Dreamy ambient music plays quietly overhead as 13 fourth graders at Longfellow Elementary School in northeast Spokane slowly make their way from tables scattered around the library to a cozy conversation pit in one corner of the room. Once they settle into their spots on the carpeted stairs, library teacher Joseph Arnhold projects a picture of the elusive Pacific Northwest tree octopus onto the screen behind him.

"Does anyone know if these are real?" Arnhold asks the class, pointing to a webpage created decades ago that details the alleged species and its habitat.

"No, because octopuses live in the ocean," one student answers as others chime in with a chorus of giggles and their own answers.

"What do you do when you're not sure if something is or isn't real?" he asks.

"You look it up on other websites?" another student responds tentatively.

"You got it," Arnhold replies. "Is it good or bad to create something that isn't true?"

At this point most of the 9- and 10-year-olds answer with a resounding, "Bad."

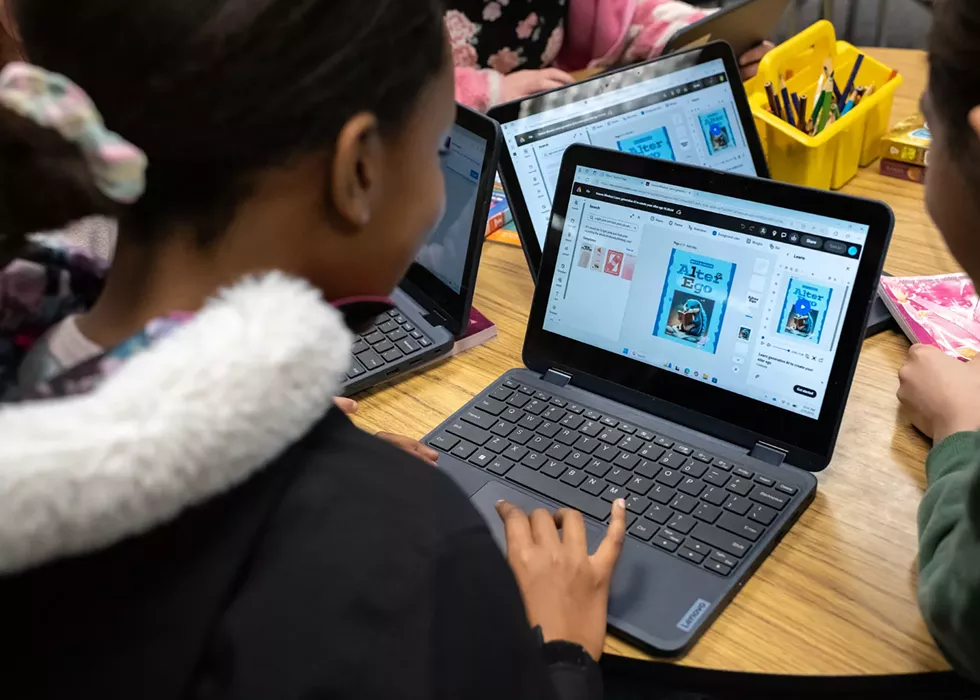

These questions may seem simple or even silly, but they're actually a way for Arnhold to teach students about media literacy and to get the class thinking about how they can validate sources for information they may see online. As a fun activity afterwards, he instructs the students to use an image generator in Adobe Express to imagine their own pretend creatures, much wilder than tree-dwelling octopi.

Artificial intelligence, or AI, has been in use for decades. It's used by the spam filters on our email accounts and to compile the recommendations we get on streaming or shopping apps. However, generative AI programs that collect and use massive amounts of data to answer questions or generate new text and images, are relatively new additions to the world and even newer to our education system.

Last year, Washington became one of the first states to release guidelines for using these tools in K-12 schools. Since then, educators and students in the Inland Northwest have embraced this technology in the learning process.

As a library instructor, Arnhold's job has always been to introduce students to new ideas and to teach them how to become independent learners. And though he's been in the role for the last five years, this is the first year that his instruction has included generative AI.

"Generative AI is just one more form of media that we have to teach kids how to interact with, so our library information specialists kind of lead the charge around media literacy instruction in our system," says Emily Jensen, one of Spokane Public Schools' curriculum coordinators. "It's going to become more and more ubiquitous, and something that more and more people in our system are integrating into how they teach."

