At her best, Amanda Cook could still give off the light of her former self — the bright, giggly girl who grew into a doting young mother. A photo from last summer shows Cook posing confidently with a deep-dimpled grin, one leg jutting forward, one shoulder cocked back, a warm reflection of the Spokane woman who once loved shopping and doing her sister's hair.

"She liked music and she liked fashion," her older sister Melissa Parker says. "She had a very good heart. ... If anyone in her family needed anything, she was right there."

At her worst, the 25-year-old Cook turned unpredictable, paranoid and sometimes violent. Parker says "everything went all bad" a few years ago. Her sister fell into drugs, lost her daughter to the state and racked up a string of arrests for increasingly troubling crimes.

While Parker blames the drugs, she says she had noticed lingering effects on Cook's mental state. She would hallucinate, suffer long bouts of crying and fear those around her. In a fit of frustration last March, Cook intentionally set fire to a trailer where she lived near Elk. In early October, she was arrested for assault after smashing through a window into her mother's Spokane home and attacking her with a wooden club.

"She was a good girl before all of that," Parker says. "She liked to draw. She drew butterflies."

With her most recent booking, Cook returned to a jail system overrun by mental health challenges, a system where inmates spend all day locked down, where medication comes slowly and where a simple evaluation can stall proceedings for months, leaving people stranded behind bars regardless of guilt or innocence — a system that ultimately could not save Cook from herself.

From jail, Cook wrote letters about her growing confusion, fear and regret. On Dec. 3, she was released from her cell to take a shower. Somehow, she smuggled out a bedsheet.

"I have hurt everyone who has cared about me. ... I'm really not sure what has gotten into me honestly." — Cook wrote in a letter, Nov. 3

Within the black-mirrored glass monolith of the Spokane County Jail, the regional criminal justice system bears a responsibility it was never built to shoulder. In the wake of deinstitutionalization in the 1970s, local jail facilities have become the modern asylums, granted dwindling resources to meet the growing demands of a nuanced population of inmates with diverse treatment needs and sensitivities.

The county jails in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York now stand as the three largest mental health facilities in the nation, together treating more than two and a half times the combined capacity of the country's top three mental health hospitals.

Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich argues that federal and state lawmakers have forced mental health care onto underfunded local governments. With state and community facilities cutting programs, jails across the country have evolved into warehouses for locking up large numbers of the mentally ill. A 2012 survey of 20,000 jail inmates found 17 percent met the criteria for serious mental illness.

"The criminal justice system," Knezovich says, "is not really the proper place for mental health treatment. ... The jail is [already] way beyond its limits."

In 2009, the Spokane County Jail took the unprecedented step of obtaining certification as a licensed mental health provider, becoming the only jail in the state to do so and making it the second largest mental health facility in Washington. It now provides mental health services for more than 2,000 inmates a year — one in six of the approximately 12,000 adults under age 55 who received mental health services of any kind in Spokane County each year.

Kristina Ray serves as manager of the jail's mental health department. Since joining the jail staff in 2007, Ray says mental health personnel have worked to provide the same level of care as any other treatment facility, even as those types of facilities have closed their doors or cut their numbers of beds. Her staff of three mental health professionals, plus a few contract and intern positions, remains on call 24 hours a day. They assess inmates, provide stabilization, offer short-term counseling and develop discharge plans for follow-up upon release.

"When I first started here, corrections and mental health were two very separate fields," Ray says. "I have seen a complete 180-degree shift."

A 2012 audit of the Spokane County Jail by the Regional Support Network, which oversees mental health services across Eastern Washington, found the staff responsive and well organized. Mental health advocates with the nonprofit Disability Rights Washington and other organizations have commended the Spokane jail for several proactive policies, but they also argue the system and services remain insufficient all while new demands continue to multiply.

Ray says the number of local inmates with mental health issues has gone up slightly, rising from about 1,700 in 2010 to 2,050 in the 2013 contract year. But the severity of conditions also has increased. As other facilities have cut community-based services, she says, the people showing up in the Spokane jail have suffered from more significant problems, more dangerous signs of crisis.

"They're more symptomatic," Ray says. "They've been off their medication longer. They're higher risk. It's a lot more severe cases."

Five years ago, the jail might have had five people on suicide watch.

"Now, it's 20," she says, "and that's not uncommon."

