He was drunk and the kid was moving. That’s all it took for Adam Layton to flip a U-turn on Sprague Avenue just east of downtown Spokane last winter, primed to throw a punch.

Layton is a tough, streetwise 16-year-old who already has 20 tattoos and a handful of felonies. He was driving with some buddies and a girlfriend. They were all plenty buzzed, he says, cruising in a warm car on a dank February night. It was a good time. Layton, even months later, can’t explain what happened next.

“I saw some dude riding a bike, so I pulled up. I hopped out. And I hit him,” Layton says. “He dropped, and we grabbed his bike, threw it in the car and drove off.”

Layton is recounting this spur-of-the-moment punch-out in the library of Spokane County Juvenile Detention this summer. He’d just been sentenced and was a day or two away from being shipped off to pull two years in the state’s maximum-security juvenile prison, Green Hill, near Chehalis. It’s what’s known as a JRA, run by the state’s Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration.

Layton realizes this is a big break. After all, the state wanted to try him as an adult and send him to a penitentiary for nearly four years along with a first “strike” as a violent criminal. Three strikes and you get life without parole.

“I never thought I’d be looking at significant time for socking a kid and taking his bike,” Layton says.

His age is what nearly sent him to adult prison. Even though he is still a minor, the law didn’t have to consider him a juvenile any more. At 16 and 17, there is a lever that diverts juveniles automatically into adult court if they are charged with certain crimes. Crimes like first-degree assault with bodily harm.

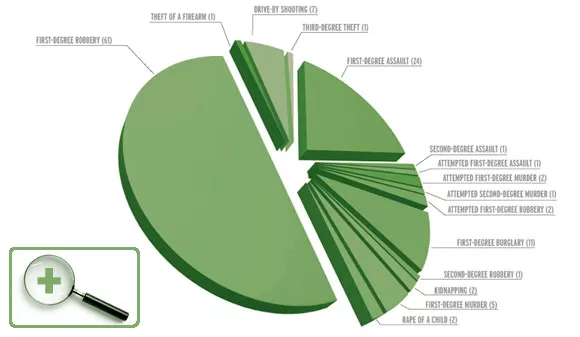

This is called “automatic declination.” It is little known outside the justice system and sends roughly 200 Washington teenagers a year into adult courts and — potentially — adult penitentiaries. As the term indicates, it happens automatically, without a hearing or any debate.

The idea is simple: Here is a list of crimes. Commit one of these and, if you are 16 or 17, you go straight to adult superior court, not juvenile court.

A prosecutor can decide to send the offender to juvenile court, but can’t be compelled by a judge or defender. “Prosecutors have the power of God,” one critic says.

The law was originally designed to punish the worst of the worst, but in practice that’s often not the case. Race, the strength of a defense attorney, the mood of a prosecutor and sheer luck can play a major role in deciding who is treated as a juvenile and who is not.

The stakes couldn’t be much higher for the kids involved: In the juvenile system, there’s counseling, school and a push for rehabilitation. In adult facilities, there’s punishment — as well as older inmates who, studies show, tend to exploit younger offenders.

Consider Allison Wessling, who at 17 was facing up to a 30-year penitentiary sentence even though she had no criminal record. Like Layton, she is another streetwise kid, but with no history of violence. Instead, Wessling’s legacy consists of truancy, running away and drinking.

In fact, she was planning on running away to California with a girlfriend in June 2009. She asked her friends to take her back to her dad’s house on Spokane’s South Hill so she could break in and collect her stuff.

“They cleaned the house out,” her dad says.

With money from the burglary and her Job Corps paycheck, Wessling and her older friends decided to go drinking. She purchased a half-gallon of whiskey, she says, but the others wanted beer.

At a north-side grocery, an older cousin shoplifted the beer. Then he pulled a gun on the way out when confronted by employees. Even though she had remained in the car, Wessling was considered an accomplice and so she, too, found herself charged with first-degree theft, first-degree armed robbery and unlawful possession of a firearm. Plus, there were as many as six first-degree assaults (from the gun-waving cousin) hanging over her head, she says the prosecutor told her.

