"You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There's more of gravy than of grave about you."

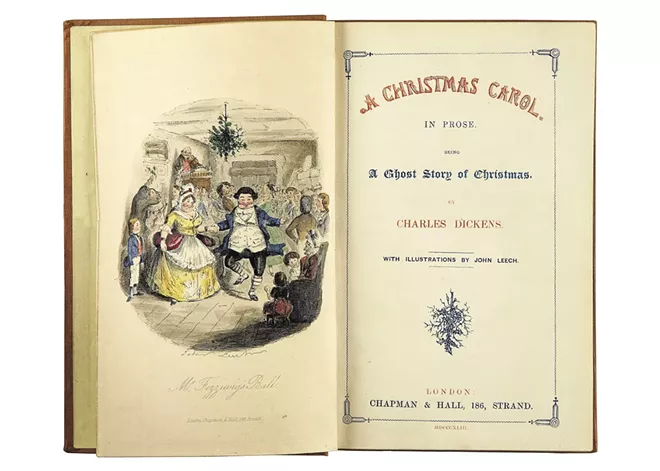

Thus in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol (1843) did Ebenezer Scrooge dismiss his dead business partner Jacob Marley's apparition. Marley's ghost is shackled eternally to "the chains I forged in life" for his avarice, cold, isolated existence, and contempt for humanity. Marley's tormented soul, Scrooge's doppelgänger, wanders in perpetual darkness. Like Scrooge, his "sole friend, sole mourner," Marley is a bitter, lonely man. While Scrooge's demeanor is repugnant, he should also evoke empathy because as a child he was neglected by his father — a "poor, forgotten self."

Marley's ghost exhorts Scrooge to seek redemption through the intervention of three Spirits who, like Virgil to Dante, compel him to confront the reality of his sins and guide him to salvation. A contemporary Parliament member declared that the book was more edifying than "all the pulpits and confessionals in Christendom."

A Christmas Carol is a modern morality play about predatory capitalism's destitution of workers. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times," opens another of Dickens' classic works, A Tale of Two Cities.

Fezziwig, a prosperous businessman, shares his profits with his employees and personifies the generous gift-giving and joy of Christmas, the antithesis of Scrooge. Bob Cratchit, impoverished by Scrooge's miserly wage, nonetheless savors the season. Dickens' paradox is that Scrooge, who is rich, is poor in spirit, while Cratchit, who is poor, is rich in family, love and generosity.

Dickens offers only a glimpse of 19th century London squalor. The reality was grim. These were hard times. In 1840 on average 25 percent of children died before age 5. Life expectancy was 40. For the London poor like the Cratchit family, life was more tenuous.

The fog that permeates A Christmas Carol was exacerbated by the burning of coal, the source of London's heat. Dickens: "The sky was gloom, choked by a dingy mist, descending in a shower of sooty atoms." This smog worsened bronchitis and tuberculosis. It is possible Tiny Tim suffered from rickets caused by sun exposure privation and the resulting vitamin D deficiency. In 1952, the Great Smog (a weather inversion combined with coal smoke) killed 10,000 in London.

In 1840s London, human waste gurgled into 200,000 shoddily masoned cesspools oozing a putrefying bacterial stench and leaching into drinking water causing typhoid and cholera. In 1842 London, 16,000 died of typhoid. In 1848, 15,000 died of cholera.

This putrid effluence flowed into the River Thames, which became an open sewer. It was also the source of fishmongers' haddock and eel, ubiquitous in London's diet. The magazine Punch christened the Thames "The Big Stink." In 1850, a government official despaired: "A portion of the inhabitants of London are made to consume a portion of their own excrement and pay for the privilege." The costly flushing toilet, invented in 1861 by English plumber Thomas Crapper, did nothing to mitigate the filth. It did, however, make bourgeois defecation more genteel.

The Victorian middle class thought poverty was caused by moral defect, sloth and inebriation. In his book Self-Help (1859), Samuel Smiles admonished the poor: "No laws, however stringent, can make the idle industrious, the thriftless provident, or the drunken sober."

On Dickens' Christmas Eve, two "portly gentlemen" solicited Scrooge "to make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute." Scrooge retorts, "Are there no prisons?"

"Many would rather die," say the gentlemen. Scrooge is chillingly cantankerous: "Then they should do it and reduce the surplus population." (Here Dickens alludes to Thomas Malthus' 1798 "Essay on Population," in which Malthus prescribed "positive controls" on population: famine, disease, war.)

Poor Laws of Dickens' time relegated the chronically poor to workhouses run like prisons where the incarcerated were treated like criminals, enduring hard labor and discipline. Recall Oliver Twist. (In 1896, 7-year old Charlie Chaplin was sent to a workhouse.) For those unable to repay debts, there were debtors' prisons with inhumane conditions comparable to workhouses. Common criminals, beggars and prostitutes were often forsaken to insane asylums like London's hellish Bedlam. In the 1840s, as workhouses and debtors' prisons overflowed with Irish famine immigrants, 168,000 of these wretched poor were deported to Australia.

Dickens' England, having "lost" its American dominion, sought to sustain its nascent imperialism by subjugating India and China. The Chinese commodity most demanded by English consumers was tea. To satisfy this voracious domestic market, the British East India Company exchanged Indian opium for Chinese tea. Ten percent of Chinese became addicted to opium. Queen Victoria — whose German-born husband, Albert, bequeathed Christmas the tannenbaum — laced her tea with opium. Accounting firms such as Marley & Scrooge were beneficiaries of this illicit trade, as well as cotton imports from the America's Southern plantations for English mills and their appetite for child labor.

There are over 100 film adaptations of A Christmas Carol. I recommend the 1935 or 1951 British adaptations. (Georges Melies' 1900 four-minute Christmas Dream is enchanting. Melies, the father of film special effects, is a character featured in Martin Scorsese's Hugo of 2011.) Spokane's Civic Theatre is performing A Christmas Carol live on stage through Dec. 22.

Another Christmas film classic is It's a Wonderful Life (1946), which, like A Christmas Carol, is about a life-transforming epiphany realized through divine intervention. While Scrooge is an "old sinner" and It's A Wonderful Life's George Bailey scrupulously ethical, both are conveyed by spirits who guide them through revelation to redemption — and in Bailey's case, his angel saves his life.

This winter, avarice and wrath are again ascendent. It may seem as if the coming darkness will be implacable. Light one candle. See how it illuminates the darkest room. Scrooge and George Bailey can be that candle. And we are the light or the mirror that reflects it. ♦

John Hagney taught Spokane high school and college history for 45 years. He was a U.S. Presidential Scholar Distinguished Teacher. His oral history of Gorbachev's reforms has been translated into six languages.