From New York to Spokane, curfews rarely used before this point have been implemented in American cities protesting police brutality in the wake of Floyd’s death when a white officer knelt on the black man’s neck for nearly 9 minutes during an arrest in Minnesota.

While some places like Spokane have made limited use of curfew, with single-night time limits ending at 5 am the morning after being called, others have seen curfews extend for a week, ostensibly making it illegal for many people who aren’t even demonstrating to simply go about their daily lives.

The ACLU has sued L.A. over its current curfew use during protests for effectively eliminating freedom of speech at night, and preventing people who work at night from going about their business. Prosecutors say they won’t pursue fines or charges for those arrested for violating curfew, but while that’s welcome news, it merely adds insult to injury for some who were crammed in buses with their wrists zip-tied for hours, potentially being exposed to coronavirus, the L.A. Times reports.

Implementation of the rarely used public safety tool raises questions of fairness and effectiveness. Little research exists to show whether curfews actually calm situations down or work to clear the area of a demonstration. (If someone is willing to loot or break windows, are they likely to listen to a curfew?) Meanwhile, anecdotal evidence shows that confrontations between protesters and police have escalated in recent weeks once curfews took effect, with police in Minnesota videotaped launching canisters at people who were watching them go by from their own porch.

Historically, the tool has been used with racial bias, aimed at Japanese Americans during World War II, black communities demonstrating during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and enforced largely against Latino and black Americans during the Rodney King riots in the early 1990s.

While police and government officials — who couldn’t remember the last time a curfew was used in Spokane — say a curfew can help them separate peaceful protesters from bad actors, others point out that the very concept of selective enforcement can be harmful in itself. There’s little evidence on how effectively law enforcement can separate criminals from people exercising free speech during a curfew, and by definition, a curfew makes a person out “after hours” a “lawbreaker” subject to arrest and police contact, increasing concerns about biased enforcement.

“The problem with curfew orders is they chill free speech, they open the door to selective enforcement,” says Kendrick Washington, youth policy director for ACLU Washington. “It magnifies the very harms the protesters and the community are demanding be addressed. Here are people protesting the selective enforcement of laws by police and then you issue a curfew that is being enforced against people who are demonstrating against that.”

Spokane’s use of curfew powers last week, and then a request from protest organizers to voluntarily implement a curfew for demonstrations on Sunday, June 7, raised even more questions in the community about how the tool should be used.

WHO SHOULD GO HOME?

As a peaceful march and protest in Spokane on Sunday, May 31, turned into a smaller march through downtown, a few looters breaking into a single store flipped a switch for local law enforcement.

From that point on, police leaders decided that they needed to move quickly to get the crowd out of downtown, even if many people who remained were simply expressing their opinions and not breaking windows, throwing bottles or rocks, or causing any damage, explains Spokane Police Sgt. Terry Preuninger.

He says police at the Spokane County Courthouse had put up with people throwing rocks and other objects at them over the course of hours, which could be considered felony assault.

“To the credit of the people up there, they policed themselves, they without violence got people to stop throwing rocks at police. There were threats and screams, but also some great exchanges; I was impressed with some of the conversations,” Preuninger says. “[But] once that first looting started at the Nike store, with all the other minor assaults, we decided to stop it. It’s no longer a protest: It’s a riot.”

By the time cellphones throughout downtown received a public safety alert to avoid the area due to a “civil disturbance” at 7:53 pm that day, most people there had already seen police using tear gas, flash-bangs, foam and rubber rounds meant to scatter crowds for the better part of an hour.

Still, many remained, trying to continue their protest, kneeling and sitting in the street, holding their hands up, and shouting things like, “Hands up, don’t shoot,” only to see more use of gas, bean bag rounds, and other deterrents.

An hour later, a news release announced Mayor Nadine Woodward was calling for a curfew in the area stretching from Division to Maple and Fifth Avenue to Boone Street, effective immediately through 5 am Monday.

There was no follow up alert to phones, but an announcement on the city’s official Twitter account told everyone to leave immediately, and “In order to disperse people from downtown & give everyone a chance to cool down, Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward enacted a curfew.”

As mayor, Woodward is allowed under Spokane city code to issue a curfew to protect life and property during a civil emergency and natural disasters. That’s what she did May 31, when she and law enforcement leaders decided destructive behavior needed to stop, explains city spokesman Brian Coddington.

“When you started to see a group downtown purely to cause destruction and disturbance, that’s when things escalated,” Coddington says. But on Monday night, June 1, without a large group looting or vandalizing businesses, another curfew was enacted around 8:15 pm. Again, the city said the curfew was due to a large group becoming aggressive toward motorists and others downtown and would last until 5 am the next morning. Spokane Police Department’s Twitter account tweeted, “The reason for the curfew. Agitators have been throwing rocks are [sic] passing cars.”

But multiple members of the media at the park did not see any protesters throwing rocks. Before the curfew, there had been a small fistfight that quickly resolved, and another incident when a man got out of his truck and angrily walked toward protesters while holding a golf club, but the group quickly pushed him back toward his vehicle and he left.

Why not simply arrest the handful of people who’d been fighting? If someone was throwing things at vehicles, why not go speak to them?

“That would be a typical approach, but this isn’t a typical situation,” Coddington says.

Preuninger says that officers monitoring that Monday protest asked for a curfew again to avoid a repeat of the previous night’s events, but that when the crowd controlled itself and kept things peaceful, they allowed the protest to continue for a few hours after curfew. Officers did arrest a man they said they recognized for throwing a Molotov cocktail the day before, and another person who’d gotten into a fight.

“We asked for the curfew, which is a great tool for us because knowing them, we allowed them to exist in that protest. Rarely can you separate the lawful from the unlawful in a protest,” Preuninger says. “Half of them are protesting us, but that’s their right and we’re going to protect that.”

