Fifty-eight-year-old Tony Williams was coming apart. He was spending nights on a cot in a Seattle hospital while his 75-year-old mother battled cancer in May of 2018. Simultaneously, Williams was reliving the regular beatings and physical abuse he endured from her as a child. He also had auditory hallucinations stemming from his schizophrenia resurface.

"It just all came flooding back — the auditory hallucinations, the PTSD, the fear of being hit," he says.

Days before his mother finally succumbed to cancer, Williams wandered into a small park near the hospital to smoke a cigarette. Surrounded by hedges, the space was secluded and peaceful. He sat down on a bench and lit up when a stranger walked into the park and sat next to him. The man broke out a pipe and a small baggie of crack cocaine.

"You don't mind if I take a hit here, do you?" he asked, according to Williams' recollection.

"No, go ahead," Williams responded.

The stranger then offered to share: Do you want to take a hit?

Williams, who had been sober for over a decade at that point and was a professional drug counselor in Spokane, said "yes."

Then they got high together.

Relapsing on the park bench that day marked the beginning of Williams' unravelling as a well-respected drug counselor. Less than a year later, in April 2019, he was booked into the county jail on charges that he sold large quantities of methamphetamine and heroin in Spokane. He's now being held at Geiger Corrections Center on $100,000 bail while his case slowly plods through the courts.

News of his arrest and the allegations against him sent shock waves through the local addiction-recovery community, who knew Williams as an accomplished and exceptional counselor with lived experience that made him relatable to his clients.

"He was just kind of a rock. He was one of those people that everybody kind of gravitated to," says Sabrina Ryan-Helton, a current staffer for the Bail Project nonprofit and a recovering meth addict who met Williams roughly a decade ago. "There was no one who didn't like him and look up to him."

While Williams wouldn't comment on the pending charges against him — he maintains that while some allegations are true, "a lot of it's not" and that he never sold to clients — he agreed to sit down with the Inlander while incarcerated for a series of interviews.

He opened up about his ongoing struggle with addiction and his remarkable journey from selling and using drugs to becoming a well-educated addiction professional and then allegedly going back to the beginning, feeding the addictions of others. His story is also indicative of the brutal grip addiction holds on many people, and how it can still tear down even those who have years of sobriety behind them.

LIVING UNDER THE GUN

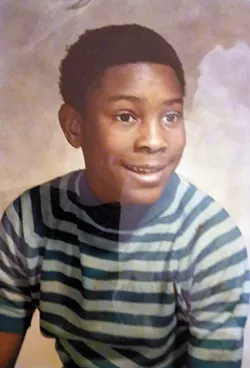

For Williams, much of his life was defined by his relationship with his mother — and the beatings she gave him as a child: "I was pretty angry. I was pretty good in sports. I was a pretty good fighter," he says. "I'm a product of being physically abused by my mom."

For Williams and his younger sister, Rita Green, their mother, DeCharlene, was a person of paradox. A descendant of slaves from Texas, she was known as a fearless, outspoken, hardworking and prominent member of Seattle's black community. She started her own successful beauty salon and boutique before going on to found the chamber of commerce for the Central District — Seattle's historically black neighborhood — in 1983 and pushed the black community to build political power and wealth to combat long-term institutional racism, primarily through buying and owning property. She unsuccessfully ran for mayor in 1993 and in news reports was described as a "pioneer" and a "trailblazer" in Seattle.

"She was one of the more forthright-speaking black community leaders that we ever produced," says Larry Gossett, a current King County Council member who was heavily involved in black student activism at the University of Washington during the late 1960s. "She wasn't scared of anybody."

Simultaneously, the single mother worked long hours, was rarely home and beat both her children on a regular basis.

"The whoopings we got, my mom would be in jail," says Green, 56, who recently worked as an account operations manager at a Seattle-based biopharmaceutical firm. "We got whooped with extension cords. We'd have marks all over us."

Tony got the worst of the beatings. He says his mother would frequently blame him for issues or get mad at him because he looked like his father, who was out of the family picture. Green also says that her brother was mischievous and would draw ire from their mother over things like making nunchucks from broom handles or not doing his chores.

