For nearly eight years, they've clashed — sometimes publicly, sometimes privately, sometimes through intermediaries — but the irony is this: The political future of City Council President Ben Stuckart has been lashed to the legacy of Mayor David Condon.

As more conservative mayoral candidates like Nadine Woodward attack the liberal Stuckart for the status quo in the city of Spokane, they implicitly call the conservative mayor's record into question.

"We've seen the crime rate go up and the homeless issue get worse downtown over the last — I'd say exponentially — in the last two or three years," Woodward says. "People are frustrated. People who work downtown are frustrated. ... People who own businesses downtown. People who visit downtown. People who say they don't feel downtown is safe."

But Stuckart?

He defends the results of the last seven and a half years, arguing crime has decreased downtown and across the city.

"We're much safer. The downtown is much more vibrant, has more activity. We're revitalizing neighborhoods," Stuckart says. "And we have more police officers on the street ... Since we've been in office, public trust in the Police Department has gone up."

The stats, meanwhile, are messy enough that almost any candidate can choose the data points he or she prefers.

Condon passed up on the chance to talk to the Inlander about his public safety record. But this week, he sent out a press release stressing that, "both the City Council and administration have been committed to working together in order to foster a safer downtown."

At times Condon and Stuckart have disagreed over public safety. Condon, like Woodward, didn't support Stuckart's tax hike raising money for more police officers this year. But in general, the record of one is difficult to entangle from the record of the other.

As the mayoral race heats up, there are a couple key questions: Are we safer than we were eight years ago? And if not, who deserves the blame?

Police Chief Craig Meidl doesn't have any doubt. This year, at least, reported crime has decreased.

"I think the key word's gonna be 'reported' — and I say that to acknowledge those people who feel like crime isn't down — but the reported crime is unequivocally down," Meidl says.

But Meidl, as much as anyone, knows the challenges of relying on crime stats.

The messiness of crime stats is a gift to politicians and pundits everywhere: It lets them preach the figures that fit their narrative as gospel, while brushing off the stats that don't as too flawed to be reliable.

So when Woodward laments that "downtown commercial burglaries are up 35 percent so far" in 2019, she leaves out the fact that, compared to this time last year downtown, rape is down 35 percent, commercial robbery is down 50 percent, personal robbery is down 5 percent, domestic-violence aggravated assault is down 54 percent, non DV-aggravated assault is down 26 percent, residential burglary is down 35 percent percent, larceny is down 19 percent and vehicle theft is down 12 percent.

And yet, when Stuckart points to the drop in crime downtown this year, he leaves out the fact that the stats show violent crime spiking the year before — and that violent crime downtown is merely subsiding back to its 2017 level.

Focusing on only two and a half years of crime in a single precinct is rife with problems — particularly because the comparatively small size of downtown can make small shifts seem like seismic ones. Go from two commercial burglaries to eight and you've suddenly got 300 percent more increase.

