Driving into Oakesdale, Wash., is like going back in time and finding no one there. Cottonwood seeds float through the air, past the empty library and the abandoned restaurant. The streets are quiet, with only a few cars parked in front of houses plucked from a Norman Rockwell painting.

An Oakesdale native, Mayor Dennis Palmer has seen the town lose businesses, people and its own pride.

“So many people come to me and say, ‘Denny, what kind of businesses can we get in Oakesdale?” he says. “We’ve had them all here and they’ve all gone. So much has changed over the years.”

When he graduated from Oakesdale’s only school in 1960, there were 21 students in his class and six places in town to buy gasoline. Today, there’s one gas station, and the school’s most recent graduating class had eight students.

Palmer remembers the once-bustling machinery shops, tractor dealerships and flour mills. He points to the town’s only restaurant, now closed. It’s empty inside, just shadows where tables and chairs once sat.

Over the past 10 years, Oakesdale has grown by exactly two people while the surrounding area has shrunk by 42, according to census data. The three-block town, nestled among the rolling hills 45 miles south of Spokane, is now home to fewer than 450 people.

But Oaksdale is about to grow up — in a big way: A new energy project with 500-foot-tall windmills is clearing its final hurdles, and Palmer believes it will usher in a new era.

“It was like pennies from heaven,” he says, praising the project’s potential to bring people back to town, to increase school enrollment and boost tax revenue. “We’ve got to keep our school here. If you lose your school, the next thing you know you’re just a wide spot in the road.”

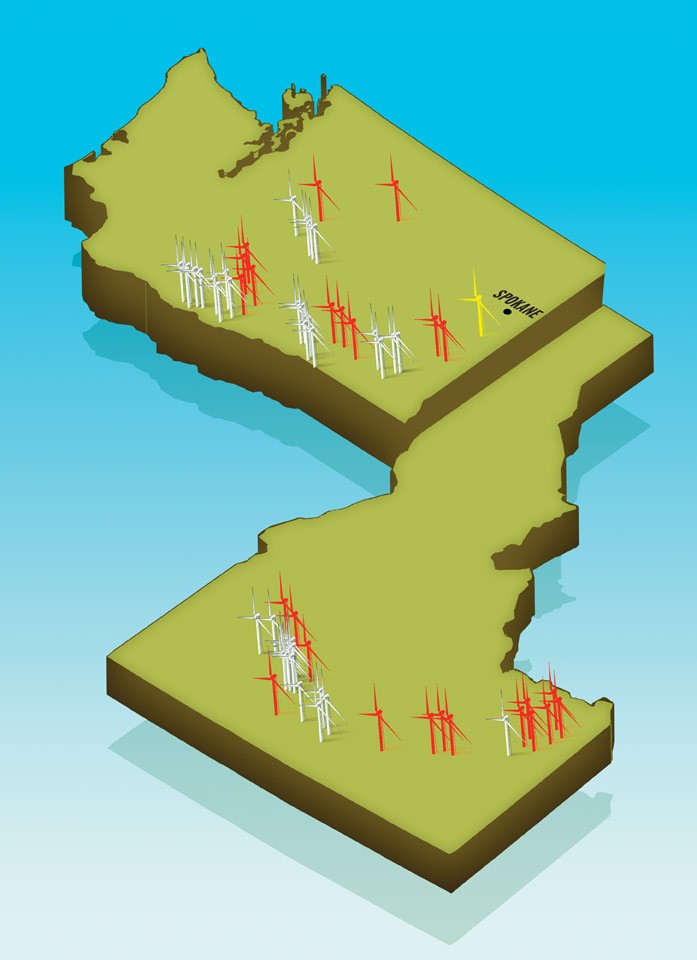

Wind power has already transformed parts of the Inland Northwest. A 149-turbine development is currently being built near Pomeroy, Wash. Idaho, meanwhile, has 18 wind farms generating power and 28 more on their way.

Indeed, wind has emerged as the country’s fastest-growing source of new energy, according to the federal Department of Energy. Although wind only accounts for about 2 percent of total power generation in the U.S., it has been on the rise ever since 1999, and jumped 33.5 percent from 2008 to 2009.

But wind energy isn’t without controversy or critics — a fact on display in Oakesdale.

