Have you ever wondered what a cloudy day sounds like? Or possibly what tune your heart beats to? Maybe you're curious about trees falling in the woods when you aren't there to hear them?

Well, thanks to research spearheaded by Jonathan Middleton, that may soon be possible.

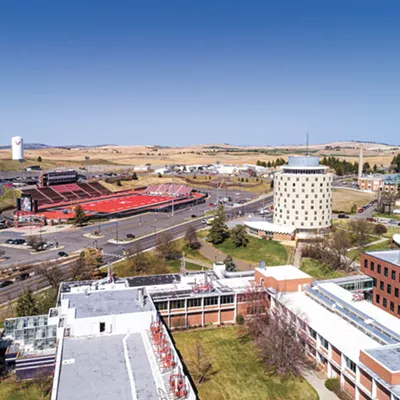

Middleton, a professor of theory and composition in Eastern Washington University's music education program, recently published a research paper in Frontiers in Big Data — "Data-to-music sonification and user engagement" — which looks to reveal how musical characteristics can have analytical purposes. He worked with 10 other researchers hailing from Finland's Tampere University, EWU's school of business and Bentley University in Massachusetts.

Essentially, he's turning data into music.

"We live with sounds all the time," he says. "It's only a matter of time before phones can play a musical riff that tells you the weather for today."

By programming a data-to-music mapping software over three years, Middleton and his research team were able to create an algorithm that outputs different music depending on the data input. Different datasets can be assigned specific musical attributes, such as pitch, rhythm, duration and scale.

Take the weather, for example, one musical stream may represent the cloud cover for the day while another might represent the wind speed, according to Middleton's paper. The two streams can then be played together to make a more complete and complex string of music.

As you can imagine, Middleton had to get creative with how he directed the program to convert data points into musical notes in order to produce something that both sounds pleasant and makes logical sense.

For instance, meteorologists assess cloud cover at their weather station in "oktas" — a unit of measurement that splits the sky into eight sections of a circle to estimate how much is covered by clouds. Zero oktas means it's a completely clear day, while eight means it's completely overcast.

At first, Middleton's algorithm played a higher pitch for the higher-okta cloudier days, and a lower pitch for sunnier days, so he flipped the pitch scale. Now, when a day is bright and sunny, his algorithm produces a higher pitch and a lower sound for cloudy days.

"It's only a matter of time before phones can play a musical riff that tells you the weather for today."

This isn't a new discovery for Middleton, who's been thinking about algorithms that can take a source of data and translate it into musical sounds for nearly two decades now. In 2004, he and a team of EWU computer science students created a tool — musicalgorithms.org — that allows folks to create musical representations of the data they want to input.

"We feel like we can graph anything, but that usually comes as a visual display," he says. "I think adding an auditory display may help some data scientists better understand their research."

He believes that this work offers a symbolic fourth dimension to the way people understand their datasets. Unfortunately, his most recent research doesn't dig deep enough for Middleton's curiosity.

"The paper I wrote isn't the paper I wanted to write," he explains. "It was the paper I had to write because there wasn't any paper like it yet that took the leap of faith that you can mix musical ideas as a representation of data.

"A lot of researchers in the community are very hesitant to cross the line into making musical sounds out of the data, so I had to write something that would cross that line," he continues.

Middleton says that his recent research essentially created the field that he wants to play on. Moving forward, he wants to examine how musical datasets can be put to use in practical applications.

If all goes well, he hopes that this data-to-music research could be used in the medical field.

"If I could help doctors diagnose diseases, that would be truly amazing," he says.

But even then, he doesn't think this type of work will make its way into the mainstream for a while.

"We'll need like 10 of these types of studies to firm up the research," Middleton says. "It might take awhile, but I think this will help researchers understand and engage with their data in new, accessible ways. "

If all goes well for Middleton, he hopes to have his next research paper published by June 2025. ♦