This Saturday will be the longest night of the year. The sun will set at 4:01 pm and stay down for over 15 hours.

In these days leading up to the winter solstice, communities around the country hold memorial services for people without homes who died this year. Cold nights are particularly dangerous for people living on the streets, as deep stretches of bitter darkness increase the risk of frostbite and hypothermia.

This morning, CHAS Health hosted a memorial at its Denny Murphy clinic on Second Avenue in Spokane to commemorate 200 homeless people — and most likely more who haven't been identified — who died in our area in 2024.

A couple hundred people gathered in the parking lot, about the same number as those memorialized. The attendees were CHAS healthcare workers, including members of the Street Medicine and Homeless Outreach teams, plus people without homes, housed community members, and local elected officials.

Most people there were bundled in scarves and gloves, and many attached small purple memorial ribbons with tiny bells to their puffy coats. There were tables lined with warm carb-rich foods, hot coffee and tea, and free doses of naloxone, a medicine that rapidly reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.

Shelby Lambdin, health equity director for CHAS, started the ceremony.

"For many, nights seem too long," she said, but for the more than 2,000 homeless people in Spokane County and the 650,000 nationwide, cold nights can be especially unbearable.

Lambdin said that CHAS served over 29,500 unique patients experiencing various levels of housing instability this year, whether that meant they were sleeping in shelters, on couches, or in cars. That's 5% more patients than 2023.

"No one person has a definitive solution to homelessness," Lambdin said, but she encouraged listeners that "collective compassion" can ease the burden on individuals and society.

After her speech, the crowd shifted its attention to a video introduced by leaders of the Street Medicine team, who said that every person who dies without a home has a story that deserves to be remembered.

The video opened with people living on the streets talking about their friends who died this year.

One woman remembered a woman she considered her "street mom," who was a "mother hen" to lots of younger people on the street until she died of liver failure, noting, "Downtown is not the same without her."

One man shared a relatable regret: "I wish I was a closer friend with him, but we both liked the same girl."

Another woman was grieving the deaths of 24 friends in one year.

Then, CHAS employees read 200 first names and last initials, giving a moment of silence between each person lost. The audience was still, with mostly set chins, though a few tears slipped through.

"The longer you do this job, the closer you get to people, the more people you know," says Emily Fejeran, a registered nurse on the Street Medicine team.

It's her third year doing this kind of work — salving wounds, injecting long-acting psychiatric medicine, driving around for hours to find a patient who's due for another dose.

"This year, personally, I know more names than I did the last two years."

Relationship is at the heart of her work, Fejeran says. It's a misconception that street teams deal only with drug addiction or mental health issues. People without a home get the same illnesses as people with a home, but they face more barriers to getting basic treatment.

Something that could have been treated with antibiotics or a basic procedure turns into a chronic issue, she says. The street medicine team has been providing care to the same 25 patients every month all year. It's completely different than her previous hospital job.

"Your patients are so grateful," she says. "They're so respectful. They're just so happy to receive care. It's just such a different area. I've never felt this way working in health care before. I think in the hospital, you're kind of forcing treatment on people. A lot of the time out here, they're seeking treatment. They want treatment. They enjoy talking to you. They just like saying hi. You're able to give them outreach supplies and form a relationship. So it's people that you get to see over and over again."

Most of the ceremony was spent grieving friends and patients that those gathered knew. But there was also a moment of silence to remember those whose names weren't recorded, who died "unidentified or in loneliness," as one speaker said.

The silence was broken by a soft tinkle of bells, when those wearing the purple ribbons fluttered their collars.

The crowd was then released to decompress with hugs and hot macaroni and cheese.

This year's memorial video will be available online throughout 2025, as providers continue to "work for a world where no life is lost to homelessness," as one Street Medicine team member put it.

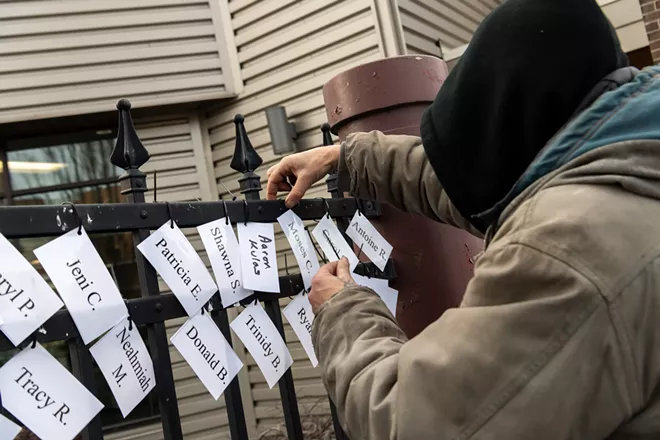

But each name is also written on a white index card currently hanging on the fence in front of the Denny Murphy clinic. They will flutter there until the end of the year, unless violent winter weather rips them down.

Anyone who stops to read a card will be honorarily included in Lambdin's closing remark: "It is because of your attendance today that these people will not be forgotten." ♦