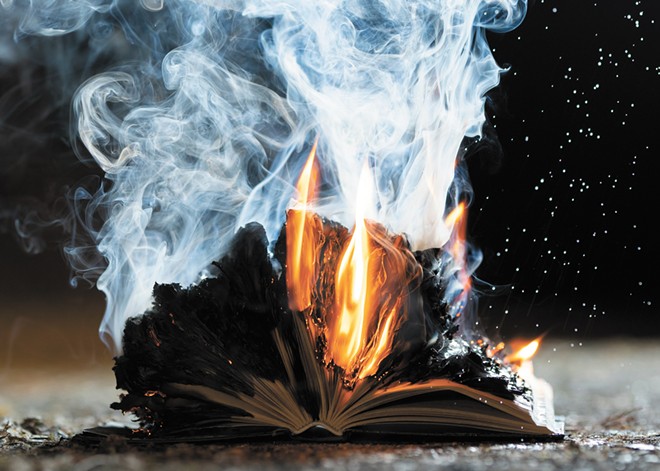

When I was 11 years old, I received a scandalous book. It was full of bizarre stories of monsters and demons and talking animals, terrible tales of violence and suffering, and complex meditations on morality and mortality. Also sex. Lots of sex.

You might have already guessed the punchline: The book was the Bible, an NIV with a blue vinyl cover. And while my approach to my faith's holy book has evolved, reading it and thinking about it remain an important part of my life. Even though — or maybe because — it is a strange and difficult book.

In my beloved Idaho and elsewhere, we're in an era of debate about which books should be available to children and teens in public spaces like city and school libraries.

Despite overwhelming public opposition, members of the Idaho Legislature keep introducing bills aimed at keeping minors from "obscene materials," sometimes so vaguely defined that it could boot the Bible out of libraries.

The status of the latest library bill will have changed by the time this column runs, so I won't dwell on individual legislation. Instead, I'll point to the Idaho Library Association's position that "library legislation is unnecessary."

This is a manufactured crisis — and it's meant to make you forget an important purpose of reading.

I want you to think back to the books you read as a kid. Try to remember one you loved, something you couldn't stop reading, even if you didn't normally love reading. A book you thought about long after you closed it. Maybe a book you still think about.

Did that book teach you a truth about the world? Was that truth, by any chance, strange or difficult?

For this column, I asked my friends to share the books that taught them something new when they were children. I received a flood of enthusiastic responses about books from different generations and genres, from the familiar to the obscure.

Books taught my friends about science, history and philosophy; friendship, family and love; grief, death, violence and war. They introduced them to people whose lives were different from theirs. They showed them that things they thought were weird about themselves were actually wonderful. They taught them they could stand up for their beliefs, maybe even save the world.

Books shine light on challenging ideas by encouraging us to examine and empathize with other people's stories.

tweet this

And yes, sometimes they were scandalous. Sexuality is part of life, so it shows up in stories. One of my friends jokingly calls novels like the infamous Clan of the Cave Bear "sex ed for nerds," and several titles my friends listed contain a few eye-opening scenes. (I remember an otherwise unmemorable Robin Hood retelling from my high school library for this exact reason.)

The flipside of this is that books with sex in them often tell critical stories about consent and assault: I was shocked at age 14 when I read Laurie Halse Anderson's frequently banned novel Speak, about a girl who is raped by a popular older student at a party. I also consider it one of the most important books I read at that age.

Books shine light on challenging ideas by encouraging us to examine and empathize with other people's stories. Keep in mind that empathizing doesn't mean imitating. One of the books my friends cited most was Gary Paulsen's classic Hatchet. I don't think any of them jumped at opportunities to barely survive in a hostile wilderness as teens, but Paulsen's story may have helped them survive a few metaphorical ones.

Kids in 2024 deserve to learn about all these parts of the world, and more. Some of today's books contain topics the books of my childhood didn't — but just because a story wasn't told before doesn't mean someone doesn't desperately need it to be.

When my sons were little, I read with them and used my parental judgment (not the Legislature's or anyone else's) to help them pick out books. Now that they're older, I trust them to make their own choices at the library, even if I cringe at my older son's love of horror and my younger son's insistence on re-reading his favorite dragon novels 17 times. I give them books I loved as a child, including ones that unsettled or challenged me (including my little blue Bible). I've taught them to consider what they're ready for, and I encourage them to talk to me anytime they have questions.

I want their reading to be unrestricted because I believe it needs to be.

I know they will encounter many things in this strange, difficult, beautiful world. So I let them encounter the world through books. ♦

Tara Roberts is a writer and educator who lives in Moscow with her husband and sons. Her new novel Wild and Distant Seas is available now. Follow her on Twitter @tarabethidaho.