Introducing a new tool can be challenging, especially if it's as complicated as AI, but Arnhold says it's easier when young students have the opportunity to play while learning — which explains the mythical dragons and baby blue otter-squirrel hybrids beginning to appear on some students' Chromebook screens in the library.

"If even a fourth grader can understand how to use AI, anyone can," he says.

'ONE STEP BEHIND'

While generative AI is now being embraced by educators throughout the state, it was first supported by students looking for ways to cheat, says Betsy Lamb, Spokane Public Schools' director of learning technology and information systems.

"They would copy their homework [questions] and then just grab the answer and submit it. And of course, the first thing we heard from teachers was 'Hey, how do we even handle this?'" Lamb says. "Students are fearless, and they will push boundaries, so our job is to stay one step behind — hopefully just one."

In other words, teachers may never be able to stay ahead of these changes, but they can try to keep up with pioneering students. This required swift work on the district's part to figure out how these AI programs could become a valuable learning tool, rather than something educators needed to ban. As those conversations were happening in Spokane, leaders at the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, or OSPI, were also considering how to approach AI.

"I think what became obvious to us is how much students were already using this technology. We may not have even known it was called AI," Washington Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal says. "But generative ideas, generative creation is something this generation of learners has been into for a long time, and so they're truly the digital natives here and the adults are not."

Students are fearless, and they will push boundaries, so our job is to stay one step behind — hopefully just one.

That realization is why he instructed his team in 2023 to begin researching generative AI and its potential uses in the classroom, with the goal of releasing guidance for all of the state's schools. Beyond getting a basic understanding of these programs and fostering a universal approach, Reykdal hoped to find ways they can be used as educational tools, similar to other emergent technologies through the years, such as cellphones, computers and even calculators.

"We had districts trying to ban it right away and just kind of jump to conclusions, so we really wanted to slow that down and come together," he says. "If [teachers] spend all their time trying to police what kids produce, we're going to be back where we were with the calculator. I mean that was actually a controversy at one point in our country."

"The calculator did not destroy math, and AI will not destroy learning," Reykdal adds.

STATEWIDE SOLUTION

By January 2024, Reykdal's office released guidance stating that generative AI in Washington schools should be used in a human-centered way. Though this approach mirrors some of what other states were trying at the time, Reykdal says OSPI's recommendations painted a fuller picture.

In OSPI's framework, titled "Human Inquiry-AI-Human Empowerment," teachers need to show students how to input precise prompts into these programs for the best results. Afterwards, they need to teach their students to understand what the AI generated, and then how to properly edit it for their work.

"On the front end has to be human inquiry, on the back end has to be human question," Reykdal says. "If we do that right, I think this technology will land really well, and it'll be a positive thing."

Since then, OSPI has released more resources for how teachers can begin using these tools in their classrooms, along with advice on the ethical considerations for AI use. One of the agency's main concerns is bias.

With statewide guidance out on the table, Spokane's school district began to work on its own generative AI strategy. This includes hosting professional development classes for teachers and administrative staff, alongside written guidelines for how these tools can be effectively and ethically used in the classroom.

Lamb, who helped draft the districtwide guidance, says privacy is one of the most important pieces for teachers and students to consider when using generative AI programs. For example, teachers should be cautious when using AI to draft individualized education plans, or IEPs, which include private information about students. Teachers in the district have access to an IEP generator tool, which only asks for a student's grade level, disability category, and a description of their behaviors, needs, and strengths. They are prohibited from entering personal student data such as actual names.

"You have to be really careful about what you put in there, about yourself or anyone else," Lamb says, "and that's something we have to teach our kids, too."

Additionally, Spokane Public Schools does not consider anything that's been produced by AI to be original work, so students and staff are required to cite their source as they would attribute a quote to an article or book. In fact, major style guides, including MLA, APA and Chicago style manuals, have all published preferred ways to cite AI responses. The district also asks students to keep a record of the prompts they input and the tool's corresponding outputs, so they can show their work to their teacher.

"If a generative AI tool is crafting something, you can absolutely tell," curriculum coordinator Jensen says. "Two years from now those tools may have progressed to the point where we can't tell, but right now you can."

