Throughout his life, Spokane artist Harold Balazs transcended a lot: the challenge of providing for his family through his artwork, the ailments that come from working with concrete, metal and fire, and the "bullshit" of bureaucracy (a word which he immortalized in his 1974 sculpture known as the "Lantern" outside of the INB Performing Arts Center).

In a career spanning seven decades, Balazs produced hundreds of public works throughout Washington, Alaska, Oregon, California, Montana and Idaho, as well as a piece in Westlake, Ohio, where he was born.

"[Balazs'] legacy is spread all over town and what he's left behind, in all the churches and residences and commercial buildings," says fellow artist and longtime friend, Steve Adams, in Planned Chaos, the first episode of Spokane Arts' "Meet the Makers" video series. "To call him a Renaissance man doesn't even cover it; he's so multi-talented in so many different ways and works in so many different materials."

Balazs died at his Mead home Saturday night at age 89, although a final exhibition, I Did It My Way, is set to open next week at The Art Spirit Gallery in Coeur d'Alene. It will mark the end of long and remarkable career of an artist whose legacy looms large over the region.

Up until the past few years, Balazs could still most often be found at Mead Art Works, the shop on the Peone Creek land where he lived for 58 years with wife, Rosemary, and their children and grandchildren. Working. Making art. Creating wonder, as he called it.

No one was exempt from the wonderful world of Balazs, even strangers. Longtime friend, former apprentice and fellow artist Ken Spiering tells this story about Balazs' anonymous generosity when Spiering was traveling to San Francisco:

"Harold handed me a box of a hundred fired ceramic 'coins' about 2 inches in diameter, suggesting that I scatter them in the sand along the beaches. These coins had mysterious writing that could have been ancient Greek, Assyrian, or alien, and 'fossils' of bugs and creatures unlikely to have been of this earth, perhaps though of Middle Earth. This was the fun Harold had with those people he would never know, but felt connected enough to the rest of humanity to entertain them, to help promote wonder in this world."

In 1998, MAC curator Beth Sellars wrote in the exhibition catalog: "Harold Balazs the artist/artisan and Harold Balazs the man shared equal intensity. To know only the artist's work is to miss a large part of what Harold is about."

So if you consider that transcend also means "to surpass," Balazs did just that in his life and his art, the two being nearly inseparable. When pestered during an interview about the meaning of his work, an irritated Balazs told a reporter: "My art means food for my family," relays Tom Kundig, a family friend and owner/principal at Seattle-based design company Olson Kundig.

Balazs impacted the arts community, locally and beyond. He supported Mead School District's Eye4Art fundraiser, for example. He advocated for "percent for art" legislation — less than 1 percent of public funds dedicated to art for publicly funded buildings — which has infused art into communities throughout Washington and Alaska, as well as paved the way for similar initiatives elsewhere.

