Spokane owes its existence to bridges.

A roaring river cuts the city in half, and since the earliest days of white settlement, planners and politicians have looked to bridges to unite the city's economy and society.

The first were rickety, wooden footpaths that were frequently swept away by floodwaters. Many were replaced with steel structures that were able to accommodate horse-drawn carriages and electric trolleys.

The steel structures still presented problems. Multiple tragedies — including the collapse of the Division Street Bridge in 1915, which sent a streetcar into the river and killed five people — prompted demands for a more stable solution to Spokane's bridge problem.

The solution: concrete.

In his 2013 book Bridges of Spokane, Jeff Creighton, a former assistant archivist for the Washington State Archives, describes a "bridge frenzy" in Spokane between 1907 and 1917 that saw construction of many of the iconic bridges that define the city to this day. Many of the rickety steel-beam bridges were replaced with reinforced concrete arch structures — an innovation at the time that wasn't without risk.

Spokane was "somewhat leading edge" when it came to construction of concrete bridges, says Kyle James Jarvis, a local infrastructure history enthusiast. Some of Spokane's concrete arch bridges were lauded throughout the state as feats of engineering.

Today, the city's bridge division inspects and maintains 66 bridges — 43 vehicular and 23 pedestrian. Doing repair and inspection work in a city with so many 100-year-old bridges can present unique challenges. A "symphony of things" needs to happen to coordinate schedules and try to prevent multiple bridges from being closed for maintenance at the same time, says Kirstin Davis, a spokesperson for the city's public works department.

Bridges unite Spokane, but they also divide it. Incredibly expensive to build and maintain, they've long been a source of political and financial headaches. In his book, Creighton describes how the era of frenzied bridge building prompted scandals and allegations of corruption that doomed political careers and sparked numerous controversies at City Hall. There was also tragedy. A number of workers died while building the concrete behemoths.

Construction methods have grown safer and more efficient in recent years, but the costs are still astronomical and often exceed what the city can handle on its own. When bridges close for maintenance, it can snarl traffic and frustrate commuters for months.

And in recent years, bridges have also come to represent many of the city's greatest social problems. As Spokane's homelessness crisis worsens, city leaders have struggled to respond as more and more people use bridges not as a means of transit, but as shelter.

Spokane is a city defined by bridges. Despite ongoing challenges, they stand today as feats of engineering — landmarks to the city's complicated past, present and future.