Unlike Layton, whose prosecutor and defender eventually agreed to return him to juvenile court, Wessling took a plea deal for reduced time and has been serving her adult felony sentences in the Spokane County Jail, which she describes as “a dungeon.”

Layton’s and Wessling’s cases offer an unexpected peek into how the automatic declination process has crept away from original intent to safeguard society from young monsters.

In one case, it allows the system simply to give up on some kids and send them to penitentiary for no other reason than that people are tired of dealing with them.

In the other, youth are offered plea bargains for short sentences in county jails where it’s the worst of both worlds. They are a) not being locked away for many years to protect society, and b) receiving absolutely no rehabilitative attention.

With just shy of 2,000 troubled youth in Washington “auto declined,” as the phrase goes, in the last decade, some say there’s been mission drift.

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVES

Is it time to reassess automatic declination? A growing body of research into brain development is producing evidence (pdf) about adolescent behavior that parents already know: Teens do incredibly stupid things without thinking.

This is not willful behavior. The human brain itself is neither finished developing nor fully functional until about age 25. Teenagers make decisions with a brain that, largely, is impulsive, aggressive and has little concept of long-term consequences.

This research has become so solid that the U.S. Supreme Court has cited it twice since 2005 in rulings that have banned the death penalty and limited life without parole as sentences that can be given to juveniles.

Other studies show young offenders punished as adults have higher rates of re-offending than those in juvenile rehabilitation.

“I don’t see how we are doing anything for these kids,” by auto declination, says Kari Reardon, a Spokane County public defender. “Why do we want to create more FACT criminals?”

Research into brain development and recidivism has also led to a study in Washington that is calling for eight reforms in the state’s juvenile justice system, including abolishing automatic declinations.

It’s a reform that, The Inlander discovered, has a surprising level of local support.

“I wouldn’t object to that. It’s kind of a due process kind of question” for juvenile offenders, says Spokane County Prosecutor Steve Tucker.

"It makes no sense to send kids to adult prisons where they frequently learn how to be a better and more violent criminal." — Former Superior Court Judge Neal Rielly

After all, the goal of juvenile court “is still rehabilitation,” adds former Superior Court Judge Neal Rielly, who retired last month after 22 years on the bench, ending with a three-year stint in juvenile court. “It’s become a more adversarial system, but the mission is still rehabilitation. That’s the primary focus.”

There has always been a way for prosecutors to bring adult charges against a minor who has committed horrible crimes. These are called “discretionary declinations,” and a judge decides if the offender goes to adult or juvenile court after a hearing.

This is the only way declinations should happen, Rielly says.

In automatic declinations, prosecutors can detail aggravating factors — a gun was used, the victim was beaten — in the charges. There is no place for mitigating factors to be presented (until trial, if a trial happens at all).

One young man interviewed by The Inlander noted the stark difference. In adult court, he was portrayed as an awful person who needed to be punished for a string of serious-sounding crimes. In juvenile court, he was seen as a kid with a drug problem who needed help.

“If we are going to do declinations — and there is a place for them — there would be very few people I would decline on, to be honest with you, because I think it is usually a mistake,” Rielly says. “A judicial officer should be able to review the evidence and have a contested hearing where a prosecutor is arguing for it and a PD [public defender] is arguing the other way.”

“I think that sounds fair. I agree with the judge on that,” Tucker says.

“I don’t think it’s [automatic declination] being misused,” says Spokane attorney Frank Malone, who’s challenging Tucker in the November election. “Even if you have a first-time offender, if they do a serious, violent offense, you don’t want to lose control over that person in a few years. That’s the advantage of adult court.”

Which is the theory behind moving minors out of juvie — balancing the potential rehabilitation of an individual against the protection of society.

But in practice, youth who have been auto-declined are serving sentences that are, on average, a year longer than those convicted in juvenile court, says David Griffith, acting director of the Division of Institution Programs for juvenile prisons.