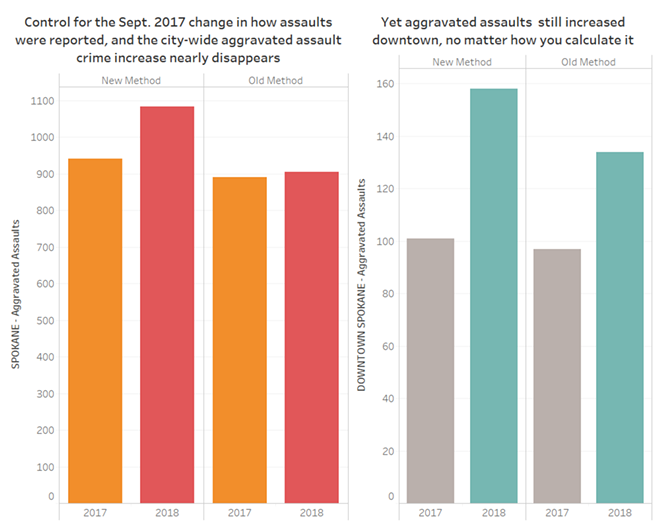

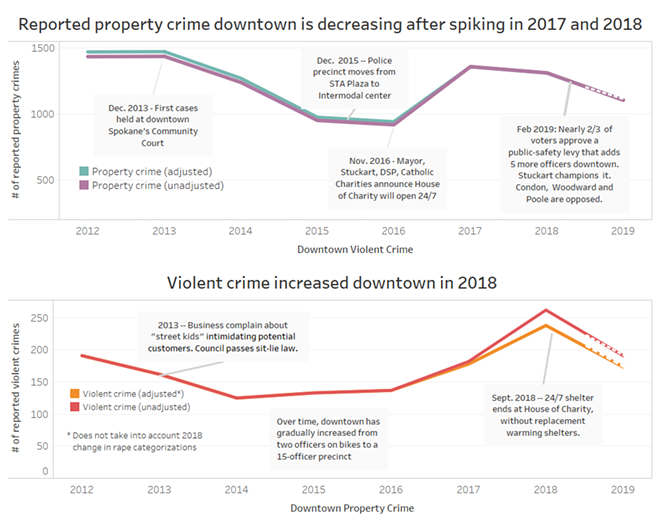

But the bigger problem is that, in the three previous years, the Police Department made some drastic changes to the way crime stats were reported to the federal government and displayed to the public. A change in October 2016 likely resulted in a bit more property crime being showcased in the statistics. A change in September 2017 made it look like the city had a sudden 15 percent spike in aggravated assaults last year, when, in truth, there was only a minor bump citywide. A change in 2018 had a similar impact on rape figures. (Scroll down to the bottom of this post for a more detailed explanation.)

That doesn't mean the stats can't tell you anything. Taking into account these caveats, you can still see a few things. There legitimately was a spike in violent crime downtown, though the increase wasn't exponential. Fewer property crimes are being reported citywide than there were a few years ago. But during the era of Condon and Stuckart, the change hasn't been dramatic over the long term in either direction. In the past eight years, Spokane hasn't turned into either idyllic Mayberry, USA, or dystopic Snake Plissken-era New York.

When it comes to violent crime, mayoral candidates Shawn Poole and Kelly Cruz say Spokane might be safer. But they're highly skeptical of the claims that property crime has fallen.

"Property crime in my opinion is not down," Poole says. "People are just not calling Crime Check anymore because Crime Check does nothing... You can skew the numbers and massage numbers all you want, or all someone else wants. However, property crime is continuing to rise, it has risen."

He says he's spoken with people who have been victimized, call Crime Check, but a cop never comes to their door. And so when they're victimized again, they don't even bother calling. Cruz says he's heard the same thing.

And while Councilwoman Lori Kinnear celebrates the apparent decrease in property crime the last few years, Councilwoman Karen Stratton echoes the concerns of Poole and Cruz.

There’s an old cop joke, says Spokane Police Sgt. Terry Preuninger. “If you want to reduce crime, stop answering your phone.” A better, more responsive police department can actually cause crime to appear to go up, he points out.

Meidl says that's the case no matter what community you go to.

"I just saw this statistic a couple weeks ago, nationwide, only about 40 percent of property crime gets reported," Meidl says. "That's not unique to Spokane. That is a nationwide figure."

"I really do think crime is going down," Meidl says. "I also know, though, that there are a lot of frustrated people out there that have been victimized and I don't want to take anything away from those who have been victimized."

Even those who truly believe crime is down, like City Councilman Breean Beggs, argue that Spokane has a reputation problem.

"I think overall, yes, we are safer," mayoral candidate Jonathan Bingle says, crediting the mayor, the City Council and Meidl for the reduction. "I don’t think the perception of the city is that we’re safer. Perception matters. While we may be safer, people don’t feel safer."

And that includes Bingle and his family.

But even downtown, there's debate about what's exactly happening. Mark Richard, chair of the Downtown Spokane Partnership, can point to numerous businesses that have had serious struggles with the climate downtown. Talk to the businesses, he says, who have concerns for the safety of their employees. Notice how many of them have added locks to their bathrooms.

But Richard also remembers the controversy around large groups of "street kids" harassing downtown patrons in 2013. The outward behavior of people loitering around today, he says, isn't "as intimidating or offensive or aggressive as what we were seeing in 2013."

The challenge today is a different one.

"What we have seen is we've seen this rise in folks that exhibit behavior that is consistent with people that are suffering from addiction of serious narcotics and opioids," Richard says.

Asked if we're safer than eight years ago, Richard pauses to think about it.

"I don't think so," Richard says. "I don't think so. I would say if you asked your average citizen they would say, 'I don't feel safer.'"

But later Richard sends a text message, stressing that his security supervisor disagrees.

"I have to trust his instincts," Richard says. "He believes it is safer downtown today than it was in 2011."

A lot of things that might make people feel unsafe downtown, Meidl stresses, aren't actually against the law.

"It's not illegal to walk around downtown with a machete in your hand," Meidl says. "It's not illegal to yell at a stop sign, it's not illegal to have a yelling match with somebody that nobody else can see. But it's very concerning."

Now compound that with Facebook pages like Tweaker Blast that widely share these kinds of incidents as evidence of urban decay.

"With social media, with Facebook, with Twitter, with Snapchat with the Nextdoor app, one of the things we're seeing is one incident will be sent out on social media and shared 10, 15, 20 times," Meidl says.

