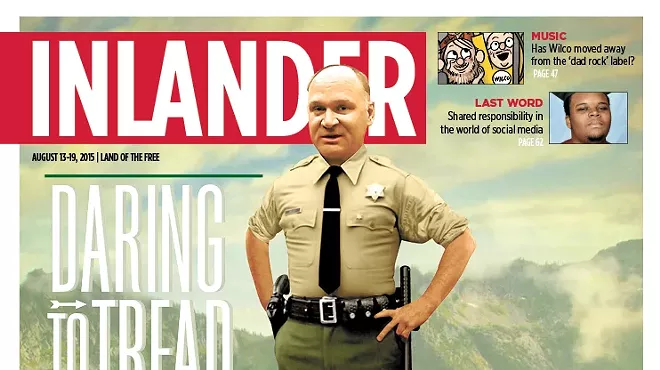

Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich paces on a stage at Central Valley High School. He's stone-faced and sober-toned, a gun in his holster, a sheriff's star on his chest. He reminds the crowd that had a certain bomb gone off, he might be dead.

Kevin Harpham, a Stevens County man drawn to 9/11 conspiracy theories and white supremacist message boards, built a directional bomb. He filled it with lead weights and, in a particular nasty twist, seasoned it with rat poison — an anticoagulant intended to stop bloody wounds from clotting. If it hadn't been for three temp workers reporting a suspicious backpack on a park bench in downtown Spokane, the device could have blown up hundreds at 2011's Martin Luther King Jr. parade.

"If it would have went off, I might not be here tonight. I was in this parade," Knezovich tells the crowd gathered at Central Valley in late June. He pauses, letting it sink in. "With 500 or so kids. Children."

Knezovich will go on to talk about how Islamic extremism, including ISIS, is a threat. But he spends much more time in his presentation discussing another type of terrorism. He clicks through slide after slide showing the Inland Northwest's own history of anti-government, right-wing violence.

He cites examples like The Order, the white supremacist group out of Metaline Falls, Washington, responsible in the '80s for counterfeiting, robbing banks, attacking armored cars and murdering a Jewish talk show host. The Colville-based Kehoe brothers, who blew up a pipe bomb outside of Spokane City Hall in 1996. The anti-government racists who bombed a Spokesman-Review office, a US Bank branch and a Planned Parenthood clinic that same year. The man who used a Glock sold at a Spokane gun show to kill a letter carrier, after shooting up a Los Angeles Jewish community center in 1999. The Idaho survivalist militia leader who built homemade bombs and explosive booby traps and was arrested for planning to kill a federal judge in 2002. The Spokane resident who firebombed a synagogue in Oklahoma City in 2004. And Harpham's thwarted bomb in 2011.

Knezovich isn't giving his talk, titled "The Threats We Face," simply to highlight extremism or justify the department's use of heavy-duty, military-grade equipment. His criticism goes further.

"The thing is — some of you are tacitly supporting their ideologies," Knezovich tells the audience of nearly 350.

Knezovich is one of the region's most popular Republicans. Since 2006, he's won three elections with at least 70 percent of the vote. But now, on theater stages, in interviews, in emails and private Facebook messages, Knezovich is waging a campaign against a section of his own party. He's hanging moral culpability for future violent acts on the shoulders of local Tea Party leaders, libertarians and, in particular, Washington state Rep. Matt Shea.

Knezovich blames Shea and his ilk for spreading fear, perpetuating outlandish conspiracy theories and bashing law enforcement. He blames them, partly, for the swarm of death threats that have recently rained down upon himself and one of his deputies.

"If anything happens to my deputies, I hope you all hold them accountable," Knezovich tells the crowd.

"You have a sector that is preaching hate and falsehood, then you have a responsibility to shut that down," Knezovich says in an interview with the Inlander. "Matt Shea has a responsibility to shut that down. He feeds the fire."

Knezovich's targets fire back, however, accusing the sheriff of being a bully driven by his own paranoia and fear, of dangerously lumping their groups in with the worst kind of domestic terrorists. Indeed, while the sheriff is inside giving his talk, protesters are outside declaring that it's Knezovich everyone should be worried about.

