Taliban forces came knocking at a home in the Helmand Province of Afghanistan on July 31, 2021, looking for an engineer by the name of Faridoon Sharif. They want to use Faridoon's house as the command center for an assault against the nearby police precinct, but it's Faridoon's mother who answers the door.

Through a torrent of tears, she insists repeatedly to the Taliban that her son isn't there.

It wasn't true.

When Faridoon built his house, he'd included a secret room where he or other family members could hide. And that's where he and his two brothers are hiding as their mother pleads with the Taliban to leave.

And it works. Even in the Taliban, Faridoon says, there "was a good person." He agreed to use a neighboring house as their headquarters instead and leave Faridoon's family alone.

"We were very afraid, sir," he tells the Inlander now. "We were in a bad condition."

Eleven years earlier, he'd been working as an office manager for a civilian counternarcotics operation aligned with the United States. His work with the U.S. had put a target on his back, but in exchange, he was eligible for a "Special Immigrant Visa" — a path out of the country.

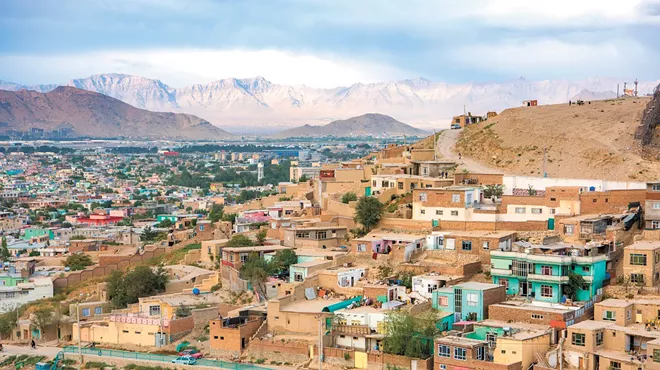

However, as Afghanistan's military and government swiftly collapsed, his paperwork still hadn't been approved. He and his family had rushed to Kabul, the Afghan capital, to escape. They'd been delayed — the bus driver, he recalls, fell asleep, and they'd had a minor accident on a bridge. By the time the last American cargo plane lifted off from the Hamid Karzai International Airport on July 30, 2021, Faridoon's family wasn't on it.

They'd been left behind. The Inlander wrote about his story at length last year ("Fleeing," Sept. 9, 2021) — relying on WhatsApp messages and other documents to tell his story — and we changed his name to protect him, calling him "Sayed."

Today, he's given us permission to use his full name. That's because Faridoon and his immediate family are finally safe in the United States. But that was only possible due to a flurry of lobbying that included efforts by Spokane County Treasurer Michael Baumgartner and his wife, Eleanor — who both worked with Faridoon in Afghanistan in 2009 — and a former Trump State Department spokeswoman.

"I never forget, sir," Faridoon says of the people who helped him get out. "I never forget."

To survive, Faridoon grew a beard. Not only were beards a crucial part of the Taliban's ultraconservative religious doctrine, but he hoped it would obscure his identity.

"I have a big beard, and I thought no one can recognize me," he wrote in a What'sApp message to Eleanor Baumgartner last September. "But I was wrong. Everyone knows me."

Phone calls from unknown numbers kept coming in, telling him they knew what he had done during the previous government and to count his days if he didn't give them money.

As early as September 2021, the Baumgartners hoped they could ferret out another flight from Afghanistan to allow Faridoon's family escape. But Faridoon couldn't just stay in Kabul and wait for the possibility. He literally couldn't afford it.

"I didn't have any money," Faridoon says. "The bank system was gone. Fully gone."

Within just a few months of Taliban rule, The New York Times reported, the entire Afghan economy was collapsing. Half of the country was facing starvation. Faridoon's wife got seriously sick and had to go to the hospital.

Faridoon borrowed money from his uncle, a local doctor who had enough cash to help him get by. And he went back to work, working as a liaison for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, an agency that helped distribute aid packages across Afghanistan. That gave him a salary. But it also put him in contact with Taliban leadership.

In October, he says, a Taliban leader, a minister of rehabilitation, called him into his office. Terrified, Faridoon asked his friend to accompany him.

Faridoon says the Taliban leader's behavior was atrocious, denying him all of the important customary Afghan signs of respect — effectively treating him like a "cow." He wanted Faridoon to help him distribute a thousand U.N. aid packages to families, handpicked by the minister, in the Helmand Province's impoverished Sangin District.

But Faridoon pushed back, telling him that that wasn't how it worked — they had to first survey the population to identify the neediest families to give the aid kits to. In response, Faridoon says, the Taliban minister pelted him with a barrage of insults, including accusing him of being American.

"'Don't speak, son of Joe Biden,'" Faridoon recalls the Taliban leader sneering.