Often, the formatting gives away that generative AI was used on an assignment, she says. Some programs pop out responses in bullet points, while others produce blocky paragraphs that flow unnaturally. Other times these programs will produce lengthy responses that say nothing of substance.

"You have to know how to construct prompts in ways that are going to be less likely to return biased results," Jensen says. "And then once you have your result, you need to go back and check for validity and accuracy."

Generative AI is making its way into Idaho schools, too. Last summer, Idaho Superintendent of Public Instruction Debbie Critchfield issued a press release titled "Artificial Intelligence in Idaho Classrooms: Friend or Foe?" She described it largely as a friend we need to get to know better.

"I'm in the camp that thinks we can make AI a constructive part of learning," she stated in the June release. "When used appropriately, I believe that AI can be a tool for both students and teachers."

And while the Idaho Department of Education has yet to release statewide guidance like Washington did, schools across the Gem State are already using generative AI programs. At the beginning of the 2024-25 school year, teachers in the Coeur d'Alene School District began using Magic School, a generative AI program created for educators.

At Spokane Public Schools, Magic School had previously been used by individual teachers, but at the beginning of the 2024-25 school year its use was officially approved for both students and staff. Earlier this year the district also approved the use of Khanmigo, another school-based AI created by Khan Academy, a nonprofit that provides online tutoring. Jensen says these programs are age appropriate and formatted to give an educator full control of how their students use them.

That control is only possible because Magic School is known as an AI wrapper, meaning it's a platform that houses generative AI models (such as OpenAI's GPT-4o, Anthropic's Claude and Google's Gemini) inside it.

"Teachers can customize which tools they're pushing out to their students with this program. So maybe I want to allow my students to take a paragraph that I have given them and rewrite that paragraph into language that's less complex. I want to give that tool to my students, but I don't want to give them access to a tool where they just get to go in and write any prompt that they want and get feedback from the generative AI," Jensen explains. "It allows for some really careful and protected training wheels."

APPLIED AI

Though it's still in its infancy, the potential of generative AI is seemingly unlimited. Jensen says that power is best harnessed for tasks that teachers either can't do themselves or don't have the time for.

"I've worked with teachers who will ask generative AI tools to write in the voice of a historical figure or a celebrity," she says.

"Also, part of what they're using it for is almost like a personal assistant as a time saver," Jensen continues. "A teacher could do those tasks for themselves, but it would take them minutes, hours, days to do sometimes."

Teachers often use these tools to take a lesson out of the school district's approved curriculum and modify it to their class needs. For example, if a text is written for students at the fifth-grade level, a teacher can ask Magic School AI to rewrite it at different reading levels for other students in their class.

"We have students who struggle as learners, and we have students who are high achieving, and our educators can provide for those students, but these tools can help them to modify more quickly," Jensen says.

Of the many potential classroom uses, Reykdal says he's most excited for generative AI to create an environment where every student has some form of individualized education. In practice, he says, educators would still teach students about the same concept, but one student might read about dinosaurs while another reads about geology.

"We now know that a lot of students don't get the key lessons and learning standards because they're bored or uninterested in the content," he explains. "Gone are the days when every student reads the same book at the same pace."

In the long term, Reykdal says this individualization could potentially save money for school districts that no longer need to buy complete sets of curricula, which generally include textbooks, novels, worksheets, lesson plans and other guides for educators to teach a subject. For example, a school could potentially forgo buying 30 copies of the same book and instead use AI to tailor lesson plans to individual books for each student.

In the short term, it's beginning to transform education as we know it. Instead of cramming kids' brains with hours of required content, teachers can introduce topics and then help their students discover more about those topics using generative AI.

"It's turning educators a whole lot more into learning evaluators than content deliverers," Reykdal says.

While Washington's K-12 public schools have been operating under the same guidance for the past year, those working in higher education have been left to fend for themselves. Colleges and universities across the state have implemented policies and guidelines surrounding generative AI, but each school applies its own rules.

Even though many of the recommendations at state universities are largely the same — professors have autonomy over generative AI usage in their classes (including banning its use), personal data should never be input into these programs, and students need to cite their AI sources — there isn't universal guidance from the Washington Student Achievement Council, the statewide agency that oversees higher education.