Scott Maclay, of the Rattlesnake Motorcycle Club, had summoned demonstrators to protest the sheriff's speech in a Craigslist post titled "The manufactured enemies of Ozzie Knezovich." It called Knezovich a "Terrorist Sheriff" and accused him of covering up deputy misdeeds and "Mormonizing" the Sheriff's Office.

At its most basic, the conflict puts two competing impulses: On one side, fear of government. On the other, fear of extremists.

"Fear is a big part of this," says University of Hartford militia movement scholar Robert Churchill. "But it all strikes me, when things get really dangerous is when the federal government gets afraid of these groups and the groups get afraid of the federal government. And the groups begin to dance with each other."

'A LOT OF CONSTITUTIONALISTS'

The Holiday and Heroes event last December at Walmart was supposed to be all about the Spokane County Sheriff's Office helping kids. It resulted in death threats.

These events have been taking place in Spokane County for more than a decade. Each time, sheriff's deputies pick up kids from more than 30 underprivileged families, bring them to the Spokane Valley Walmart and shop with them for presents for their siblings and parents. They go home with gifts — bicycles, dolls, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle action figures — and a big box of food.

The children also get a chance to meet law enforcement and check out their cool equipment. One photo from the event shows a kid smiling and sitting in an MRAP — the hulking black armored Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected assault vehicle meant to withstand armor-piercing bombs.

This was back in December, just a few months after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and subsequent protests had thrust the issue of "police militarization" into the mainstream. Video streams, tweets and live telecasts let Americans see it all happen in real time: cops in riot helmets, Kevlar body armor, gas masks, camouflage pants with pouches for extra ammo magazines, and sheaths with KA-BAR-style knives. The imagery of heavily armed officers sparked national debate, Senate hearings and an executive order from President Obama to review the sort of equipment that local police forces are getting from the military.

In his presentation, Knezovich calls "police militarization" a myth. When bad guys wield heavy weapons, he argues, the good guys need heavy armor and heavy weapons to respond. He points to the riots in Baltimore: Here's what happens when police don't use their heavy-duty equipment when they should — the National Guard, a true military force, has to come in.

John Charleston and Cecily Wright, Washington state coordinators for the Tea Party Patriots, say a woman contacted them through the Tea Party Facebook page with a cellphone video she had taken at the Holidays and Heroes event.

"She was adamant she wanted to be anonymous," Charleston says. "She has a fear of law enforcement."

The woman worries the MRAP is a ploy to desensitize the kids to military equipment, to make them want to grow up and be a part of a militarized police force. On video, she asks deputies whether vehicles like the MRAP would be turned on innocent citizens.

"Constitutionally, they can't," a sheriff's deputy begins to answer. But the woman interrupts him, saying that Obama is stepping all over the Constitution. As the conversation progresses, the deputies repeatedly explain that the MRAP is crucial to protect them from heavy weapons fire.

But then Deputy Jerry Moffett utters the fateful phrase, a quick sound bite that turned into months of outrage fodder for protesters and politicians like Shea: "I mean, we've got a lot of constitutionalists and a lot of people that stockpile weapons," Moffett says on camera. "A lot of ammunition."

It was, says Amy Cooter, a Vanderbilt University lecturer who studies the militia movement, "maybe the worst thing you could possibly say. ... I don't think there's any coming back from what was said. They will never trust you, no matter how much time passes."

The video of the deputy's comment went viral, sparking protests, anger and articles on right-wing websites like The Blaze and Infowars.

Knezovich pushed back, noting the deputy's military service and awards. He said he regretted that the deputy chose his "words poorly" and used broad brushstrokes. He argued that the clip had been taken out of context. It did little to dam the oncoming flood.

"Do you realize how many death threats the kid got?" Knezovich says.

"I hope your MRAP and your SWAT team takes you down," a voicemail message to the Sheriff's Office said. "Sheriff Ozzie, just crawl up in a corner and die."

The comments about the video on Infowars and on YouTube included statements like: "Cops who think that should be shot on the spot," and "This sheriff is already dead, and he doesn't even know it yet. How sad."

Other commenters wished for death by fire or heart attack, or for him to be hanged for treason. "How about, ambush him and black-van his ass, and show him what happens when Pats catch communists," one YouTube comment reads. "We will put an end to you in a harsh manner."

A few laid out, in terrifying detail, how they would kill officers in an MRAP with various weapons or improvised bombs. Several wanted to "light the bitch on fire."

