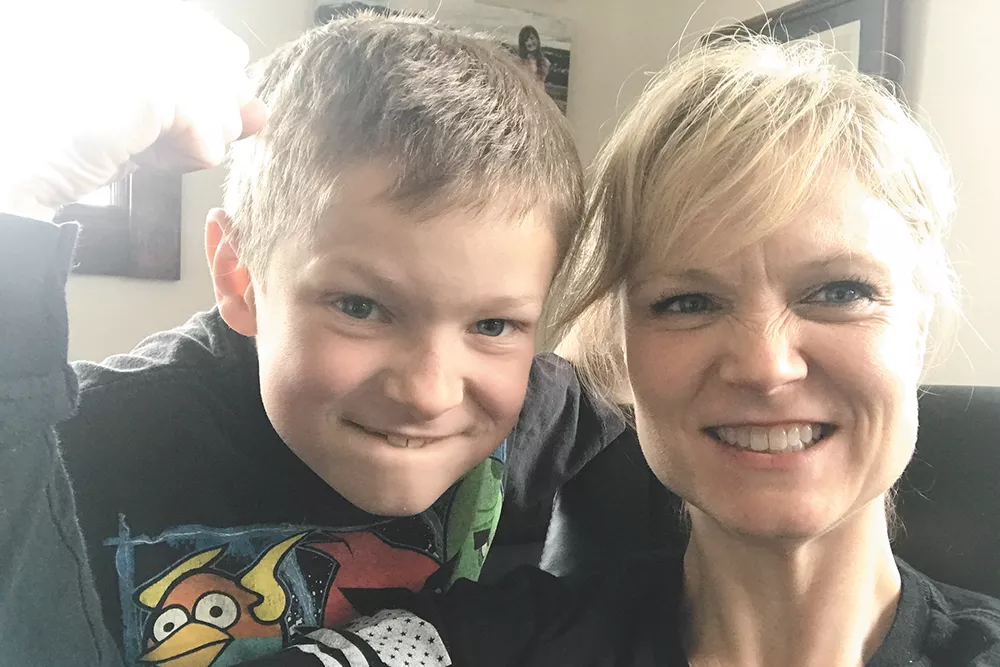

Nine-year-old Rowan says he loves going down "crazy-steep hills" on his sled and "making sounds on a hair-comb." As for what he hates? Spider bites. Hospitals at night. And, most recently, "getting shots with a [big] needle every two days."

Rowan was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes last March. His pancreas wasn't properly producing insulin, and so he'd need to get it artificially for the rest of his life.

His mom, Jacquelin Maycumber, recalls standing in the pharmacy at Sacred Heart Medical Center in Spokane, reeling with the cost of the devices and medicine he'd need — $1,000 initially, and then possibly hundreds of dollars every month for insulin for the rest of his life. Luckily, both she and her husband had insurance.

"I said, 'Thank you, God, for us being able to pay for this,'" she says.

But then the thought of all the parents who couldn't afford it hit her. Without insurance, Rowan's insulin would have been as high as $500 a month, Maycumber says. Effectively, kids are being held hostage, their parents told they have to shell out hundreds every month or their child dies. And the cost of the ransom keeps increasing: In only a decade, insulin's price tag has skyrocketed by 250 percent.

But unlike so many parents, Maycumber could actually do something about it. She's a Republican Washington state representative from deeply conservative northeast Washington. This year, she's rallied together a bipartisan group of legislators to cap the cost of insulin copays and figure out how to stop the price increases.

"Parents have contacted me — this is a 24-hour disease. This is a 3 am disease," Maycumber says. Her voice cracks over the phone. "I can't imagine the stress of either buying bread or keeping your kid alive."

Maycumber wasn't the only legislator who's been grappling with insulin's cost increase. Speaker of the House Laurie Jinkins, a west-side Democrat, recalls speaking at a camp for kids with diabetes last spring. A little girl raised her hand.

"I was expecting some off-the-wall question," Jinkins says. "She was 5. And she asks, 'Can you help my family with the cost to pay for my insulin? Because it's hard for my family to pay for my insulin.'"

Jinkins knows the struggle. She was diagnosed with diabetes when she was 12. She's been taking insulin for 43 years.

"Every job choice I've ever made since I became an adult has to do with having insurance coverage," Jinkins says. "I didn't look at how much they were going to pay me. I looked at whether I was going to have fair coverage."

But for others, it's not as easy. Young adults, Maycumber says, sometimes feel the need to scrimp on their insulin payments to save money. But cut back too much on your insulin, and it can damage your eyesight, your limbs, your kidneys and even kill you.

"I was just stopped yesterday in the hallway and a woman was crying," Maycumber says. "She almost lost her brother."

Maycumber says it wasn't difficult for her to get signatures for her bill — almost immediately, she had 30 co-sponsors.

The bill, which was heard in a House committee this week, mandates that all health insurance plans issued next year cap the out-of-pocket cost of insulin at $100 per month. But it also goes further than that: It establishes the Total Cost of Insulin Work Group, a team of representatives from state agencies — including the Attorney General's Office — and a variety of medical professionals. Their mission will be to figure out how to drive down the cost of insulin as quickly as possible.

It may seem odd for a conservative Republican to champion a bill capping prices, but Maycumber doesn't believe there's a contradiction between her bill and her support for capitalism.

After all, the American health care system isn't a free market, she says. It's a mess of bureaucracy and convoluted rules and obscured prices and hidden costs and backroom negotiations.

"When you talk about the free market, you don't have this over-regulation, nontransparent piece," Maycumber says.

Jinkins, meanwhile, has a one-word explanation for what's gone wrong.

"Greed," she says.

It's been 99 years since insulin was first developed as a drug. But as a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine article explains, in the years since pharmaceutical companies have repeatedly patented new versions of the drug — effectively preventing generic versions of the complicated drugs from being developed by their competition. And instead of the three manufacturers of insulin trying to undercut each other on price, they've all been hiking their drugs effectively at the same rate.

Meanwhile, pharmacy benefit managers — firms that were developed originally to help cut drug prices — further complicate matters. Instead of simply pushing for lower prices, endocrinologist Kasia Lipska writes in the New York Times, the pharmacy benefit managers are raking in what are effectively kickbacks from drug companies, contributing to as much as 50 percent of the list price of insulin.

It's a "black box," Jinkins says. "No one can really see what's happening."

But Maycumber hopes that her bill can pull the curtain back, and reveal the problems with what she considers a "government-run scarcity."

"We have to see why this is occurring. I think this is the most important part: We recognize that there's a problem. And now we're going to try to solve it," Maycumber says. "If I can help one person — all of the politics is worth it."

Rowan says that grappling with diabetes comes with a lot of challenges, beyond just the "poke, poke, poke, poke, shot, shot, shot, shot" rhythm of needles and pumps. As a fourth grader, it's a stressful thing to feel different.

"You're going to feel like a loser," he says. "You're going to feel like, 'Oh my gosh, nobody's going to like me because I have this weird disease.'"

But Rowan says he's learned that there's good that comes along with the bad. There's a whole community of people out there like him. Maycumber points to Jinkins as a role model for what's possible.

"When she became speaker, I sat my son down and said, 'You can do anything,'" Maycumber says. "I think that's really important for kids to see that success."

But even with his loving parents, both employed, both with health insurance — there's that lingering question in the back of Rowan's 9-year-old mind.

"Dude, what if we don't have enough money to buy this insulin for me? I'm going to die if that happens," Rowan says. "It's something that I worry about. Death is a big fear for me." ♦