“There’s a study that shows if we take a juvenile and put him in adult prison, his recidivism rate is about 85 percent. If I keep him here as a juvenile — even if he is a jerk-off and not responding to our treatment — his recidivism rate is substantially less,” Rielly says. “Just on that alone, it makes no sense to send kids to adult prisons where they frequently learn how to be a better and more violent criminal.”

‘BEYOND HELP’

Adam Layton had a fistful of priors and had gotten into plenty of fights before he found himself on the brink of adult punishment this winter. When Layton was 10, his father was murdered. Later, a friend committed suicide, and last year a second one was stabbed to death with a steak knife in a north Spokane fight against five other kids.

Layton was a kid headed deeper into trouble, and everybody knew it.

The inexplicable punch he threw last February fits pretty neatly into examples used by researchers to illustrate the still-forming adolescent brain.

The punch was impulsive and aggressive. It was thrown without any reason or plan. As for the stolen bike: “We didn’t know what to do with it. We kept it in the garage [until] a detective came and got it.”

“When I first got that case, everybody had given up on Adam,” his public defender Jeff Leslie says. “He had so many assaults, they were thinking he was beyond help.”

However, unlikely sources stood up for Layton. There were the administrators of a juvenile facility, where Layton had earlier done time, who liked him and saw potential. The victim and the victim’s father also saw some hope in Layton and were agreeable to giving him another shot in a juvenile prison, Leslie says. Finally, the prosecutor sat down with Layton for a rare face-to-face and agreed to send his case back to juvenile court.

It doesn’t happen often. Out of the last 122 automatic declinations in Spokane County (going back to October 2005), only 14 young offenders were returned to juvenile court.

The Inlander has followed up by telephone at Green Hill. Layton’s voice changes, becoming noticeably enthusiastic, as he talks about attending school for the first time in years. And to find out that he likes it. He’s jazzed about learning, even taking classwork back to his cell. “I’ve never been in a real high school before,” he says. He notes, with some excitement, that he can get a diploma through Green Hill, not just a GED.

“And the diploma doesn’t say Green Hill. It says Chehalis School District,” Layton says.

He is also excited about opportunities to learn vocational skills and getting “real” jobs through the JRA system with the state Department of Natural Resources on tree-planting and fire-fighting crews.

“We offer something that is quite a bit different than what they might find in a [Department of Corrections] setting or a jail setting,” says Griffith. “Our setting is like a large campus designed for adolescents with a high school as opposed to GED. There are treatment programs designed for adolescents.”

The emphasis is on education and rehabilitation. The programs are staffed at higher levels than the DOC, and they are mandatory.

But it doesn’t mean life in a juvenile facility is a cakewalk. Green Hill has a reputation for assaults, and Layton quickly experienced it first hand.

Layton’s gang tattoos had initially won him allies at Green Hill from Spokane Sureños circles — trusted people to hang out with. But a counselor challenged Layton to walk away, and he did.

“Then one day, I was walking out of the bathroom and a kid ran up and punched me,” he recounts.

Next Page: Layton fights back. Plus, where do young offenders go?

Layton — and this astonished some people who know him — didn’t fight back. He threw the kid down onto a table and then, “I wrapped him up and waited for staff to come. Walking away is difficult.”

His decision impressed staff at Green Hill and Layton says he made a pitch to be transferred to a different JRA — where he would not have to keep fighting and with better school and job prospects.

“I’m trying to do better, man. I’m trying to get out and be successful. It’s got to start here,” Layton says. “It was very difficult to [break with the gang] because I’ve been around it so much.”

A couple of days after our telephone interview, a Green Hill program director called to say that Layton had been transferred.

COUNTY TIME

Meanwhile, The Inlander discovered an unexpected and disturbing aspect of automatic declination in Allison Wessling’s case.

Remember that only 14 of 122 auto-decline cases were returned to juvenile courts? Does this mean, we wondered, that Spokane County has sent up to 108 kids into penitentiaries in the last few years?