"With the stormtroopers inside," one InfoWars commenter fantasized. "Listen to the screams, music to my ears, the terrorist frying."

Knezovich says he takes these threats seriously, but that the Sheriff's Office has not actively investigated any of them. Tracking down anonymous Internet comments isn't easy. Still, the sheriff has used those threats, both privately and publicly, to condemn those who have attacked his deputy's comment. A few days before his presentation, Knezovich sent a Facebook message to Charleston and Wright, blaming them for uploading a copy of the video, and citing a threatening message he'd recently received.

"This is what your hate is doing, John," Knezovich wrote. "I hope this community holds you responsible for spreading this fear if one of our deputies gets hurt."

Wright and Charleston note that their copy of the MRAP interview actually went up after Infowars' post, and that months had passed before Knezovich told them the video had led to death threats.

"I did not know that that particular video is apparently just a raw nerve with Knezovich," Wright says. "If he had ever communicated with us, we could certainly have worked on that situation." (Knezovich says he contacted them as soon after he learned of their involvement with the video.)

Though Knezovich has made it a mission to counter the "garbage" of Charleston and Wright, they say they don't want a war with the sheriff. Still, they question where the deputy heard the word "Constitutionalist" in a way that applied to violent groups, and bristle at feeling lumped in with the racists in Knezovich's presentation.

"Those are the sovereign citizens. Those are white supremacists. Those are Nazis. Those are nutjobs," Wright says. "The line has totally been blurred."

GOD AND COUNTRY

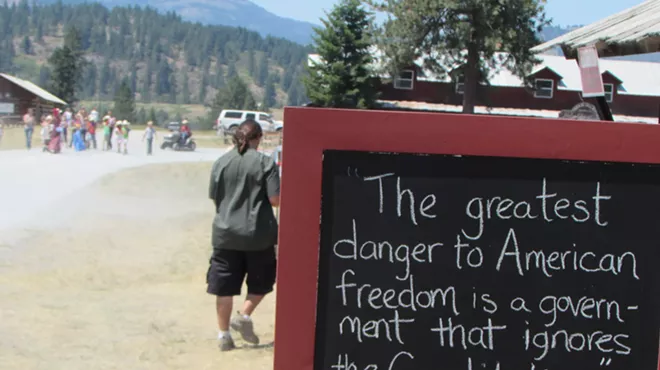

It's the Fourth of July, and Matt Shea, once again, is on stage at the Marble Country's 21st Annual God and Country Celebration at the very tip of Stevens County, a gigantic American flag to his back and the words "Marble Country: Building our Children's Inheritance" painted on rolling hills above him.

A chalkboard at the entrance of Marble Country proclaims: "'The greatest danger to American freedom is a government that ignores the Constitution' — Thomas Jefferson." Jefferson never said that — its first known use was apparently online in December of 2004 — but here the sentiment stands. Love of the Constitution, love of country, love of freedom, love of religion — it's everywhere here, and so are warnings about a government infringing upon every one of these.

But I'm not allowed in.

I've pre-registered for the event, drove two hours and paid the $20 fee. But when they find out I'm with the Inlander, the woman at the registration booth radios Shea and another leader to see if I can stay. I can't. Kindly, but firmly, the group returns my $20 and tells me I need to leave. I'm media. Anyone once associated with the Upper Columbia Human Rights Coalition also has been banned.

Shea's relationship with the local media — which reported on his messy divorce and the time he flashed an unlicensed gun at a motorist — has long been strained. Asked for a one-on-one interview for this story, Shea declined, complaining that his words had been twisted in the past.

Shea, an Iraq veteran, speaks with the structure and fervor of a fiery preacher, his volume rising, calling for those here to be like the German Christians who opposed Adolf Hitler, and fight "intentional, deliberate evil," according to audio of his speech.

He says government is illegally seizing private property, trying to control every facet of their lives, creating a financial crisis, indoctrinating their children, demonizing Christians and ignoring state sovereignty. But do not be afraid. God is in control, he says, so patriots should be posting lists of grievances on government doors throughout the country.

"We should tell them enough is enough! The people have had enough! We're not going to take it anymore!" Shea yells. "And if you don't change, we the people — the government of this country — will change it for you!"

And the crowd goes wild.

"He's found his echo chamber, and he's a hero there," Knezovich says.