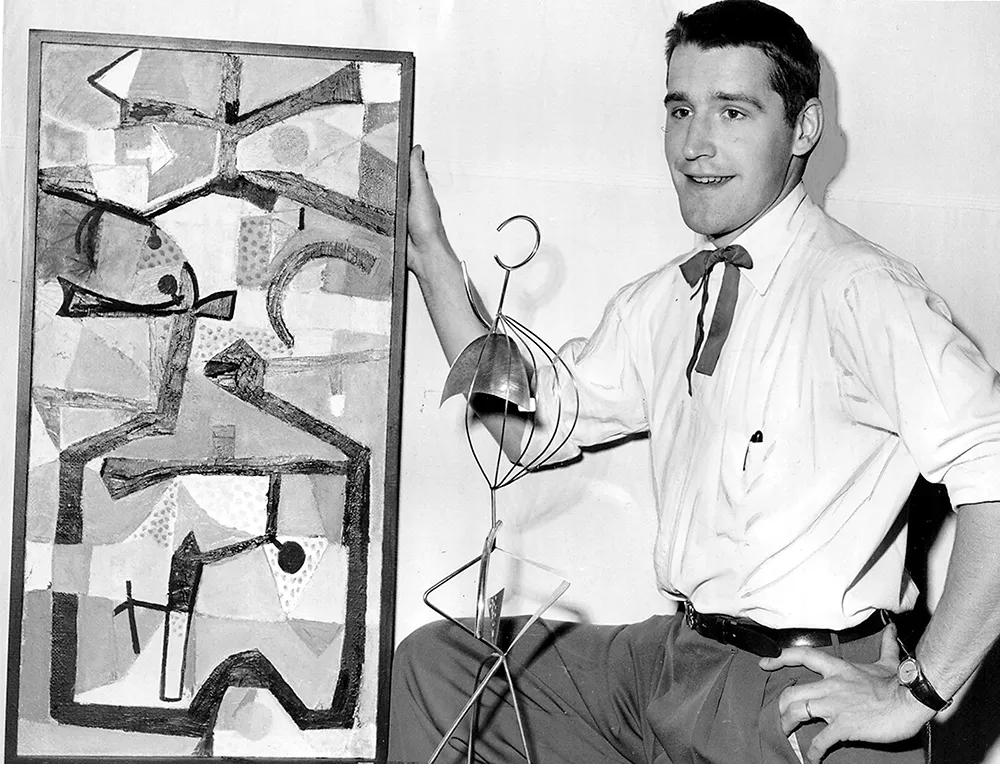

Although he somewhat eschewed institutional education, Balazs, by all accounts, was an outstanding instructor. His physical presence — tall, with piercing eyes, a squared jaw and a shock of hair gone whiter well ahead of his perpetual mustache — combined with his sense of humor, content knowledge, and delight in sharing made for a dynamic delivery.

Balazs' workshops "were spellbinding orations in themselves and you became mesmerized by the development of an idea through gestures and words and a joke, or his knowledge of art history or contemporary issues," wrote the late Rudy Autio in Art is an Art Form. Autio, who earned national recognition as a ceramicist, including as the first artist-in-residence at the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts, was Balazs' classmate at Washington State College.

Many artists whom Balazs mentored are mentors themselves, like Spiering, an art teacher at Freeman High School, whose public works include the oversized Radio Flyer ("The Childhood Express") in Riverfront Park.

"Fifty years ago as a student," recalls Spiering, "I met Harold 'schussing' from on top of a desk in the art room at Gonzaga University, demonstrating his method of skiing a mountain — straight ahead without reservation." Spiering was struck by how Balazs "filled the room, not with ego, but with his enthusiasm at being alive and with a need to share that with those around him."

"Harold had stories nonstop," adds artist Allen Dodge, "a sort of currency that he'd developed, like his calligraphic sort of art-language that is so recognizable as 'a Balazs.'" Dodge's favorite story recalls Balazs "stalking through the woods with a big butcher knife and a bag, madly, gleefully harvesting these succulent [wild mushrooms], laughing like a mad man. Pure joy."

Dodge and his wife, Mary Dee, credit Balazs with steering Allen toward more metalworking and both artists toward enamel. "Being near Harold, you are treated as a contemporary, a friend and a co-conspirator in art," says Dodge, who worked with Balazs on a 2007 commemorative piece for the late Pat Flammia, an artist who helped create Coeur d'Alene's Art on the Green festival and one of Balazs' earliest collaborators from 1951.

Balazs' deepest influence, says Dodge, "has been on the artists and architects and planners in our community who heard him and understood his insistence that art is important, that it is vital to a place, be it home, city, state or country."

When Allen says Balazs, he means Rosemary too. "The art and the life they have lived couldn't have been possible had they not worked together; he madly spinning out artwork, she calmly keeping all feet on the ground and the household running, not to mention her work grinding, pounding, pouring concrete in the shop, etc."

Kundig, an architect who worked for and with Balazs at several stages in his life, shares a story about Balazs gleefully hurling down the ski slopes in "terrible form but faster than heck," with kids following him, maybe recognizing Balazs was of their tribe.