Not likely. When young offenders are convicted as adults, they are held in two of the juvenile prisons — Green Hill for males, Echo Glenn for females — until they turn 18 (21 in some cases), and then are assessed for transfer into adult penitentiaries. The two facilities have only 65 beds, combined, for auto-declines, Griffith says.

So where do all these kids go?

Emerging anecdotal evidence suggests that they are kept in county jails.

Sorting out the data in automatic declinations is frustrating, even to investigators and number-crunchers at the governor’s Office of Juvenile Justice and the state Sentencing Guidelines Commission.

In other words, nobody really knows how many 16- and 17-year-olds are pulling time in county jails.

Eight Reforms

The following are reforms suggested by the Washington Coalition for the Just Treatment of Youth.

1. Eliminate life without parole as a sentence for adolescent offenders.

2. Create a juvenile-specific review process for periodic review of youth sentenced in the adult system.

3. Eliminate automatic decline.

4. Set 15 as the age below which no adolescent may be transferred to the adult system.

5. Create a system to transfer youth back to juvenile court when appropriate.

6. Require that youth be held in juvenile facilities pre-trial and post-conviction until age 21.

7. Refocus efforts on prevention and rehabilitation.

8. Ensure policies and practices are culturally competent and gender-responsive.

“You should tell your readers these numbers are all estimates,” says Keri-Anne Jetzer, a research investigator with the Washington Sentencing Guidelines Commission.

Like Jetzer, “We have not found a single agency that tracks these numbers,” says Beth Colgan, attorney with the Columbia Legal Foundation in Seattle.

“I am not familiar with the number of auto-declines serving time in county jails,” Griffith says. He hopes it is not becoming an institutionalized choice. “It’s not set up for long-term treatment. It is more punishment-oriented.”

County jail is where we met Allison Wessling, wearing a dark green jumpsuit and with dark, rumpled hair behind the thick glass in a claustrophobic visiting booth. She has distinctly pale skin that hasn’t felt sun in over a year.

Wessling and her pals, after the beer run fiasco, traveled to Worley in North Idaho. She was planning on running away to California the next morning with a BFF who lives on the Coeur d’Alene rez, but they caught the attention of security at Coeur d’Alene Tribal Casino and were quickly detained.

“[Security officers] were driving around the parking lot looking for anything suspicious and we were high and didn’t realize how stupid we looked,” she says.

She was eventually taken back to Spokane, where she was surprised to be booked into the jail and housed in the women’s maximum-security unit known as the Dog Pound. She has been in the jail 14 months, with two to go.

“Frankly, I was scared,” she says, when a prosecutor outlined her adult charges and later told her that she could face six additional first-degree assault charges, plus gun enhancements — a potential 30-year sentence — unless she took a plea deal.

Wessling pleaded guilty to three charges, reduced from the original but still Class A felonies. She gets out just before Halloween.

When she first went in, in June 2009, Wessling says inmates had two hours of free time in the mornings and two more at night. Now, with so many cutbacks to jail staff, inmates are typically out of their cells only 80 minutes a day. Other kids we’ve talked to note that the jail is frequently locked down so the undermanned staff can keep a lid on things.

There are some paperback books she can check out from a shelf in her unit, Wessling says. But no TVs, no school, no vocational training, no substance abuse counseling.

Wessling assessed her future in an interview conducted via a scratchy intercom.

“Being in a facility surrounded by people who are doing bad … that’s all they talk about, that’s how they live. You are surrounded by it every day. All they do is talk about their cases or smoking meth or robbing,” Wessling says.

Wessling says she’d like to stay out for good, but she also offered a critical self-examination.

“The thing with me is, I’ll do good, or I’ll try to do good and I’ll not get what I’m going for and I’ll get discouraged and fall back into what’s comfortable,” she says.

Colgan from the Columbia Legal Foundation says kids doing sentences in county jails are serving time in the worst possible way for juveniles. Even penitentiaries have clubs and counseling and classes.

And sentences being plea-bargained down to a year or less points out a failing — or a misuse — of the automatic declination process.

“This begs the question: If the sentences are that short, why are they not in juvenile court in the first place?” Colgan asks.