"I'm sorry I lost my mind! I hate what has happened to me." — Nov. 3

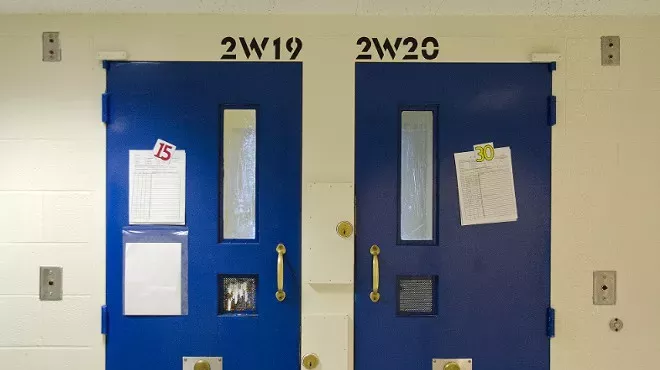

Behind the door to 2W19, one of several suicide watch cells on level Two-West, a 45-year-old man with a salt-and-pepper beard lets out a string of broken wails, seemingly drowning in his own screams. He then goes quiet, pressing himself hard into the far corner of his cell as Cory Standridge, one of the jail's mental health professionals, steps in to check on him.

Each inmate receives a mental health assessment upon booking. People may self-report a previous diagnosis or admit thoughts of self-harm. Police officers can make referrals or corrections staff may flag unusual behavior. Inmates with severe symptoms may require immediate "crisis intervention" to control their outbursts.

"Sometimes when you guys hear me scream, it's to get the raging thoughts out of my head," the man tells Standridge, pausing, "You know what I see right now? Math."

Wrapped in a blanket, the man says he sees nonexistent numbers wallpapering his cell. He had an argument with God, he explains, over the pounds per square inch of force needed to break the skin of an apple. God won, of course. In a strained voice, he starts listing the religious significance of prime numbers. He stops to rub his face.

"Ahh. I just want my meds," he moans. "You guys have been working on it since Monday."

It's now Thursday.

Jail officials say nearly nine out of 10 mental health inmates require some kind of medication stabilization, but the process can be complicated. Standridge tells the man she has to have him sign a release to get his prescription from his doctor, then his doctor has to confirm the medication and dosage, then the jail's physician has to approve the dosage, then the jail has to actually order the medication from the pharmacy, then he can get his meds.

The process can take several days. Inmates cannot bring their own supply for fear it could be tainted or misused. The jail's mental health professionals also can prescribe medications, but inmate accounts suggest that process can still take weeks in some cases.

In the case of Amanda Cook, her sister says the Pend Oreille County Corrections Facility in Newport had Cook on medication last fall that helped moderate her mood, but when she was released and soon rebooked into the Spokane jail in October, she could not get back on those meds. Spokane officials would not comment on Cook's treatment.

"They should have known about the medication she was on," Parker argues. "I don't understand why they weren't communicating [with Pend Oreille County]. I don't understand why Spokane wasn't doing anything to help her."

Many factors determine if and when an inmate receives medication. Spokane jail nurse manager Cheryl Slagle says the jail transitioned from a Pennsylvania-based pharmacy to a local pharmacy in September, which has helped speed up parts of the process. They can now fill emergency prescriptions in less than two hours, but they still have to follow proper safeguards.

Standridge tells the man in the blanket that she will follow up on his medication and see about getting him access to a phone.

"You're never coming back," he growls.

"Look, we all know my mind got f—-ed up!" — Nov. 3

At her desk in the nearby county Public Defender's office, defense attorney Kari Reardon tallies her caseload from last year — 262 separate charges. Of those, 29 charges — more than 11 percent — were dismissed because the defendant was not mentally competent to assist in his or her own defense. She then counts up her 64 open cases, 17 of which have stalled as defendants wait for mental health evaluations.

Reardon, who sits on the mental health advisory board for the Spokane County Regional Support Network, acknowledges her client ratio might be a little higher than average, but there's still a huge number of mentally ill defendants in the local criminal justice system — tying up courts, law enforcement operations and especially the Spokane jail.

"Our folks with jail mental health have a tremendous burden," she says. "I know they try. It's just an overwhelming amount of people."

Reardon, like many other advocates, argues the criminal justice system should not be expected to provide primary housing and treatment for those who need mental health services. Jails were never really meant to be mental care facilities. But for many, they have become the only option.

In July, one of Reardon's clients allegedly started throwing rocks at cars outside Spokane Falls Community College. Court records indicate that when campus security confronted him, the 32-year-old man admitted the offense, saying "he wanted to go to jail to receive medication."

