As the video starts, a dozen or so 40 to 50-year-old men — dressed in red Make America Great Again hats and an assortment of black and gold polos and camo — walk through downtown Spokane, capturing their Saturday night out as "Proud Boys."

On the bar crawl for the local chapter of the national right-wing men's group, they talk about "libtards" and "triggering" people who disagree with their less than politically correct views. They specifically choose to hit up some of the city's most popular alternative nightlife spots, places with "All Are Welcome Here" signs.

Minutes into the first of several videos, the men duck into an alley to "initiate" a member. Five guys punch him as he smiles and shouts out the name of five breakfast cereals.

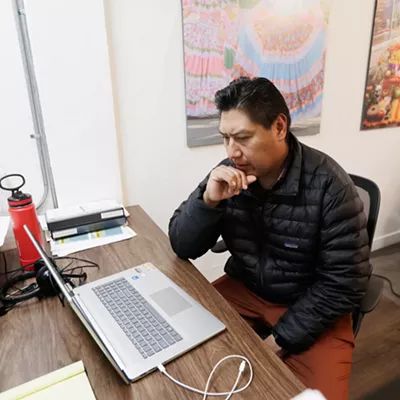

It's absurd, and it's part of the "joke" element of the Proud Boys, says William Hulings, vice president of the Eastern Washington/Northern Idaho chapter that was started in August. Hulings is the one who filmed and posted the Nov. 10 video, and he sees Proud Boys as a drinking fraternity.

But when it's suggested others might not think the group is funny anymore — it's been labelled a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center and linked with violent fights across the country — Hulings concedes that things have changed since its founding in 2016.

"Our country changed, look at our new president," says Hulings, 42, sitting in a Spokane Valley coffee shop. "He's the No. 1 fascist to most people, to most liberals. People hate him, and just like anybody that supports him, we're basically the same."

While the Proud Boys organization has repeatedly tried to distance itself from white nationalism and white supremacy, denouncing neo-Nazis and anti-LGBT sentiments and barring members who hold those beliefs, its members also regularly attend rallies by groups like Joey Gibson's Patriot Prayer group. Gibson's organization also denounces racism, but repeatedly attracts white supremacists to its events. Some Proud Boys have gotten in violent brawls with anti-fascists, or antifa, in and around their gatherings.

"What concerns a lot of people from a community perspective, and apparently also law enforcement, is the fact that there isn't a strong border between them and other more extreme groups," says Kate Bitz, who helps track hate groups in the region as a fellow in the Western States Center's Defending Democracy program.

Hulings, who identifies as a Trump supporter and nationalist (though not a white nationalist), says he's felt targeted. People at progressive rallies here have passed around his picture, claiming he takes inappropriate photos and publishes identifying information on people he disagrees with online — a tactic known as doxing. He says he's personally been doxed after supporting Patriot Prayer in Portland and Seattle, and people have threatened online to "feed this f---er a brick."

Hulings mentions repeatedly that antifa are "kinda our enemy." He despises being called a hate group, and points to the fact he's half-Asian and other members are Mexican as proof they're not racists or Nazis.

But after the "Triggered Spokane" videos were posted, many bar owners began wrestling with the question of whether and how to ban the group from patronizing their establishments.

The conversations caught on camera that night were mostly civil. One woman repeatedly asks "what is a Proud Boy?" if they're really not white supremacists or haters, if everyone online has it wrong. She never gets a solid answer, other than "we're a drinking group."

It's clear, though, that the goal was to get some sort of reaction.

"We don't have antifa fighting in the streets here and that's supposed to be their thing. We don't have that so they're actually out trying to cause trouble," says Tyson Sicilia, owner of the Observatory bar downtown. "They never got the reaction they were looking for."

While the Spokane chapter may seem relatively harmless right now, Sicilia says his biggest fear is what might happen if they do get the reaction they want.

"They look like kind of a joke," he says. "The problem is, the guys that are pissed about them are not a joke. There's some big metal and punk kids that want to stomp them into the ground, and ... I don't want to give them any notoriety, but I also want people to be aware of how to handle them, and not to fight them so we don't have a million more Proud Boys here in Spokane."

How, he wonders, can Spokane's bar scene take seriously the threat of a potential hate group baiting people, while convincing their customers and friends the best thing to do is not to engage?