— NATE SANFORD

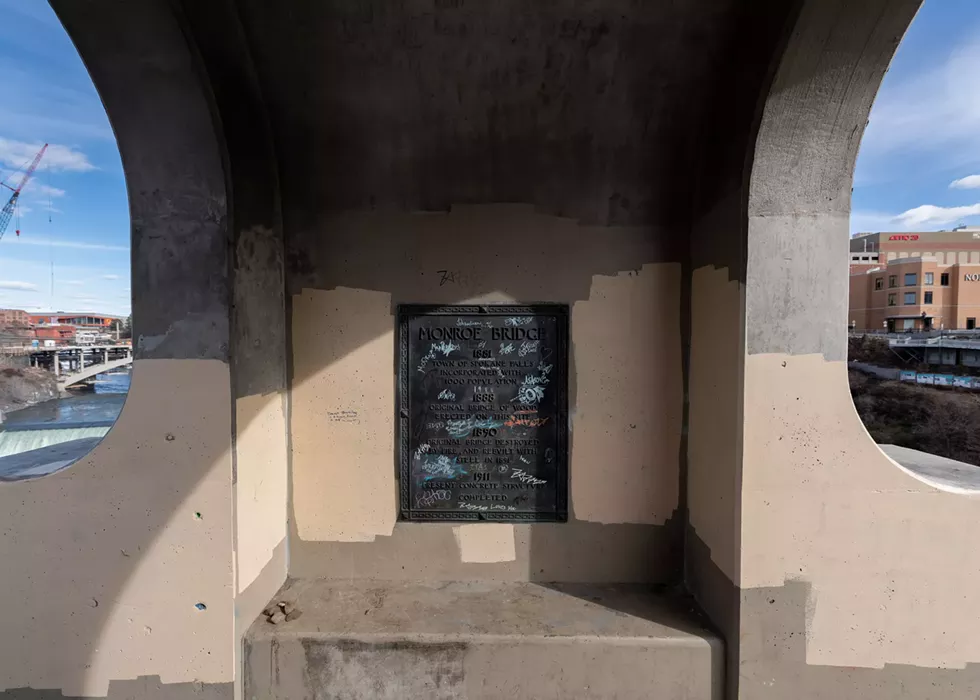

MONROE STREET BRIDGE

YEAR BUILT: 1911HEIGHT: 136 feet

LENGTH: 896 feet

ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION COST: $500,000 ($15.7 million in today's dollars)

The Monroe Street Bridge is perhaps the most iconic bridge in Spokane — a massive feat of concrete engineering that towers over Spokane Falls and the river gorge and runs straight through the heart of the city.

The bridge connects City Hall and the downtown businesses with Kendall Yards and the county government offices on the north side of the river. The views are majestic. During the river's peak springtime flow, the roar of the rushing water 136 feet below the bridge is almost enough to drown out the cars rushing past you on the bridge.

The first iteration of the Monroe Street Bridge was built in 1889. It was made of wood and, predictably, burned down in 1890. It was replaced by a steel bridge that opened a few years later, this time with double-track lines for electric streetcars, which shared the bridge with horse-drawn buggies and wagons.

But the new steel bridge was still flimsy. In 1907, a pair of circus elephants reportedly refused to cross the rickety structure. In 1910, the bridge partially collapsed.

Construction on the new bridge began soon after. Instead of contracting the work out, the bridge was designed and built in-house by the city.

City Engineer John Chester Ralston designed the bridge, copying the design of Rocky River Bridge in Cleveland, Ohio. Construction was difficult and resulted in the deaths of at least two workers.

The bridge was finished in 1911 and opened with a grand ceremony. At 136 feet tall and 896 feet long, the bridge was the longest reinforced concrete arch in the U.S., and the third longest in the world.

Mayor W.J. Hindley gave a dramatic speech where he made pointed comments about the lack of organized labor representation at the opening day's festivities, and declared that the Monroe Street Bridge would "be here for a thousand years to mark the spirit of progress prevalent in the Inland Empire."

The bridge has a concrete arch design that would come to dominate Spokane's bridge-building landscape. According to Bridges of Spokane, designers originally planned to ornament each alcove with "cast-concrete profiles of American Indians," but the plan was later scrapped in favor of the bison skulls designed by Spokane architects Kirtland Cutter and Karl Malmgren that guard the bridge today.

The Monroe bridge was closed between 2003 and 2005 for an $18 million restoration project that replaced cracked columns and arches with new concrete that should last at least 75 years.

The bridge has four small alcoves with benches inside. The alcoves — also known as porticos — were almost removed from the design. The Spokane Daily Chronicle reported in 1911 that city leaders worried they would become a haven for "hold-ups and spooning couples." The city went ahead with the project anyway, hoping bright lights would dissuade people.

"Spooners must sit in glare of lights," the headline read.

More than a hundred years later, city leaders are once again fretting about how people use the alcoves. But spooning couples are the least of their concerns. As Spokane's fentanyl crisis grows, it's become common for at least one of the alcoves to be occupied by a group of people smoking the drug. It's a part of the urban landscape familiar to anyone who travels the city on foot: a flash of tinfoil and a sickly sweet acidic smell.

Last summer, Spokane City Council member Michael Cathcart and his wife were walking across the bridge with their young son in a stroller. When they passed through an alcove, Cathcart says a man sitting on one of the benches blew fentanyl smoke in their faces.

"There was nothing I could do," Cathcart says. "Once you're in the alcove or close to it, you have no options, you're literally stuck."

