As we continue to mark the Inlander’s 30th anniversary, every week we’ll look back at a different article from years past. This week, we’re rerunning a piece originally published on Dec. 18, 2003 and written by Ted S. McGregor, Jr. Also, watch for our 30 Years of Inlander feature every week in the paper through Oct. 12.

I. From a Tiny Spark

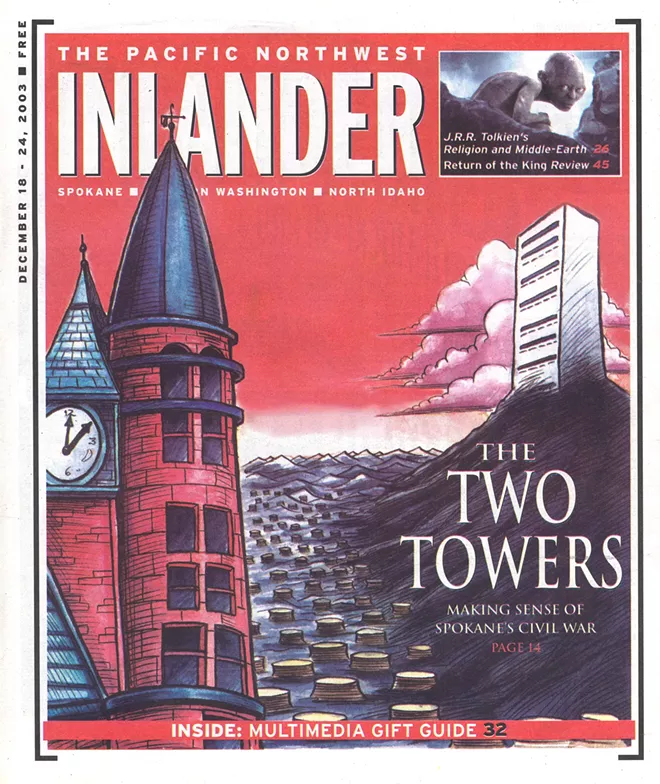

For the past seven years, two towers have loomed large over Spokane. In their shadows, war has been waged — a political civil war. At Riverside and Monroe sits the Spokesman-Review’s Red Tower, headquarters to the media and real estate holdings of Spokane’s Cowles family. At First and Wall, Metropolitan Mortgage’s White Tower rises, housing the Sandifur family’s financial services operation. Both structures are highly symbolic.

When the Review tower was built by Portland-based newspapermen in the early 1890s, it was so grandiose it literally bankrupted them. Stepping in to pick up the pieces was a newcomer to Spokane, W.H. Cowles, whose acquisition was the first of many that made his family among the richest in the Western United States. Today, the Red Tower is a symbol of the business and social elite that have led Spokane for more than a century: call it the headquarters for the establishment.

In the mid-1990s, when Met Mortgage was doing better than ever, it paid cash for one of Spokane’s tallest buildings — letting the city know how big the billion-dollar-plus company really was. It has come to be seen as a beacon of defiance in the face of Spokane’s cliquish past: it’s the reform movement’s spiritual — and financial — center of gravity.

For years before the war got underway, the two sides were already at odds. The establishment viewed the reformers as “naysayers,” in the terminology of Spokesman-Review Editor Chris Peck, useful for nothing more than stifling progress. Meanwhile, the reformers viewed the establishment as running roughshod over the community for private gain — all with the city government’s stamp of approval. Still, all-out political war didn’t start until 1997, when the controversy over redeveloping River Park Square lit the fuse on a big fat stick of political dynamite.

Sometimes the tiniest spark can become a devastating blaze. Other times, sparks burn out in seconds. It’s hard to tell one spark from another until some time has passed. When Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was shot in Serbia in 1914, it seemed like an isolated tragedy. Historians, however, have viewed that event as the spark that ripped open old political wounds, reviving nationalism, igniting World War I, which led to World War II, which led to the Cold War, and so on.

The sparks that flew on Jan. 27, 1997 in the Spokane City Council chambers started Spokane’s civil war. That Monday night, the council formally voted to become partners with Spokane’s Cowles family on a downtown redevelopment project. The city would lend its credit to the parking side of the project. Looking back, conditions were ripe for those sparks to become a full-blown conflagration. After that night, everyone found out what can happen when you don’t address long-festering problems in a community: They can erupt. In Spokane’s case, the end result was as close to a revolution as you can get in this day and age.

