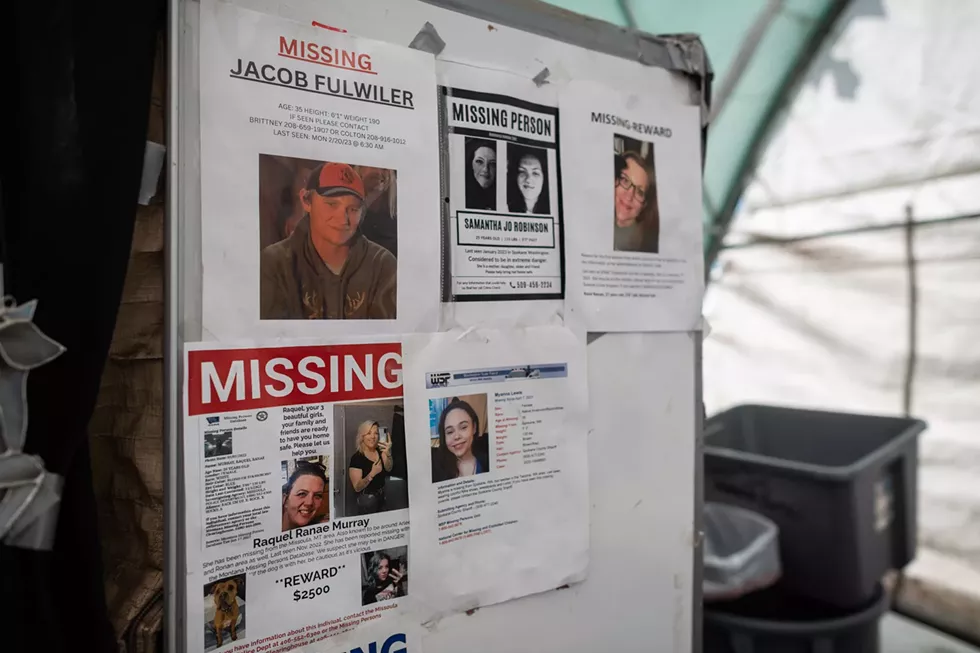

Even today, as Camp Hope has dwindled in size, there's a bulletin board inside one of the tents — a collage of pictures of smiling relatives, appended with "MISSING" and "please call." There's Danny. Samantha. Hazel.

"Raquel, your three beautiful girls, your family and friends are ready to have you home safe," one reads. "Please let us help you."

The missing person reports are full of homeless people who've wandered through their camp.

"Tons of people are looking for their children, their aunts, their uncles, their parents," says Julie Garcia, co-founder of Jewels Helping Hands, the nonprofit that has helped manage Camp Hope.

"I'm sure every person in that camp, every person downtown — they have somebody who loves them, somebody who remembers who they used to be and are still searching for that person," Garcia says.

But there's not a shelter in town, Garcia says, that will even confirm if your family member is there.

"We can't even do that at Camp Hope, which really sucks," Garcia says. "We don't know their story. We don't know what they're running from."

These relationships are complicated — they can involve substance abuse, domestic violence, bigotry and custody disputes. Sometimes they don't want to be found. But she does pass along the message.

Even if they don't want to return home, even if they don't want to get clean, she pleads with them to call their parents anyway. Because sometimes, when she's helping a woman who's addicted or who had her children taken away, she sees her own daughter.

This is Garcia's origin story. It's the reason why the controversial homeless activist has been willing to piss so many people off, burn so many bridges, fight for what she believes in.

A long time ago, she says, her daughter "met a boy" and "met meth" and that was it. She says her daughter was in and out of homelessness for years, though she's housed today.

"I went from drug house to drug house. I dragged her home and tried to force her into treatment and tried to force her to stay," Garcia says.

Garcia blames herself for contributing to her daughter's trauma and knows there's little hope of reconciliation today. (Her daughter says she's been clean for years.)

