Angel Dwyer's family came to North Idaho for the beautiful log cabin home they were able to buy in the middle of nowhere, not too far from the pristine waters of Priest Lake. They came because Idaho is a place known for respecting personal freedoms. They came because they knew people wouldn't ask questions.

Questions like: How old is Angel? And how old is her husband?

They wouldn't ask about the wedding ceremony Angel's mother conducted in their living room or how she'd directed her newly 13-year-old daughter, dressed in a mail-order wedding gown, to read handwritten vows to her 16-year-old tuxedoed boyfriend.

They wouldn't ask how the boy had come to live with Angel's family in California, or why Angel's mom and stepfather would encourage such a young girl to marry the second boy she'd ever had a crush on.

This story isn't from the distant past: That young girl is now a busy 27-year-old mother of five living in Sandpoint. Sitting in a bustling coffee shop there one morning in March, the short woman with long brown hair nervously smiles as she lays out how that marriage impacted her life.

"All of my childhood, my teenage years and everything I could've done as a young adult has been stolen from me, by people who made decisions and had the freedom to make those decisions for me," Angel says, keeping her composure despite tears rolling down her cheeks.

Looking back on her wedding in California, she doesn't happily recount the ceremony or proudly recall that, at 13, part of her felt like a little princess who was about to get her "happily ever after." No, that fantasy was ultimately tainted by years of living with an abusive husband, by memories of a mother who never told her she deserved better and by traumatic experiences that took her years to finally escape.

Instead, when Angel quietly describes her wedding day, the thing she focuses on most is that each and every adult in that living room could have said something — should have said something to stop it.

"My neighbors, they knew something was wrong because my boyfriend came to live with me, and then they stopped letting their kids hang out with us," says Angel, whose last name is now McGehee. "My stepdad, my mother, his mother, my neighbor, my aunt — all of these people could've said, 'This is wrong. Why is this happening?' but nobody did."

The U.S. State Department calls child marriage a "human rights abuse" — and wants to ban the practice in other countries — but in America, all but two states allow kids under 18 to marry under certain conditions, generally with approval from parents and, in some cases, a judge. Over the past 20 years, more than 200,000 children like Angel have been married in America, the vast majority of them to adults who might otherwise face charges of statutory rape.

Idaho, in particular, has the highest rate of child marriage per capita in the country, according to one study. The Gem State ranked higher than Kentucky, Arkansas and Wyoming in a comparison of 38 states where data was available.

The consequences can be huge: Studies show American minors who marry young are 31 percent more likely to be impoverished, 50 percent more likely to drop out of high school, and an estimated three-quarters of marriages involving a child end in divorce. Most underage spouses are young girls, and research shows they are more susceptible to frequent pregnancies and violence.

States are beginning to rethink their stance on child marriage, with nearly a dozen legislatures considering laws this year to end exceptions allowing marriage under age 18. Washington state lawmakers introduced a bill in February to eliminate those exceptions, but it never received a hearing and died.

Meanwhile, Idaho lawmakers considered a compromise bill last month that would have aligned the state's marriage laws — which have allowed girls as young as 13 to marry in recent decades — with its statutory rape laws, leaving in place exceptions only for those who are 16 or 17.

But Republican lawmakers killed the bill, arguing that parents and families should have the freedom to do what they feel is best. For her part, Angel wishes she had known about the bill and that she had a chance to explain how some freedoms come at a cost.

"My mother's freedom to do whatever she wanted with me here was the catalyst to my imprisonment to what she wanted to do with me," Angel says. "The freedom of parents to do whatever they want with their kids means their kids have no freedom if their parents don't want them to, and that was me. I had no freedom. Government is supposed to protect the people, individuals who have no power. I had no power and nobody protected me."

IDAHO RULES

Idaho Rep. Melissa Wintrow, a Democrat representing the north Boise area, first considered changing the state's marriage rules while serving on a human trafficking subcommittee. One of the things that came up was the possibility that people travel to other states to marry because the rules are more lax.

"So I start asking more questions and realize we don't even have a floor for the minimum age of marriage," Wintrow says. "To think that somebody 30 could marry somebody 13 didn't seem appropriate, especially such as that our consent laws say that you can't consent. ... We're defining statutory rape, but then we have a loophole for some people to get around it."