Harnessing Mother Nature

The winds that howl across the Palouse can be destructive. Just ask lifelong farmer Ken Hanson. In 2004, it was surrounding him, his combine and his livelihood. A wall of black clouds dominated the horizon and he was helpless.

From inside his combine, Hanson watched a windstorm obliterate $70,000 worth of lentils in 20 minutes.

A year later, almost to the day, the wind struck again, this time taking his crop of barley — worth about $30,000. Insurance reimbursed him for none of it.

“It can be quite devastating,” says Hanson, 50, who’s been up by 5 am to work for as long as he can remember. “It’s like your boss saying, ‘You worked all year but rather than getting a paycheck, you’ll be getting a bill.’”

Now Hanson is looking to those gusts for a new kind of paycheck. He is one of 25 landowners who are leasing land to First Wind, a Boston-based company pursuing an expansive wind project on a ridge a few miles outside of Oakesdale.

“Wind has cost us enough,” Hanson says. “It’s nice to see it as a benefit.”

First Wind’s Ben Fairbanks says wind farms like Oakesdale’s have the potential to wholly transform small towns, to restore money and morale.

Fairbanks, the company’s regional director of business development, is tall, wears dark wraparound sunglasses and always has his Blackberry handy. Blocking the June sun with one hand, he steps out of a white SUV and points across the prairie to the ridge where as many as 65 wind turbines are expected to generate power by next year. The company looked at other sites in Eastern Washington, but this one was unique, Fairbanks says.

“The way the ridges are aligned is perfectly to the southwest prevailing wind, making it a pretty ideal site for wind development,” he says. Plans for the project began four years ago when First Wind installed test towers where it hoped to build.

The company already operates nine wind projects across the country and has three others under construction. The Palouse project is its first in Washington and is expected to produce about 40 megawatt hours of energy, enough to power 30,000 homes.

There’s not much wind blowing across the Palouse today as Fairbanks talks up the project, but he says that’s OK. A wind farm here is perfect for the region because it will harness the most energy during the winter, and leave the power-producing dams to do the heavy lifting each spring.

Over the course of the next year, First Wind expects to spend between $150 and $200 million on the project — about $30 million of which will be spent in Whitman County during construction, Fairbanks says. The company says it will create more than 100 jobs during the construction phase, and retain between eight and 16 positions for yearly operations, depending on how many turbines it installs.

Proponents of the project tout the much-needed revenue it will bring to town. First Wind says it will pay the county an average of $800,000 a year in property taxes. The landowners leasing pieces of their land will make money during construction (the amount depends on how many turbines are going on their land) and $8,000 to $15,000 a year once the project is operational.

For many, it’s a win-win windfall. But others remain unconvinced.

Fighting the Power

Marcia Wagner, 67, will never leave her farm. It’s land that has been in her family since the 1930s, but it currently sits idle, dedicated entirely to the Conservation Reserve Program, a government program that pays farmers not to farm. She loves the land and she’s not going anywhere.

Wagner and 16 other landowners adjacent to the First Wind project appealed it during the early stages, arguing that the look of the looming structures would destroy their property values. After their first appeal was rejected, they didn’t press on because of the expense.

It was “a David and Goliath situation,” Wagner says. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s a done deal. You can’t fight that kind of power.”

But not all the Davids put down their slings. Roger Whitten filed his own appeal of the project.

“My property is being destroyed, I’m being pushed off my land, and the government is just pretending nothing is happening,” says Whitten, 50, who lives on 13 acres four miles west of town.

Whitten is unyielding in his fight against First Wind and Whitman County, but he says he doesn’t have enough faith in the system to be hopeful. He estimates he’s put in about a thousand hours in the three years he’s been challenging First Wind.

“This is not only a property-rights case, but also a study in how government should not work,” he says.

He’s appealing the conditional-use permit the county issued First Wind last month — the final go-ahead for construction. Whitten sees his as a case of a big company in search of profits pushing around a lone citizen.

While critics of wind energy claim that projects similar to First Wind’s have detrimental effects on wildlife, and even the climate, researchers are divided. For his part, Whitten argues that the low-frequency noise from wind turbines will disturb his sleep enough to cause health problems.

The medical community remains divided on the impact of the low-frequency noise emitted by commercial wind turbines. Some say it’s harmless — no louder than the hum of a refrigerator. Others say it may not damage the ear, but it is annoying enough to disturb sleep.