"I wish higher ed would have seen our stuff and jumped on it sooner. We saw them sort of panic about students cheating at first," Reykdal says. "I think they've mostly come around now to realize they're going to have to embrace the reality of this, but it forces them to teach differently."

HIGHER EDUCATION LANDSCAPE

Over the last few years, Travis Masingale, associate professor of design at Eastern Washington University has placed himself at the forefront of the generative AI push in higher education. After ChatGPT came out in 2022, he spent a year learning the program and its practical applications for educators.

However, when he began giving talks to his colleagues about AI last fall, he found that convincing others that these tools could and, he argues, should be used in the higher education landscape required more thought.

"I spent a lot of time wondering, 'How am I going to convince these scientists and mathematicians and engineers that AI is coming and they should be using it?'" he says. "I don't know if anyone was sold at the time, but I decided to talk about using it to reformat the Pythagorean theorem to football players determining the arc of a football needed to kick a field goal."

After those initial talks, Masingale says he spoke with Eastern's Academic Integrity Board, a faculty committee that determines how the university should respond when students are caught cheating. At the time, he says the board was considering an investment in detection software the university could use to see if student work includes generative AI.

"My advice to them was, 'That is the wrong answer,'" he recalls. "We should invest in how to teach students to use this technology because this is going to be the world they live in and work in."

Since then, the university has released its own guidelines on generative AI. While professors can allow or prohibit the use of generative AI in their classes, Eastern urges them to avoid AI-detection programs altogether.

"Their efficacy is questionable and false positives and biased results are common," the guidance states. "We do not recommend that instructors rely upon AI detection tools to identify usage of generative AI and, instead, encourage faculty to engage in conversation with their students about appropriate (and inappropriate) usage of generative AI for their courses."

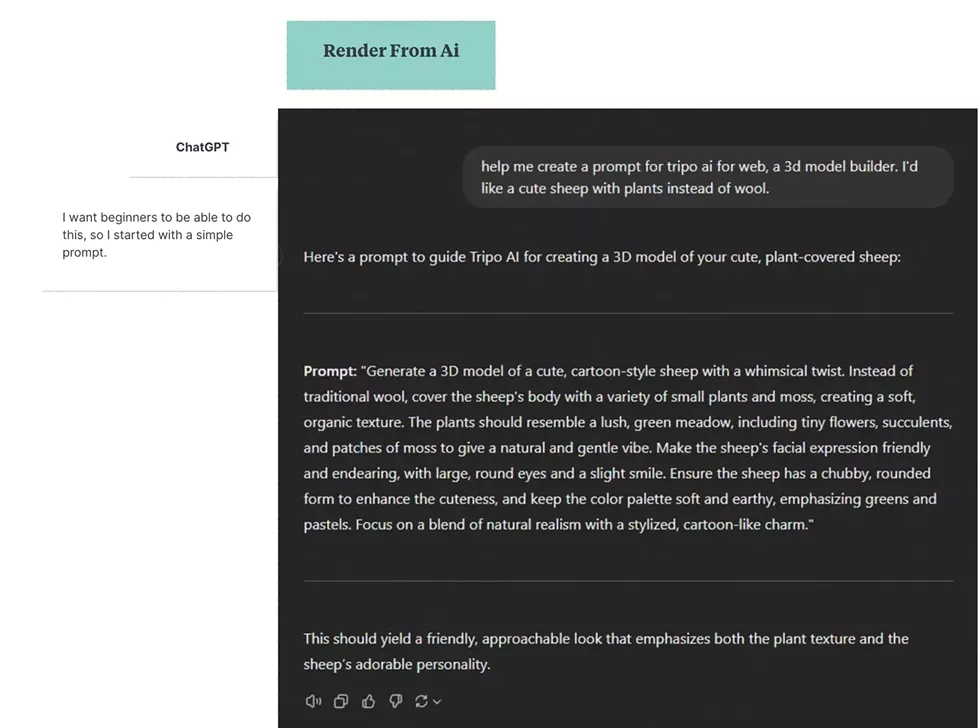

In Masingale's web design classes he teaches students to understand coding enough to create their own website. Then toward the end of the quarter he shows them how generative AI tools can make that process easier.