"I got beat on a daily basis," Williams says. "I have whip marks on my back that will never go away."

His sister says that DeCharlene always viewed herself as a hard-working mother: "From how she grew up, to her she was a good mom because we had food, a roof over our heads, clothes. To her, she was doing a good job. In our eyes, she wasn't doing a good job."

"My mom helped a lot of people. But she didn't help her kids," Williams adds.

To cope, Williams says he channelled his anger into athletics at school. During high school he thrived in football and other sports. He also worked part-time jobs and took care of his sister at home when their mother wasn't around. But that didn't keep him entirely on the straight and narrow. He sold weed on the side, got into fights, hung out with extended family members who got into trouble, and ended up spending nights away from home with a group of teenage runaways or at his aunt's house, who suffered from a well-concealed heroin addiction. (Williams says he gave her money to buy heroin to keep her from going through painful withdrawals.)

Finally, one night, during his senior year of high school, Williams had enough. As he recalls it, his mother tried to beat him because she thought he started a fire in the house. But this time Williams was big enough to defend himself.

"I ended up grabbing her and shaking her and pinning her to the ground and saying, 'You're not whooping no more, you're not whooping me right now because I haven't done anything. I'm a man. I can take care of myself,'" Williams says.

He recalls his mother firing back: "OK, if you think you a man, go out there in the streets and take care of yourself."

"And that's what I did," he says.

After he graduated from high school, Tony spent the next two decades living an increasingly rough-and-tumble life on the streets of the greater Seattle area. He started selling harder drugs, developed an addiction to crack cocaine, fathered five children, was in and out of jail, and went to state prisons on three separate occasions for a variety of "drug-related" felony convictions, including second-degree robbery, records show.

He briefly attended Shoreline Community College, but it wasn't to last. As a symbolic permanent marker of the period, he garnered a scar from a bullet he took to the arm in his mid-20s when he and his friend were jumped on the street.

His sister says that the two of them largely fell out of contact during this period and that she would only hear from him when he was in jail asking to be bailed out or when he was attempting to start anew and get sober. Green also frequently stepped in to care for the kids when he wasn't around.

"You'd never hear from him when he was out on the street," Green says. "Then they get locked up and all of a sudden they want to call you.

"It was always drugs," she adds. "Always."

During his first stint in prison when he was in his early 30s, Williams was formally diagnosed with schizophrenia. He says he gravitated towards crack cocaine to not only keep him awake and alert while on the streets but also to try and suppress the auditory hallucinations he'd experience because of his mental illness.

"I used to feel more normal," he says. "That worked for a long time. And then, all of a sudden, it stopped working. And [then] it was about me chasing the drug more and more and more."

While long considered to be an issue of morality and personal willpower, drug and alcohol addiction is now considered by experts to be a health condition: The National Institute on Drug Abuse defines it as a brain disorder that is chronic, relapsing yet treatable — and "characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences."

For Williams, addiction is almost a supernatural force in his life: "They say the disease is cunning, baffling and powerful," he says.

ROAD TO RECOVERY

In the early 2000s, he was living in a combination of shelters and cheap hotel rooms with his girlfriend of about a year, Anna Marie Sullivan, a chronically homeless heroin addict who financed her drug use by "working the streets." Williams, meanwhile, sold drugs to feed his personal crack addiction.

"I was a hustler, she was a hustler. We always managed to get a hotel room, stuff like that," Williams says. "Sometimes, when we didn't want a hotel room, we'd save our money and sleep [at a shelter] so we'd have money in the morning to get high."

Sullivan, who had been homeless for years, had talked about how she had family out in Spokane County and that she wanted to move home to get clean. She had called her mom ahead of time to make arrangements to stay with her. At the time, Williams and Sullivan were at a homeless shelter in downtown Seattle.

"We wanted to get clean," Sullivan, 54, tells the Inlander during an interview in the Spokane County Jail. (She's currently booked for violating a no-contact order with Williams after she allegedly tried to run him off the road last summer in a car because she thought he was cheating on her with a prostitute, according to court records.) "We wanted to make it work so we came over here."