"Everyone calls [Balazs] a 'force of nature,' and of course he really was, and his influence just is multi-generational," says Kundig, whose father, Moritz Kundig, met Balazs in the '50s while skiing. The senior Kundig, an architect and designer of the Unitarian Church and Spokane Civic Theatre, was part of a cadre of modernists who helped define Spokane's cityscape, and Balazs fell right in with them.

Balazs' work ethic, ingenuity and understanding of the building process earned respect from builders and architects alike, Kundig included. In 1966 the American Institute of Architects, for example, awarded Balazs a gold medal for craftsmanship, while the Joel E. Ferris house, for which Balazs did interior metalwork, garnered another AIA gold medal for the architectural team. In 2001, Balazs was included in Seven Living Treasures of American Craft by the Northwest Designer Craftsmen and has two works in the venerable Smithsonian American Art Museum.

"Harold didn't distinguish between art and architecture," says Kundig, who credits Balazs with inspiring his love of steel, the mechanics of design, and to believe in himself despite any forces to the contrary. Also, says Kundig, "I learned how to work hard."

One needn't have worked for Balazs to experience a connection with his wide assortment of artworks, especially locally. Since 1951, Harold's artworks have been in, on or near numerous schools, banks, private and public spaces, and houses of worship. Before it was stolen in 1997, "Sacajawea" resided at Eastern Washington University, while all who entered St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church would have opened doors covered in Balazs' vibrant enamel-work. A cast-stucco tree graces the exterior of Hennessey Smith Funeral Home, and the Rotary Fountain at Riverfront Park is a 24-feet high, gleaming-metal pavilion where children splash and squeal in the water.

Balazs forged strong ties in other communities as well. In Coeur d'Alene, he was an early supporter of The Art Spirit Gallery and its founder, the late Steve Gibbs. He exhibited there since 1997, contributing to the gallery's growing reputation for contemporary art.

"Throughout Harold and Rosemary's life together, Harold has been the gregarious public personality touching the lives of so many people," says Beth Sellars, the MAC curator. "Rosemary however has been the quiet support behind Harold's every waking hour. She is Harold's backdrop, his solid rock upon whom he has depended for nurturing all things in his life."

Sellars met Balazs in 1975, when she was installing his watercolors for an exhibition at the Boise Gallery of Art, for which she served as assistant director. They stayed in touch and in 1985, when Sellars was curator at the MAC, Balazs rallied Steve Adams to participate in an outdoor festival that would become ArtFest, one of the museum's significant fundraisers and a favorite Browne's Addition summer event, now in its 32nd year.

Ali Shute remembers being excited to meet Balazs at ArtFest and purchased one of his works. She didn't have cash and Balazs didn't take credit, says Shute, who now runs Coeur d'Alene-based Arts & Culture Alliance, but he let her have the work if she promised to pay him later. She was stunned.

"Harold is the most generous guy I know," says longtime friend and fellow artist Mel McCuddin, who met Balazs in the mid-'50s at the Corbin Art Center. McCuddin's earliest impression of Balazs was of how devoted he was to making a living with his art, especially his enamel jewelry and other items he sold through the former furnishings store, Joel. He sometimes wondered if Balazs might have had an easier time living elsewhere.

"He felt about New York like I do; you could get swallowed up by it," says McCuddin, who was 80 when he and 85-year-old Balazs exhibited together at The Art Spirit Gallery. Even though they shared a profession, they bonded more over the outdoors — hunting, fishing — and family, all of which provided necessary fuel for Harold's larger-than-life appetite. "He's going to leave a big hole," McCuddin says.

Balazs was not religious per se, adds Spiering, who notes how well-read Balazs was in religion and related subjects. "Harold had respect for worshippers in those faiths he did work for, and the thoughtfulness in meeting the needs and superseding the expectations of his clients was paramount in his work."

Kundig thinks Balazs was a very spiritual person, even as he wonders which word Balazs would have used. "His effect and his influence was the support of the creative spirit and everybody's creative spirit, not just his own." ♦

Harold Balazs: I Did It My Way • Jan. 12-Feb. 3 • Opening reception Jan. 12 from 5-8 pm • Art Spirit Gallery, 415 Sherman Ave., Coeur d'Alene • theartspiritgallery.com