On the one hand, it showed that the Taliban still wanted what aid they could get from the international community. On the other hand, it demonstrated the contempt — and danger — that Faridoon was risking.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, a crew of people were fighting for Faridoon's case. It wasn't just the Baumgartners. U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers' office was pushing, too. So was Heather Nauert, a former Fox News journalist who'd served as the Trump administration's State Department spokeswoman from 2017 to 2019.

At one time, Nauert had been slammed for offensive statements she'd made about immigrants and Muslims. But for the past year, she's been one of the many working behind the scenes to help Afghans who'd worked alongside the Americans reach the United States, including Muslims like Faridoon.

"I was personally horrified by the thought that we would leave behind people who had served alongside us," Nauert tells the Inlander. "We said, 'You work with us, and we'll bring you to safety.'"

Some of them, she says, have done more for America than many Americans have.

In trying to help their former Afghan coworkers get out, meanwhile, the Baumgartners had reached out to Tiffany Smiley, the candidate running against Sen. Patty Murray, hoping she'd have connections that could help Faridoon. Smiley happened to know Nauert. Smiley gave Nauert a list of people — including Faridoon — she was trying to help get out of Afghanistan.

"I started raising his case with people I knew at the State Department," Nauert says. "I'm saying, 'Look, this guy has to get out.'"

But there was a whole forest of red tape that special immigrant visa applicants faced.

"There were forms all written in English that the U.S. government expected these Afghans to fill out," Nauert says. "They had unstable internet connections. At this point, they're starting to hide from the Taliban, in safe houses."

If it wasn't for a lucky break, Nauert says, Faridoon would likely still be in Afghanistan: She learned that Faridoon's father was a U.S. citizen — and his mother was a green card holder. And suddenly, Faridoon shoots to the top of the priority list.

But there are still kinks to work out. Nauert and Eleanor Baumgartner help Faridoon work his way through the reams of paperwork. By now, it's December, and Faridoon wishes both of them a Merry Christmas.

He and his family return to Kabul, staying in a hotel for months as they wait for the chance to board a plane. But the flights are repeatedly canceled. The water and the food are horrible, and he and his mother get seriously sick. And by February, the Taliban announces a travel ban, forbidding anyone who has worked with NATO or the Americans from leaving the country.

By then Faridoon's passport is set to expire — and if he doesn't get out soon, it could mean weeks, even months, more of delay.

"I am getting crazy, Eleanor," he writes in a message. "They stole my dream."

On March 10, Faridoon's son takes his phone and sticks it over a hotel lobby balcony, recording members of the Taliban crowded around the reception desk.

"Hello Eleanor, I have to inform you that the Taliban are constantly coming here at night to search to come and get information," he says over WhatsApp. They're asking about Faridoon. They want to see documents.

Time is running out.

On March 30, a plane finally lifts off from Afghanistan. Faridoon is on it. The process is so opaque that Eleanor doesn't know exactly what happened to allow him to leave.

When his plane finally clears the runway, Faridoon watches his homeland disappear into the distance.

"It was very difficult," Faridoon says. "I was leaving my homeland. I cried a lot."

But the destination isn't the United States. Not yet. He lands in Qatar. At a camp established at As Sayliyah Army Base he finds a bathroom and shaves his beard.

The beard may have been on his face, but he says, "This beard was not mine." It was the Taliban's. Shaving it off means he can return to being himself.

For three more months, he jumps additional hurdles in his path to America. First, his baby contracts COVID, putting the whole immigration process on hold. Then, one part of the U.S. State Department needs documents from another part, but can't get them.

"Welcome to Western bureaucracy," Eleanor Baumgartner writes to Faridoon in April. "It is making me crazy."

But Qatar is much safer. The food, Faridoon says, is excellent. And finally, the last hurdle is cleared. He arrives in the United States on June 16, nearly a full year after Taliban forces arrived at his home.

Today, Faridoon is living in San Antonio. He invites the Inlander to come to his house if we're ever in the area. He would be proud to serve us dinner. For everyone involved, Faridoon's escape is undercut by just how many similar Afghans are still trapped there.

"Those lucky Afghans who are able to get out are few and far between," Nauert says. "There are so many more left behind — the stories we don't hear about."

That includes other members of Faridoon's family. His mother is still in Afghanistan. His little brother — who recently got married and had two kids — is still there, too.

The pipeline is getting narrower, Nauert says. Despite the need, there are fewer State Department resources to help remaining Afghan allies leave the country. The war in Ukraine has diverted public attention.

"So U.S. sentiment shifted gears altogether and really started focusing in on helping those [Ukrainian] refugees," Nauert says.

But make no mistake, Faridoon says he's incredibly grateful.

"This is my second country," Faridoon says. "I can start my life here and serve America. This is my second homeland."

The Taliban had accused Faridoon of being an American. In a way, they weren't entirely wrong. They were just a few months early. ♦