They hopped on a Greyhound bus to Spokane in 2002. Williams was in his early 40s at the time. They went to Spokane Addiction Recovery Centers to get clean together — Williams also got situated with an effective medication regimen for his schizophrenia — and started becoming active in local addiction-recovery groups. It was during this period that Williams started seriously considering the notion of becoming a drug counselor.

"Everyone I talked to — my sister, my cousin, friends in the program that I met in recovery — they all said, 'you'd be a good drug counselor,'" he says. "I [also] had to be realistic about the kind of work that I could do because of my criminal background.

"I had been in the program for a while. I was sponsoring people," Williams adds. "I saw how happy it made me feel to see people get off the drugs, doing responsible things."

So he enrolled at Spokane Falls Community College to get an associate degree and study chemical dependency. (Sullivan, his girlfriend, also went to SFCC to study social work, she says.) There, he thrived in the academic environment, former classmates recall.

"He did very well in school, was very dedicated, had a passion, and worked well with all the people in school," says Pamela Joe Lopez, a current drug counselor and former classmate of Williams while they were both studying chemical dependency. (She is recovering from meth addiction.) "He was just always an inspiration given all the mental health issues he had."

"He was a leader in pretty much all our classes," she adds. "He was professional and organized."

The period also marked a rekindling of his relationship with his mother, which had been all but dead to him during the years after he left the family home. He started calling her every Sunday and talking about his sobriety and his success in his studies. Williams says that while they never directly addressed the abuse — she also didn't apologize for it — his mother was proud to hear that he had turned a corner.

"I wanted to make my mom proud, I wanted to make me proud, and I just really wanted acknowledgement from my mom that she beat me unnecessarily," Williams says. "Realistically, she did the best she could at saying she was sorry. She just couldn't find herself saying it. She's a proud woman."

"They really were starting to get really close. I know she was very proud of him," Green says.

At his SFCC graduation ceremony in 2010, Williams remembers his mother making a complete scene from her seat in the bleachers at the venue.

"My mom was so happy. It was crazy," he recalls. "She had this big old hat and she was standing up. She would not sit down. And I'm down on the ball field, she's up in the stands [yelling] 'Tony! Tony!'"

"I'm like, 'Oh god,'" Williams adds. "My classmate was like, 'Is that for you?'"

From there, it seemed like the sky was the limit for Williams. His relationship with Sullivan was going strong, and he went on to get a bachelor's degree and then a master's degree from Whitworth University in social services and administrative leadership, respectively. He also got credentialed by the state to work as a licensed mental health counselor associate, and worked as a counselor at New Horizon Care Centers before moving to Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services in 2014, where he remained through January 2019.

He also became active in the community, holding barbecues at his house for members of the recovery community, speaking on panels at regional universities and assisting in the successful local "ban the box" campaign to prevent employers within city limits from asking about applicants' criminal histories before interviews. (He testified on the issue before the Spokane City Council in 2017.)

Blake Redding, executive director of Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services, says that Williams was a good employee who was well-liked.

"He came with great references. He came on as a trainee and worked his way up," he says. "He started out in withdrawal management as a chemical dependency professional and worked up to get his mental health license and then worked up to group therapy and case management."

Former clients and associates describe him as a dependable, likeable, relatable and empathetic counselor and general member of the broader recovery community.

Ryan-Helton, with the Bail Project, recalls meeting Williams at the Hoot Owl, a local recovery group, in 2009 when she was pregnant and trying to get clean from meth.

"He was a board member [of the group] and he worked at the coffee counter. He just was very encouraging and caring — but he also didn't take any crap. He'd tell you straight how it was," she recalls. "I walked in that club and met Tony while six-and-a-half months pregnant and 24 hours clean off of meth. There was no judgment. There was nothing but acceptance and love. And I needed that."

Angel Tomeo Sam, another staffer with the Bail Project and a former client of Williams when he was at Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services — she suffered from heroin addiction — says his familiarity with life on the streets was invaluable in his work as a counselor.