"That gentleman needed mental health help and was literally damaging cars so he could go to the jail and get his medication," Reardon says. "That a person commits a crime to get help is a really sad state of affairs."

Jail officials confirm similar stories from other inmates. One 46-year-old Spokane woman recently booked into the jail has a long history of committing petty crimes to receive a monthly injection. During an interview outside her cell, the woman tells the Inlander she had few options for treatment at the time. She was homeless. She didn't have insurance. So every other month she would go to the emergency room, and the next month she would get herself arrested on a minor crime.

"It's just tough," the woman says.

For those with few options, mental health manager Ray says the jail can serve an important role in stabilizing individuals and connecting them to long-term community care providers. Navigating any medical or mental health system can be difficult, even for those without mental issues, so the jail at least provides an accessible route to those who need it. Ray acknowledges it's not ideal, but says other services can have long wait lists, high costs or confusing restrictions — the jail has to admit and treat everyone immediately.

"We'll see them at any time for any reason," Ray says. "They don't get billed. There's no charge to receive mental health care. ... They don't have those barriers to getting treatment here."

"You guys want your sister back and I want to be a part of my family again. I've got a lot of shameful guilt I just need to let go of, but it's hard. Honestly, I feel like a freak show. I'm really hoping to still have a chance to get my mind right and be able to be with you where I belong." — Nov. 18

Dark pink doors seal the segregated cells along the double-tiered block of Four-East where most of the jail's male offenders with acute mental health issues wait out their time. Each door has a small slot about three feet off the floor. Eyes peek out from many of the openings as men in yellow jumpsuits crouch down to stare or shout through their only hatch to the outside world. An arm emerges from one slot, clutching an envelope, passing it to a neighboring door where another hand snatches up the letter.

Four-East has 46 single-person cells, almost always full. Due to staff shortages and security protocols, mental health inmates remain locked down in their cells for 23 hours a day, sometimes more. During their one hour of "out time," they can wander the carpeted common area, pick out books, shower or watch the flat-screen TV on the wall. Jail officials say they dislike the heavy restrictions, but have limited resources.

In cell 4E31, 28-year-old Scott Adams perches on the edge of his bunk. He wears two jumpsuits, doubling layers for warmth. The Army veteran has rough-cut brown hair and the word "GRUNT" tattooed in black capital letters down the length of his forearm. He seems tired, but agreeable, as he leans forward with a sort of resignation regarding the concrete all around him.

"I've started to name the walls," Adams says, pointing. "That one's Kennedy. The door is Logan."

His cell has high ceilings and a small vertical window. By the door, a stainless steel combination sink-toilet fixture bolts into the corner. You can talk to other inmates through the sink if you blow all the water out of the pipes, Adams explains, but the toilet plumbing also is connected, so whatever gets flushed upstairs ends up in his toilet bowl until he flushes it down the line. He looks up to the ceiling as a loud clanging starts up from the cell above him.

"It's a horrible atmosphere," he says, adding, "No [other jail] has a setup like this where they just lock you in your room all day. ... I think this is extremely counterproductive."

Many of Washington's jails do, though. While jail officials say mentally ill inmates have trouble "maintaining" if they are not housed by themselves, civil rights advocates argue constant lockdown forces inmates into de facto solitary confinement, which is typically used as extreme punishment. Research studies going back to the 1970s associate solitary confinement with increased depression, hypersensitivity, fear, hallucination and incidents of self-mutilation.

Reardon notes that Death Row inmates in Walla Walla get more time out of their cells than local mental health inmates at the county jail.

"If you were already sane, that would probably drive you insane," she says of the isolation and disruptive environment.

Adams says he appreciates the Spokane mental health staff, but says the jail conditions come close to "torture." He can't sleep. He suffers constant nightmares. His fellow inmates will scream and holler as they struggle with their own demons next door. And the inmate above him continues banging away at all hours. Adams sometimes uses toilet paper to plug his ears against the racket. He takes anti-anxiety medication to calm his nerves.

"There's nowhere to go," he says. "You just lay here and take it."

"I talked to my attorney today. She says Eastern is gonna come and give me an evaluation here in the next week or so. I'll let you know. Please pray for me. ... I need to pull myself together. I'm losing my mind." — Nov. 18

Any defendants with suspected mental health issues must undergo a psychological evaluation to determine whether they are competent to stand trial or whether they can assist in their own defense. Once a question of competency is raised, nothing can move forward until a state-licensed evaluator can meet with and question the defendant for about an hour. Eastern State Hospital provides seven evaluators to cover 20 counties across the east side of the state.