The incident prompted Cathcart to introduce a resolution last fall asking city officials to look into design changes to discourage criminal activity. The resolution asked that officials balance the competing goals of safety and historic preservation. Removing the alcoves altogether might be the most effective solution, Cathcart says, "but I don't have any interest in destroying our heritage and our history."

"I don't have any interest in destroying our heritage and our history."

Last week, the city's police and public works departments came back to the City Council with a set of recommended solutions. One of the biggest proposed changes is to install steel plating over the benches at a 45-degree angle to prevent people from sitting or lying down.

Patrick Striker, the director of the city's Office of Neighborhood Services, told council members that the goal of the metal sheeting is to make it so people can still stop and lean against the benches to rest if needed — but only for about five or 10 minutes.

"And then we want them to get a little uncomfortable so you keep moving along, because those areas in the little porticos aren't meant to be a hangout spot, but they've turned into that," Striker said.

Police Capt. Dave Singley said Spokane police had received 218 calls for service on the bridge over the past 12 months: Four assaults. Two fights. Three robberies. One shooting. One stabbing. Thirteen drug calls. Dozens of welfare checks.

City officials are looking to install security cameras, brighter lights and signage encouraging people to report crime in and around the alcoves. Officials also said they've hired a contractor who will add a layer of anti-graffiti coating once the weather is warmer, ideally in time for the Expo 50 celebrations beginning in May.

The Monroe Street Bridge's other major problem — suicide — appears far more intractable.

For decades, the bridge has been a destination for the suicidal, with more than a dozen people dying there. Over the past 12 months, police received 39 suicide-related calls on the bridge.

Advocates have pushed for solutions for years and frequently place impromptu signage on the bridge urging people to seek help. In recent years, the city has unsuccessfully asked the state government to help fund suicide prevention barriers.

POST STREET BRIDGE

LENGTH: 333 feet

OPENING DATE: 1917

RENOVATION COST: $21 million

Like many of Spokane's iconic bridges, the Post Street Bridge began in the late 1800s as a rickety wooden structure that was later replaced with a steel streetcar bridge. In 1917, it was replaced with a concrete structure with arches that mirror those on the Monroe Street Bridge. During construction, a partial collapse sent more than a dozen workers into the river, killing three.

In May 2019, the city closed the Post Street Bridge to vehicular traffic after an analysis found that it couldn't continue to carry heavy weights. Renovation work began in spring 2020.

Construction was planned to be complete in early 2022, but delays have plagued the project. Davis, with the city, says the timing of the pandemic was a big factor, along with staffing shortages, supply issues and other unexpected challenges that arose with the more than a hundred-year-old structure. The repairs have also cost more than expected: Instead of the original estimate of $18.5 million, the current projected cost is about $21 million, Davis says.

But Davis says the long-awaited reopening date is now on the horizon.

"We're working with the contractor to try to get it open late spring," Davis says. "We don't have an exact date yet — there's quite a bit of finishing work to do."

When finished, the bridge will have one northbound lane for vehicle traffic, plus pedestrian and bike routes. It will also serve as a river crossing for the Centennial Trail and reconnect the North Bank with Riverfront Park and downtown. Maintaining the historic look and feel of the bridge and its iconic arches is a priority, Davis says.

In addition to cars, walkers and bikes, the bridge also carries wastewater, the city's polite way of describing sewage. Before the renovations, a massive 54-inch sewer pipe hung under the bridge. Over the course of just 30 hours last spring, city engineers and workers replaced the entire 70-year-old pipe with a new one hidden away underneath the bridge in a more aesthetically appealing location.

"That was really quite a feat," Davis says. "It is now tucked underneath the bridge instead of this rusty thing hanging on the outside."

MAPLE STREET BRIDGE

Height: 125 feetConstruction cost: $6 million ($64 million today)

Opening date: 1958

The Maple Street Bridge crosses over the Peaceful Valley neighborhood to connect the western parts of downtown with Kendall Yards and the West Central neighborhood. Construction began in 1956, making it a relative latecomer to the bridge-building game.