"His experience was really similar to mine, being formerly incarcerated, being gang affiliated in our past and really struggling with addiction," Tomeo Sam says. "He was really a champion for these guys in recovery who are men of color, have been gang affiliated, have been to prison, all of these men who have been in the same situation that he has and have been seeking recovery. I remember seeing him inviting guys over for the Super Bowl and different gatherings."

"It's nice to instill hope in people and then watch them actually do some things and go from this person who is very insecure, no confidence, nowhere they want to be, to be a person who is full of confidence," Williams says at Geiger Corrections Center. "That's what I loved about counseling."

THE DOWNFALL

After Williams' mother died, things started to fall apart. His relationship with Sullivan was deteriorating after cheating on her when he was in Seattle. He also says that he had trouble getting a medication adjustment for his schizophrenia over the course of the summer in 2018. In August, he relapsed again. Eventually, by December, Williams says he started living in motels.

Sullivan described Williams mental state after his mother died: "Angry. And just not himself. He just wasn't there. He wasn't coming home. He was a completely different person."

Then, in early December, the Spokane Police Department's Special Investigative Unit began organizing a sting operation on Williams after getting tipped off by a confidential informant that he was selling sizeable quantities of methamphetamine and heroin. They also set up surveillance on the Shangri-La Motel where Williams was staying, according to court records.

"That confidential informant was the person that identified that suspect as a person who was dealing large amounts of narcotics," Brad Arleth, captain of SPD's Special Investigative Unit, tells the Inlander. "That's how we got onto him for that investigation."

Using the same informant, SPD detectives conducted a series of controlled buys from Williams from early December through Jan. 24. During the first buy, Williams sold the informant quarter ounces of meth and heroin, followed by a second buy of a quarter pound of meth. Then, on Jan. 3, the informant used $3,200 in recorded currency given to him by the detectives to buy 10 ounces of meth while wearing an audio recording device. Williams allegedly complained to the informant about the difficulty of keeping up with his customers' demands and later griped that the informant's phone calls were interrupting his counseling job, per court records. During a buy on Jan. 9, Williams allegedly told the informant that he made over $2,000 in the previous hour.

"He was at least a mid-level dealer," Arleth says. "He was moving a substantial amount of drugs every week."

Then, on Jan. 24, SPD stopped Williams in his car with a signed search warrant. They found $2,441 in cash in his pant pockets and multiple ounces of both methamphetamine and heroin in the "center console" of his vehicle.

During a subsequent in-custody interview with detectives, Williams waived his constitutional rights and said that he had been "trading both methamphetamine and heroin for sex since approximately August 2018" and that he began selling narcotics for profit around October 2018, according to court records. Williams also said that he had nine regular customers and 12 infrequent buyers and had sold "quarter pounds of methamphetamine or more" on "several occasions," records state.

"He's supposed to be one of the good guys helping people," Arleth says. "That's the disgusting part."

Williams was initially released before getting arrested again in early April on a warrant. He's been in Geiger ever since, intent on taking his case to trial. While he won't comment on the specifics of the allegations, he maintains that the police and prosecutors are misrepresenting him: "I'm not a big drug dealer or nothing. I'm just not," Williams says.

When the news broke of his January arrest, he was subsequently fired from his position with Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services.

"He was great. He was very well-respected in the community. That made it even more disheartening when it happened," says Redding, Williams' former employer. "There's nothing great about it. A guy who worked so hard to get where he is and then one slip."

In the recovery community, his arrest hit hard those who had drawn inspiration and hope from Williams' story and his work in the community.

"They're kind of broken-hearted, just traumatized a little bit by it," Lopez, a former classmate of Williams and current drug counselor, says. "I think it hits them pretty hard."

At the same time, his friends and colleagues appreciate the nature of the issues that Williams was grappling with: "We're all that close to that relapse," Tomeo Sam says. "We're all that close to the end."