Youth in county jails also come out with adult Class A felonies — Wessling will have three — that never can be removed from their records. Juvenile Class A felonies — thanks to a reform pushed through the Legislature last year — can now be sealed after five years, in most cases.

Again, Colgan asks: “Do we want to make it difficult for kids to get a job or go to college? Do we want to make it difficult for them to be successful when they get out? Is this really serving the public interest?”

IN THE BEGINNING

The creation of a separate juvenile justice system in Washington in the 1970s was all about rehabilitation. Kids were treated differently than adults, younger kids differently than older kids. The focus was more on education than retribution. It was the New Testament God, not the Old.

Then came Columbine and Crips and Bloods and — thanks in part to breathless media coverage and political grandstanding — lawmakers promised to crack down on violent youth. People became afraid of teenagers.

All across America in the 1990s, laws allowing automatic declination were passed. Suddenly it was OK to toss minors into penitentiaries. Arizona, in 2008, charged an 8-year-old as an adult for two murders.

The youngest in Washington was 11. A 13-year-old in Washington was sentenced to life without parole.

A recent story out of Colorado noted that the juvenile crime rate in that state didn’t increase a whit during a period of high-profile media coverage of violent youth crime in 1993, dubbed by the media as the “summer of violence.”

In Washington, the overall juvenile crime rate has been declining since 1994, the same year the Legislature passed the Violent Crimes Reduction Act, which allows for automatic declination.

So it’s working, then?

“The recidivism rates are going through the roof,” says Bonnie Bush, administrator of Spokane County Juvenile Court Services. “We are maybe doing more harm sending kids over to the adult side.”

When the Violent Crimes Reduction Act was passed, “The Legislature saw this as an opportunity to say, ‘We are tough on crime’ without thinking through the impact of this,” says George Yeannakis, attorney with Team Child in Seattle and a leading voice for juvenile justice reform.

Legislators initially created a short list of violent crimes in which any kid 16 or 17 who was charged with one of them would go straight to adult court. The law was expanded in 1997 by adding more crimes to the list.

At least the 1994 law was heavily debated in the Legislature, was strictly limited and was passed as an experiment, Yeannakis says. The 1997 expansion passed with little debate and no evidence of what effect, if any, the law had on crime, he says. (In Idaho, juveniles can only be transferred into adult court for a short list of severe crimes.)

By 2000, Yeannakis adds, studies began to show that harsher adult punishment for juveniles was not working.

“Everybody knows that kids are different. I think the Legislature knows this, too. The study had a lot of disclaimers, but it said transferring more kids into the adult system did not have an impact on [reducing] violent crime,” Yeannakis says.

At the same time, research across the nation continues to show that human brains are not fully developed until we reach our 20s.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a decision that banned death penalties for juveniles, wrote in the majority opinion, “From a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”

The justices, according to Colgan, the Seattle attorney with Columbia Legal Services, “drew three distinctions between adolescents and adults. First, the court recognized youth are comparatively more immature than adults, [which] may lead to reckless behavior. Second, the court noted that youth are more susceptible than adults to negative influences such as peer pressure. Third, the court recognized that personality traits of youth are in flux, leaving time for additional character formation.”

Colgan was writing the above in a 2009 report (pdf) assessing the state’s juvenile justice system and calling for specific reforms. (See “Eight Reforms" sidebar.)

More recently, the U.S. Supreme Court also banned juveniles from being sentenced to life without parole for crimes other than homicide.

“Chief Justice John Roberts said that, because of adolescent brain development findings … he agreed with four others that you can’t put a kid away forever,” Yeannakis says. “We’re getting that kids are less developed than adults.”

Even as research showing that adolescents have very different decision-making capabilities than adults is becoming unassailable — even to the conservative chief justice — attempts to abolish automatic declines seem far away in Washington.

“What we run into when bills are offered to change the system is an almost reflex action of many legislators who do not want to be seen as soft on crime,” says Democratic Rep. Mary Lou Dickerson of Seattle. “There is a failure to recognize that although these juveniles may have committed very serious crimes, it’s not the same as a 26-year-old committing those crimes. … Kids are different than adults.”