In Idaho, those who marry under the age of 18 are almost always girls, and in recent years they've legally married men in their 20s, 30s, 40s or even older.

Idaho allowed a 20-year-old man to marry a 13-year-old girl in 2001, which would have been considered statutory rape outside of that institution getting approved by a parent and a judge. It also allowed a 46-year-old man to marry a 16-year-old girl in 2006, and in 2010, a 65-year-old man married a 17-year-old girl, according to state health data.

To prevent Idaho from becoming complicit in child abuse, Wintrow suggested aligning the state's marriage law with its statutory rape laws. That means no one under the age of 16 could marry, and those who are 16 or 17 would need to get parental permission as well as judicial permission, and they could not marry anyone more than three years older than them.

Currently in Idaho, those who are 16 and 17 just need parental permission, and those under 16 need a judge to agree that a medical professional has signed off on the child being mature enough for marriage and that the union would be in the "best interest of society." (In Washington state, those who are 17 can get married with parental consent, and under that age, court permission is also needed.)

Wintrow also proposed that the judge would need to find the marriage is in the best interest of that child.

"We've come a long way, but girls are still kind of fed different cultural messages about being rescued and the importance of a man in your life," Wintrow says. "I remember what it was like to be 14, 15, you've seen all those Disney movies and it's before you've had the chance to experience the world. You're easily coerced or persuaded. We need to safeguard them."

In committee, Wintrow invites Judge Barry Wood, deputy administrative director of the Idaho Supreme Court, to answer questions about the judicial approval process. Lawmakers want to know how the courts sign off on these cases where children are under 16, and he quickly explains that they're rare, but there is a fairly simple process.

"A petition needs to be filed, there has to be consent, and the court needs to employ the services of a physician who has to opine that the person under 16 is capable physically and mentally of performing the contract of marriage," Wood tells a House committee on Feb. 21.