At this event, you can find all the connection and contradiction between patriotism, religion and racism that the sheriff fears.

Marble Community Fellowship's founder and leader, Barry Byrd, helped pen a 1988 manifesto called the Remnant Resolves. The document included passages stating that it's blasphemous to call "antichrists" like Jews "the Chosen People" or to allow them to hold public office. It says that "Inter-racial marriage pollutes the integrity of marriage."

Since then, the Byrds have fervently condemned racism and distanced themselves from their former controversial church, The Ark in Colville. Marble Community Fellowship counts an African-American, Doug Taft, among its leadership. (More than once, Shea has pointed to his close friendship with Taft to counter accusations of racism.)

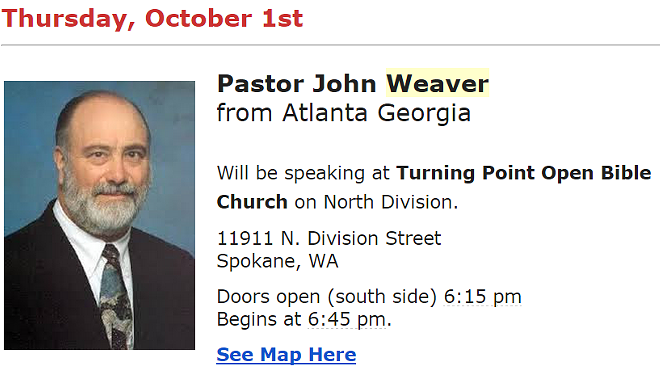

Yet Marble's break with racist ideology hasn't been a clean one. Along with Shea, one of the key speakers at this year's God and Country rally was Pastor John Weaver, who has a history: He's praised the Confederacy in sermon after sermon. He's put out a tract arguing that slavery is not inherently against Scripture and that some slaves "blessed the Lord" for saving them from Africa with their enslavement. He has called interracial marriage "a form of adultery."

"If God had desired that we intermarry and amalgamate and become one, why would he have begun the other races to begin with?" Weaver asked in one sermon in his gentle drawl.

Drawing upon years of Council of Conservative Citizens' newsletters, the hate-watch nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center says Weaver was a "leading member" of the group. Before murdering nine black people at a Charleston, South Carolina, church prayer meeting in June, Dylann Roof wrote a manifesto about coming across "pages upon pages of these brutal black on white murders" on the Council of Conservative Citizens website after Trayvon Martin's controversial death, sending him down a racist rabbit hole.

It's exactly this type of situation that activists like Mark Potok, senior fellow of the Southern Poverty Law Center, worry about these days. Violence isn't as likely to come from groups like the Order or the Aryan Nation, as much as from isolated loners like Roof or Harpham becoming radicalized from related blogs and message boards. "The real danger comes from lone wolves," Potok says.

That's why former state Sen. John Smith gets worried. He's warned Knezovich specifically of his concerns about the violent rhetoric he's heard up in Stevens County.

After all, growing up in the milieu of hatred and white supremacy, he saw firsthand how words can grow violent ideas into violent actions.

He remembers seeing his grandfather in Boise, after a house fire and losing his job managing a bowling alley, find solace in all the wrong ideas and all the wrong people.

"These other people came into his life and hijacked his life," Smith says. They gave him people to blame — told him he lost his job because, say, the Jews had it out for him. His grandfather turned into a bitter, angry person — and took it out on those around him.

Smith was about the age of 14, he remembers, walking down from his bedroom while at his grandfather's house. There, at the breakfast table covered with maps and booklets, with his grandfather and a half-dozen others, was Aryan Nations founder Richard Butler, sweaty, overweight, scowling. As Smith made a sandwich, he listened to them spit slurs and profanity about all those who were to blame for the problems of the world while they dreamed up violent fantasies of revolution. Occasionally, they'd quote Scripture.

"As if this was some sort of righteous holy thing," Smith says. "It literally turned my stomach."

These days, Smith thinks a lot about the actual violence and bombs inspired by Butler and the Order. Violence like that of David Tate, arrested in 1985 for killing a Missouri state trooper at a traffic stop.

"I think that David Tate's dad was one of the guys at the table," Smith says. Even now, he worries about talking about this kind of stuff, that it paints a bull's-eye on his back and his family's.