The bridge took more than two years to build and came with a $6 million price tag. To help cover the cost, motorists crossing the bridge had to pay a 10-cent toll. This was later raised to 25 cents before being scrapped in 1990.

The bridge casts long shadows over the Peaceful Valley neighborhood that sits directly beneath it.

When it was first proposed, some residents objected to the bridge as an eyesore. After it opened, complaints about objects falling — and being intentionally thrown — from the bridge became numerous. Residents reported youngsters targeting them with rocks, bottles, water balloons and other objects. The Spokane Daily Chronicle reported on an incident involving a bowling ball crashing through a house, and another involving two dogs being thrown from the bridge and falling to their deaths in the no-longer-peaceful neighborhood.

The Washington Toll Bridge Authority responded to the complaints in 1977 by installing fences on both sides of the bridge to stop people from throwing things. More fencing was added in 1990 — fully enclosing the pedestrian walkway in a chain link cage.

The move was controversial. Several citizens wrote letters to the newspaper arguing that the fence would create hazards if someone needed to exit their car during an emergency. They also noted that it would prevent pedestrians from escaping in the event of an assault.

The fence is still there today. The odds of a bowling ball crashing through someone's house are significantly lower, but the bridge isn't pleasant to cross on foot.

Peaceful Valley residents still deal with issues associated with the bridge. When the city replaced the bridge's deck with a concrete one late this summer, residents below complained of rumbling from machinery and scraping concrete making it impossible to sleep for days on end.

Davis says the city used a specialized concrete that will hold up better than the asphalt that previously covered the bridge, and that it should last another 20 years before needing work.

UNIVERSITY DISTRICT GATEWAY BRIDGE

COST: $15.4 million

HEIGHT: 120 feet

LENGTH: 450 feet

CONSTRUCTION DATE: 2018

One of Spokane's newest bridges is the University District Gateway Bridge, completed in 2019 to provide a pedestrian and cyclist crossing over the railroad tracks in East Spokane.

The bridge unites East Sprague Avenue and the University District, and is distinctly modern, with steel suspension cables and a sleek white color.

Construction began in 2017 with funding from a variety of state and local sources.

The bridge wasn't without controversy. For several years, the proposed bridge was at times derisively referred to as the "Bridge to Hookerville" — an unfortunate nickname coined by George McGrath, a regular City Hall gadfly. The City Council eventually banned the phrase from being used at its meetings, and the nickname faded away.

Steel tariffs delayed construction and sparked controversy between the city and Garco Construction, which built the structure. But after it opened, the bridge was recognized with a national Project of the Year award for transportation from the American Public Works Association.

"This project took more than a decade to become a reality," Marlene Feist, the city's public works director, said in a video announcing the award. "This bridge already has become an iconic feature in our city's urban core and is leading to new investment — everything we had hoped for."

SUNSET BOULEVARD/LATAH BRIDGE

CONSTRUCTION COST: $425,000 ($13.4 million today)

HEIGHT: 64 feet

LENGTH: 1,070 feet

DATE COMPLETED: 1913

ESTIMATED REHABILITATION COST: $65 million

Less than a year after the Monroe Street Bridge was finished in 1911, the city began working on a similarly massive undertaking: the Sunset Boulevard Bridge.

Better known today as the Latah Bridge, the massive concrete arch structure crosses Latah Creek and connects the West Hills neighborhood with the rest of the city. The bridge was built in response to growing demand for infrastructure that could handle automobiles and agriculture imports from Central and Western Washington.

The bridge is shorter in length but taller than the Monroe Street Bridge, making it the second-largest concrete arch bridge to be built in Spokane.

The bridge opened in 1913, with seven dramatic semicircular, or Roman, arches of varying sizes to accommodate the uneven landscape underneath.