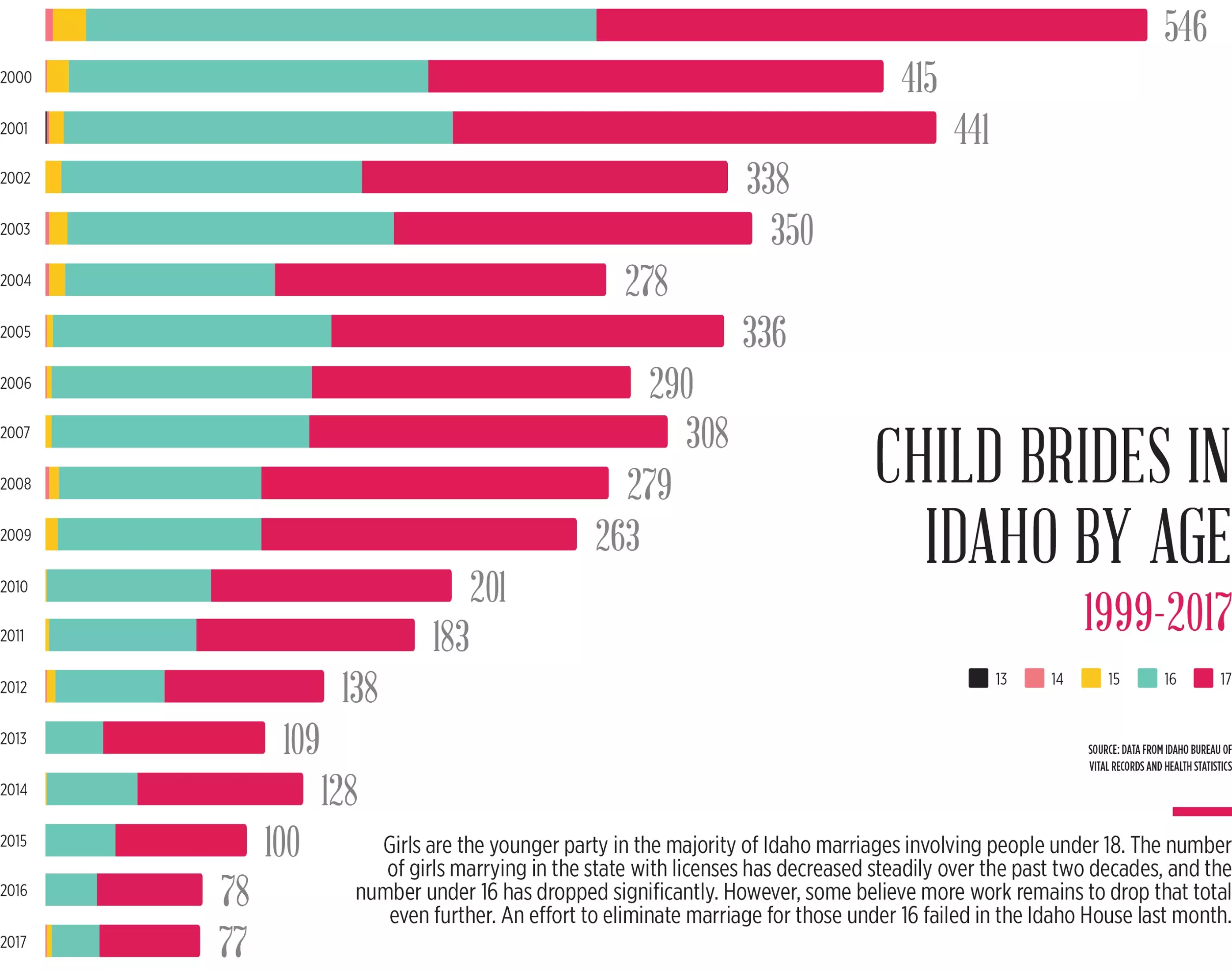

Idaho state health data shows that the number of teens getting married has steadily decreased over the last 20 years. More than 540 girls under 18 and about 100 boys under 18 were married in 1999, which dropped to about 75 girls and 15 boys in 2017.

In total, 4,858 girls under 18 were married in the state between 1999 and 2017, the most recent year for which data was available. Of those, 105 were 15, 14 or 13 at the time of marriage, making up about 2 percent of the child brides who got state licenses.

One of the main concerns for the Idaho Coalition Against Sexual and Domestic Violence, which worked on the bill with Wintrow, is whether any of those teens who are under 18 could adequately protect themselves or utilize the courts if anything were to go wrong with their marriage.

"If you look at young women ages 16 to 24, they experience the highest rates of intimate partner violence," says Annie Hightower, the coalition's director of law and policy. "So I guess our concern with that then is, when you have these young women who are married, often to men who are much older than them, they don't have any means of protecting themselves."

While some Idaho case law exists establishing that minors become emancipated when they're married, actually being able to access domestic violence services or get to court to represent yourself could prove extra difficult for teenagers, especially if they can't drive, Hightower says.

"They may not have finished high school, they may not get assistance to file for divorce in court, or in some rural communities even be able to get there," Hightower says.

Before Wintrow's House Bill 98 goes to the floor for a vote, Hightower speaks with some waffling legislators. She's not sure if there's enough support for the bill in Idaho, where there's a premium placed on religious and parental freedoms.

"I think there is a really strong feeling here in some communities if you end up pregnant you should be married, regardless of the age," Hightower says. "And I'm sure there are also those people that have been together with their high school sweetheart since they were 14 and think, 'This worked for me.'"

Indeed, when the measure reaches the House floor on Feb. 28, Republicans who speak in opposition to the bill cite teen pregnancy and familial freedom as primary reasons for voting against the changes.

Rep. Christy Zito, a Republican representing southwest Idaho, questions the statistics on high divorce rates and points to how many Idaho high school students are sexually active. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found about a quarter of Idaho's high school students reported they were sexually active in a 2017 study.)

"If we pass this law, it will then become easier in the state of Idaho to obtain an abortion at 15-and-a-half years old than it will to decide to form a family," Zito says.

On the Democratic side, Colin Nash, filling in for Rep. John McCrostie (D-Garden City), argues that Idaho is enabling forced marriages like that of resident Shirley Perez, who shared her story with the Post Register in Idaho Falls last summer. She was married at 13 to her 39-year-old rapist in the 1960s, had five children and was left penniless after finally escaping the abusive relationship, he recounts.

"When it's legal for a 30-year-old to marry a 15-year-old, that is not marriage, because they are not equal partners. That is institutionalized child abuse. That is arranged statutory rape," Nash tells fellow lawmakers during the debate. "I think debates over the last decade have shown this body to believe it has a duty to define and protect the sacred institution of marriage. But marriage in Idaho cannot be a sacred institution so long as it institutionalizes child abuse."

