In February, U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers surprised nearly everyone by announcing her retirement. For the first time in 20 years, she would not run to represent Washington's 5th Congressional District. With a newly open seat, the race was on.

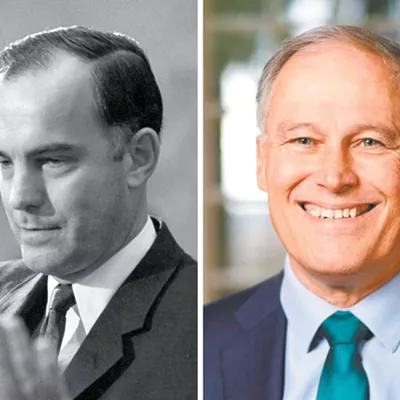

The two people running to take her seat and represent Eastern Washington in Congress don't have a lot in common.

Michael Baumgartner is a Republican. Carmela Conroy is a Democrat. On issues like abortion, the southern border and the economy, the two are firmly split along party lines.

But there's one thing in their backgrounds that unites them: foreign service.

Before entering politics, Baumgartner worked for the U.S. State Department in Baghdad during the Iraq War. He also worked as a counternarcotics adviser to the U.S. government in Afghanistan.

Conroy also worked for the State Department. She spent nearly two decades as a foreign service officer, serving as a regional refugee coordinator in the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan; a political-military affairs officer in Tokyo, Japan; and a political-economic counselor in Oslo, Norway.

Both candidates say their time overseas helped inform their thinking on foreign policy.

"It's not every day you get two former State Department officers running for Congress," Baumgartner says.

"We were all working on behalf of the country," Conroy says. "The two parties had different ideas about the best way to achieve those goals, but the goals were the same."

MICHAEL BAUMGARTNER

Baumgartner grew up in Pullman, the child of a kindergarten teacher and a forestry professor.His parents didn't talk much about politics, but he says they still had a "real sense of service about them" that inspired him to get involved in helping people. After graduating from Washington State University with a major in economics, he spent a year volunteering with the Jesuits working with war refugees in Mozambique.

It was there that Baumgartner started to become interested in economic development — basically "how you make poor countries less poor," he says. He decided to study the topic at Harvard.

By that point, Baumgartner's politics were leaning conservative. During a GOP debate earlier this summer, Baumgartner told his fellow Republicans that he sometimes felt like an outsider at the predominantly liberal institution.

"There weren't many of us, which I think gave us a better conservative education," Baumgartner said. "Because we had to defend our views all the time."

IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN

Baumgartner had planned to return to Africa after Harvard. Then 9/11 happened. It inspired him to go to the Middle East, where he spent time doing economic development work for the United Arab Emirates government in Dubai."They wanted to turn Dubai into the next Singapore," Baumgartner says. "Given the challenges of that region after 9/11, I thought that would be really interesting."

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan ramped up, Baumgartner says he felt compelled to help.

"It gnawed at me that a lot of other Americans were going," Baumgartner says. "Many members of my family had served their country overseas, and I decided, 'Yeah, I should go.'"

Baumgartner left the private sector and took a job as a U.S. State Department Officer at the embassy in Baghdad. He did counterinsurgency work during the 2007 troop surge.

By that point, the Iraq War was deeply unpopular. Former President George W. Bush was facing widespread criticism for leading the American people into an unwinnable quagmire.

Baumgartner took a slightly more optimistic view.

"There was a lot of criticism about the American military," Baumgartner says. "What I saw from American troops was they were doing amazing, hard work in very challenging circumstances."

Baumgartner started writing a monthly email talking about what he was seeing in Iraq. He caught the eye of a Boston Globe columnist, who wrote an article in 2008 describing Baumgartner as a "vision of hope" for Iraq — praising his optimistic outlook as an alternative to the more cynical atmosphere of the time.

"His view of what needs to be done in Iraq was jarringly clear-minded and forward-thinking, removed from the never-ending discussion of how we got into this mess," the columnist wrote.

In 2008, Baumgartner left Iraq and began working as a civilian contract adviser in Afghanistan doing counternarcotics work as part of a program funded by the U.S. government. He was stationed in the troubled and dangerous Helmand Province. It's there that he met his wife, Eleanor, who was also doing counternarcotics work in the area.

ELECTED OFFICE

Shortly after leaving Afghanistan and returning to Eastern Washington in 2009, Baumgartner was approached by a group of Republicans who were trying to recruit someone to run against incumbent state Sen. Chris Marr, who represented the 6th Legislative District covering northwest Spokane County.Baumgartner says the Republicans had approached 35 other people before coming to him.

"I was guy 36," Baumgartner says. "I said, 'Hey, this sounds like a fun adventure.' ... I just really enjoy being part of something bigger than myself."

The race became the most expensive legislative race in state history (at that time). Baumgartner won with 54% of the vote.

Baumgartner spent two terms in the state Senate. His proudest accomplishment? Sponsoring the Senate bill that brought the WSU medical school to Spokane.

Baumgartner left the Senate in 2018 and has since served as Spokane's elected county treasurer. He decided to run for Congress shortly after McMorris Rodgers announced her retirement.

"One thing I didn't get to do in the state Legislature was have an impact on foreign policy," Baumgartner says. "That has a real interest to me as well."

AMERICA ABROAD

Reflecting on his time in Iraq and Afghanistan, Baumgartner says the Bush-era effort to tackle terrorism by spreading democracy in the Middle East was a "noble effort" that was also "ill-conceived." There was justified criticism, he says, but America could still "be proud of its intent."Baumgartner thinks the State Department needs to be reformed to be "more expeditionary."