But he believes he needs to talk about it. Because when he remembers hearing someone say something like, "If all of you knew half of what goes on in Olympia, you'd all blow the place up" at a Marble God and Country rally two years ago, he doesn't dismiss it as harmless hyperbole.

He's seen "what 'harmless hyperbole' can lead people to do."

CONSPIRACY THEORIES

Alex Jones is the force behind Infowars, the Austin, Texas-based right-wing website that was among the first to seize upon the Spokane County deputy's MRAP comments.

In the conspiracy corkboard of Jones' mind, hidden strings are everywhere, connecting everything, pulling the world inexorably toward further domination by the New World Order. Sept. 11 and the Sandy Hook shootings — even tornadoes — are likely government plots. So he screams, he yells until his face turns red, he mocks those who disagree.

"Thaaaat Alex Jones and that Infowars," Jones says in one broadcast, adopting a quavering bumpkin accent to try to imitate Knezovich. "All we're doing is gettin' MRAPs and preparin' to fight the Constitution, and they don't like it!"

Shea rarely grants interviews to local reporters, but happily talks to Infowars.

"I think that anytime we have somebody that is saying innocent citizens — that have done nothing else other than love the Constitution — are somehow the enemy, we don't live in a free country anymore," Shea told Infowars in December. "When that is allowed to stand, then tyranny gets a foothold."

Knezovich, for his part, has long been fighting, maybe in vain, against local conspiracy theories. He's says he's lost who-knows-how-many Saturday mornings spent at his computer — to his wife's frustration — arguing with conspiracy theorists fretting about, say, whether FEMA camps would be used as concentration camps.

He doesn't see Jones as deluded as much as he considers him a charlatan, a scam artist getting rich by hocking snake oil. (The Infowars website sells everything from fluoride-filtration systems to pills to remove radioactivity from water.)

"Alex Jones makes a ton of money selling fear," Knezovich says. "Matt Shea is an elected official who gets elected selling fear."

Jesse Walker, author of United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory, says conspiracy theories have always been common in the U.S., on both sides of the political spectrum. In 2003, he notes, 70 percent of Americans believed that JFK's assassination was a conspiracy and in 2006, one poll showed that more than a third of the country believed it was very or somewhat likely that the United States government had carried out or intentionally allowed the 9/11 attacks. Heck, last week's Republican frontrunner, Donald Trump, famously pushed elaborate conspiracies about Barack Obama's birth certificate.

Knezovich tries to correct the facts. No, the police or military isn't going to come and take away your guns, Knezovich says. No, five Walmarts did not shut down to give the government space to shuffle around military equipment. No, an exasperated Knezovich says, this summer's "Jade Helm" — an eight-week Pentagon training exercise in asymmetric warfare across multiple states — isn't a cover for a military takeover.

In a conversation in his office last Friday, Knezovich holds up his smartphone, and brings up a Washington Post story: "How federal agents foiled a murderous Jade Helm 15 retaliation plot." In response to fears over Jade Helm, the feds allege, three North Carolina men allegedly plotted to draw U.S. forces onto a property full of booby traps in order to kill them.

"This right here is all because of a bunch of words from Alex Jones," Knezovich says. "Alex Jones started the Jade Helm fire. Words become reality."

Lately, Knezovich has been fighting conspiracy theories about himself. At the July 9 meeting of the Spokane County Constitutional Republicans, several attendees, upon spotting two Spokane Valley police vehicles outside the window, began fretting that the deputies were surveilling them. Knezovich was offended by even the suggestion of it.

"To claim that the deputies were there for 45 minutes and that they were taking photos of vehicle license plates and the occupants of the room rises to a level of paranoia that should be shocking but sadly isn't," Knezovich responded by email.

Knezovich hasn't always called out far-right constituents. Like other local Republicans, he's tended to make nice with various conservatives and went so far as to endorse Shea in 2008 and 2010. ("Biggest mistake I ever made," Knezovich says.)

To some, the sheriff's fallout with Shea can be traced to August of 2010, when Deputy Brian Hirzel, while investigating a prowling report in an unmarked car, shot and killed 74-year-old pastor Wayne Scott Creach.

"I think the animosity comes from Shea asking Knezovich to do the right thing, and Knezovich's continual refusal to do what's right," says the pastor's son, Alan Creach.

