After a long day working at the Coeur d'Alene Tribal Court, Boots Faletogo comes home on Dec. 15 and puts on KREM TV's 10 pm newscast like she usually does. But that night, she sees a story about the Spokane Police Department hiring four officers from Seattle.

There's Officer Josh Zuray, a former pastor and then Officer Bryan Weber, a trained chef. There's Officer Jesse Cahill, a WSU grad married to a Spokane native. And then there's Jared Keller..."I was like 'Jared Keller... Jared Keller... Jared Keller, I know that freaking name," she says.

"I f—-ing knew it," she says.

She calls her family members.

It was New Year's Eve two years ago. Body camera footage shows what appears to be a routine traffic stop turn into a foot chase as the man the police have pulled over — a 6-foot-2 Samoan named Iosia Faletogo — makes a break for it into traffic. The officers chase him down, Keller tackles him, and there's a frantic scuffle as officers call out the handgun on the ground near Iosia's hands.

"You're going to get f—-ing shot, dude!" Keller yells on the video.

"He's reaching for the—," another officer says

Iosia's last words — "not reaching" — come almost simultaneously as Keller pulls the trigger, his service weapon pointed at Iosia's head. There's a bang. Someone on the video screams before an officer announces, "shots fired, shots fired."

“The family had to pay to get the left side of his face reconstructed so we could have his open-casket funeral,” Boots Faletogo says. "He wasn't even reaching, and he shot him."

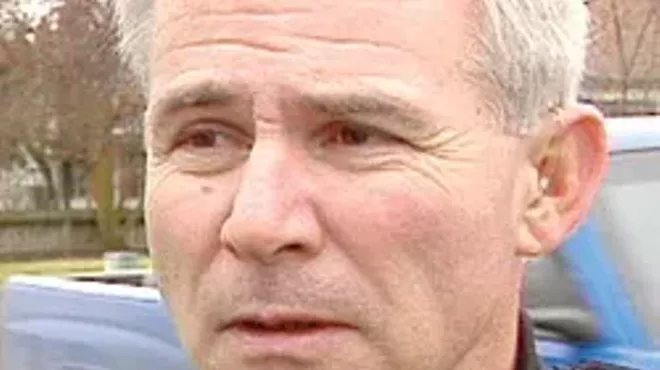

But when Spokane Police Chief Craig Meidl watches the body camera and dashcam footage of the Iosia shooting, he sees it through the lens of a police chief. He notes what appears to him to be Iosia's attempt to grab the gun, and that, in one instance, Iosia appears to grab the top of the barrel.

Several reviews, including a report from the Office of Police Accountability — Seattle's independent oversight agency — came to the same conclusion as Meidl. Keller's decision to kill Iosia was justified by the circumstances.

Pressed on Keller's record by the Inlander, Meidl expressed unwavering confidence in the decision to hire him.

This year, as Seattle has grappled with riots and police brutality protests, more than 110 police officers have departed, transferring to cities like Spokane. Meidl sees a big advantage in hiring officers who've already been trained to handle the metropolitan pace of challenges like homelessness, mental illness and gun violence.

But just as they bring that big-city expertise to Spokane, they also bring with them a piece of Seattle's recent turmoil.

"If I know what this one officer did, what did the other officers do?" Faletogo asks. "We got the Seattle rejects?! What the f—-?"

To Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward, however, recruiting four new officers from Seattle was a simple victory.

"A BIG win for Spokane!" she posted on Facebook, along with a picture of her with the new officers.

Last year, Woodward ran a mayoral campaign based on bashing Seattle and lionizing the police union. She went beyond merely admiring the lurid excoriation of Seattle's permissiveness of homelessness in KOMO's "Seattle is Dying" polemic; she tried to recruit the KOMO reporter to come to witness the problems in Spokane. She ran ads bragging about her Police Guild endorsement and complained that the independent oversight debate about the Spokane's police ombudsman was hampering the union's contract negotiations.

So this year, the day after the Seattle City Council took an initial vote to cut funding for its police department, Woodward turned it into a recruiting pitch.

"IF THIS DESCRIBES YOU, GIVE ME A CALL," Woodward wrote in an Aug. 11 Facebook post laying out a call for new officers, implicitly contrasting Spokane with places like Seattle and Portland.

"Other cities have taken a much swifter, more aggressive approach that has abruptly displaced officers and downsized departments," Woodward says. "To officers who have lost jobs, Spokane has a message for you: we’re hiring."