Shortly after, the House rejected the bill with 28 votes for and 39 votes against, with three excused. Republican Reps. Heather Scott and Sage Dixon, whose district covers Sandpoint, were among the no votes, and only one North Idaho lawmaker, Rep. Paul Amador (R-Coeur d'Alene), supported the bill.

"I was at a loss, honestly, because I do think I compromised," Wintrow tells the Inlander after the vote. "We set ages for a reason — that's why people are banging their fists I didn't put it at 18, because that's more in line with the other age appropriate lines in the sand we've drawn for engaging in contracts on your own. But again, I was trying to compromise, and even then, the compromise wasn't enough."

STOLEN YOUTH

Growing up, Angel says her mother had always been skeptical of government and anyone who might tell her how to raise her children. She'd homeschooled them, which is a generous way of saying she never put them in school, but taught them the basics of how to read and write, Angel explains. They never went to the doctor or the dentist. Even the public library was considered too government-connected, so they weren't allowed there either. Angel's only connection to the outside world was through the internet and the few neighbors next door. Soon after the wedding, Angel's mother worried even they might be a threat.

"I only had her, I didn't have any coaches or any mentors or anybody else speaking into my life," says Angel, who has been estranged from her mother for several years now. "We were very isolated, very secluded, and that's why she moved us into North Idaho, because nobody around here in the boonies of North Idaho asks questions about those sort of things."

Just after her living-room wedding, which was her mother's idea, Angel says her family encouraged her to go lose her virginity in the other room to her new husband. By 14 she was pregnant, and at 15 she had her first son.

Now that her oldest son is 12, Angel says she realizes just how strange it was that when she told her mother she had a crush on a boy she'd met in an online gaming forum, her mother's response was to fly the family out to meet him in New York. She ended up marrying that boy's best friend, whom she met on the trip.

"I still wonder, 'What the heck? Why would you do that, when your daughter's 11 and interested in some boy over the internet?'" Angel says. "Think of that. I have a 12-year-old son. I look at him and I think there is absolutely no way I would ever think, 'Let's get you married to the first girl that you're interested in!'"

So it made her mad to see that a majority of Idaho representatives found no problem with children as young as she was getting married.

"It's like they're saying that my experience was OK. Like it validates it somehow to them," Angel says. "If a 13-year-old girl cannot get a tattoo, cannot smoke, cannot, you know, do any of those, why should she be getting married and having babies? Those are choices that affect the rest of your life, and we prevent children from doing other things that we know are harmful for them."

"I remember what it was like to be 14, 15, you've seen all those Disney movies and it's before you've had the chance to experience the world. You're easily coerced or persuaded. We need to safeguard them."

Because her marriage was actually performed without a license, the Idaho legislation didn't directly affect her, Angel says, adding: "But it did indirectly affect me because that's why my parents moved here, because of the fact [that] legislation like this is in place."

Sure, she notes, in some cases, young marriages could turn out fine. But hers was extremely limiting.

"You can't do certain things without permission, so he becomes your legal guardian, your legal authority," Angel says. "So if he's abusive? It ends up where you are a prisoner."

She didn't have a driver's license or a job. She became completely dependent on a husband she says strangled and berated her on a regular basis. When he choked her again while she was pregnant with their third child, she reported him to the police with the help of Priest River Ministries Advocates for Women, and he wound up serving time behind bars.

For her, maybe the hardest thing is feeling like she lost out on the opportunity to enjoy her youth. After separating from her first husband, she spent two years single and then dated and married a man she says has been a great partner to her. They had two children together, so she's now got five kids between the ages of 2 and 12 to take care of. She never got the chance to go to school, or to learn who she was as a person before having to raise other people and teach them how to be independent.

"Look at all the good years we could've had when I was a teenager not knowing who I was and not knowing what I wanted to do with my life," Angel says. "I feel a lot of guilt for saying there's part of me that wishes I didn't have my kids so young because there's so much I want to do in life. It's not about them, right? It's not about not wanting them. Just maybe it would've been nice to have them a little later. But now that I have them, all my life is devoted basically to being a mom."

FIGHTING THE FIGHT

In recent years, more attention has been drawn to the issue of child marriage both domestically and abroad.

