Standing at a podium outside a homeless shelter in the midday heat on June 3, Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward celebrated the city's new approach that, she said, increasingly emphasized getting people out of homelessness, and not just off the street.

"I'm the only one representing the city for this announcement," Woodward said when asked why City Council members hadn't been invited to the press conference. "These are operational things. These are things that I'm in charge of doing."

Yet, as Woodward touted the city's partnerships with Spokane County and local nonprofits, internally the city's division in charge of addressing homelessness was about to be hit with another blow.

On June 14, Cupid Alexander, the city's director of neighborhoods, housing and human services division, abruptly announced his resignation, effective July 30. And on Wednesday, after being told he'd have to use his time off instead of continuing to serve through July, Alexander sent out a fiery email.

Arguing that other city employees hadn't been treated this way, he accused City Administrator Johnnie Perkins, who had been in that job barely two months, of racial discrimination.

"I can say without a shadow of a doubt that this has been intentionally unethical, unequitable, worst-practices and a direct mistreatment that I can attribute from YOUR treatment of me, Johnnie, to my race," he wrote to Perkins. "As the lone black employee I'm tired of this treatment."

"The allegations Mr. Alexander made in the email are very serious," a statement from the city of Spokane reads. "Racism has no place in the organization, community or country."

A day later, Woodward announced a third-party investigation into Perkins. The city cited that investigation as a reason not to answer any additional questions about any of the issues Alexander raised in his emails.

"We need to respect the investigation process and give it space to play out," city spokesman Brian Coddington wrote, turning down Inlander requests to speak with several different officials.

Yet as Alexander left, he forwarded a slew of emails to City Council members that not only outlined his concerns about racial bias, but detailed dysfunction at City Hall and suggested that Woodward's administration had been intentionally withholding information from the council.

It's exactly the kind of public reckoning that Alexander accused Perkins of trying to avoid.

"You came to my office and tried to intimidate me into NOT sending you emails because they are 'public record' and to just 'talk' to you," Alexander writes in one email. "You were worried [about] the public information. Leadership requires accountability. I have been accountable for EVERY thing I've done here."

When Woodward stepped into City Hall in January 2020, she found a lot of empty desks. Former Mayor David Condon had left a slew of vacancies, arguing that his successor deserved a chance to build out her own team.

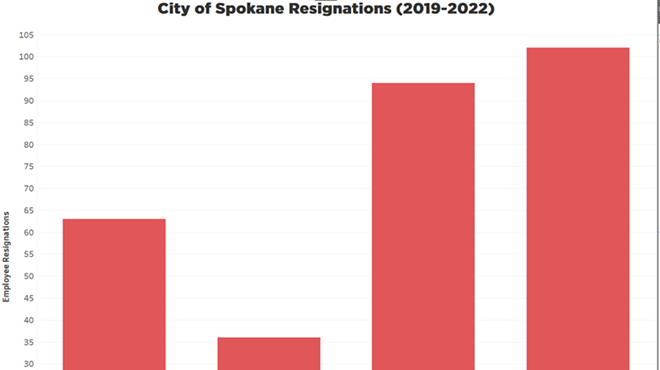

Yet Woodward's picks have been rife with turnover. Her first pick to lead the human resources department left within a few months. Her first city administrator pick, Wes Crago, resigned with little explanation in September.

"We will get through this," Woodward wrote at the time in an email she sent to herself to print out, "we will not lose ground but we will have better direction in [carrying] out my initiatives."

Two months later, in November, Woodward hired Alexander to run the neighborhood services division, calling him "someone our community partners will find engaging and collaborative."

In one sense, it was a surprising choice: Woodward had campaigned for mayor on a conservative platform that savaged the city's homeless shelter approach as "enabling" addiction and encouraging more homeless people to move here. Alexander, meanwhile, was a mayoral adviser in left-wing Portland.

Part of Alexander's job was to oversee the Community, Housing and Human Services Department, the frequently troubled department in charge of the city's shelters and homelessness.

For years, as an understaffed and overworked CHHS repeatedly struggled to find enough warming centers and shelter space, the department was hammered by the administration, the City Council and the public. When Alexander took the helm, in the middle of the pandemic, the department was already plagued by turnover. And the turnover only got worse after he took over.

The Community, Housing and Human Services department's senior manager, Tija Danzig, left in March. The department's director, Tim Sigler, who had already been on leave for months, resigned shortly after.

City Councilwoman Lori Kinnear doesn't believe that Alexander's leadership style was to blame. It was the unreasonable workload they faced.

"[Danzig] was working in excess of 80 hours a week," Kinnear says. "Because we were understaffed, she was being asked to do things at a pace that was not really humanly possible or sustainable."