By that evening, the city council had already determined it was going to pass the partnership ordinance as an emergency, preventing voters from having a say on the project. Criticisms and concerns raised by citizens and business owners were not addressed; a council-requested, independent report raised even more criticisms, but it had only been delivered to council members a few hours before the vote. The city’s newspaper did not counsel caution in the face of the questions raised; instead, its editorial page supported the efforts of its owners and their plans to maintain their real estate’s value and “save” downtown Spokane.

There was also a lot of optimism in council chambers that night. Finally, the establishment’s supporters of the plan said, Spokane was going to take steps to save what was left of downtown and prevent it from dying out, like many cities’ downtowns had done.

But for those who viewed Spokane’s city government as detached from the people — a point already proven by other unpopular projects like the Lincoln Street Bridge and the waste-to-energy plant — that night‘s meeting only confirmed everything they already believed. And having the city contribute nearly $30 million to the deal (as the purchase price of the garage) also confirmed their opinion that the Cowles family used Spokane as just another way to make money.

But from early on, it was apparent that this was about a lot more than just a real estate deal. River Park Square was the opening the reformers needed to not only bring the changes they thought city government needed but also to break the Cowles’ grip on the city.

In the weeks following the council’s decision, many were outraged. On the scale of outrages, however, this $40 million problem (as some estimate the city‘s exposure) isn’t all that extraordinary. Nationally, you’ve got Enron and Wall Street conspiring to rip off investors and pensioners. And lobbyists for business now simply write the legislation that affects them. Regionally, you’ve got the citizens paying for not one but two stadiums for Seattle sports teams. And in Spokane, if the state of the streets isn’t bad enough, the social situation is tragic, with homeless teenagers — some with kids of their own — as living proof. But none of that has elicited the kind of response that the Cowles’ plan for downtown did. (But then, who ever thought President Clinton’s intern troubles would consume the nation’s attention for months on end?)

Whether the cure was worse than the illness is not the point of this analysis, however. What’s done is done. This story is about what this war has cost, what good has come of it and what can be learned. But before we get to that, it’s important to appreciate the people and ideologies that created so many sparks in the basement of city hall all those years ago.

II. Heroes and Villains

Sometimes a spark catches fire precisely because of who created it. Betsy Cowles is the fourth generation heir to her family’s fortune — a fortune raised largely in the Inland Northwest. To give you an idea of just how upper-crust she is, her stepfather is Punch Sulzberger, former CEO of the New York Times and one of the most prominent men in the world. During the height of the struggles, she was also a mother to two young kids and the decision-maker on the mall, among other companies. She became the reformers Public Enemy No. 1, but she says that hasn’t dulled her commitment to Spokane.

“We’ve been here 100 years, and we plan to be here another 100,” says Cowles. “So it’s not about what happens in the next two years; it’s where do you want to be in the next 10 or 15 years?

“From the bigger perspective,” Cowles continues, “we have emerged as a city that’s on the national map. In this day and age, you can’t be an also-ran. River Park Square has been a success. Despite what was happening in city hall, Spokane has made some big steps forward.”

To her supporters, Cowles has been a hero. After all, she came back to Spokane to carry on her family’s longstanding commitment to the city and region, as business owners, philanthropists and civic leaders. Instead of choosing a safer or more lucrative investment, she put together a real estate deal offering what she has called marginal returns in order to save downtown Spokane from ruin. And for this, people tar and feather her.

But to reformers and other critics, Cowles is just the latest in too long a line of corporate barons who have fattened their bank accounts on the backs of poor Spokane. To boost profits on this deal even more, she pumped up the numbers and arm-twisted the city council to make a gift to her mall project under the guise of buying the parking garage. And now that the air has gone out of those pumped up projections, she says a deal’s a deal and the city is left holding the bag.

But the reformers had a polarizing figure of their own. In those early months after that cataclysmic vote, legal activist Steve Eugster filed lawsuits aimed at declaring the city’s participation illegal. Born into a family of over-achievers (his brothers are an MD and a CEO), Eugster has one of the city’s sharpest senses of socioeconomic justice. He uses the law as his sword as he has slashes away at the foundations of a system he has long viewed as a plutocracy — a government by the elite. But like his nemesis, there were two distinctly different views on his efforts.