The Vatican announced in February that Pope Francis would raise the allowable age of marriage for girls in the Catholic Church from 14 to 16, to match the minimum age for boys.

In 2018, Delaware and New Jersey became the first two states to restrict the age to 18 or older, with no exceptions, and several other states are considering similar rules.

A major proponent of that type of legislation is Fraidy Reiss, executive director of Unchained At Last, an organization she founded in 2011 to help girls and women avoid or get out of forced marriages after getting out of her own forced marriage.

"This is the reason I became so passionate about ending child marriage: More and more girls under the age of 18 started reaching out to Unchained to ask for help either avoiding a pending forced marriage or getting out of one that already happened," Reiss says. "I discovered there was almost nothing we at Unchained could do for these girls."

Girls under 18 often can't stay at domestic violence shelters due to liabilities based on their age or state laws about runaways, Reiss says.

"Also in some states, an advocate who helps a child leave before 18 can be charged legally," Reiss says. "That happened: One of our volunteers was charged criminally for helping a girl."

It's hard to find an attorney to represent someone under 18, because contracts they sign could legally be found to be void, Reiss says. In some states, those under 18 can't represent themselves in court for a divorce without a parent or guardian petitioning for them.

"If this girl was forced to marry, it was probably her parents who did that. Now she has to go to her parents and say, 'This guy is not good. Please help me divorce him,'" Reiss says. "That's why I say marriage before 18 is so dangerous. This is not about maturity, we all know very mature 17-year-olds and, by the way, very immature 40-year-olds. ... We're talking about entering into a really serious contract, typically the only contract states allow children to enter before they have the tools they need. This puts the lock in wedlock."

Reiss knows from experience that parental permission often looks more like parental coercion, even for those who don't legally need permission anymore. She was 19 when she was forced into an arranged marriage that became abusive. After 12 years, she was able to escape with her two children, but her ultra-Orthodox Jewish family shunned her. She had to create a new life on her own, which is why she wanted to start Unchained, to help others escape situations they didn't need to be in.

In the several years Unchained has been around, they've helped more than 500 people, mostly women and girls. Reiss says she had expected to find that religion would play a common role, but in fact, she says child marriage and forced marriage crosses every spectrum.

"This is happening in every major religion, minor religion, and also in secular communities. In every socioeconomic level, with immigrant families, on every inhabited continent, as well as with families that have been in the United States for many generations," Reiss says. "That was surprising to me."

Noteworthy for Reiss is that the State Department has called marriage under 18 a human rights abuse that "produces devastating repercussions for a girl's life, effectively ending her childhood."

The idea that states like Idaho enable a judge to sign off on those young marriages and make exceptions seems especially perverse, she says.

"That a judge could find that a human rights abuse is in a child's best interest, that's offensive," Reiss says. "When a child is being forced to marry by their parents, you'd think judicial review would eliminate that, but unfortunately what we have seen is when a child is forced to marry, again, usually the parents are forcing them to."

To change the practices of child and forced marriage will take both legislation and a cultural shift, Reiss says.

"We want to get people thinking again about the value of the girls and the role of marriage, and the value of women in general beyond their ability to bear children," she says. "Legislation has a really powerful impact and I think a really powerful ability to make people stop and think, 'Well, why isn't child marriage illegal here?'"

MOVING ON

Years after separating from her first husband and spending time in a domestic violence support group, Angel is just now starting to feel like she's finding some balance in her life.

She volunteers once a week with Priest River Ministries, which she credits with saving her life and enabling her to get out of an abusive situation. They helped partner her with an attorney who helped her prove she was born in New Jersey and get a birth certificate, which enabled her to get a driver's license, which enabled her to find work.

"I just got a part-time job, so my life at this point is really now just blossoming, because I have a super supportive husband," Angel says.

She's thinking about going to school, though she's not sure yet what she wants to study. Because she and her siblings basically fended for themselves, both for sustenance and for education, Angel says she has an incredible hunger for knowledge.

"I realize that education is the most empowering thing," Angel says. "You see it throughout history, when that is removed from people — when they are not allowed to learn, to read, to have access to education, to have access to opposing viewpoints, when they are brainwashed — they are able to be controlled. To me, education is the most empowering, the most freeing thing someone could have."

Though she grew up in a secular household, Angel joined a Bible study to make friends when her family moved to Idaho, and that helped create her first connection to the domestic violence agency. She's now considering going to divinity school.

