About 70% of Washingtonians will need long-term care at some point in their lives, according to research by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Long-term care might not be a stay in a nursing home. It could involve transportation help and grocery delivery for a middle-aged adult recovering from an injury. It could include in-home safety renovations for someone fighting an illness. It could be a part-time caregiver helping ensure someone gets showers and medications on time.

However, most people in the state are not planning for long-term care costs.

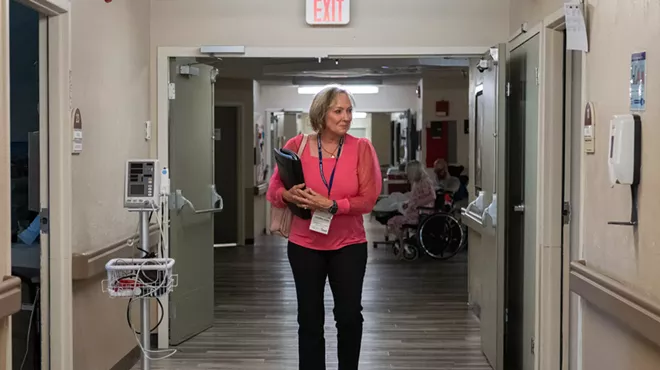

"There's a little bit of a misconception that Medicare covers long-term care, but it only covers short-term nursing facility stays. Most long-term care is usually in people's homes with family caregivers," says Lynn Kimball, executive director of Aging and Long Term Care of Eastern Washington (ALTCEW).

"The other biggest public program is Medicaid. Medicaid will cover long-term care in in-home settings, assisted living, adult family homes and nursing facilities, but it requires people to spend down their income and assets in order to qualify," Kimball explains.

Washington state lawmakers created another payment option called the WA Cares Fund in 2019. Via a payroll tax that started in July 2023, workers in the state are required to contribute 58 cents for every $100 earned into the fund.

After contributing for 10 years, state residents, regardless of how old they are, can access total benefits of up to $36,500 (an amount that's expected to increase over time with inflation) should a long-term care need arise. According to ALTCEW, that amount would currently be enough to pay a part-time caregiver for one to two years or cover the cost of a wheelchair and a few modest home renovations.

The WA Cares Fund has been unpopular with many residents. In November 2019, about 63% of voters who weighed in on an advisory measure told state lawmakers to repeal the bill that created the fund. The program's original start date was then delayed 18 months, during which time workers were given the choice to opt out. Close to half a million Washingtonians chose not to participate.

At the end of 2023, the citizen action group Let's Go Washington (financed by hedge fund manager and part-time farmer Brian Heywood) collected over 400,000 signatures to put an initiative on the upcoming Nov. 5 ballot that would alter the WA Cares Fund rules.

Initiative 2124 will ask voters if the WA Cares Fund should instead be an elective, opt-in program that also gives workers the option to opt-out at any time.

Supporters of the initiative, including Republican state Reps. Mary Dye of Pomeroy, Leonard Christian and Suzanne Schmidt of Spokane Valley, Mike Volz and Jenny Graham of Spokane, and Joe Schmick of Colfax, say that the tax puts too much financial burden on someone living paycheck to paycheck.

Currently, someone making $50,000 a year pays about $24 a month into the fund, or $290 annually.

Critics of WA Cares Fund also say the current lifetime maximum benefit of $36,500 per person is inadequate. According to AARP, the average cost for a year of in-home care in 2021 was $42,000.

Originally, the benefits were not portable, meaning people who work in Washington but live in or move to another state would not be able to access them. However, Washington lawmakers passed a new law this year that will offer the option to remain in the program if someone leaves the state.

Organizations opposed to I-2124, like the AARP and the Washington State Nurses Association, say that making the contribution voluntary would effectively eliminate the program.

According to an actuarial assessment by Milliman, an independent risk management firm, a large pool of people paying in is necessary to keep the WA Cares Fund solvent and its premiums low.

The more people who opt out, the higher the cost to participate becomes, which encourages even more people to drop out, Kimball says.

If the WA Cares Fund were eliminated, private long-term care insurance would be the only other option. Less than 10% of adults can afford it, according to the Washington Association of Area Agencies on Aging.

Those who buy private long-term care insurance are usually 50 to 79 years old. A 65-year-old single man pays an average of $1,700 annually for $165,000 in benefits, while a 65-year-old single woman pays $2,700 on average, according to the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance.

For those unable to pay for insurance or professional care, long-term caregiving often falls to friends or family members who bear the financial burden in other ways. Caregiving most often falls on women, many of whom give up their jobs to care for aging family members, says Ai-jen Poo, executive director of Caring Across Generations.

AARP Washington reports that there were nearly 820,000 unpaid caregivers in Washington in 2021. They worked nearly 770 million hours for free, valued at $16.8 billion.

Cynthia Stewart of the League of Women Voters of Washington worries that eliminating the WA Cares Fund will not only decrease women in the workforce and widen the gender gap, but "harm the majority of voters," who, even if they are part of the 30% who never needs long-term care, will probably end up shouldering the burden for someone else. ♦

Editor's Note: On Sept. 5 this story was corrected to explain that the benefits originally were not portable to those who leave the state, however Washington lawmakers changed that this year, allowing people to maintain coverage if they move or retire somewhere else.