Who the hell is in front of me at this stoplight, and why do they have California plates?

If you wanted to answer this question in Idaho before the summer of 2023, you'd have to do a lot of digging. And then, once you found the data you were looking for, you'd have to figure out how to understand it.

Luckily, that's not an issue anymore. In June, Idaho Secretary of State Phil McGrane hired Gabe Osterhout to work in the newly created position of "data visualization specialist" to dig through a ton of previously unexplored data. Before being elected to his statewide office, McGrane worked as the Ada County clerk in Boise, where he had a data visualization specialist on staff — and where he got the idea for the same position at the state level.

"We just had this treasure trove of data," says Osterhout, who previoulsy worked as a researcher with Boise State University's Idaho Policy Institute. "The stuff we're presenting has always been publicly available, but not in a way that was easily digestible."

So Osterhout set out to transform tons of data just collecting dust into something more visually appealing and easily understandable. Since the data came from voter registration forms, much of it was basic information, such as party affiliation, age and county of residence.

But, with a bit more digging, Osterhout uncovered a gem. Thanks to an optional question on voter registration forms about previous residences, he found a cache of information on people moving to Idaho.

Even though it's an optional question, Osterhout says there's a large enough sample to be considered important.

"This information wasn't necessarily available before," he explains. "That even includes public records requests."

What it showed probably won't surprise you: There are more former Californians in North Idaho than from any other state (other than Idaho). Almost 40,000 of them to be exact. Perhaps that's to be expected since California has a population comparable to countries — like Canada and Australia.

The number of registered voters who reported moving to Idaho at some point from elsewhere is 118,702. That's about 12% of the state's total 996,941 voters.

One flaw in Osterhout's data is that it isn't time-stamped. That is, it's a snapshot of Idaho's current voter pool. These numbers reflect currently registered voters, whether they registered to vote in 2023 or in 2003, when the state took over managing elections from individual counties. Osterhout says when someone who previously voted in Idaho registers to vote in another state, their Idaho registration is discarded.

The other top states that folks come to Idaho from are Washington (20,199), Oregon (9,178), Utah (7,308) and Arizona (4,371). Speaking of Washington, more people have moved to Idaho from Spokane than from than any other U.S. city. A recorded 2,045 former Spokanites are registered to vote in the Gem State, 1,069 of them in Kootenai County alone.

"The very thing that people come here for is being ruined by the same people coming here."

Osterhout's data visualization allows folks to interact with it as a map on the Secretary of State's website. We can see which counties in Idaho folks are moving to and what cities they're coming from. For example, almost 1,000 people moved to Idaho from San Diego, and 130 of them live in Kootenai County.

We can even get into the demographics of folks coming from each city. Like the single voter who moved to Kootenai County from Ontario, Oregon, isn't affiliated with a political party and is between the ages of 30 and 49. Or the two voters from San Martin, California, who are both older than 70 years old and registered as Democrats in Kootenai County.

Because of this we can debunk a myth while telling you something you probably could've guessed. All these new Idahoans aren't Democrats coming to liberalize the Gem State. In reality, most of the people moving to Idaho are Republicans. In the case of those Californians, almost 80% of them registered in Idaho as Republicans. (By contrast, only 58% of the state's nearly 1 million voters are registered as Republicans.)

"We got some big numbers that mean we can really understand just how conservative those Californians are. ... Many consider themselves political refugees from their home state," Osterhout says. "A lot of us who study this always knew this was true."

The Idaho Secretary of State's Office's data release is only meant to share what the state has. Osterhout says it's up to citizens to choose how they'll interpret it.

WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Just to dispense with the obvious, people are moving to the Inland Northwest, and in great numbers.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Idaho's population grew from 1,571,450 in 2010 to 1,939,033 in 2022, a 23% increase. Kootenai County — home to Coeur d'Alene — saw an even bigger boom. In 2010, it had 138,494 people. Twelve years later, 183,578 lived there, a 32% increase.

While Washington saw a bigger increase in raw number of people, it was a markedly smaller proportional increase in the population. Washington's population grew from 6,744,496 in 2010 to 7,785,786 in 2022, or about 15%. Over the same time, Spokane County went from 471,221 in 2010 to 549,690 in 2022, nearly 17%.

If you ask Travis Hagner, a political science professor at North Idaho College, all this data collection can be boiled down to a question we've been asking forever: Why do people move?

The Idaho data points toward an ideological pull toward Idaho, but Hagner says that's a large claim for such a relatively small amount of data.

"The general consensus would be, yes, it's looking like there's been a shift of people moving for ideological reasons. But, historically, ideology hasn't been a deciding factor to move to a state — it's been the cost of living," he says. This data, however, only points to folks moving for the cost of living in some cases. The top cities moving to Kootenai County from California and Arizona — San Diego and Phoenix, respectively — both have higher costs of living than Coeur d'Alene, according to Zillow. The top cities moving to Idaho from Washington and Utah, Spokane and Salt Lake City, have lower costs of living than Coeur d'Alene.