"I sat and listened to the charges and said, 'You guys must have the wrong person. I'm not that kind of guy who would do that stuff.'" — Justin Cairns, who was arrested at 16

SMALL-TOWN BOY

Justin Cairns is 19 now, a big kid with a friendly face who carries himself with the sort of demeanor that prompts observers to think: “Nice Young Man.”

But Cairns didn’t come across as such a nice kid nearly three years ago when a prosecutor read off a list of severe adult crimes that carried, he learned to his shock, a sentence of eight years in state prison.

Before then, the 16-year-old farm boy from Reardan (who lived with his grandparents) had never before been arrested for anything. But in high school, he began to experience the more oppressive side to small-town life: “Too many people know your business.”

Partly out of rebellion, Cairns started buying — and later shoplifting— cough and cold medicine. After users chug a bottle, the active ingredient, dextromethorphan, creates a long-lasting high that brings an expansive sense of well-being, hallucinations and an altered sense of time.

“It’s powerful. I saw it as this ‘next-world’ thing,” Cairns says. “I went downhill really fast.”

Next Page: A Pullman woman has to fight the system to save herself.

One night in mid-September 2007, he drove off in his grandfather’s car — an aging four-door Chevy Lumina — and went to an uncle’s house on a different part of the same large farm.

“That night I wanted money, so … I went to my uncle’s house. You can easily find the key to open the door, but I decided to be crazy and bust a window and go in that way,” Cairns says. He took money and, impulsively, one of his uncle’s guns.

“Later that night we got two of my other friends and we went out in this wheat field,” he says.

They started spinning brodies, wahooing and shooting the gun off into the night. One of the bullets hit a house.

When he showed up at his grandparents’ house the next night, “there were five cop cars in the driveway and I thought, ‘Wow! They really don’t like people taking other people’s cars.’”

Cairns was booked into juvenile detention, but the next afternoon, he was handcuffed and walked across the street to the jail because, one of the officers told him, of a thing called “auto declination.”

At his first court appearance, “That was the first time I heard about me being charged with drive-by shooting, theft of a firearm, residential burglary and taking a motor vehicle without permission,” Cairns says.

“I sat and listened to the charges and said, ‘You guys must have the wrong person. I’m not that kind of guy who would do that stuff.’”

Cairns remained in solitary confinement for 23.5 hours every day for the next 10 days, he says. For their protection, juveniles are often isolated from general inmates for long stretches of time.

Still, some inmates, while out for exercise, would peer into his cell. “I was so glad there was a door,” he says.

“There is a lot of fighting in there. People are fighting or getting beat up or trying to get into the staff room … I felt like I was thrown into a dungeon,” he says.

About this time, public defender Kari Reardon took over his case from a private attorney and got him transferred the next day to Martin Hall, a holding facility for juveniles from around Eastern Washington. And, though it took seven months, she eventually got his case back to juvenile court by repeatedly citing his lack of a record.

“She is an amazing attorney,” Cairns says.

He was sent to a juvenile facility that specializes in drug counseling. Nine months later, he went to a group home in East Wenatchee. On March 18, Cairns was released with no probation or parole and is working at a McDonald’s, the one place that hired him despite his felony record.

“The difference between juvenile and adult court is night and day,” he says. “The adult side looked at my rap sheet and said, ‘We’ve got to punish this guy.’ The juvenile said, ‘This kid has a drug problem and he needs help.’”

KIDNAPPED

Meet Starcia Ague (pronounced “starsha ag-you”). She grew up in a crazy, broken, drug-addicted family in Olympia and was sent to live with her dad, who was a meth cook.

People would ring the doorbell all day and all night looking for drugs and Ague, then 13, did not have a bedroom like most kids. She was camped in the living room and was often the one who would open the door to greet the people who came to purchase her father’s potent drugs.

"What does it say when you are beating all the odds and they're still going to throw bricks?" — Starcia Ague, who did a "juvenile life" sentence and has since graduated from college.