Experts caution against conflating homelessness and addiction — housing costs remain a much stronger predictor of a community's homelessness rate than overdose rates. But for many individuals, the two are inextricably linked.

"We have patients here who have space available in the most beautiful housing, the most expensive housing in the world," says Keith Humphreys, a psychiatry professor who co-leads the Stanford Network on Addiction Policy.

But first they have to give up using fentanyl, and they're not willing to do that. And their parents share in that suffering.

"It's the fellowship of those who sit home alone at midnight, hoping the phone will ring and also being terrified that it will," Humphreys says. "Will it be him saying I want to be home? Or will it be the police saying, 'We found your child.'"

EXIT STRATEGY

Seamus isn't at Camp Hope.

The young man has interacted plenty with the informal Camp Hope economy, which includes dealers and stolen property, but he hasn't been inside the camp itself in a while. Instead, at the very moment his dad is walking the streets of Spokane, he's being arrested.

Seamus tries to call his dad from the Spokane County Jail — Are you in Spokane? — but the call won't go through. On the outside, Cook repeatedly tries to punch in his credit card number to accept the collect call, to no avail.

Now, at least, he knows where his son is. He stays in Spokane. Two days later, he learns that his son will be released that day, but no one will tell him exactly when. So he waits for more than four hours, standing under the eaves near the juvenile corrections facility. The rain pours, night approaches, and he waits, watching other offenders trickle out of the jail across the street.

When Seamus exits, his dad is waiting for him. They talk for a long time, and Seamus wants to come home but can't because he doesn't have ID. And Cook's daughter, Seamus' half-sister, is graduating from high school the next day. So they work out a plan — Cook will pay for a hotel in Spokane until Seamus can find an apartment and get treatment. They'll stay in touch.

It was a mistake. Seamus is kicked out of the hotel, and they quickly lose touch.

"My regret is I didn't just force him," Cook says. "I could have talked him into coming home in May."

Months pass. In November, Seamus goes into the same Walmart where his dad parked in May, and he steals a $99 hoverboard. Leaving out the emergency exit makes it a felony.

SOMEBODY YOU USED TO KNOW

"We want to say, 'We love them, they love us, love conquers all,'" Garcia says. "It doesn't conquer addiction."

Mary Jenkins, a donor relations director at the Washington State University Foundation, describes seeing her "perfect child" transformed by drugs. Her daughter's insecurity over childhood surgery scars — and the bullying she received — made her susceptible to being pulled into bad relationships, sucked into addiction.

Today, those scars have faded. But there are new scars, the kind acquired through years and years of meth use.

"Had I not been told that was my child, I would not have recognized her," Jenkins says. "I just wish that people could see past the ravaged person they see in the streets and just realize that's a human being."

Those scars that make her unrecognizable are inside, too.

Jenkins' daughter has been through rehab multiple times, but "as soon as she's out, she just can't stay away from it." Each failure compounds, making it harder to seek help. It creates this horrible cycle — they do awful stuff to get the drugs they need to forget the awful things they've done.

Bridget Cannon, vice president of shelters and crisis intervention at Volunteers of America in Spokane, knows young people who walk right up to the front door of getting housing, and then just turn around.

"A lot of times they don't see themselves worthy enough," Cannon says. "They're saying, 'My fate is this because I'm not a worthy person."

They think the alleyway is all they deserve.

ALMOST SEAMUS

Seamus had come to the Inland Northwest, ironically, to turn his life around. He was using opioids and amphetamines, and his family got him into mental health care treatment, and on medication.

"He got his mind straight," Cook says.

Seamus moved to Coeur d'Alene, where his uncle lived. It was the chance for a fresh start, a chance to live independently. He thrived. He trained to become a bartender. He worked for a time at Crafted Tap House + Kitchen.

"He got a job, got a girlfriend, had a condo, had a cat — everything's good for a while," Cook says.

Sam Rowland, an Army veteran with his own rough past, remembers Seamus showing up to play bass in Rowland's band wearing a Compton hat and a tie-dyed shirt — looking very much like a California kid. But the kid was brilliant — Rowland could tell from the words he'd used — and crackled with passion.