City of Spokane spokesman Brian Coddington says Woodward wasn't involved in the hiring process and was not aware of the controversy around Keller when she posted her Facebook message.

Though Woodward cited her August recruitment pitch in her post celebrating the new hires, it's not clear exactly how much it played a role in the decision of the four officers to come to Spokane. None of the officers agreed to talk to the Inlander.

While one officer did hear about Woodward's post from a friend who recommended he look at Spokane, Meidl says another of the four started the hiring process with the city back in February, long before either Woodward's Facebook post or the George Floyd protests.

But all four, he says, had existing connections to Spokane, and all four shared a frustration with the vocal anti-police sentiment in Seattle.

"One of them said to me, he would drive down the streets of Seattle and people would literally stop walking on the sidewalk and flip him off," Meidl says.

In July, the department reported that 59 officers had been injured in a single day of protests, battered, burned and cut by rocks, bottles, pieces of wood and explosions.

In August, Seattle's Carmen Best — a Black police chief in a majority white city — resigned in protest to the Seattle City Council's proposed cuts, complaining that they "felt very vindictive and very punitive." (The council later pared back the cuts after a mayoral veto.)

Shaun Scott, a Seattle-based activist and historian who has chronicled more than a century of Seattle police abuses, says the department's problems are self-inflicted wounds.

“It’s no surprise that the Seattle Police Department has had issues with officer retention,” Scott says. “The No. 1 cause for that is the Seattle Police Department.”

“That has been a huge psychic and financial albatross for the Seattle Police Department,” Cross says. “They have only gone down the path, I think, of making life harder for themselves with a number of unjust 'officer-involved shootings' — as the saying goes — of unarmed African-American folks."

In 2016, for example, Seattle Officer Christopher Twiggs wrote in his exit interview that he was going to retire in Spokane, citing his desire to move to a place where the “department and community supports their law enforcement rather than attempting to hem them up for nonsense."

After the conviction of Karl Thompson, the Spokane police officer who repeatedly beat mentally-disabled janitor Otto Zehm, Meidl stood up and saluted Thompson and wrote in an email about how those in the department felt "betrayed by the very public we’ve sworn to protect."

Upon being appointed police chief in 2016, Meidl apologized for the email and met with Zehm's family.

Today, attorney Breean Beggs — who sued the city of Spokane on behalf of the Zehm family — is the City Council president and is playing a key role in Spokane's police reform discussions.

When the Inlander informed Beggs about the controversy around Keller, Beggs let out an exhausted no-rest-for-the-weary chuckle.

While he declines to weigh in on the Iosia shooting specifically, he says that he hopes that the city conducts a legal "risk assessment" of an officer's use of deadly force before hiring them.

Meidl says the hiring process involves "an extremely, rigorous thorough background investigation ... on par with a top-secret clearance.”

He says that a psychologist sends the officers through a battery of six different tests, including a personality test, an implicit bias test, and a polygraph test. He says he was briefed on Keller’s record — two shootings in five years — and took his circumstances into account.

Meidl says the department has actually rejected three requests from Seattle officers to switch to Spokane. Twenty-nine officers from other cities have tried to transfer to Spokane this year, he says, and the police department has accepted fewer than a third of them.

Even now, Meidl says, the department still faces some recruitment hurdles.

"We haven't had a contract in four years," Meidl says, "Our salary is not where a lot of other departments are."

It takes time to train new officers from the ground up, and they can decide to leave at any moment. Three of Spokane's new police hires quit in the last month, Meidl says.

Some quit because they struggle with the pace. One, he says, quit because their spouse was worried about their personal safety.

Those worried their loved ones will be killed because they're cops share a tragic kind of symmetry with those worried their loved ones will be killed by the cops.

"He was a family man," Faletogo says of Iosia. "He would do whatever he could for everybody in his family."

"He was a caring man. He has two children—," Faletogo starts to say before correcting herself. "He had two children."

She wonders whether his race and appearance played into his death.

"He was a big Samoan," Faletogo says. "I think some of why he got shot had to with that."

It's been a rough month. Three weeks ago, she learned that her husband — incarcerated at Airway Heights Corrections Center — had contracted COVID-19. She hasn't told him the man who killed his brother is moving to Spokane.

The Inlander asked Meidl what he would say to Faletogo after hiring the man who shot her brother-in-law. But in a circumstance like this, he suggests, there's no line or statement that can address the depth of their loss.