Eugster was the first person to stand up to the establishment and fight them at their own game, many thought. With the brains to counter the Cowles’ plans to bilk Spokane, his supporters were emboldened by his public comments. Nobody had ever said this kind of stuff before. In finally speaking the truth about what was going on in Spokane, he became the defender of the defenseless.

But plenty of other people saw Eugster as never having met a lawsuit he didn‘t like. And his legal actions were just costing the city and the Cowles unnecessary time and money. Here we are at this crucial moment, downtown boosters might have said, saving downtown from certain ruin, and Eugster is screwing it all up. Even after he swore to do his best for the city as a member of the council, he continued to file lawsuits against the city.

Whichever portrait is more accurate isn’t as important as the fact that Eugster became a one-man political movement.

“There were times when I was stirring it up quite a bit — and intentionally so,” recalls Eugster. “At the time it was fun, but looking back on it, I wish I’d never done it that way. I’ve paid a hell of a price.”

From January 1997 until today, the struggle that raged on was made possible because Eugster fanned those sparks. But his one-man show soon expanded, and he wouldn’t have gotten far without the help of Paul Sandifur Jr., who lined up his company, Met Mortgage, on the political gridiron to restore balance to Spokane’s playing field.

“I’ve known Paul for a long time, and early on he was really part of the status quo,” says Eugster. “But at one point, he questioned whether that was good for the community. His support made all the different in the world for me; were it not for Paul, I never would have gotten on the city council. And I don’t think the strong mayor system would have passed were it not for Paul either.”

The Sandifurs and Cowles would appear to have much in common. As major local property owners, a thriving city is crucial to either’s investments. Betsy and Stacey Cowles, brother and sister, and Paul Sandifur Jr. were born into privilege, but with other options before them, they chose to work in the family business. They are major benefactors of the arts, and they would say that they only have the city’s best interests at heart. The war seems to have hurt both of their businesses.

There are persistent myths about both camps, too. Some believe the Cowles family runs Spokane like some kind of plantation. This is an appealing storyline, but the problem is that there doesn’t seem to be much evidence of it. Back in the 1950s and ’60s, you could prove this theory. But even by Expo ’74, the Cowles’ backing of public financing of the world’s fair couldn’t win a citywide vote. And while their candidate endorsements used to be a one-way ticket to city hall, more often than not they’ve had a hard time convincing voters to go their way over the past decade. William Cowles III passed away a few years before the River Park Square plans emerged, leaving the heavy lifting to his children Stacey and Betsy earlier than anyone had planned.

Another myth about the establishment was that it was a pervasive network of like-minded movers and shakers — adding up to a mechanism that could turn the levers of progress whenever it pleased and without detection. But what might have looked like a clever conspiracy to some could just as easily be described as a garden-variety good-old-boys network nearing the age of retirement. The establishment exists in a kind of Babbit-esque go-along-to-get-along way, but to call it organized is a stretch.

And the reformers may not have been quite the populists they advertised. Often portrayed as the voice of the little guy, the truth is that the reform movement was really made up of a small cadre of moneymen (Sandifur), political strategists (like Met Mortgage vice president Erik Skaggs) and citizen activists (Eugster, Steve Corker, John Talbott and Cherie Rodgers).

While some reformers liked to say Spokane’s civil war was a fight between the haves and the have nots, it may have been more accurately described as a struggle of ideology, waged by Spokane’s two superpowers.

Most real wars are championed by political leaders, while everyday citizens are often more ambivalent when costs are weighed against the benefits. That was true in Spokane, where the battle was never really won by one side or the other. Instead, voters tiptoed through the political minefields and dictated the outcome through a series of momentous elections.

While reformers and the establishment saw the struggle in clear black and white, the citizenry seemed to appreciate the gray areas — doling out electoral victories and defeats to both sides. These are the people who go to the movies at River Park Square and don’t much care how the garage got financed; or the people who go to a show at the Met and don’t think twice about the politics of the person who gave the theater to the city.

Some might view these kinds of people as apathetic — part of the problem. But perhaps they were the smart ones, because the costs of being involved in Spokane’s civil war have been profound. Not only are the legal bills related to the parking garage mess still mounting (about $3 million so far for the city of Spokane; Cowles says her legal bills are in the millions, too), but the attention that has been paid to the problem over the years has been costly, too — preventing elected leaders from devoting more time to other challenges.