"Miss that fire," Rowland says. "I wish the fire that he had was in every other person that I played with."

They called their band Almost Anything, Rowland says, as in "a bunch of people who never did much, but almost did something."

But success wasn't the point of it. It was music for music's sake, music as healing. It was powerful. But after he and his girlfriend had an ugly breakup, Seamus spiraled.

"Everything kind of fell apart," Rowland says, and Seamus fled to Vegas. "Maybe he got into some f—-ing trouble there. My last thought about him was, shit, I hope this kid figures it out."

It was 2020, a lot went wrong. The pandemic had devastated the restaurant industry. Seamus fell back into his heroin habit. He moved back to Spokane, seeking another fresh start. He found fentanyl instead.

But sometimes the deepest despair can lead to change. Rowland remembers 2017 in Reno, snow still on the ground. He was homeless. An alcoholic. Security spotted him trying to hide in the bushes outside of a casino and chased him away.

"I lost my ID that night," Rowland says. "I just literally had nothing. I had no way to help myself. All I had was my cellphone."

But that cellphone contained the only thing he needed. His dad's phone number.

"My parents never gave up on me. I always had an open door to come home to them," Rowland says. "It was my pride that continued to keep me away."

WINTER OVERTURE

The winter deepens, and Seamus is in trouble.

A week before Christmas 2022, he gets caught trespassing into Genesis Church, and the pastor presses charges. A few weeks later, he's camped out near House of Charity when he's busted under the new version of the city's anti-camping ordinance. He's booted from River Park Square twice in one day. He's repeatedly caught breaking into buildings — sometimes to sleep, sometimes to steal something.

As Cook flies back to Spokane on Jan. 31, he doesn't know any of this. He just knows he hasn't heard from his son in months. There's still snow on the ground when the plane lands.

"I didn't even have a return flight," Cook says. "I didn't know how long I was going to be there."

But almost immediately, he can feel the difference. The first time around, it felt like everyone he talked to was on his side, wanted to help him with his mission. This time, almost "no one I even talked to even knew him, had even heard of him."

"People seem angry. Hostile," Cook says. "Got a knife pulled on me."

A man he approaches downtown yells at him, a large dagger clutched in his hand. Cook jumps into the street, triggering a chorus of horns honking from downtown traffic.

If there was hostility from the homeless population, it was a kind of protective hostility, says Shaunti Cole, a homeless woman who considers herself the "mother hen" of the homeless community in central Spokane.

"It's cold. Everybody's dirty. Our stuff's wet," she says. "We've had a lot of our friends that have been killed. We still have a lot of people we don't know where they are."

On top of that, she says, there's the strain of having been "headline news" for the past year — and not in a good way.

Cook has been reading those same headlines, about the backlash to Camp Hope, about the tug-of-war between the state and the city over the issue. He's developed opinions as strong as any Spokane voter, including about the city's mayor and the former sheriff.

"I think their attitude is hostile towards the homeless," Cook says. "If you treat people without dignity, how do you expect them to get their dignity back and their humanity back and enter society again?"

As if to illustrate that hostility, Cook finds a homelessness resource guide, with a plan to hit up the free meals to look for his son, only to learn that the guide is riddled with errors.

"Almost all the places I went to were not actually giving out food at a time that it said," Cook says.

He wanders the frigid streets without results, his fitness tracker's GPS Etch A Sketch-ing his aimless spirals around Spokane, cataloging every fruitless step.

"When you're on these walks, all day, by yourself, looking for your son who might be dead... my whole life with him from the time he's born goes through my head," Cook says.

Jan. 31: 6,610 steps.

Seamus is a toddler. They spend the day together, dad pushing son in one of those trolleys that look like a tricycle.

Feb. 1: 20,123 steps.

Seamus turns 1, and he's already speaking in full sentences. He's in kindergarten and already reading chapter books. This kid is crazy smart. Prodigy smart, his dad thinks.