"A huge part of my life is God and loving people like Jesus did," Angel says. "Part of that to me is standing up for those who are oppressed and setting the captives free."

She homeschools her oldest children, but says they'll likely enroll in school, and her youngest will likely start school from the get-go. In the meantime, she makes sure they have access to as many educational tools as they can, and enrolls them in plenty of extracurricular activities.

"Unfortunately I think I overbusy it sometimes ... I recognize that's because I never want them to feel like I did, where I had no opportunities. I don't want them to ever say to me, 'Mom, you didn't let us do what we wanted to do,'" Angel says. "'Cause I want to say that to my mom. I want to be able to say to her, 'Mommy, you didn't let me do anything I wanted to do in life, and that sucks because that's not what parents are supposed to do. Parents are supposed to protect their kids.'"

It's still extremely difficult for her to process what she's been through. Angel says she still suffers from PTSD, which hasn't always made things easy in her new relationship, "but he's just an amazing man who loves me in spite of all the mess."

Some of the healing process has meant letting herself try some of the activities she always wanted to do. She started doing improv last year because she always had an interest in acting and says it's been "the most freeing thing ever."

"Finding little things to get out and nurture my spirit and who I am has been good," she says. "The more I go over it, I guess the more it becomes a little easier, but I don't know if it'll ever [feel right]. Because all of those years are gone and I can't get them back, I don't know if I'll ever be OK with that. And that's why I don't want that for other people."

Her hope is that by sharing her story, those in similar situations know that they have value, what is happening is not their fault, and there are ways out.

"I know a lot of other women are out there experiencing the same thing I did," Angel says. "I want them to know that there's hope, and that there is a life after." ♦

GREEN CARD CHILD BRIDES

While states start to consider eliminating child marriage, advocates who work to end forced marriage globally say that federal immigration law may also be enabling the practice, with some girls being married off for citizenship purposes.

Currently, immigration law allows citizens to request a visa for a spouse if they're a minor, so long as the marriage was legal in the country of origin. American minors can also request visas for adult spouses from other countries.

From 2007 to 2017, the United States received nearly 8,700 visa petitions where either a spouse or fiancé was a minor, according to a January 2019 congressional report for the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. The majority of those requests were likely approved, and in 95 percent of cases, girls were the younger spouse, the report states.

The issue intersects with state policy because U.S. immigration law is also supposed to look at whether the marriage would be legal in the state they plan to live in, and many states still allow exceptions to be made for those under 18.

One American woman shared with Congress how she was forced to marry her cousin at age 13 while on a trip to Pakistan so he could later attempt to get citizenship.

After those concerns about the system were flagged, the Trump administration announced in February that U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services will scrutinize applications involving minors more closely, the Associated Press reports.

SCANDALIZED

Over the years, some famous cases involving young brides scandalized the U.S. and also helped spark rule changes.

In 1926, people were offended to learn about 51-year-old millionaire Edward "Daddy" Browning's marriage to 15-year-old Frances "Peaches" Heenan. Shortly before the two had met, "Daddy" had famously conducted a public contest to find a daughter about that same age to adopt as a sibling for his other child.

A decade later, 22-year-old Charlie Johns posed for photos with his new 9-year-old wife, Eunice Winstead, in Tennessee for the February 1937 issue of Life magazine. The girl's mother said she had no problem with the marriage and indicated that, at least at first, the two weren't living together. That scandal prompted the Tennessee Legislature to raise the minimum age for marriage to 14 within weeks.

BY THE NUMBERS

The United Nations estimates nearly 33,000 girls under 18 get married around the globe every single day. That's about 12 million a year. Of the more than 200,000 children who got married in the U.S. between 2000 and 2015, 87 percent were girls, and 86 percent were marrying adults, according to PBS Frontline research that built on numbers compiled by Unchained At Last and Tahirih Justice Center, organizations that work to end forced marriage and child marriage.

Samantha Wohlfeil covers the environment, rural communities and cultural issues for the Inlander. Since joining the paper in 2017, she's reported how the weeks after getting out of prison can be deadly, how some terminally ill Eastern Washington patients have struggled to access lethal medication, and other sensitive investigations. She can be reached at samanthaw@inlander.com or 325-0634 ext. 234.