Creach praises Shea for listening to his concerns, and for introducing a bill restricting the use of unmarked vehicles. Knezovich, however, felt ambushed by Shea's bill.

To Knezovich, the feud with Shea started a year later, when Knezovich invited the Southern Poverty Law Center to train his deputies in response to the foiled Kevin Harpham bomb. A few months earlier, the SPLC had listed Shea as one of the group's "Dirty Dozen" legislators, noting paranoid comments he made about FEMA on the Alex Jones show. Shea castigated Knezovich for inviting them, while Knezovich blamed Shea for not warning him that Shea was on SPLC's list.

It got so bad that before the 2012 election, Spokane County Republican Chairman Matthew Pederson called a diplomatic summit. And so, at a food court table near Yakisoba Noodles in the Spokane Valley Mall, they all met for nearly an hour — hashing out their frustrations. "They were both really trying to put all those things behind them," Pederson says.

The détente didn't last. At the MRAP protest last December, Shea slammed Knezovich: "I'm going to submit today, that the Southern Poverty Law Center — and the sheriff that backs them — is the most dangerous organization in this country."

Knezovich repeatedly calls Shea a liar. Shea suggests the sheriff lacks integrity.

"I'm more than happy to debate him anytime," Knezovich says. "And I'll stand in front of him anytime and answer his questions about integrity."

STANDOFFS

The Inland Northwest has a special role in the origin story of the modern anti-government movement. Twenty-three years ago, a standoff with the feds at a place called Ruby Ridge at the tip of North Idaho forever changed the way that many right-wing groups view the government.

Randy Weaver (no relation to John Weaver) was not a violent man, says Jess Walter, local author of Ruby Ridge. Weaver was a racist, isolationist, paranoid, apocalyptic Christian up in the Idaho mountains, but not violent. But after Weaver sold a sawed-off shotgun to an ATF informant, the ATF tried to turn Weaver into another informant. It turned into a disaster.

On the one side, Walter says today, there were the Weavers, "driven by a paranoid fear of the end of the world." On the law enforcement side, you had an "almost institutional fear of groups like The Order. These groups were bombing people and committing murder and robbing banks... You had these two fears coming down and crashing together."

Ultimately, it ended in a firefight, an 11-day standoff, and the deaths of a federal marshal, Weaver's dog, wife and 14-year-old son.

From then on, the showdown at Ruby Ridge, and the disastrous 1993 siege of a Waco, Texas, Branch Davidian compound, became a rallying cry for some right-wing groups and a catalyst for the rise of the militia movement.

"It both feeds a sense of paranoia and anti-government feeling, but it also proves those feelings. For every group that says your government is out to frame you and kill you, they can point to Ruby Ridge," Walter says. "The worst thing you can do if you have people who have a paranoid fear is to prove it."

The memory of Ruby Ridge was one reason that Shea, the Byrd family and hundreds of others flooded Nevada in April 2014 to support rancher Cliven Bundy as the Bureau of Land Management attempted to round up his cattle due to unpaid grazing fees. Bundy supporters pointed guns at federal officers and federal officers pointed their guns at Bundy supporters.

"We won and those tyrants tucked tail and they ran!" Shea yelled at a gathering in Idaho upon returning from the ranch. "And that's the way it's supposed to be in America! They're supposed to be afraid of us and not the other way around!"

Knezovich, for his part, was disgusted with Shea. "There are people out there looking for that trigger," Knezovich says. "They were praying that trigger would be at Bundy Ranch."

On Facebook, Kit Lange, an Everett-based writer for the Patrick Henry Society website, says she'd been studying up on Ruby Ridge. And she finds frightening parallels with the case of Anthony Bosworth, who'd walked onto the steps of Spokane's federal courthouse this February armed with an AK-47 rifle and a 9mm pistol. When he refused to leave, a federal marshal arrested him for failing to comply.

If it came down to a serious confrontation, Lange promised to be by Bosworth's side.

"We pledge this with our blood and our lives," Lange wrote on Facebook. "If the Federal government attempts to create Ruby Ridge and Waco, they will find themselves up against people who are incredibly well-trained, and incredibly armed."

She wanted to be clear, however, that she wasn't going to start any violence.