Realistically, Hagner says what's happening is closer to the self-sorting that happens in a high school cafeteria. People want to be around like-minded people.

"Without the data to support these assumptions, it's just a pretty picture," he says. "I think we can get to the truth, rather than getting to the gut feeling around here that 'those people from California are moving here and bringing their politics.'"

However, he does think that it's possible to get that information.

"It wouldn't be that hard," he says. "When people fill out a voter registration, we could have them fill out a short survey, too."

Some may worry about giving up too much of their information to the state. Hagner thinks if this theoretical survey wasn't anonymous, it wouldn't get enough true answers.

"People don't like to make other people angry if they can help it, so they will often answer surveys how they think the provider wants them to feel," he says.

But for legislators to introduce good public policy that will affect all citizens, they need to actually know what their citizens want, Hagner says.

Whether that's something more ideologically aligned with the new Idahoans, or ways to combat increasing housing, transportation and energy prices is still unknown, at least according to Hagner.

WHAT ABOUT WASHINGTON?

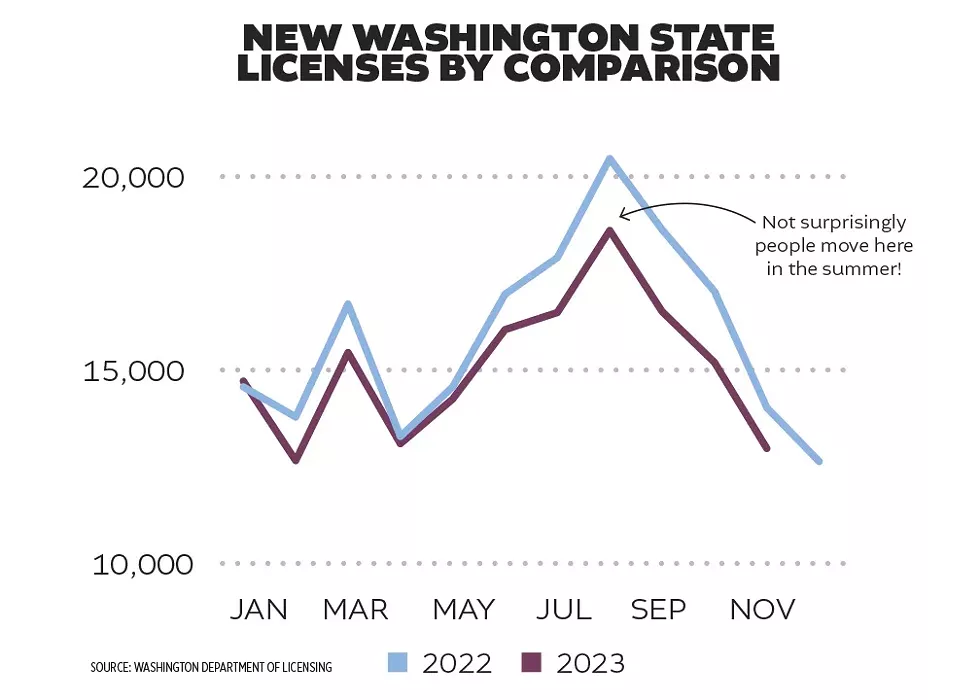

Across the border, Washington doesn't track migrating voters. Instead, the state has information of a different, yet still mobile, kind: driver's license data.

"The data that we look at in Washington is typically only a part of the whole story," says Mike Mohrman, a demographer with the state who does forecasting for the Office of Financial Management. "But looking at this driver's license data gives us a good look at where people are moving to."

The Washington Department of Licensing requires newcomers to get a state license within 30 days. And it records where folks come from. By looking into this driver's license and ID card data, we found some similarities to Idaho — more Californians moved to Washington than those moving from any other state. And we know when they moved here.

Between January 2022 and November 2023 (the most recently available month of data), more than 65,000 Californians obtained a Washington state license. About 3,000 of them received their license in Spokane County.

"Many consider themselves political refugees from their home state."

Washington's other top in-moving states are Oregon (35,997), Texas (21,188), Arizona (14,135) and Idaho (11,501). Many of the people moving to Washington settled in the Puget Sound area along the I-5 corridor, in King, Snohomish and Pierce counties.

Of the 11,503 drivers who moved from Idaho between January 2022 and November 2023, 3,293 transferred their license in Spokane County. Conversely, only 3,244 of the 67,068 Californains who transferred their licenses to Washington chose to live in the Inland Northwest.

In that time, Washington transferred a total of 356,645 licenses, only 21,649 of them in Spokane County, which is the fourth-most populated county in the state. (As of 2022, there are about 7 million total driver's licenses and ID cards in Washington.)

Like Mohrman says, this data only tells part of the story. Folks moving to Washington who don't drive, or choose not to get an ID card for whatever reason, won't be counted. It also doesn't say what cities people are moving to, or why.