Today, there are seven vacancies within the CHHS department. With each employee who left, more and more work was heaped on the remaining staffers, including Alexander.

"They took MONTHS of leave off with zero notice, leaving me and others to scrape together the work — even as I was a new employee who received ZERO onboarding," Alexander wrote in his email to Perkins last week.

Sigler "has been gone a majority of the six months I've been here," Alexander wrote in one exasperated email in May. "I have no deputy. I have no appointed individual. I am taking on the CHHS director role."

He recounts taking medical time off because he'd been focusing so many months trying to "right the ship" at City Hall. But when a new city administrator finally arrived in April, it didn't make Alexander's job any easier.

As Perkins started to try to get up to speed, he'd send Alexander lists of questions and assignments. But Alexander appeared to grow increasingly irritated with what he saw as Perkins' lack of responsiveness or clarity. He'd been "iced out" from crucial information and major meetings, he wrote, and sent on "fools errands" to complete busy work that the administration didn't bother to use.

On May 20, a lengthy email from Alexander to Perkins brimmed with animosity, detailed weeks of grievances and listed 13 different email messages he'd sent to Perkins that the city administrator hadn't responded to.

In the email, which Alexander shared with the City Council, he wrote that he felt "personally targeted."

Spokane's City Council members across the ideological spectrum have showered Alexander with praise for his housing expertise and his willingness to share what he saw as the unvarnished truth.

"He's very pointed about what he says: 'Here are the facts,'" Kinnear says. "Boom, boom, boom."

Yet in both Portland and Spokane, there are people who tell the Inlander that Alexander's intensity and confidence could sometimes come across as blunt or dismissive.

In his email to Perkins, Alexander accused the city administrator of attacking him with vague intimations that Perkins had been "'hearing' things" about him. Alexander was more direct in his response.

"I have emails from colleagues indicating ... that our meetings with YOU are the worst they've been in," Alexander writes to Perkins, saying he could prove it. "You can deep dive my emails."

Much of the investigation into Alexander's allegations will focus on the concerns he raised about discrimination.

"You said your 'son' said I looked athletic and asked if I played sports," Alexander wrote to Perkins. "Stereotyping me in every possible way imaginable."

Alexander has raised these kinds of concerns before. Several in Portland cited instances when Alexander would call out what he saw as racially loaded rhetoric, sometimes in response to criticism he'd received, and sometimes more generally.

Betsy Wilkerson, the sole Black woman on the City Council, stresses that such concerns should be taken seriously.

"The question folks of color have asked is, 'Don't you believe me?'" Wilkerson says. "Most people don't go around making up and playing the race card any chance they get."

The issues Alexander raised go far beyond how the administration treated him.

Woodward's June 3 press conference celebrated the department's decision to extend a contract with the Guardians Foundation to run the Cannon Street shelter. But in a May 20 email to Perkins, Alexander wrote that he "kept staff from pretty much walking off the job because they disagreed" with the administration extending the Guardians' contract.

In April, a state audit concluded that the CHHS department previously had been pressured to circumvent policies and procedures. Yet Alexander's emails suggest Woodward's administration was pressuring the CHHS department to extend the Guardians Foundation's contract by 90 days without following a formal request-for-proposal process — exactly the sort of issue the audit had flagged.

While Perkins argued that the city attorney said there was no legal issue, Alexander countered that "legality isn't the issue — process and precedence is."

And while Woodward has highlighted regional collaboration around homelessness, Alexander's emails raised concerns that the informal regional group discussing homelessness had created yet another messy layer of bureaucracy.

"The regional leadership table is further confusing as it holds no charter, therefore any decisions would be an obstruction of [public] meeting laws," Alexander wrote to Perkins in a May 5 email.

Woodward had also told reporters at the June press conference that the recent "point-in-time count" of Spokane's homeless population concluded that — despite homelessness increasing in recent years — the city needed to do a better job of using existing shelters to move people out of homelessness, instead of adding more shelter spaces.

When reporters expressed skepticism of the premise, Woodward doubled down.

"That's what they came up with," Woodward says. "That's the recommendation of the CHHS staff."

But it wasn't.

When the actual report about the homeless count was finally released, it clearly recommended considering both adding more shelter spaces and reworking the existing ones.

In his emails, Alexander suggests that the administration had intentionally withheld the point-in-time count report from the City Council for at least a month. He wrote that the administration was trying to make sure the point-in-time count didn't "disrupt" the mayor's housing and homelessness plans, "as other entities were prepping to attack" it.

Considering the apparent lack of transparency, Wilkerson wonders if the trust between the City Council and the Woodward administration might be damaged.

"The honeymoon might be over," Wilkerson says. ♦