“[The controversy] has crippled the city’s efforts to get anything done,” says Mayor-elect Jim West. “It’s created distrust; it’s created this whole atmosphere of incompetence. When you have that kind of reputation, it’s tough to get initiatives going.”

Institutions have taken a beating, as well, with the traditional authority of everything from city government to the daily newspaper being called into question. And the war has created plenty of human victims. Political careers were cut short, reputations were tarnished (or worse), people’s personal lives have suffered and some may still have even bigger checks to write, as the River Park Square legal mess winds its way to a conclusion. As for the citizens, cynicism may have reached an all-time high.

Cowles says the fight has proven to have been counterproductive: “In Spokane, we’re too small of a city to have factions. Maybe the community has finally gotten tired of getting caught up in all the little stuff; we’ve got to think bigger.”

“I’m pretty hurt by it all,” says Eugster, “I’m somewhat decimated. But I’m not down and out because I’m still advancing ideas that the community needs.

“Maybe my style will change,” adds Eugster, pledging to continue as a community activist after he leaves the council, “but I can’t change the truth of what I’ve got to say.”

But nearly seven years after it started, all signs point to the war being over — for now, at least. In a few days, when Eugster and Corker step down from the city council, joining Talbott in retirement from politics, the reform movement that once ruled Spokane City Hall will be nearly gone. Only Rodgers remains. Many of the city officials in charge when the parking garage plan was adopted have left or been fired. And the money that fueled the reformers’ rise to power appears to have dried up, as Met Mortgage is facing significant financial challenges. (Met’s troubles came to light only recently, when the firm was reprimanded for unethical business practices — the same charge many of the reformers have made about Cowles’ business practices. The charge of unethical business practices is just that, however: an allegation. In its acceptance of the fine, Met did not admit any guilt.)

Eugster says that while the fighting may have subsided, change will continue to come to Spokane. “The reform movement is just beginning to take hold,” he says.

Whether it’s the beginning or the end, the past seven years have been a wild — and expensive — ride. And as in most wars, pivotal battles were fought, with each side experiencing both victory and defeat.

III. Trench Warfare

With the election of 1997, Spokane’s civil war really got underway. Talbott, a leading critic of city government, challenged incumbent Mayor Jack Geraghty, who was instrumental in shepherding the garage deal through the city. Talbott turned the race into a referendum on River Park Square; you didn’t get to vote for it the first time, he seemed to be saying, so you can sound off now. Talbott won by fewer than 200 votes. Despite throwing its editorial weight behind Geraghty, the Review couldn’t sway the citizens, who were clearly upset about how the city was doing its business.

But that election also marked the successful entry into city politics of Met Mortgage and Sandifur. Talbott’s election was a turning point for the reformers — and a wake-up call for the establishment. With Rodgers already on the council when Talbott took office, the reformers were only two votes away from taking control of the city.

In late 1999, as the parking garage deal was just being finalized, reform candidates Eugster, Corker and David Bray ran for city council. If any two of them won, the reformers would take control. Again despite the Spokesman-Review’s efforts to persuade voters via election endorsements, the reform party won big, not only in getting Eugster and Corker elected (with Met Mortgage’s financial backing), but also in the passage of the Eugster-authored strong mayor initiative. Things were about to change.

A few months after that election of 1999, with the parking garage only having been open for about six months, the facility’s performance was not even coming close to what city officials and mall owners had expected. The thing was basically bankrupt right out of the starting gate, confirming what some of the deal’s earliest critics — including people who now ran the city — had predicted. So with a big problem looming for both the city and the Cowles, the new majority got a test of leadership: It had to decide how to solve this emerging mess. Although some overtures were entertained between Corker and mall manager Bob Robideaux, the reform faction in control of the city did not work with the city‘s old partner in the deal; instead, they chose to file a lawsuit charging that the city had been defrauded by the Cowles and others.

Eugster says his own efforts to solve the problem that summer with former city manager Terry Novak and the city’s outside attorney Roy Koegen failed because of crossed wires between the two competing plans. But he says even at that time, he knew legal meltdown was coming: “You could see where it was going at that point, to where it is today.”