Feb. 2: 19,525 steps.

Seamus is 7 and at La Mesita Skate Park. He's pulling off weird skateboard tricks nobody has ever seen before. He's best friends with his dad. Maybe that was a mistake. Maybe your dad shouldn't be your best friend.

Feb. 3: 47,047 steps.

Seamus is in second grade and he's in trouble again, this time for drawing violent pictures. Dad's worried about his son's empathy. Years later his dad concludes that Seamus is probably on the autism spectrum, though he's never officially diagnosed.

Cook's getting nowhere. He's walking in circles. He surrenders and grabs a flight home, drowning under waves of regret.

Maybe he never should have praised his son so much for all the things that came naturally, instead of the stuff that was hard for him. Maybe he should have forced — or at least convinced — Seamus to come home last May.

This is the kind of second guessing, the kind of guilt, that is inevitable for parents in this situation.

"Kids who get struck by lightning, their parents still feel guilty," Humphreys says. "It's wired into us."

CHECKED OUT

Two weeks after Cook flies home, I'm in Spokane's Central Library, working on a story about the library's approach to homelessness, when I corner a trio of homeless patrons who are willing to talk.

"I'm Seamus. They call me Shamedawg," says one of them, a dude in his late 20s wearing a beanie and lugging around a roller suitcase. "I washed up in Spokane about a year and a half ago."

That's when he starts unspooling his whole story. He tells me about street kid days, about his breakup, his ill-fated trip to Vegas, about how his would-be entrepreneurial venture — a pill press to make ecstasy he bought with his stimulus check — got stolen. He tells me about how he wants to make a new start in Spokane, but that "homeless bullshit" keeps getting in the way.

He's blunt and open. He talks about the stealth video game style thrills of commercial burglary. He reviews various opioids.

"I f—-ing hate fentanyl... Fentanyl is garbage," he says. "I prefer heroin to fentanyl vastly."

Heroin has a nice warp to it, he says, and lingers for six to eight hours.

"Fentanyl skips all of that and goes straight to unconsciousness," he says.

Seamus refers to Camp Hope derisively as "Camp Dope Tent Shitty," and compares it to the Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong — packed slums that were demolished in the 1990s. He flashes his intellect, dropping words like "actualizing" during our conversation.

He breaks out in a brief debate about public drug use with Jeremy Root, another homeless library patron.

You wanna know, Seamus says, why homelessness is on the rise these days? Society.

"People just being like, I can't f—-ing take life in the corporate world, or life in the rat race," he says. "It's too farcical for me to pretend eight hours a day like it's not a f—-ing farce."

But as Seamus stands up to leave, that cynicism fades for a moment. He says he knows what he needs to do. Go back home with his dad. Get clean. Get his career started again.

Back in San Diego, Cook Googles his son's name again. There's a hit — my Inlander article about the library — and he's hit with a barrage of contradictory emotions.

It's anger: "Why aren't you calling your freakin' dad?"

It's happiness: He can still see Seamus' personality, in the rhythm and tenor of the quotes.

It's relief: His son is still alive.

THE LONG WAY HOME

The day the article on the library came out, Seamus lands in jail again — he's found trespassing in a Kaiser Permanente building. This time, thanks to missing his court date for the deli theft, he spends a month in jail.

But in its own way, it's a stroke of luck — it's an opportunity for his father to connect with him, to draft a new plan. When Seamus gets out on March 28, there's a Greyhound bus ticket waiting for him.

But it's all up to Seamus. He has to get on the bus and stay on the bus until it reaches San Diego.

The first part goes smoothly. Cook confirms his son got on the bus, and rode as far as Sacramento. But then weeks pass, and he doesn't hear from him.

He thinks Seamus might be somewhere in the Los Angeles area. There are over 18 million people in greater LA.

"There's no way I can go to LA and walk around intersections and yell his name," Cook says. "It was a ridiculous idea in Spokane."