"I often say that critical thinking is even more important when using AI, especially in web design," he says. "They have to be able to read the code to do that, and like any good programming, the better your inputs are, the better your outputs will be."

He also teaches an Emergent Design class focused almost entirely on technologies like generative AI. In this class, Masingale always begins by teaching basic prompting techniques. These include asking simple questions of the AI, which helps students understand the types of responses it produces. Then he gets into the prompting techniques that help these programs create more advanced results. It's best to use clear and specific prompts that include relevant context, such as the intended audience and the appropriate tone. (Two of Masingale's students' projects are featured here.)

A weak prompt may read, "Tell me something about AI and the environment," according to a 2023 prompt design project by Antoni Carlson, one of Masingale's students. Carlson noted that a well-structured prompt might read, "Create a summary of the latest research on the use of AI in environmental conservation. The summary should include key findings, methodologies used, and potential applications in real-world scenarios. Please limit the summary to about 300 words and ensure it's suitable for an academic audience."

"I'm definitely more of a guide, because I can't know it all," Masingale says. "There's just too much. It's happening too fast. So I kind of show them how to use AI to teach themselves stuff or move in the direction or find their resources."

Once students know how to best prompt these tools, Masingale lets them practice with image generation projects until they've got the hang of it. By the end of the quarter he expects his students to complete self-led assignments based on what they're interested in.

"One of the coolest things I saw a student do last quarter was basically using AI to analyze user interface components of accessibility for colorblind and contrast ratios," he says. "Other students are creating animations for short, little narratives. I let them play around with these tools because I'm really interested in not what graphic design can we replicate, but what we can do next with AI."

Some student projects detail how beginners can use generative AI to create 2D and 3D models, while others delve into AI-generated video game designs.

Masingale also sets aside time to ensure his students understand the risk of getting caught up in an echo chamber of sorts.

"It's a piece of technology that's designed in a way to keep you engaged with it, so I ask my students to be critical of it when it's making you feel really good about whatever your idea is," he says. "That's a reality check to start checking its responses and ask it to be more critical."

This is the kind of guidance he hopes to impart on more than his design students in the coming years, as he's proposed building beginner, intermediate and advanced AI Literacy courses at Eastern. If all goes well, he says, these classes would begin in fall 2025.

CAUSE FOR CONCERN?

Not everybody is on board with the use of these programs, SPS's Lamb says. Some students are refusing to use the tools outright, and she's heard from colleagues who worry the technology might make their jobs obsolete.

"AI will always be a tool to complement teaching, that human connection and relationship that is part of the foundation of education. A teacher knows their students so well that AI could never replace that, to know what a kid truly needs for successful learning," Lamb says. "In my mind, AI can't replace the staff we currently have, but someone who uses AI well, might. That person is going to get ahead and be more sought after than somebody who doesn't have that skill set."

Though these new tools are being used to help students learn virtually, her colleague Jensen says in-person instruction will never go away.

The calculator did not destroy math, and AI will not destroy learning.

"If anything, COVID taught [us] that online-only is not the healthiest option," she says. "You know, four years later, we are still grappling with supporting students through essentially the trauma that they went through during that online learning piece."

There's also an intense environmental impact to consider with the use of generative AI. In 2022, nearly 2% of the global electricity demand was consumed by artificial intelligence and data centers, according to the International Energy Agency's 2024 electricity report. The agency estimates this energy use will double by 2026, roughly rivaling the electricity consumption of Japan.

However, the impact to our energy grid is something at the forefront of state Superintendent Reykdal's mind and, he argues, is something Washington is prepared to handle.

"The energy that it is going to take to power [generative AI] for the next decade is real, so states that lean into this and want to lead in some ways are going to have to be ready to either produce energy or to acquire energy in an affordable way," Reykdal explains. "We have that in droves here with our [hydroelectric power production] in Eastern Washington, our lower power costs, and we've got land galore."

Though challenges around student use of generative AI arise frequently, Spokane Public Schools spokesperson Ryan Lancaster instead worries about those schools that have completely avoided the tools.

"I look at other districts elsewhere in the country that are basically clamping down on this right now saying, 'We're not going to use these tools until things are settled,' which they never will be," he says. "I fear for those students and those staff, because those kids are going to be behind. It's like banning the internet or banning social media, which never worked for anyone." ♦