There’s no telling whether a workable solution could have been hammered out that summer, as the two sides didn’t trust each other and the overall problem wasn’t fully understood yet. But within a year, the problem became a legal free-for-all, as the investors who bought the project’s bonds sued, turning lots of nervous observers into defendants. The Cowles wound up firing back at the reformers, naming some of them in a lawsuit alleging that they had damaged the mall by bad-mouthing it.

The war of words was hot that summer, and Sandifur even had local media helping push his cause. He was the first one to fund Camas magazine, an online publication devoted to uncovering more information about River Park Square (although the Web site later dropped his patronage). And Met Mortgage was the biggest advertiser in the Local Planet, which offered a steady diet of anti-Cowles content.

While the reformers’ charges of fraud that summer may be revered as their most principled stand, it was also the beginning of the end for the movement. After the summer of 2000, voters became less inclined to follow the reformers, who appeared to be better at knocking down walls than at governing once inside the keep. Besides, by then, the big reform — switching the city over to the strong mayor system — had already been accomplished due, in large part, to the reformers’ efforts.

While the reformers and the establishment fired their volleys back and forth during the summer of 2000, the citizens were growing weary of it all. City council meetings became the butts of jokes around the coffee urns of the city every Tuesday morning, even though some of the exchanges were too personal to be very funny. Come November, the voters were presented with a third way, and they took it, choosing John Powers to be the city’s first strong mayor. Running without ties to either of the city’s de facto political parties, Powers ended Talbott’s tenure. The reformers wound up with just one year as the majority on the city council.

While Powers may have had the citizens with him, and his election did mark the end of the reform party’s run of electoral success, his attempts to negotiate a path between the superpowers were frustrated. The reformers, from the start, opposed Powers almost as bitterly as they did the Cowles. Why is somewhat puzzling, since Powers wound up taking a harder-than-expected line against the Cowles on the garage deal. Still, the reformers changed their focus: Instead of spending their energy on reforms, much of their effort was spent on thwarting Powers.

“Met was looking for somebody to discredit the developer,” Powers recalls of his three-year term. “That doesn’t solve a problem. That’s about yesterday’s hard feelings. By the spring of 2002, it was clear that one of [Met’s] new objectives was to defeat me because I hadn’t signed on. I heard it from the mayor in Post Falls, and from Sandifur himself, and from Corker and Rodgers. I think they’re just people who want to control.”

Powers first act of business was to take the reformers’ No. 1 issue — River Park Square — off the front burner. He removed the charge of fraud in the city’s case, and the issue cooled to a simmer, never again to be as politically volatile as it was in 1998-99. Still, he never could shake loose a compromise and solve the problem.

“I underestimated the sense of emotion and pride and heels dug in,” says Powers. “I just saw this as a business problem that could be solved.”

So by the time the mayoral election rolled around this past August, the River Park Square controversy was not the race’s defining issue — a political milestone, as the issue had overshadowed the city’s politics for nearly a decade.

By this time, the reform party was in disarray; Rodgers, Eugster and Talbott were all endorsing different people for mayor. Corker was a candidate for mayor, but he didn’t make it out of the primary; instead, a peripheral reform figure, journalist/pundit Tom Grant, wound up losing to West in the general election. Met Mortgage’s last successful political effort was to oppose Powers, who did not make it out of the primary.

State Sen. Jim West borrowed from Powers’ playbook, however, in trying to steer clear of the two warring tribes. He did win the Review’s endorsement, and Sandifur did not actively oppose him. But unlike Powers, who never could quite establish a rapport with either faction, West has close, longstanding ties with both the Cowles and Sandifurs.

“I wanted to maintain relationships with everybody in this thing,” says West, “not choose sides.”

IV. Win, Lose or Draw?

All sides paid a high price for the struggles of the past seven years. Met Mortgage — the White Tower — faces an uncertain financial future, begging the question of whether its focus on local politics exacted a heavy price. And the Cowles — the Red Tower — have seen their reputation take a big hit. They’ve also seen their mall perform less well that they had hoped; even their newspaper has experienced big cutbacks for the first time in its history.

But both sides can claim victory, too. The Cowles got the public’s help for their garage (unless the courts rule otherwise), and their mall has both preserved the value of their downtown real estate and turned around a deteriorating downtown core. Cowles believes history will show her project was the right one at the right time.