Like the Monroe bridge, the Latah Bridge was a feat of engineering. But in recent years, it has started to show its age.

In 2012, a study found that the bridge's main arches were still in good shape, but that parts of the bridge's deck had deteriorated significantly. The city had already reduced traffic from four lanes to two in 2009, and weight limits were added in 2021. Stricter weight limits were implemented this January, restricting large vehicles like garbage trucks, aerial fire trucks and some construction vehicles from crossing it.

Davis says a full rebuild doesn't seem necessary but that significant renovations— similar to what was done to the Monroe Street Bridge 20 years ago — are needed. The city estimates that such improvements will cost $65 million.

The City Council passed a resolution requesting state funding last summer, but City Council President Betsy Wilkerson says state funding seems unlikely anytime soon.

The city is now working on a study that will detail what's needed to fix the bridge and allow the city to apply for a grant through the federal Bridge Investment Program.

Wilkerson says the bridge is a "vital lifeline" that connects the western part of the city with downtown business and institutions of education, and that securing federal funding is a major priority.

"That's a prime opportunity for housing development," Wilkerson says. "But how can you build up there if you can't get to it?"

Wilkerson is optimistic that the city's application for funding will be successful, and notes that bridge repairs are a key part of President Joe Biden's recent infrastructure investments.

The $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill passed in 2021 was celebrated by Biden as a "historic opportunity" to repair the more than 45,000 U.S bridges rated as in "poor" condition. (The Latah Bridge is one of them.) A recent analysis from Transportation for America found that states have spent much of the infrastructure money on bridge and road repairs and highway expansions instead of public transportation.

Even when funding is secured, a fully renovated Latah Bridge is still a long way off.

"The reality is that the earliest construction could start is probably around 2028," Davis says.

THE DOWNTOWN RAILROAD VIADUCTS

In addition to the river, the city of Spokane is also divided by a series of railroad tracks.

The Northern Pacific Railway started building the tracks in 1882 — connecting Minneapolis to Seattle and Portland and driving a wedge through the center of downtown.

The railroads made Spokane a hub for commerce and helped fuel its early 20th-century boom years, but the tracks also proved to be a source of conflict as automobiles began to replace horse-drawn carriages.

Many of the tracks were at the same level as the street, which frequently led to hours-long traffic jams and occasional collisions.

Frustrations came to a head in 1912, when the city passed a law requiring that the railroad tracks be elevated or moved below ground. The Northern Pacific Railway agreed, undertaking a massive project between 1915 and 1917 to raise the railroad tracks above street level through a series of viaducts that define the south edge of downtown to this day.

Some of the viaducts are too short to actually allow modern trucks to pass, which has led to dozens of trucks getting stuck under the tunnels, delaying train traffic for hours. In 2021, the city installed "warning chimes" near the entrance to the Sprague Avenue and Division Street viaduct, which hang from a post and will hit the top of a truck and make a loud noise to warn drivers if the truck is too tall.

In recent years, the city has struggled to respond to homeless camping underneath the viaducts. The city passed a law in 2022 making it an arrestable offense to camp underneath the tracks, but people still do so frequently.

FISH LAKE TRAIL EXTENSION

CONSTRUCTION DATE: Undetermined

The city's days of bridge building aren't over yet.

For years, the city has been working to connect the Fish Lake Trail with the Columbia Plateau Trail, which runs over 130 miles through Eastern Washington.

Since 1991, the city has paved 9 miles of the trail. But a 1-mile gap remains with a major obstacle: two active rail lines.

Crossing the rail lines will require a bridge, but the funding isn't there yet. The city asked the state for $1 million to help fund engineering plans for the bridge in its list of legislative priorities this year, but the draft 2024 budget released by state lawmakers doesn't include that funding.

Wilkerson says the city is going to keep trying.

"It's really important to the environmentalists and people who live in that neighborhood," Wilkerson says. "It's community investment. Everybody will be able to enjoy it." ♦