"I don't believe we can be isolationists, but we also can't be the world's policemen," Baumgartner says. "I have a real interest in trying to create a smarter American foreign policy overseas, because we have to do better than what we did in Afghanistan. It's also just naive to think that we can come home and be isolationists and won't have a lot of challenges on the world's doorsteps."

During a June debate, Baumgartner said he disagreed with calls to put conditions on U.S. military aid to Israel in light of mounting international condemnation over the civilian death toll in Gaza.

"It is in the U.S. national interest to support Israel and root out the Hamas terrorist network," Baumgartner said.

On Ukraine, Baumgartner has said that he supports additional funding to help the country and that it's important that Vladimir Putin does not succeed.

CARMELA CONROY

Conroy spent her early years in Spokane's Hillyard neighborhood in a small house behind the Rogers High School football field. After first grade, her family moved to Spokane Valley, which was still very agricultural in the late 1960s and '70s.No one in her family had gone to college. Her mother worked for an insurance company and her father worked on the railroads. But by the end of middle school, Conroy knew she not only wanted to go to college, she wanted to go to graduate school.

"I started debate club in eighth grade and found out that there were people who got paid to dress up and talk and they called those people lawyers," she says. "And I'm like, 'That's for me.'"

She went to the University of Washington for an undergraduate education, but without much of a clue what to study. Even though she had never imagined living outside of Washington, she decided to take a chance on UW's Japanese program.

"In the late '70s and early '80s, all anybody was talking about was the Japanese economic miracle," she says. "I thought that as long as I was at the University of Washington and Japan was so high on the radar, I should take advantage of their Japanese language program, which is one of the oldest Japanese language programs in the country."

She also took a class from the school of foreign affairs. She was hooked. She dove headfirst into a field she hadn't known existed a few months before.

Then, halfway through her studies, the head of the Japanese program changed. The teaching methodology was turned upside down, and Conroy's grades plummeted. She decided something had to change.

"When I graduated, I was broke and I was sick of school and I could not speak this language I'd been banging my head against for two years," she says. "So I told anybody that I thought could help me that I was looking for work in Japan."

DEPUTY PROSECUTOR

Conroy did eventually find work in Tokyo, running an English program at an elite private school. But once she had saved enough money, she went back to UW for law school.Conroy's first job as a lawyer was back in Tokyo working for Nissan. But it still wasn't exactly what she wanted to do, so she returned home.

"I moved back into my parents' basement, literally as well as proverbially, and started looking for other work," she says.

A friend of her father's introduced her to someone in the Spokane County Prosecutor's Office. She was hired and quickly assigned her first jury trial on her seventh day in the office.

"I was getting paid to dress up and talk, and I won my first jury trial, thanks to the trooper — it was a state patrol trooper who was my chief witness," she says. "If it hadn't been for him, it would have gone a different way."

Conroy worked as a deputy prosecutor for four years. Her experience in the courtroom informs her sympathy for the police and the critical need for funding for the entire criminal justice system.

"Everybody in that system, not just the police, needs to be funded," she says. "Unless all you want law enforcement to be able to do is visit some instant karma on somebody who's done something wrong or is at the wrong place at the wrong time, the whole system needs to be built out. That includes things like addiction treatment and behavioral health and mental health treatment."

VISION FOR AMERICA

Conroy was finally doing what she'd dreamed of as a kid. But the international travel bug had bitten her bad. She was fascinated with the world beyond American borders. So she became a foreign service officer with the U.S. State Department in 1996. Her first post was in Auckland, New Zealand, processing visas."It helped me understand for the first time what people's vision was for what was possible in the United States and how precious it was to be born an American," she says. "[Also,] understanding how important it was for securing our borders by screening people carefully far away from our borders."

In New Zealand, most of the visa applications she saw were from non-Kiwis trying to enter the United States. Conroy says she sympathized with people wanting to visit America, but she was also responsible for maintaining safe, healthy borders. Both of those realities should be priorities for both parties, she says.

"I really wish that the bipartisan bill that was largely drafted by [Republican] Sen. Lankford of Oklahoma had passed," she says. "I'm shocked that the Republican members of the House and Senate would refuse to let that go forward to fund and staff border security because of the Republican presidential candidate's demand that they not — that he would rather run on a problem than secure our southern border. I think that's shocking and shameful."

DIFFERENT DIRECTIONS

Conroy's next post took her back to Tokyo in 1998. There, she met U.S. Ambassador Tom Foley, a Spokane native who had also served as a Spokane County deputy prosecutor before being elected the representative for Washington's 5th Congressional District in 1964 and eventually becoming speaker of the House from 1989 to 1995. They bonded over shared experiences."He said he sometimes missed being a deputy prosecutor because it was the most powerful job that he'd ever had," she says. "This is the U.S. ambassador ... to Japan and the former speaker of the House of Representatives. He said, 'A deputy prosecuting attorney is sent into that courtroom and has to make snap second decisions that'll affect people for the rest of their lives.'"

During nearly two decades with the State Department, Conroy also served in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Norway.

"I worked for Democratic as well as Republican administrations, and what I experienced for most of my career was that there was always something to do that I could throw my heart into," she says.

Throughout her time as an apolitical public servant, Conroy says she believed that both parties were working toward the same goals and national interests. But now, she's running for Congress because she's changed her mind.

"I no longer believe that about the leadership of the Republican Party," she says. "The disinformation, the lying and frankly the idea that a political party should be directed towards the glorification of a specific party leader rather than the promotion of American interests... I no longer believe that both parties are pointed in the same direction." ♦