The more crime you see, the more dangerous things can appear. That's not to say that Meidl thinks everything is hunk-dory. Police keep continually rearresting the same repeat offenders, responsible for the crime increase, he says, and they keep getting out.

"I don't feel like we're celebrating the crime reduction," Meidl says. "I think we're still struggling: How do we keep these chronic offenders off the street?"

If you want to blame — or credit — both Stuckart and Condon for the state of crime in Spokane, it's easy. Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich, for example, blames recent problems on the lack of space in the county jail. Both the mayor and the council president, he says, have opposed a new county jail for years.

With the jail packed, Knezovich says, dangerous criminals are being booked and then dumped right back on the street. "We have more people out there carrying guns and committing crime than we have had in a very long time," he says.

What becomes trickier is when you want to blame one but not the other. When Stuckart and Condon both announced support for building a separate city-owned jail for misdemeanor crimes last month, for example, Woodward praised Condon's support for the idea, but slammed Stuckart's support as a "red herring" that distracted from the debate over the county facility. (According to the Spokesman-Review, Woodward declined to take a position on either facility.)

Do you blame Condon for moving the downtown Spokane police precinct to the Intermodal Center over Stuckart's objections, or blame Stuckart for being agnostic on moving it back? Do you credit Condon's administration for getting the grant-funded partnership between police officers and mental health specialists, or credit Stuckart for passing a levy, over Condon's objections, to ensure those positions continue to be funded?

Both the City Council and the Mayor's Office, year after year, tried to get the Legislature to change one of the biggest factors driving Washington state's sky-high crime rate: the fact that Washington state was the sole state that essentially had no supervision program from property offenders. And this year, thanks to their lobbying, the Legislature finally passed a law to try to address that problem — at least for car thieves.

That's not to say that Condon and Stuckart have always agreed on public safety. More than once, Stuckart has pushed for more police officers than Condon was willing to pay for.

Facing a Recession-era-budget deficit in their first year in office together, Stuckart voted against Condon's budget, in part because it cut 19 vacant police officer positions. And in their last year in office together, Stuckart championed a $5.8 million property tax increase to pay for 20 more police officers and save firefighter jobs, while Condon opposed it. Woodward says she welcomes those officers.

"With the latest public safety bond, we're going to get some new officers. In fact, five of those officers will be located downtown with a sergeant," Woodward told KREM last month. "So that's a good thing."

But in her interview with the Inlander last month, Woodward said that she voted against the levy that paid for those officers. (She declined to reveal other aspects of her voting records, including how she voted in the presidential election, the library bond or the school district, stressing that it was a secret ballot.)

With the addition of the 20 new officers from the public safety levy, Stuckart says the city has added a total of 72 new police officers.

Cruz and Bingle say they voted for the levy. But Poole, like Woodward, voted against it, despite the chance more of his firefighter colleagues might have lost their jobs had the levy failed.

Both Woodward and Poole have maintained that the money could have been found in the budget elsewhere, but neither pointed to exactly where. Poole suggested the city should look, in general, to the waste departments were generating in overtime expenses. He wants to cut the city budgets across the board.

"I would probably look at something like 5 or 10 percent in every department, even the Police Department," Poole says.

Both Poole and Woodward want more police officers patrolling on foot downtown, but don't want to raise taxes to do it. "There's ways to pay for city resources without taxing people again," Poole says.

Woodward stressed that, with such a large budget, there must be somewhere the money for more police officers could have come from.

On one hand, the levy's $5.8 million is dwarfed by a city budget of nearly $1 billion. On the other, the levy generates $1.3 million more than all the city's general fund money spent on homelessness combined.

"It's actually impossible to find that money without cutting entire departments," Stuckart says. Economic growth alone, he says, wouldn't be able to pay for the new officers and save the firefighter jobs.

In her Inlander interview, Woodward says there wasn't just one thing to blame for crime, homelessness and trouble downtown, but pointed her finger at the City Council.

"The City Council just can't get a handle on how to address homelessness, and I don't think the answer is dumping rocks under an overpass, handing out free bus passes or chaining yourself up with somebody," Woodward says. "The City Council, under Ben Stuckart's leadership, were the ones directing all of their — they're the ones that wanted to build 24/7 shelters. They're the ones who are more into enabling our situation."

Yet these examples showcase how intertwined Condon and Stuckart have been.

The City Council supported putting rocks under the freeway to dislodge a homeless camp — but the idea had come from Condon's city staff and the decision was celebrated in a city video created by one of Nadine Woodward's former KXLY colleagues. The bus pass proposal came from the City Council, but Condon supported it as a pilot program. Only one City Council member — Kate Burke — chained herself up outside City Hall in protest of the city's sit-lie policy. Burke has criticized Stuckart for supporting the sit-lie policy.