Spokane Police Chief Craig Meidl and the mayor also called for Monday’s curfew after monitoring online threats being made against the protest, Coddington says.

“The goal is to get people out peacefully, without injury and without arrest if possible,” Coddington says. “That’s why the decision was made, based on the totality of what was witnessed, a curfew would be able to accomplish those goals.”

WHEN ORGANIZERS ASK FOR CURFEW

Before another large protest Sunday, June 7, organizers from the Spokane NAACP and Occupy Spokane preemptively asked the city to issue a curfew at 8 pm that night, saying officially that they wanted protesters to respect the time frame of 2 pm to 7 pm for action, and voluntarily leave by 8 pm.

Social media channels quickly lit up with people questioning why organizers would ask for a curfew, which can result in arrests, when everyone had agreed last week that those breaking into and vandalizing businesses were not part of the protest for police reform.

“We landed there not only because of what happened at the first protest, but also the level of intelligence that kept coming through about agitators, instigators, outside influencers, and white nationalists,” says Kurtis Robinson, Spokane NAACP president. “For people to have a problem with that being called for, it’s like, ‘Did you see what happened last time?’”

Part of the problem, Robinson says, is that people weren’t made aware of the expectation last time. This time, organizers wanted to set the tone early, not blindside people, and let them know they supported a powerful protest for serious action.

“We can’t do what happened last time, and we can’t do what’s happening all across the rest of the United States, including Washington state. Let’s be better than that, and call for the things we need to call for,” Robinson says. “We’re talking about the ability to have our voices heard, and heard loudly, for as long as we needed, and I think that got accomplished.”

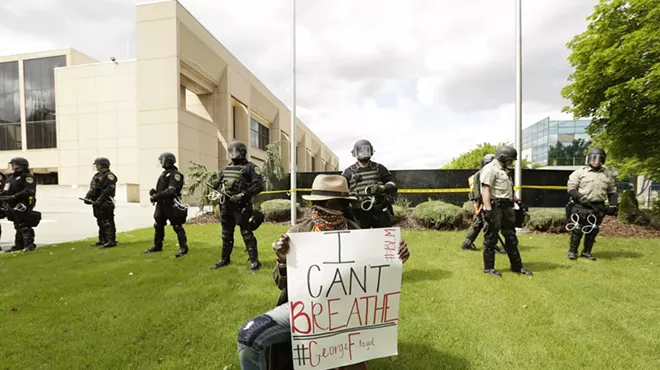

Still, a group of a few hundred continued marching downtown past the suggested curfew, which was never made official by the city. But a patrol of bicycle officers mostly stayed back from the group, and even when the march went to the courthouse, which was heavily guarded by police from multiple agencies in riot gear, things remained peaceful.

WHO’S DANGEROUS, WHO ISN’T

But what about when a curfew or order to disperse seems unfair? Why were some people who showed up on May 31 open carrying their rifles allowed to remain downtown for a time after dispersal orders, while others kneeling in the street were met with tear gas?

Whether people think Spokane’s curfew was applied fairly or not, Preuninger says the curfew was actually one of the only reasons officers were allowed to eventually ask people who showed up armed to leave.

“If there wasn’t a curfew, they would’ve been able to come and walk around town because carrying the way they were was not a violation of the law,” says Preuninger, who responded with other officers in riot gear.

But many others were met with tear gas and “less lethal” rounds when they refused to leave.

Preuninger emphasizes that, “For the record, we don’t have any rubber bullets.” The department does, however, use foam and sponge rounds meant to mimic the strength of a baton strike, he says. They also have rounds that contain 42 rubber balls that are meant to be shot at the ground to scatter.

“Make no mistake about it though. This stuff would never be used on a lawful protest,” Preuninger says. “You have to remember the moment we give those dispersal orders and people are throwing rocks at police, that’s not a peaceful protest. It’s a crime to stay.”

Preuninger says he knows that the majority of people are not criminals, and his officers do want to support First Amendment rights, but if those around you are throwing things, even if you don’t see it, officers feel they have to act.

“If you’re getting gassed, you’re a rioter,” Preuninger says. “You may not be in the act of rioting, but once those dispersal orders are being given, it’s unlawful for you to be there.”

But what are the legal scenarios for officers to use those types of dispersal weapons, asks Washington, the lawyer with ACLU’s Seattle-based office. When you have protesters on their knees in an intersection saying “Hands up, don’t shoot,” like they were in Spokane, and you fire tear gas, that is not the purpose of those weapons, Washington says.

“I get the cops are tired, I get they had something, maybe a bottle, thrown at them earlier in the day,” he says. “But when you’re using the lethal or less-lethal force you’re supposed to be reacting to what’s happening in front of you, not what happened earlier in the day.”

By nature, Washington says, most protests intersect with the law, as people rush into the streets, blocking traffic for a march, or as they protest a curfew itself.

“A protest in and of itself is always in conflict with some set of laws. The government decides which sections they’re willing to suspend or not enforce,” Washington says. “Curfews are meant to maintain order. These are being issued to control a certain segment of the population. They want to help the police get off the street, they want a break, but that’s not the authority on which the right to issue a curfew rests.”

Protesters may be able to argue that curfews are overbroad, he says, applying to a whole city, for example, when protests are focused in one neighborhood, or being used to control protests where safety concerns aren’t clear.

“I’m sorry the police are tired. I’m sorry they want to go home, but black people are tired, too. We’re tired of blacks being killed. We’re tired of being told we’re a threat. We’re tired of people fearing us simply because our skin is dripped in black,” Washington says. “For all the weariness of the police, it’s not a fraction of the weariness the black population is feeling. They need to sit tight and sit in their discomfort.”