It was March 27, 2022 — just after the end of the Idaho legislative session — when Blanchard, Idaho resident Andrew Scott gained federal copyright protection for the photo of his wife.

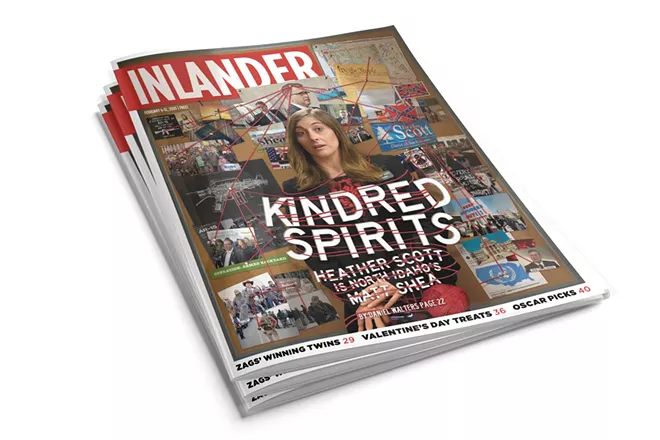

By then — nearly seven years after it had been taken at the 2015 Timber Days parade, and two years after the Inlander republished the photo in a cover story — the photo had already gotten a bit of fame.

It wasn't that the photo itself was particularly artistic. It was the incendiary subject matter. It shows his wife, Idaho state Rep. Heather Scott, standing on a parade float with her campaign sign, smiling and holding that symbol of slavery and secession, the Confederate battle flag.

This was shortly after nine churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, were gunned down by a white supremacist with a Confederate flag license plate. While South Carolina's then-governor, current Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley, had removed the flag from public display, Scott was holding it high.

She'd not only posed for the photo, she'd put it on her legislative Facebook page. And soon, the photo was everywhere.

The Spokesman-Review wrote several stories on the ensuing controversy, using the photo each time. It's appeared in the Sandpoint Reader, on KUOW, in the Inlander, and on public radio websites. To this day, she has the photo posted, uncredited, on her campaign website where she writes, "I posed with a Confederate flag on a parade float to show that our First Amendment right is one of the most important rights we have."

In documents submitted to the U.S. Copyright Office in 2021, Andrew Scott titled the picture "In Defense of the First Amendment."

Then, this February, the day after Heather Scott attended a Kootenai County Lincoln Day Dinner with U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, her husband sent a letter to the Inlander and at least one other journalist with a legal threat over our use of the photo, saying we'd be liable for up to $150,000 in damages.

"Weaponizing copyright" isn't new, says Cathay Smith, a University of Montana professor who wrote a 2021 paper for the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology on attempts by powerful figures — everyone from Harvey Weinstein to the Church of Scientology — to silence criticism and hamper investigative journalism by using copyright claims.

But it sure feels to Smith like it's becoming a more common strategy.

"If you can imagine the number of people who don't fight back, or don't get that public platform to air out this problem, it could be happening a lot more than we realize," Smith says in an interview.

BALANCING FAIR

The Inlander wasn't the only place to get a legal notice from Scott: Heath Druzin, a freelance audio journalist who produced the "Extremely American" podcast covering the far right, got a similar threat in the mail.

"My first instinct was that this sounds like an intimidation tactic," Druzin says. "This is somebody who already has a hostile view and hostile relationship with the press. This seemed like a tactic to silence me."

He doesn't recall even publishing the photo in a news story. He just posted it on Twitter in January after Heather Scott sent out a tweet making fun of another reporter.

"I can only assume that that is what got Heather Scott's attention," Druzin says.

To him, the threat seemed completely ridiculous.

"I'm a freelancer. I'm my own boss," Druzin says. "If you don't have a big company behind you — like a McClatchy — some people might think it's easier to bully somebody."

Druzin reached out to an attorney, who confirmed what multiple legal, academic and media experts told the Inlander: Journalists using the incendiary photo that Scott had posted on her own Facebook page and campaign site would qualify for the "fair use" exception.

"Being the advocate of the First Amendment she claims to be, we are certain Ms. Scott understands and appreciates the implications of denying fair use to any newspaper" reporting on the government she's part of, read, in part, the Inlander's response to Andrew Scott.

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to establish copyright and patent laws to "promote the progress of science and useful arts." But soon, American judges began to identify reasonable exceptions to the laws. By 1976, the principle was officially embedded into U.S. copyright law: Journalists and others can use excerpts of copyrighted material for "criticism, comment" and "news reporting."

"The photo itself is newsworthy," says Al Tompkins, an expert on journalism with the Poynter Institute. "In my opinion, you have no journalistic duty to remove an image that's true, that's contextual and that's important."