"We will not fire the first shot, we will not target innocents. But we will not allow the constant erosion of our rights," she writes. "We will not start this violent phase of this Civil War. But by God, if they bring it, we sure will finish it."

When Lange condemns "first strikes," she means it. She's willing to turn in more reckless members to the cops to stop one.

In 2011, the local GOP nominated Iraq War veteran Roy Murry as one possible replacement for the late state Sen. Bob McCaslin.

But this January, Murry was the name Lange brought to the Washington State Patrol. "He's obviously interested in starting something and we want no part of it," she wrote in an email to WSP, requesting that he be barred from attending their February gun-rights protest in Olympia. "I don't want ANYONE thinking this guy is connected to us in any way."

Lange attached a series of a screenshots of Facebook chats with someone she believes is Murry — a "Roy H. Murray" — who gleefully suggests bringing Black Bloc anarchists and motorcycle gangs to stir up chaos.

"The entire argument of 'never shoot first' is flawed," he wrote to Lange. "Gotta stop thinking Lexington and start thinking [Grand Theft Auto V]." Lange also says she believed that Murry posed a threat to Shea.

Four months later, Murry was arrested on charges of murdering his mother-in-law, father-in-law and brother-in-law, and setting their Colbert, Washington, house on fire.

Such self-policing is not unusual, Cooter, the militia researcher, says. When the feds raided the Hutaree militia in Michigan in 2010, the local constitutionalist militia members tipped the government off to the danger they allegedly posed.

"In some cases, I recommend that local law enforcement treat them like allies," Cooter says. "A vast majority of militia members are law-abiding. They care a lot about the country and the laws, and the last thing they want to do is to hurt people."

DARKEST TIMELINES

Last Wednesday, Shea is in Priest River, Idaho, chanting, "This vet is not a threat! This vet is not a threat!"

A Vietnam veteran had received a letter indicating that, because the Department of Veterans Affairs had determined he wasn't capable of handling his own finances, he would lose his right to purchase or possess firearms.

"People said this would never happen in America. Never," Shea said. "Yet we have this veteran who may have their firearms confiscated from the federal government."

Nobody came to take the veteran's gun. An NRA media liaison tells the Inlander he doesn't know of any examples where guns have actually been seized because of this provision.

But the underlying premise — that this is just the beginning of the government's gun roundup — is central to the dark future laid out by Shea in speech after speech.

At a July meeting of the Spokane County Constitutional Republicans, Shea speaks from a PowerPoint packed with charts, diving into granular detail about economic indicators like the "Baltic Dry Index" and the "velocity of money."

This time, delivering his "The Real Threat We Face: Hint it is Not Constitutionalists" lecture, Shea is more professor than preacher, relatively calm as he warns of governmental tyranny and predicts economic collapse.

In such an event, he and his allies are prepared. They've stocked up enough food and water to share — and he and his fellow constitutionalists have plenty of weapons and ammunition stored to defend their neighbors from looters in the crisis — an extension of love, he says.

"Don't let the people out there say, 'Oh, 5,000 rounds is too much ammunition!'" Shea says.

Shea lumps Knezovich in with "willfully ignorant Loyalists," and slams him for his handling of the Creach shooting. He says he still spots the SPLC's influence in Knezovich's ideology.

"One of the little techniques that's used in the media is they'll say, 'Oh, these are Constitutionalists.' Then in the next breath they'll say, 'These are white supremacists in northeast Washington,'" Shea says. "It's a technique that was actually used by the KGB."

Knezovich sees a dark future too, one where lies, rhetoric and fear divide us, pulling us away from what made our country great. Law enforcement and the government is so disrespected and feared that no one wants to sign up for either. "You will not have a next generation to defend this country," Knezovich says on the stage at Central Valley. "You will have all taught them to hate and distrust this nation."

And then, he says, you'll have more Charleston-type shootings.

"There are some of those folks that want to overthrow the government, period. They want to hit a reset button," Knezovich says. "If they're willing to lie to get that reset button — this is how ISIS starts." ♦

For more information about how different people use the word "constitutionalist" and how it got its controversial modern meaning, click here.

For an expert's take on how to spot a bogus Thomas Jefferson quote, click here.

Rep. Matt Shea and InfoWars reacted to the Spokane sheriff's comments in somewhat predictable ways; read about it here.

Read about how the cover of the issue was put together right here.

The story has been updated since publication.