In his argument against the permit, Whitten cites the work of Dr. Michael Nissenbaum, who studied a First Wind project in Mars Hill, Maine.

“The physical scale of the industrial wind turbines used today is relatively new and we are only beginning to learn, as physicians, about the presence or absence of negative health effects that may result from poor siting decisions,” Nissenbaum writes in an affidavit supporting a group of citizens that opposed the wind farm in Maine.

Whitten is looking to change noise ordinances in the county or state, or to be compensated for his land. But in its Environmental Impact Statement, First Wind cites scientists and reports that claim the noise is not enough to disturb locals’ quality of life or decrease property values.

Whitman County Planner Alan Thomson, who has led the county’s work with First Wind, says he and other officials have followed all legal requirements and don’t expect Whitten’s appeal to be upheld. Since a local judge recused himself from the case, a judge from Lincoln County is scheduled to hear Whitten’s appeal on Sept. 12.

“We have listened to and understand Mr. Whitten’s concerns, and we feel like we’ve adequately addressed them,” says Fairbanks of First Wind. “We will continue to move forward.”

Dam Nation

Avista, the region’s largest utility company, is buying the argument for wind. Late last month, Avista signed a 30-year contract with First Wind to purchase the energy produced from the Palouse project and distribute it to its customers, who range from central Washington to the Montana border and south to Moscow, Idaho, says Anna Scarlett, an Avista spokeswoman.

The deal, which was struck after a competitive bidding process, is “the right thing to do at the right time to do it,” Scarlett says.

It’s also what Avista has to do, according to Washington voters. Initiative 937, passed in 2006, requires larger utility companies to increase their dependence on renewable sources of energy: wind, wave, biomass and solar, among others. At least 15 percent of their total energy mix must come from these sources by 2020, with benchmarks along the way. The catch for a company like Avista, which relies heavily on dams, is that hydroelectricity facilities don’t count under the new law.

Avista gets 50 percent of its power from hydro, followed by natural-gas-fired electricity generation and coal. Last year, just 2 percent of its power came from wind, and the rest from biomass and other small projects.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, Washington produced almost twice as much hydroelectricity as any other state in 2010. It provides 31 percent of the nation’s total hydropower.

Still, Avista has to reach the 15 percent mark with other renewable sources. And so far, so good. The first benchmark arrives next year, when utilities must reach a 3 percent renewable-energy mix. Avista reached this by updating some of its infrastructure and buying renewable-energy certificates, which companies producing green energy sell to those that aren’t.

The next yardstick arrives in 2016, when companies must show that 9 percent of their power comes from renewables. The Palouse Wind Project near Oakesdale is expected to propel Avista all the way to that target.

Avista officials say they’d be moving toward wind even if they didn’t have to, despite the fact that the company was the second largest donor to the “No on I-937” campaign with $50,000.

“We had wind in our integrated resource plan before I-937 was the law in the state of Washington,” says Bob Lafferty, Avista’s director of power supply. “I-937 is really just a slight modification of maybe the timing of some of those plans.”

Lafferty says it’s likely to be more wind projects that carry Avista through to the full 15 percent.

While Avista executives are polite about the stricter standards, Inland Power and Light CEO Kris Mikkelsen doesn’t bite her tongue. She says the regulations are unfair and shortsighted.

Inland, a cooperative born in the ’30s out of a need for energy service to rural areas, serves only 40,000 electric customers in Eastern Washington and North Idaho but faces the same state requirements as Avista with its 360,000 electric customers.

The small utility has an extra challenge: While Avista gets credit for improvements to company-owned dams, Inland uses federally owned dams and gets no credit for improvements to those facilities.

Plus, the region doesn’t need more power and it doesn’t need wind farms, she says.

“I have a huge amount of sympathy for communities where these projects are being built because it creates revenue, but we just shouldn’t be building generation plants we don’t need,” Mikkelsen says. “These renewable-energy standards are forcing us to build so there are enough pieces of paper.”

Those pieces of paper are the renewable-energy certificates that Inland, like Avista, has purchased to meet the 2012 requirements. They come from projects in the region, many in western and southern Washington.

But this simply adds insult to injury, Mikkelsen says, because Inland is already a primarily renewable company. It receives 81 percent of its power from hydro and 2 percent from wind, but it still has to purchase renewable certificates or find projects to meet the requirements.

