Like state governments across the country, IDAHO was anticipating that COVID would blow a bazooka-sized hole through their state budget.

When the pandemic hit, Alex Adams, Gov. Brad Little's budget director, says they thought the state would take in $700 million less in tax revenue than they'd projected before the pandemic — $300 million less if they were lucky.

Instead, the exact opposite happened. Idaho began to take in a lot more tax revenue than they thought they thought before the pandemic.

As of December, their unemployment rate was at a 3.8 percent, even better than Washington state's unemployment rate before the pandemic.

In part, Adams credits the governor's "quick and surgical actions to prepare for the worst." While Idaho did mandate that some businesses shut down, the lockdowns were a lot shorter and a lot less strict than states like Washington. For example, they didn't shut down home construction at all.

While other states saw their tourism industry flounder, Adams says Idaho's tourism, heavily reliant on the sort of outdoor recreation where social distancing is possible, dodged the impact.

And not just parks.

But Idaho's booming economy may have been bought for a steep price: More than 172,000 Idahoans have been infected with COVID. More than one out of every 1,000 Idahoans — 1,879 people — have died from the virus. Adjusted for their populations, Idaho has suffered over twice as many COVID infections as Washington state and 57 percent more deaths.

If Idaho had been as successful as Washington at fighting COVID, the state would have 680 fewer COVID deaths.

"We took the forecast way down, by $9 billion over three years. We did a hiring freeze; we asked agencies for cut drills," he says. "It was kind of a 'Uh oh. If this really happens, we're in trouble.'"

"All of a sudden what we realized is the economy it has slowed down some, but not drastically," Schumacher says. "People are still spending their money."

"In terms of our budget situation, revenue losses is not what we're experiencing," McMullen says.

First, he says the state isn't taking advantage of Oregon's corporate activity tax. But maybe more importantly, there's a quirk in Oregon law called a "kicker" credit. Whenever Oregon income tax revenue comes in significantly higher than projections, instead of the gains being funneled into the general budget, they're set aside and eventually sent back to the taxpayers.

"When the pandemic hit, we blew a $2 billion hole in the budget, assuming that all of those job losses were going to turn into revenue losses," McMullen says. That didn't occur."

So while the state actually took in a lot more revenue than it expected, because of the kicker rule, it doesn't actually get to use a lot of that revenue.

Sometimes, that kicker can set the state up for a budget nightmare: Right before the Great Recession hit in 2008, he says, the state gave out a massive kicker, leaving state coffers depleted heading into economic collapse. McMullen says that's not happening here.

SPECIAL K

As with most things these days, the state revenue data has become a partisan inkblot test.

In Idaho, Republican politicians like Gov. Brad Little and U.S. Sen. Mike Crapo have used Idaho's success as a cudgel against the Democrats' $1.9 trillion stimulus proposal, arguing that the $350 million targeted at state budgets will end up rewarding "irresponsible" states that put into place more stringent lockdowns at the expense of their economies.

.@GovernorLittle is right. Idaho shouldn’t have to subsidize irresponsible states experiencing increased unemployment while continuing to keep businesses, school and churches shut down. https://t.co/Dc8mOdM34i

— Senator Mike Crapo (@MikeCrapo) March 5, 2021

"One of the lessons of the last recession is the deep cuts prolong the recession," Washington state Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig says. "One of the reasons that Washington has done better is we have not had a knee-jerk reaction to cut services at the time when people need help."

Yet, as both Republicans and Democrats will tell you, there's a dark story hidden among the positive state revenue news.

If you average the two lines, like with state revenue, you'll miss the real trend: The economic tide has lifted some boats and capsized others.

"I'm standing outside right now in my front yard," says Schumacher, the Washington state Office of Financial Management director. "I would bet you money that an Amazon truck goes by while we're talking."

Whether you buy a book from Auntie's Bookstore or Amazon, Washington state collects the same amount of sales tax from your purchase. So the state makes out just fine.

But smaller businesses have been hurting, says Volz, the Republican legislator from Spokane.

(In Idaho, which relies on both income taxes and sales taxes, income tax collections rose much faster than sales tax collections.)

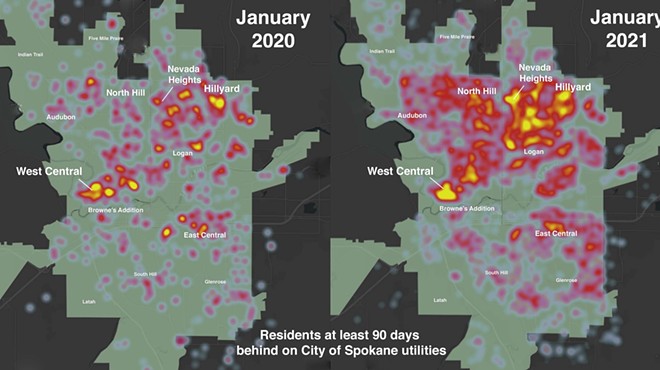

That's great if you're a Realtor. But the high demand has made an already existing housing crisis in the Pacific Northwest worse. Vacancies are at record lows in Spokane. Rents keep climbing. The number of people who can't pay their rent or their utility bills keep increasing.