Last week, Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes, who co-founded VICE Media, announced he was disassociating from the "Western chauvinist" group, which believes the west is best. McInnes said in a video he thought the move might help the court case against Proud Boys involved in a New York City fight last month.

The move came after a Guardian report on a Clark County Sheriff's Office memo that states "the FBI categorizes the Proud Boys as an extremist group with ties to white nationalism." The Proud Boys have tried to discredit the report, and since McInnes' exit, the group has reiterated its rules don't allow racists.

Proud Boys believe adamantly in gun rights, in the "veneration of the housewife," traditional marriage and limited government, according to the group's official publication. They're told not to masturbate more than once a month so they'll be more motivated to interact with women. They're against illegal immigrants. Violence is a central theme: Getting in a fight that's considered justified is an honor.

Hulings reiterates he despises racism, as he was made fun of while growing up in Medical Lake.

"I mean, you hear about these kids getting harassed in school and they come and shoot up the school, that was kinda me growing up, because I look Hispanic," Hulings says, claiming people make wrong assumptions about Proud Boys. "They see somebody with a red hat that says Keep America Great, next thing you know we're some kind of hate group and they can't allow us to go into a business. Seriously, what has this country come to?"

But nationally the group has regularly rubbed elbows with the more extreme alt-right. Locally, Spokane members went into the Checkerboard Bar and told then-bartender Tina Rodriguez that they were going to go to the nearby bar and start a fight with gay men, describing them with a slur, she says.

"That was the last straw for me," says Rodriguez, who quit after she didn't feel the Checkerboard owners took swift enough action to stop the group from coming to the bar. "They make you feel unsure about your feelings about them because you start questioning things. They're multiracial, oh, they're having this perfectly civil conversation with someone, oh, you can be gay and be a Proud Boy. That might be the case, but I don't even think the Proud Boys understand what the Proud Boys stand for honestly."

A few weeks ago, bands stopped booking shows at the Checkerboard after finding out the Proud Boys were meeting there. Co-owner Ashley Maye put out a call to see how she should address concerns. Without naming the group, she said they hadn't caused problems, but she wanted to know what to do.

"At first I'm so confused, why is everyone so offended by this group? Then I did some research, and that was my bad," Maye says. "So I was like, 'OK, so I don't want any of that in the bar.' ... It doesn't matter if you're extreme right, extreme left, religious, that stuff shouldn't be at a bar anyways."

The Proud Boys then claimed they actually meet at the Observatory.

"I said, 'Oh really? They absolutely do not, and they're not welcome,'" says Observatory owner Sicilia.

Soon, someone stole pictures from his Facebook and created a new page in his name, posting Nazi and KKK memes making him look like a white supremacist. He got the account removed and reported to police, but it was a taste of the rapid social media reaction the group is known for.

Within a week, the "Triggered Spokane" videos were uploaded. The fact that they appeared to target specific bars known for being accepting put some people on edge.

Sicilia says the Observatory has high-definition cameras both outside and inside the bar, and since this happened, he's bought an ID scanner so his staff can flag people who they find out are extremists or causing trouble. Hate hasn't been and won't be allowed in his bar.

He and others like Patty Tully, longtime owner of Baby Bar, plan to meet again this week to figure out the best tactics to address the group with a united front.

Over the years, Tully has had to kick drunk people out, and it's usually like dealing with toddlers, she says. They always leave when she tells them, and many come back to apologize later.

But with this group, it's less clear how they're going to react, she says. How do you keep people from all walks of life comfortable in the bar, and keep a situation from escalating if you want to ask someone to leave?

"We've always said everyone is welcome, but the minute you make anyone uncomfortable you have to leave," Tully says. "I do not want them sitting up front at Neato where everyone can see them, making people feel uncomfortable. That's not why I have a bar, you know?"

Guidelines for how to ask them to leave could help, she says, as could trying to catch things on camera if there's an issue. That way, if the group is also filming, they can't edit footage and make it look like someone was getting kicked out for being a veteran or for their race.

But the main key to all this is to diffuse the situation, she says.

"That's the thing that's scary about that, when people are drinking, that's opposite of what people think about doing, especially at all these bars, people feel like it's their home bar," she says. "It's hard enough to run a bar where you're serving people a legal drug, and now you have to worry about this? It's crazy." ♦