All he can do is wait. Hold his breath. Hope.

ONE LAST FIREWORK

Seamus misses his connection. He's stuck in Orange County. But he doesn't want to call his dad and ask for help.

"People want to save face," Seamus says. "That's such a deep-rooted psychological need."

So instead, he thinks he'll prove that he has it all together — that he's in control — by making his own way back.

He makes it as far as Anaheim. It's dusk, a few hours before you can see the fireworks go off over Disneyland. He runs into a homeless woman at an encampment near Anaheim Plaza who asks for his help.

In the glow of the setting sun, he sees her fentanyl foils. He hates fentanyl. It's garbage. But he asks her for a hit anyway.

Why not just one last hit? Just to get it out of your system before you give it up for good.

Addict logic.

But he hasn't used the stuff in over a month. His tolerance is a lot lower. He makes the mistake of holding his breath. Blow it out, blow it out, the woman says, but —

A hospital bed. Anaheim Regional Medical Center. Seamus is vomiting, trying to breathe, choking on his own throwup. The nurses tell him he was taking just two breaths a minute. Seamus is booted out of his bed, and he's on the sidewalk outside, wearing a hospital gown and vomit-covered pants.

Coming so close to death doesn't change him, at least not yet. He returns to his old rhythms: Shoplifting from grocery stores. Dosing fentanyl a couple of times a day for weeks on end. Same shit, different streets.

This is, in part, why it's so difficult to break the fentanyl addiction, says Stanford's Humphreys, "how much of each day you spend getting high, being in withdrawal, thinking about fentanyl and hunting for more fentanyl."

And when Seamus gets a little sleep, after a few days pass when he isn't high, he begins to see. For him, it wasn't the fear of getting stabbed or overdosing that moved him. It was the slowly dawning realization that if he didn't escape homelessness and addiction now, he'd be stuck there forever.

"I had relevant things in my life that I didn't want to pass me by," Seamus says. "What am I doing?"

He walks into a T-Mobile store. He knows the number by heart. He makes the call.

END OF A LONG ROAD

"He called us to say, he just woke up and realized, 'I need help,'" Cook says. "The next thing you know, we're meeting with him at Old Town San Diego when he gets off the train."

He hugs his son at the train station, for the first time in a long time. There's not a big celebration — everyone is too exhausted, too hungry.

"It's good to be home," Seamus says. They're at Cook's house, and I'm talking to both of them over Zoom. "It's the end of a long road."

At times, it can feel like being back at square one. He's walking through his old neighborhood. He's spending time with his brothers and sisters. It's good, but it's sad — the relationships you make on the streets are by their very nature transitory, Seamus points out. You hope you never see them again — because they got clean or housed. But you miss them.

That leads to guilt, leaving people behind, Cook says of his son.

"I just keep telling him that he can't help them by being there with them," Cook says. "The way he helps them is to get out and he can dedicate his life to trying to help these people if he wants to."

It's dangerous out there. At the library, Seamus told me about a friend who got stabbed, nearly killed, in Mission Park.

"Lacerated his liver, punctured his lung, left him in the hospital for three weeks," he said.

A few weeks later, Root — the fellow homeless intellectual Seamus debated at the library — reported getting stabbed multiple times by five teenagers on the Monroe Street Bridge, which led to Mayor Nadine Woodward and Police Chief Craig Meidl saying that gangs of youths were "roaming in packs looking to prey on other people." Garcia calls them "predators."

Still, Seamus wants to come back to Spokane someday. But for now, he and his dad are planning a family vacation to Japan.

For all the confident opinions that people have about homelessness, those whose children have been through it are left with a kind of humility. They try everything: Carrots. Sticks. Tough love. Unconditional mercy. Until all they can do is simply wait for their son or daughter to say they want to get better. To finally return home.

Seamus knows it can be hard on them.

"It can take a lot of effort to hold out hope, against really dire circumstances and across years of misfortune and regret." Seamus says. "Hold out hope." ♦