“I figured,” Ague says, “that anybody who wanted to buy drugs bad enough would give me money.”

So young Starcia stood at the door and said, “It is a $1 charge for everybody who comes in.”

The thing is, she says, “people who sell drugs and buy drugs don’t carry dollar bills. I would get paid in $20s and $50s.”

Here is what she did with the money.

“I put it all in an account to go to college, but I was underage and had to have a cosigner.” One day, the police came for her dad and seized the savings account. “His name was on it and he owed $35,000 in child support, so I never seen any of it.”

She didn’t see it as a younger child, when she was living with her mom — an addict and prostitute who didn’t seem to care there was no food in the house, or that she never sent Starcia to school, or that the kids had head lice.

“I used to file CHINS petitions on myself so they would take me out of there” and place her in foster care, Ague says. CHINS denotes Child in Need of Services.

But the state social services have a policy that families do better together. And even though Ague is now a fierce, tough young woman in a gray, pinstriped power suit who has served a “juvenile life” sentence and graduated from Washington State University and testified about injustice in Washington, D.C. … there is a crack in her voice, an echo of old childhood hurt when she says, “They sent me back.”

At 15, Ague and two older male friends schemed up a plan to burgle a house because she knew the people and the people weren’t supposed to be home.

Except they were home. Ague says she tried to call it off, but the two boys went ahead. She waited outside, eventually creeping in to see what was taking so long. She saw a man tied up on the floor with telephone cord, a woman was similarly bound in the bathroom, and the two boys were yelling and waving kitchen knives at them.

“They got way crazy. Everything got pretty much way out of hand,” she says.

Because of her age, she wasn’t auto-declined. Instead, Ague spent 214 days in juvenile detention as a discretionary decline hearing to move her into adult court churned through several judges and five public defenders. Ultimately, a judge told her he saw “a kernel” of potential, kept her in juvenile court where she served a “juvenile life” sentence from 15 to 21 on two counts of kidnap and one of robbery.

She’s the rare person who started so young and was in for so long that she knows the JRA system perhaps better than some administrators — the good, the bad and the b.s.

Ague was in so long — five and a half years — that she took all the high school classes the JRA offered and fought the state to let her take college courses — at that point not allowed — that she paid for through prison jobs and church donations.

When she got out, she attended WSU and graduated last winter with a degree in criminal justice.

Politicians and corrections honchos applaud her gumption: She was a recent Governor’s Spirit Award winner, honoring people who have overcome obstacles … but has still encountered obstacles because of her past.

Political Reality

Some local elected officials go on the record about reform.

Spokane County Prosecuting Attorney STEVE TUCKER says a discussion of auto-declination policies is an important one and suggests it would be an excellent topic for the next gathering of the state’s county prosecutors.

“We have a meeting coming up in October and I’m going to have to throw that out” for discussion, Tucker says, and assess the mood of the state’s 39 county prosecutors.

“My understanding is that the prosecutors, as an association, are opposed,” says Senate Majority Leader LISA BROWN(D-Spokane). But, she adds, there are already proposals for reform swirling around Olympia, including restricting the auto-decline age to 17 and eliminating certain crimes, such as burglary, from the auto-decline list.

“I’m interested, and I’m sure some other legislators are interested, in continuing to look at whether we’ve struck the right balance,” Brown says. “As I understand it, the Sentencing Guidelines Commission has recommended that we move in the direction of having fewer auto-declines, which would mean more discretion in whether a juvenile goes to adult court.”

This year’s legislative session will be 105 days instead of 60, Brown says, so there will be more time to consider reform and start the tug-of-war among interest groups.

Sen. CHRIS MARR (D-Spokane) says he is willing to consider legislation to reform automatic declinations.

“Generally, I am not for lenience as it relates to crimes,” he says. “Having said that, I am concerned by evidence that shows, in a number of instances, having kids mainstreamed into a system designed for adults could promote a higher rate of recidivism.”