EYEING REDEMPTION

At Geiger Corrections Center — a drab military barracks near the Spokane airport that was converted into a jail in the 1990s — Williams sits behind a clear partition in one of the scuffed attorney booths donned in the yellow pants and shirts given to inmates. He's both upbeat and hopeful (he laughs exuberantly during humorous moments) and remorseful and somber. He acknowledges that he let down the community — especially the recovery community — and that he lost his way. In the background, the voice of a guard blasts over the facility's public address system, calling on certain inmates to come to the main office, "A Control," for various reasons.

"I know that I've disappointed a lot of people," he says over the din of watercooler talk among jail guards feet away. "The best thing I can do for me is to be honest and get the help I need."

A longtime friend of his has been visiting him at Geiger to run through the 12-step program with him, such as taking a "moral inventory," the fourth step of the process.

He also says that he is trying to organize a jailhouse wedding with his new girlfriend, Jennifer, and intends to start a sober house for couples financed with an inheritance from his mother once he gets out of jail. He says that many facilities don't allow couples to go through treatment programs together, pushing them away from seeking recovery altogether.

"I just know that I'm not going to give up and I'm going to work on myself and I'm going to get myself together," Williams says. "And I will do whatever I can to help the next person get themselves together if that's what they want. Period."

At times, his confident demeanor slips when discussing his prospects or the status of his case. He says he's been haggling with the county public defenders to get an attorney he deems adequate, struggling to get sufficient psychiatric medication while behind bars, and his trial isn't slated to occur until fall: "I worked hard. Screwed now, but I'll make it work out," he says.

Williams also says that he's run into former clients at Geiger. He says the interactions aren't awkward: If anything, they almost serve as a reinforcement of what he used to instill in former clients when he was a counselor about how recovery requires constant maintenance.

"I could relapse just as much as anyone else if I don't do what I need to do to take care of myself," he says. ♦

DEFINING THE CONDITION

Drug and alcohol addiction is widely considered by experts to be a chronic complex brain disorder caused by biological chemical dependency, as well as various environmental, personal, and social risk factors that can both help initiate drug use and reinforce physical addiction, such as personal trauma, mental illness and poverty. (Sustained drug use can also exacerbate or initiate the onset of mental illness, such as psychosis.)

On the biological side, addictive drugs are believed to effectively rewire the brain by disrupting its neurotransmission process, which works to regulate emotions and behavior. Parts of the brain that govern self-control, stress, and the positive reinforcement of healthy behavior — like eating and sex — are recalibrated to prioritize drug use to produce pleasure and stave off irritability and anxiety at the expense of rational decision-making, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. These biological changes can also remain long after an individual has stopped actively using, contributing to relapses.

LATEST IN TREATMENT

Increasingly, cutting-edge drug and alcohol addiction treatment strategies are incorporating prescription medications in combination with other approaches — such as therapy — otherwise known as Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT). The gold standard in MAT for opioid addiction are drugs like buprenorphine and naltrexone, which drive off cravings without making the consumer high. While such medications have been shown to improve social functioning, lower the risk of infectious-disease transmission from injection drug-use and reduce criminal activity associated with drug addiction, less than half of private-sector treatment programs offer MAT — in part due to an adherence to abstinence-based intervention models among the public and providers, according to a 2014 New England Journal of Medicine article.

For alcoholism, similar medications have emerged, such as disulfiram, which is taken daily and causes nausea and other unpleasant side effects if one ingests even a small amount of alcohol. It’s most effective following detox during the initial days of abstinence, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

SERVICES

Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services

Drug and alcohol withdrawal management, co-occurring mental health and drug addiction in-patient and out-patient treatment, 477-4631

New Horizon Care Centers

Residential and out-patient addiction treatment services and mental health counseling, 838-6092

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Hotline

A confidential and free 24/7 national hotline — in both English and Spanish — for treatment and referral information for people and families facing mental health and substance use disorders, 1-800-662-4357

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Originally from Port Townsend, Washington, Josh Kelety is a staff writer primarily covering Spokane County government, cops, courts, and broader criminal justice issues. Previously, he worked as a reporter with Seattle Weekly. He can be reached at joshk@inlander.com or at 325-0634 ext. 237.