On a large overhead screen, red dots pepper a map of Spokane. Each dot marks a specific crime committed within the past week. Ryan Shaw, senior crime analyst for the Spokane Police Department, points out the different criminal “hotspots” across one troubled neighborhood.

“We’ve noticed several,” Shaw says.

The analyst brings up a new screen pinpointing recent vehicle prowl locations. Another screen lists times and places for commercial burglaries. He then pulls up mugshots of repeat offenders in the area, reading off their addresses, criminal histories and known associates.

Spokane Police commanders and more than a dozen other regional law enforcement officials gather for a newly organized “CompStat” strategy meeting. Coffee cups and data reports litter the conference table as they listen to Shaw’s briefing. They exchange arrest figures, crime trends and community complaints.

With the start of the new year, Police Chief Frank Straub has ordered a department-wide reorganization around a new CompStat policing model. The popular, but somewhat controversial, management model hinges on complex crime analysis, using statistics to deploy officers to problem “hotspots.”

To make the transition to CompStat, Straub has restructured divisions and replaced his executive staff. He has given new authority to field commanders and expanded community outreach. He has also rallied his officers around the numbers.

“Our strategies and tactics will be guided by data, information, intelligence, and evidence-based practices,” Straub wrote in his 2013 Strategic Plan. “We will, over the next five years, develop and utilize predictive analysis to anticipate criminal activity and introduce strategies that ‘head crime off at the pass.’”

Despite recent increases in Spokane crime rates, the chief hopes hard numbers could become the department’s greatest new weapon.

CompStat, short for Comparative Statistics, is a management system for tracking crime rates and holding local commanders responsible for their results. The New York City Police Department first introduced the model in 1994 to map crime in the subway system. Dozens of other medium- and large-sized cities have since adopted enforcement models similar to CompStat.

The approach revolves around weekly strategy meetings. In those meetings, crime analysts provide information on emerging patterns and possible criminal connections. Law enforcement officials share information, review recent crime statistics and discuss enforcement efforts for the next week. Local supervisors must also answer for crime numbers in their sections and present strategies for preventing future issues.

Straub, a former assistant commissioner with the NYPD, championed CompStat during his time with the Indianapolis Metro Police Department. His new strategy for the Spokane Police Department echoes the central elements of CompStat, giving field commanders flexibility to manage their own people, but also closely monitoring their impact on crime rates.

Critics of CompStat argue the model promotes a number-obsessed police culture that creates ever-increasing pressure to drive down crime rates. Professor Eli Silverman, a national authority on CompStat at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, says the model has several pros and cons.

“CompStat is a great management tool for holding local commanders accountable,” he says.

But when pressure increases to keep crime rates down, CompStat can also lead to micromanaging, Silverman says. Stressed supervisors may push heavy-handed policies or quotas for better results.

A few departments have also struggled with reports of local officers changing the classifications of certain crimes to make their statistics look better, he says. A robbery can be changed to a theft or an aggravated assault is listed as a simple assault to improve the appearance of the numbers.

“The whole system is then distorted,” Silverman says. “If the police department is the only agency to report on the legitimacy of its own numbers, then that’s a fox in the chicken coop.”

The problem was fictionalized in HBO’s The Wire when police officers were caught “juking the stats” to make their local crime rates look better. Silverman, who recently wrote a book on the issue called The Crime Numbers Game, says departments can prevent distortions by having an independent agency review their numbers.

Experts say the CompStat model works best when combined with community partnerships to address nuisance problems like graffiti and abandoned cars.

The Crime Analysis Unit, once an isolated program, now sits centrally in the Field Operations Division alongside patrol detachments and the Major Crimes Unit. Maps and mugshots cover the walls as a team of analysts run the latest numbers. This week they have also started a 40-hour training course on new crime tracking software to improve CompStat reporting.

Cmdr. Brad Arleth, who oversees Field Operations, says he has worked to incorporate the new data into investigations, deploying patrol officers and making arrests based on incoming intelligence from Crime Analysis. Detectives in Major Crimes can also tap into the new information for their cases.

“We’re much more nimble and much more able to react and respond to crime trends, patterns and issues,” Arleth says, adding, “Really what we’re striving for is to try to get ahead of the curve on some of those things.”