Reps. JOHN DRISCOLL and TIMM ORMSBY, both

Spokane Democrats, advocate for sending juveniles to the juvenile

justice system, recognizing that kids are different than adults. (Kevin Taylor and Heidi Groover)

Spokane County pulled her from an internship working with kids in juvie last year because, Ague says, “They didn’t want to see the headline, ‘Kidnapper working in detention.’

“They were covering their asses,” she says. “If the goal is to rehabilitate, what is it when you finish successfully — and there are not a lot of success stories — what does it say when you are beating all the odds and they’re still going to throw bricks?”

She is seeking a pardon today, Sept. 9, appearing before the Pardons and Clemency Board in Olympia. (Update here.) Without one, she says, her voice dropping, “I’m pretty much screwed.”

Ague finds it infuriating, cruel even, that kids much like her — from poor families, broken families, uneducated families — are being charged as adults through automatic declinations and coming out with indelible Class A felony records.

It’s like the state is just herding them back towards prison.

“You look at the statistics,” Ague says, “and those are the kids that are all there: the brokest, the poorest, the ones that are the most vulnerable.”

WHAT NOW?

What are the chances for reforming the system and eliminating automatic declinations?

Rep. Mary Lou Dickerson, the Seattle Democrat, says change in the Legislature may take awhile, but there’s been progress.

She helped pass recent reforms that have allowed sealing of juvenile records in some cases and erased the “once an adult, always an adult” policy. Under the “always an adult” rule, an offender who was auto-declined into adult court would be always tried as an adult in any subsequent crimes — even if they were not on the auto-decline list and even if the offender was found innocent of the original charge.

Colgan, of the Columbia Legal Foundation, says legislators not wanting to appear soft on crime may wish to rethink their positions on auto-declines in light of new data. Current policies are creating more — and more violent — criminals, she says. That’s hardly being tough on crime. (See “Political Reality” sidebar.)

“We referenced a study the Centers for Disease Control did that found putting kids in with adults makes them not only more likely to recidivate [re-offend], but recidivate more violently,” Colgan says. “If the intent is to protect the public, is this the way?”

Griffith, the acting director of the JRA program division, says when it comes to abolishing auto-declines, “I would advocate for that. I am not fond of the auto-decline option — I think judges should have [involvement].”

Griffith says he doesn’t see any organized reform effort at this point, but says the Sentencing Guidelines Commission may be taking a look at juvenile sentencing in light of ongoing brain development research.

Rep. Susan Fagan (R-Pullman), personally knows Starcia Ague and is among the people who have cheered her success, even sending graduation presents. Yet she voted against the bill to allow juveniles to eventually be able to seal most felony records.

“If everybody was like her, I would be able to support the legislation, but I don’t think five years is enough time,” Fagan says. “Again, we are talking about paying our debt to society for how we injured society.”

Paying a debt to society is one thing, Ague says, but when society doesn’t help you fix what’s broken and lets you fail again and again … well, that’s something that also needs to be addressed.

“I’ve met so many great people — people like Representative Fagan,” Ague says. “But if you are someone like me — spent your life in an institution, been raised by correctional staff — if you don’t have some kind of a transition [to leave prison], it’s like throwing you to the wolves.

“No one ever … I can’t believe that not one person in the whole system managed to take me out of bad places,” she says. “I filed CHINS petitions on myself to get out of my environment and … I mean … they sent me back to my mom.”

In all the talk about adult punishment for juveniles, she says, no one should ever lose sight of the child.

Comments? Send them totheeditor@inlander.com. Heidi Groover contributed to this report.

The Inlander is committed to exposing miscarriages of justice. Send tips and story ideas to injustice [at] inlander.com or call the news tip line at (509) 325-0634 ext. 264. Read more Injustice Project stories

INJUSTICE PROJECT

Strong Arm of the Law

What happens when someone complains a cop used excessive force? Usually, not much. NICHOLAS DESHAIS

INJUSTICE PROJECT

Reasonable Doubt

How spotty detective work and careless prosecution may have put the wrong man behind bars. JACOB FRIES