"You can blame me," says Jonathan Mallahan, Condon’s former division director of neighborhood and business services. "I would have done it all again, even knowing what didn't work about the model. There wasn't a lot of solutions that could be put in place then."

The 24/7 shelters were supported by a wide coalition, including the City Council, Catholic Charities and the Downtown Spokane Partnership. And in his 2018 state-of-the-city speech, Condon specifically celebrated the city's increased investment in 24/7.

In a statement this week, Condon stressed that "a person experiencing the crisis of homelessness is not a criminal, and we will continue to invest in resources to ensure citizens experiencing housing instability have resources available."

Woodward stresses at least one point of disagreement between Stuckart and Condon.

"[The City Council were] the ones who at one point were talking about opening up City Hall to the homeless during the day," Woodward says. "Mayor Condon didn't want the homeless people in the lobby of City Hall. ... That's something that they were considering doing."

But even there, Stuckart and Condon's messy positions are closer than it may sound. Last year, for a brief period of time, the Condon administration put a 30-minute time limit on hanging out in City Hall — but later lifted that time limit, allowing anyone to stay in the City Hall lobby as long they weren't being disruptive.

Stuckart voted for a Burke-sponsored ordinance that reaffirmed that City Hall was open for all, stressing that it did not, in fact, attempt to turn City Hall into a homeless shelter. But when Condon vetoed the ordinance — stressing that City Hall already was open to the public, so the ordinance was redundant and that he didn't want to suggest that City Hall was meant as a homeless shelter — Stuckart declined to override the veto.

"It doesn't do anything," Stuckart says of Burke's ordinance, one he had voted for. "And so then it's posturing."

Today, under the Condon administration's current policy, the lobby of City Hall actually is open to homeless people, and everyone else. Asked if it was a mistake to lift the time limit, Woodward says she isn't sure. She also declined to say whether she'd reinstitute that time limit if she were elected mayor.

"I'm not gonna promise anything. Right now people want me to promise all kinds of things. 'What are you going to do in your first 100 days?'" Woodward says. "How about we just give [the next mayor] the job first."

Spokane County's Crime Check went away from 2005 to 2008 — causing crime to appear to drop during that period, because it was harder to report. The federal definition of "rape" expanded in 2013. The way that Spokane and other cities reported crime to the feds changed in 2016. In the old system, they'd generally only report the most serious crime involved in any given incident. If someone breaks into someone's house, steals the TV and then murders the homeowner, it was only counted as a "homicide," and not a burglary or robbery. The new system that SPD transitioned to is called the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), and it counts each of those crimes separately. While FBI data suggests violent crime stats are only slightly impacted by the new methodology, property crimes like "vehicle thefts" see a 2.7 percent bump, just from switching to the new methodology.

But even looking at the last few years comes with a huge problem. In September 2017, the Spokane Police Department discovered it had been systematically undercounting aggravated assaults — incorrectly categorizing some misdemeanor assaults with weapons as "simple" instead of aggravated assaults.

When local law enforcement switched to the new policy, however, there was the occasional absurdity.

"One of our 'ag assaults' resulted from a snowball being thrown at somebody," Sheriff Knezovich says. Not an iceball. A snowball. "That’s ridiculous."

In mid-2018, meanwhile, the Police Department realized the consultant it had been using to tabulate data wasn't properly including a number of rape allegations in its crime stats; so, when they started including them again, it appeared like there was a massive increase, even though the total number of rape reports had actually fallen.

Remember: CompStat system or the city's FBI-reported crime totals don't include many of the less serious crimes in the totals. Last year, the Police Department had more than 4,000 reports of simple assault, 6,000 reports of destruction of property, 2,600 reported fraud offenses, and over a thousand reported drug/narcotic offenses. But none of those show up in the stats.

So, with all those caveats, does that mean we can't look at crime stats at all? Not at all. But we have to make sure we're taking everything into account.

Take a look at aggravated assaults, for example. Compare the stats for 2017 to 2018, and it looks like they jumped city-wide for 15 percent. But that's almost entirely due to the city switching methodology for how it categorizes assaults. In fact, if you look at all assaults, both simple and aggravated, Spokane Police Maj. Eric Olsen says, the number actually decreased in 2018.

But not everywhere. In downtown, the increase in violent crime last year was real — the problems downtown bumped up the crime rate citywide.

Here's what the downtown crime rate looks like when you adjust for the change in aggravated assault calculations. (Click to make the graphs larger and the text more readable.)

And here's a crude graph that plots how the crime rate in Spokane over the last decade, with the aggravated assault changes and the switch to the NIBRS system taken into account.