But even for journalists, fair use isn't automatic. Judges have to weigh a number of factors, including how much of the work is used, whether the use is "transformational" — altering the image or offering additional context or commentary — and whether sharing it hurts the creator's chance of making money off the work.

"You know how newspapers will take hot pictures of the year and put them on T-shirts and coffee cups?" says Michele Earl-Hubbard, a Washington state media attorney.

Don't do that with a copyrighted photo, she says.

The same principle also protects the rights of conservative activists like the Idaho Freedom Foundation to republish photos of pages from school library books it finds offensive on their website.

In fact, Dustin Hurst, former vice president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, says they were once hit with a copyright threat from a media outlet over a copyright claim about a photo they'd used of a politician. Their attorney, Hurst recalls, replied "look, stick it" and cited fair use.

As for Heather Scott? She republished the Inlander cover featuring her and the Confederate flag, calling it "fake news" and "great firestarter" before asking her followers to save her a copy. Fair use protects her use of this image just as it protects our use of her public photo.

LAWSUITS A-PLENTY

Still, newspapers are understandably skittish about copyright these days. After hearing about Scott's copyright threats to two reporters, the Idaho Press Club's First Amendment Committee met about the issue.

"We're all being much more careful now," says Betsy Russell, another reporter who used Scott's Confederate flag photo in a news story in the Idaho Press. "Copyright law is really complex."

In the past decade, she notes, there's been a slew of "copyright trolling" — attorneys who send out massive numbers of copyright threats in hopes of getting payouts and settlements. Even politician-provided candidate headshots have landed newspapers in hot water with copyright claims.

Shortly before she retired this year, Russell says she learned of a new policy from the publishing group that owns the paper.

"We would no longer be accepting any submitted photos from anyone," Russell says. "Unless they went on our website and filled out a form that included certifying that they own the rights to the photo and that they grant us permission to run it."

But in many of the cases that Smith studies, making money isn't the goal. Removing content is.

In some cases, the plaintiffs are sympathetic. Before revenge porn laws, she says, "copyright was a faster framework for someone" to get a website to remove a person's explicit images than existing privacy. Other times, they're absurd. Smith says someone sued "their ex-partner, claiming copyright to their text messages."

But then there are cases where someone is simply looking to punish someone they don't like. In 2007, right-wing talk show host Michael Savage sued the Council on American-Islamic Relations for republishing an anti-Islamic rant from his talk show. While CAIR won that case, Smith says, they were still stuck with the significant legal fees, and Savage seemed even more emboldened to use that tactic in the future.

Of course, if you really piss off a powerful person, copyright isn't the only weapon they have in their arsenal.

"The change that we've really seen is that litigation is being used as a tool to inflict pain on the press," says Monika Bauerlein, CEO of the progressive investigative magazine Mother Jones.

Her publication has experienced it firsthand: In 2012, Mother Jones wrote a big piece on billionaire Idaho donor Frank VanderSloot, with the accusation that VanderSloot had "outed" a gay reporter by taking out a full-page ad that pointed out his sexuality. The story wasn't perfect.

"We actually published a correction to the initial story that really did need to be corrected and clarified," says Bauerlein. "But then we endured three more years of litigation after that."

Eventually, Mother Jones won. Although the judge accused Mother Jones of bias, she also concluded that the disputed claims were substantially truthful or open to interpretation.

And here's the cruel part of it: Officially, VanderSloot was asking for less than $75,000, but even though they won, Bauerlein ended up with $650,000 in legal fees.

"We would have to put a giant asterisk on our reporting, and publicly say that reporting that we knew to be truthful was untruthful" if they had settled the suit and paid VanderSloot, says Bauerlein. "Our reputation, our commitment to the truth is all we have."

But she also knows that some journalists don't have a choice. Some outlets are owned by corporations or are more concerned with the bottom line than truth, fairness and other journalistic principles. Other bloggers and reporters take down their reporting because, she says, "whether it was truthful or not, they couldn't afford the cost and strain of proving it."

Andrew Scott has not returned calls seeking comment. Regardless, Druzin says, "it's important for us not to be intimidated by bullies like this."

Hurst, who himself is in a messy defamation lawsuit battle involving a former state legislator and an outspoken Freedom Foundation critic, thinks the trend is going to be even worse in places like Idaho.

"There's more at stake," Hurst says. "There's more money, there's more power, there's more prestige. There's folks who want to get other folks to sit down and shut up."

But suing people to shut them up can just as easily elevate the issue. Actress Barbra Streisand's attempts in 2003 to get a photograph of her home suppressed backfired so spectacularly that the phenomenon was given a name: the "Streisand effect."

"I love Heather, but stuff like this is just a tool to get people to stop talking about stuff," says Hurst. "It usually doesn't work. The internet is forever. That image is forever." ♦