While Arleth leads patrol and investigation, Cmdr. Joe Walker runs the other side of the department, the Tactical and Strategic Operations Division. Walker says his division works to get out in front of crime at the street level, incorporating Neighborhood Conditions Officers, property crimes, fraud and tactical operations.

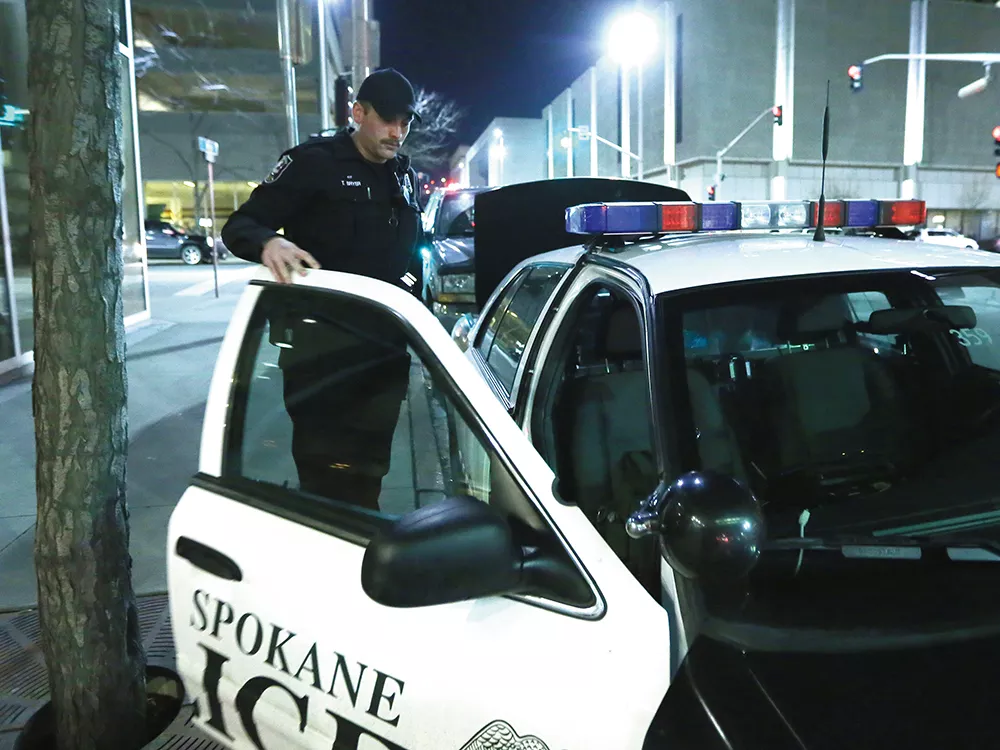

A key piece of the restructuring involves assigning seven new officers to the downtown area as Neighborhood Conditions Officers. Those officers, pulled in from other units, will work toward addressing the community nuisance and abatement issues. They can visit downtown businesses, conduct foot patrols and respond to local complaints.

“Look at this and think of proactive [policing],” Walker says. “They’re actively looking for … neighborhood problems and concerns, drug dealing, gangs.”

In the weekly CompStat meeting, Arleth and Walker must go over their crime numbers and explain their results. Then Straub, analysts and other officials can ask questions or make suggestions for the upcoming week.

Both commanders say the new structure has broken down communication bottlenecks and improved staffing flexibility. The more horizontal organization can shift resources to problem areas and collaborate more easily across units.

“Things were a lot more siloed [before],” Arleth says. “They took a lot more of a bureaucratic process under our previous administrations. … We had a less defined objective and set of priorities. Now there’s no question.”

While moving to CompStat has been a significant transition, department officials expect more change in the coming months. Officers will undergo new crisis and outreach training. Administrative duties, once scattered across divisions, will now go through a central Business Services Bureau. A public relations manager has joined the team.

The department has also welcomed a new assistant chief with Straub recently naming Major Craig Meidl to the position. Former Assistant Chief Scott Stephens remains on administrative leave for unspecified reasons.

Meanwhile, city officials have started campaigning for new funding to hire additional officers and purchase body cameras. Voters will soon decide whether the Police Ombudsman should have independent oversight authority. The city’s Use of Force Commission also recently released 26 recommendations on reforming the department’s culture and operations.

So it’s a busy time for the Spokane Police. Department officials say they have worked long hours in recent weeks of transition, but they remain excited about the future.

Straub, and the rest of Spokane, will be watching the numbers.