"There's a severe bottleneck on that," Sheriff Knezovich says. "We really need to get that system fixed."

Ray, the jail mental health manager, says Eastern State has a lengthy waiting list. Inmates can face weeks or months of sitting in jail just for an evaluation, before they can even begin any trial proceedings. Mental health inmates can sometimes serve more time in jail awaiting an evaluation than they would have if convicted of their underlying charge. It's a major frustration for all involved.

In May of 2012, the Washington State Legislature imposed new standards requiring state hospitals to conduct evaluations within seven days if a defendant was in custody of the jail. A new legislative audit report released Jan. 7 shows Eastern State Hospital met that deadline in only 1 percent of hundreds of evaluations it conducted. The average waiting period stretched to 33 days.

Monthly

Public defender Reardon says she sent Eastern State an urgent letter on Dec. 2 over a client she considered "extremely, extremely depressed," asking for help to arrange a faster evaluation. She sent a follow-up letter on Dec. 28, reinforcing her plea. The best she could get was Feb. 5, more than two months after his initial booking.

"I've had a case recently where I finally just brought a motion to hold Eastern in contempt," she says. "That got my client evaluated more quickly, which is an unfortunate reality."

Amanda Cook was booked into the Spokane County Jail on Oct. 12. Her attorney filed a motion seeking a mental health evaluation on Oct. 28. Seven days went by. Then 33 days passed without any evaluation. Cook sat waiting, locked down alongside dozens of other inmates facing similar challenges. Her letters turned despondent.

"I don't know what the heck happened," Cook wrote her sister on Thanksgiving. "My head really got twisted, Melissa. Why did things happen like this? I think I see where everything is going."

Parker says Cook needed medication and inpatient treatment as she grew increasingly afraid of the jail staff and depressed over the lost custody of her young daughter. On Dec. 3, just days after her daughter's 6th birthday and with the holidays quickly approaching, Cook came to her breaking point.

"I really don't understand why Spokane didn't have her on suicide watch," Parker says. "They kept putting [her evaluation] off and putting it off, until finally she couldn't take it anymore."

Cook crept into the showers at about 11:40 am and threw her bedsheet up over part of a vent, investigators say. Jail staff found her hanging, alone and unconscious, about 30 minutes later. She never woke up and on Dec. 6 was declared dead.

"I didn't mean to cause so many problems ... I wish I would have gotten my head together ... Then none of this would have happened." — Nov. 28

Parker says her family wants answers. Despite Cook's previous letters, investigators did not recover any note. Detectives found no sign of any criminal involvement and family members do not dispute the death was suicide. But what Parker wants to know is what else should have been done? What could be done in the future so other people don't suffer the same fate?

"It could have been prevented," Parker says. "Eventually, with proper treatment, she could have been helped."

Ray could not comment on Cook's death, but says her staff works tirelessly to provide the best possible care to everyone in the jail. She knows they could do better with more staffing or money. A new jail with advanced treatment facilities would go a long way. Her staff also could use a full-time position to follow up with inmates after release to make sure they attend appointments. County officials also could direct more defendants into specialized Mental Health and Drug courts.

Eastern State Hospital has requested funding for more beds and evaluators to expand treatment and speed evaluations. Disability Rights Washington recommends increased involvement with families and reducing the amount of time offenders spend in isolation. They say some jails have introduced policies to refuse inmates with severe conditions, directing them to a facility of higher care.

"There's so much more that everybody could do," Ray says. "We could offer more services here if we had more resources and more staffing. Everybody could offer a higher level of care so [people] don't get stuck in the system, so they don't kind of go from the jail to Eastern to the streets and back and forth. But that all boils down to funding."

As Reardon again counts through her many clients with mental health issues, she says she reminds herself each defendant is somebody's sister or father or grandparent. They're all people who deserve the same compassion as anyone. But instead of getting treatment through a hospital, they are getting trapped in a legal system that is failing them.

"Our system is broken," she says. "It's nothing any one person in particular is doing wrong, but our system is broken." ♦

Editor’s note: These special reports are the first in our “State of Mind” series delving into the issue of mental health. Besides exposing serious problems, we will also strive to tell success stories and examine potential solutions. If you have feedback or a story to share, please email us at editor@inlander.com.