While the data in Washington doesn't reveal much about the in-movers, Spokane Realtor Marianne Bornhoft says many are moving to Spokane County for the lower cost of living. People moving from California often can buy a house with double the space for the same cost, she says.

"People moving to town are wanting a better quality of life," Bornhoft says. "I think this is the land of opportunity — people are capitalizing on that and the lower price points."

Bornhoft herself moved to Spokane from Portland about three decades ago and has no regrets.

"It's really great seeing people discover Spokane," she says. "I'm really proud to live here."

BUT... WHY?

"I woke up this morning and it was -8 degrees out," says Michael Wendland. "But then, I look at the lake and the snow-covered landscape, and I just fall in love with the place where I live."

Wendland grew up in Coeur d'Alene and graduated from Lake City High School. But after graduation, a time when many young adults decide to move away from home, he decided to stay.

In 2012, Wendland got his real estate license. Now, more than a decade later, he's president of the Coeur d'Alene Regional Realtors and still helps folks find their own little piece of North Idaho.

With more than a decade of experience under his belt, Wendland has a keen sense of the market's trends, especially when it comes to out-of-staters.

Like with many recent trends in our nation, Wendland says a lot of North Idaho's migration growth stems from the pandemic.

"When COVID happened, people were flocking to Idaho from Western coastal states based on our loose rules during the pandemic," he says.

But that's not the only reason.

"Prior to the COVID craze, some [migration was] politically driven, but a lot of it can be tied to quality of life," Wendland says. "We still have that small town feel."

But will it last?

David Callahan, Kootenai County community development director, says that some people move to the area for its natural appeal and its allure to those who want to live a more recreational life. Overall, though, he says many move to North Idaho to avoid the congestion of the cities they come from.

But that desire to move away from the city has in turn effectively created the very places they hoped to escape.

"I'm seeing a repeat experience of what I experienced in Boulder, Colorado, when I lived there — the tragedy of the commons," Callahan says. "The very thing that people come here for is being ruined by the same people coming here."

Idaho is one of the least-densely populated states in the nation — and even counting the recent growth, it still is — but the ongoing influx of out-of-state movers has had an effect on that small-town feel.

"The general consensus would be, yes, it's looking like there's been a shift of people moving for ideological reasons. But, historically, ideology hasn't been a deciding factor to move to a state — it's been the cost of living."

The main impact is on the housing market. Wendland, the Realtor, says many of the folks moving to Idaho are retirees who sold their house in their home state and were able to make a large down payment on property in the Gem State.

More than two-thirds of the voters moving to Idaho are older than 50, according to the Idaho data.

"We do see multiple issues with the limited inventory and space in the area," he says. "We're still in a housing shortage, but just about every organization in North Idaho is looking for solutions."

Folks are seeing these issues come up as an increased cost of living and even minuscule changes to their commute times, not just in Idaho, but in Washington, too.

For homebuyers, that looks like a nearly $150,000 jump in Spokane County's median cost of a home between 2019 and 2024. In 2019, the median home price was just under $250,000 and now, it's sitting at $390,000, according to Redfin. Kootenai County saw a much larger jump, from about $281,079 in 2019 to $519,960 in 2024.

The average rental prices in Coeur d'Alene actually went down by about $225 from last year's average of more than $2,000. Even with the decrease, average rents in Spokane are lower by about $400.

In 2012, the average commute time in Kootenai County and Spokane County was recorded at about 21 minutes, according to the Census. However, in 2022, the average commute time increased in Kootenai County to about 24 minutes and in Spokane County to about 22 minutes.

And while folks aren't moving to Spokane County like they're moving to Kootenai County, it's easy to see why Washington may be enticing to newcomers, especially in Seattle's King County where more than 70,000 (seven times Spokane County) licenses and ID cards were issued.

Along with a long history as one of the most politically progressive cities, Seattle is the birthplace of national retail giant Amazon. The almost $20 per hour minimum wage in Seattle is also one of the highest in the nation. (Which probably helps since the average rent price is almost $2,100.)

No matter who you ask though, there isn't a one-size-fits-all solution.

"I think the biggest thing is responsible growth," Wendland says. "We love our Idaho, and we have to protect that, but we have to look

at some alternatives."

Wendland thinks Kootenai County could move from building homes on 5-acre lots to building them on 2- or 3-acre lots. That way folks still get that rural vibe from their property, and more are able to be built than before. (This is much different than what responsible growth looks like in Spokane. In recent years, rules on housing in Spokane have been increasingly loosened to allow more types of housing on more types of land.)

Callahan has been looking to other communities throughout the nation to find solutions to handle this growth but has been unsuccessful so far.

"I'm not comfortable yet saying what I've seen in other places will work here," Callahan says.

His office, however, just got authorization to update comprehensive plans and change some policies to adequately deal with growth in Kootenai County. And while it's too early to assess the impact of these potential changes, Callahan is optimistic that they lead to a better future for those who call North Idaho home — even if they just moved here. ♦