“I’m sure when Expo ’74 was being put together, there was lots of controversy and angry opposition,” says Cowles. “Even afterwards there was controversy. But 30 years later, it still has a great legacy.”

And if the reform party’s primary goal was to open up the city, it succeeded. Now Spokane elects city council members by district, and the city is led by an elected mayor, not a hired bureaucrat. Eugster adds that the city’s political sensibilities have matured as well.

“People are much more understanding of vigorous debate than they were in the past,” says Eugster. “Some people will pooh-pooh it and say the council is dysfunctional, but that’s just the story fed by the newspaper.

“I don’t think America would have been America without its Civil War,” Eugster concludes. “We’ve got a sense of sadness and brightness because of it; there’s a humility and a hope.”

In the end, everybody won and everybody lost. Call it a draw.

“The town will never quite be the same, and I think that’s good,” says Powers. “It’s been a rough and difficult transition, but we’ve evolved to a new, more open and accountable, progressive city government. I think there are smoother waters ahead, and we’ve got some wind at our back.”

West, who’ll start testing those waters officially in just a few days, says he thinks the city is ready for some postwar reconstruction.

“When you make a mistake, you have to pick yourself up, dust yourself off and move on — take the corrective action and move on,” says West, adding that for too long now the city has been unable to manage the “move on” part of his recipe. “We’re still looking for the license plate of the truck that hit us.

“On the campaign trail,” West continues, “we heard over and over that we just need to get RPS behind us — in a way that protects the taxpayers — but we need to get it behind us. I told people the most important thing is that we never do it again, that we learn from our mistakes.”

Here are a few of those lessons that the city might have learned the hard way.

INCLUSION Much of the public outrage over the city’s decision to declare a state of emergency when it joined the mall project was because people were excluded from deciding. Critics felt like they were talking to a brick wall, as the city council was moving forward regardless of what anyone had to say. Others were just offended that “saving” downtown was not a collaborative, community-wide effort, but the plan of one property owner. Trouble could have been averted if the public had been consulted more honestly.

TRUST Perhaps the reason for not allowing for more inclusion is because the city and some of its elite essentially did not trust the citizens to endorse their plans. As a result, the citizens did not trust city government. What goes around, comes around.

COMMON GROUND It may be naïve to think that everyone around here could ever pull on the same rope, but it’s also naïve to think that if Spokane doesn’t get its act together, especially on the economic development front, it will somehow thrive in spite of itself.

While some partisans on either side may take pleasure in the misfortunes that have befallen Met Mortgage, the Spokesman-Review and River Park Square, they shouldn’t. The fact is, to keep Spokane from becoming an also-ran city, the Sandifurs and the Cowles — along with any private businesses or dynamic individuals capable of making good things happen — are crucial. Spokane needs all the help it can get. Met’s plans for the Summit property are exciting and much needed, as housing is a missing ingredient in the downtown picture. And the Big Easy project will be another gem in the local arts scene. River Park Square has been a savior for downtown, even though the district’s future is by no means secure. And the Cowles long-time commitment to Spokane has made a positive impact and needs to stay strong.

To recite the cliché, it’s about making the pie bigger, not fighting over the pieces we already have. And common ground is just that; the very term suggests there are areas not agreed upon — and that’s OK. Without an acknowledgement that it’s possible for people to disagree on some things while they agree on others, tribalism and distrust will persist.

LEADERSHIP Over the past seven years, the city’s lack of leadership has been very costly. Having no effective leadership led to a flawed deal on the garage in the first place; it led to not being able to solve the problem when it might have been solved in the summer of 2000; and lack of leadership has prevented the warring factions from recognizing their shared fates.

Of course, you have to want to be led, and while the people may have been behind Powers, neither faction was. Prior to Powers, the reformers couldn’t work with Geraghty; the establishment didn’t much care for Talbott.

West’s novel approach — against nobody, for everybody — is savvy because it seems to have won him the political high ground in a city where that real estate has been dearly bought. And most expect River Park Square — the albatross that has hung around the necks of his three predecessors — to be more or less settled within his first six months in office. Whether lasting peace is within his grasp, however, remains to be seen.

A few missteps, and West could start shooting off sparks of his own. Even though the political winds that have fanned the flames in past have died down, playing with fire, as Spokane has come to find out, is always dangerous. ♦