That comes with a lofty price tag, she says — one that customers will really feel by 2016 if something in the law doesn’t change.

“My main concern is about keeping electricity affordable,” Mikkelsen says. “I walk through our billing department once or twice a day and hear people on the other side of the phone having trouble paying their bills, so it really bothers me to have laws cause bills to be higher than they need to be.”

Wind-Dependent

Chris Marr, a former state senator, says he supported the initiative when it passed but has since realized its shortcomings.

Marr says I-937 passed because of strong backing from the wind industry, not because it was truly the best policy for Washington. The initiative doesn’t give enough allowances for new technology, non-wind sources of clean energy or conservation, he says. Besides, he adds, it was really just an environmentalist effort to push dams out of Washington’s energy portfolio and give wind — their preferred renewable — an edge.

“There are good alternatives, but we’ve already chosen who the winners and losers are in renewable energy,” he says. “This approach that says wind is the energy of the future and we should replace all other sources of energy, including dams that hurt fish, is unrealistic.”

Danielle Dixon, a senior policy associate at the NW Energy Coalition, which pushed for the initiative, doesn’t see it that way. It’s not an initiative about wind, she says, but one about diversifying energy.

“We have an amazing foundation of hydro in Washington, but hydro is a mature technology,” Dixon says. “Rather than putting all of our eggs in the hydro basket, we’re building upon that foundation.”

Marr maintains he’s “not saying wind energy is bad,” but worries about too much dependence on it.

Wind turbines are often produced overseas, their transport and set-up generates a large carbon footprint, and the energy is dependent on when the wind blows, so it’s less reliable than things like hydro or geothermal energy, he says.

Not to mention, he adds, it’s expensive.

“You’re going to drive a rate spike, and that’s what were staring down the face of right now,” Marr says. “Wind acquisition is very expensive.”

Contracts with projects like First Wind mean Avista will raise its rates to cover the associated costs, Lafferty says. At a time when the economy is sputtering and jobs are scarce, Avista has already faced criticism for high rates and stable profits.

If voters channel anger over rates into a new initiative to change I-937, Marr worries they could end up stripping Washington law of any renewable energy requirements, which he says would be detrimental to the environment. He hopes legislators, “who have the time to be thoughtful,” will change renewable-energy requirements for the better before it’s too late for customers.

Next door, Idaho doesn’t have renewable-energy requirements. In 2005, the state began offering deep tax breaks for wind companies, causing a spike in projects there. This year, some legislators argued the breaks were too high. Idaho wasn’t seeing enough benefit from an influx of wind energy, they said, and projects should be stopped for at least two years. But the effort failed and wind energy is still growing in Idaho’s southern desert.

No Guarantees

Leaders in the wind industry hail projects like the one near Oakesdale as economic boons for host towns, but resource economist and WSU professor Phil Wandschneider warns against their temporary nature. One project can only do so much: a few construction jobs, a short influx of people and then only a fraction of them left to actually run the facility.

“You’re not going to build a wind industry,” he says. “You have a construction project.”

Fairbanks, of First Wind, says there are no guarantees of expansion. He says his company isn’t ensuring the future of the Palouse as the new Mecca of wind energy.

But for its supporters in Oakesdale, the project is a revelation. From City Hall down the street to the town’s only coffee shop, the project’s staunchest supporters are confident it will give the region a much-needed jolt.

Margaret Leonard owns the Country Attic on First Street, a yellow metal building with antique furniture, country décor and a red door that squeaks when customers enter — which isn’t often. There’s not much around here, Leonard says, so there’s not much reason for people to come her way.

She now believes the wind farm will bring jobs and tax revenue to the quiet county, something she says it desperately needs. As retirees from Rosalia, Wash., Leonard and her husband work about 40 hours a week at the shop, but couldn’t support a family on the profits, she says.

Leonard, who wrote the county a letter of support for the project and spoke during the public comment period, says when it comes to those in opposition, she and her neighbors just have to be patient.

“That’s when we just have to respect our differences,” she says.

Across the street from City Hall, in a small, second-story office space that smells of new drywall, Fairbanks says differences of opinion are to be expected when a new company comes to town with big plans.

“First Wind is not a household name,” he says, but soon, around here, it will be.

Comments? Send them [email protected]