JUNE 20, 1994 — This is how it all ends: Four gunshots as steady as a heartbeat.

Pop, pop, pop, pop.

The third hits Dean Mellberg in his left shoulder, just a superficial wound. The fourth strikes square between his eyes. The blast sends his body soaring, feet splayed, straight into the air, like a stuntman's in a movie. He spins counterclockwise and lands on his back in the grass, his left hand still gripping the stock of his rifle.

Seventy yards away, Senior Airman Andy Brown lowers his handgun, a military-issued Beretta M9. Brown gets up from where he's kneeling and dashes for cover behind a small pickup parked across from the base hospital.

"Don't move!" he shouts.

When backup arrives, the medics rush to revive the man in the grass. They don't know who he is or what he did. They don't know how many lives he ended or how many people he hurt. The radio dispatcher alerts all patrols to a possible second gunman. Someone had called to report a sniper on a nearby building. Brown scans the roof, his sidearm drawn, as medics declare the gunman dead on the scene.

Meanwhile, in the hospital dining hall, 15-year-old Melissa Moe hides underneath a sink in a pool of her own blood, breathing hard, waiting for help. She's cradling 5-year-old Janessa Zucchetto in one hand. The other clutches her right thigh.

This is it, Melissa thinks. I'm going to die.

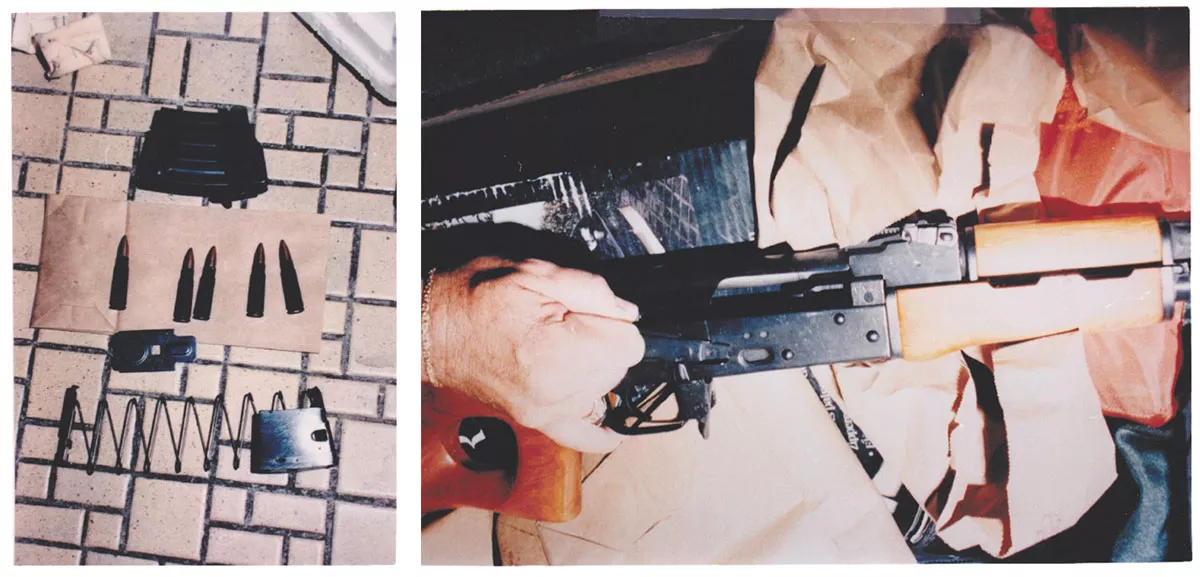

The gunman's story is a familiar one: Twenty years ago, Dean Mellberg, a disgruntled former airman, returned to Spokane armed with a MAK-90 assault rifle, the civilian version of an AK-47, and a 75-round drum. He arrived by taxi at Fairchild Air Force Base hospital with a murderous vendetta against the doctors he believed had slighted him — psychiatrist Thomas Brigham and psychologist Alan London. A year earlier, they had evaluated Mellberg, determined he was dangerous and recommended his discharge.

After 10 minutes of hell, four people and one woman's unborn child are dead and 22 are injured. Their lives and those of countless others — first responders who rescued victims, witnesses who attempted to save the dying, survivors who are left burying their friends — are forever changed.

For years, they bear the weight of survival. Some of their scars are physical, but many are hidden in mental health diagnoses: Depression. Anxiety. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Even after they grow up, start families and embark on new careers, they're reminded of that day whenever fireworks light up a sky, or when another mass shooting devastates another community somewhere else in the country.

They may not know the people of Littleton, Newtown, Isla Vista, Seattle or Fort Hood, but they know something of their grief — and of the search for meaning in senseless violence. Three months after the Fairchild shooting, Congress would pass an assault weapons ban that included the weapon Mellberg used. Ten years later, lawmakers let the ban expire.

Now, 20 years after the Fairchild shooting, they know what it's like to be forgotten when the next tragedy strikes. Time, they've learned, only heals so much.

JUNE 20, 1994, EARLIER — The hospital pharmacy is packed. The wait is at least 20 minutes, and there are hardly any open seats. But when you make a doctor's appointment at the base, you don't cancel it, so now, on this sweltering Monday afternoon, Melissa Moe's entire family is here in the pharmacy waiting room — Dad, Mom, little sister Kelly, plus the four kids she and Kelly are babysitting for the summer.

Melissa is 15, blonde and typical in the way teenagers long to be. She goes to Shadle Park High School. She's on the drill team. She plays softball and dates boys. Today's the first day of her first "big kid" job — nannying the Zucchetto kids, Janessa and Anthony, ages 5 and 4 — and she's living with their family all summer in Mead. She has brand-new clothes packed in her suitcase at the Zucchettos' place. That morning, she picked out the cutest outfit from the bunch: a white eyelet tank top and pair of jean shorts from the Gap. Minutes ago, she had managed to convince a dermatologist, a short man in a dark exam room, that she didn't need any skin tags removed — at least not today, because she was scared it would hurt.

Pop. Pop.

Melissa has Janessa in her lap and Anthony on the floor the beside her, rolling his favorite toy, a Thomas the Tank Engine train, across her knee. Her father, Dennis Moe, who works in weapons storage at the base, is standing next to her, staring out two sets of glass double doors that lead into the parking lot. When he hears the popping noise, he turns and looks at his family, his face ashen and swept with panic. Twenty years later, it's a look Melissa can't forget.

Pop. Pop.

In the corner of the pharmacy, a man sits on a rubbery, mauve chair facing the wall. A TV mounted above him blasts a cheesy daytime talk show. Melissa had been watching him earlier. She thought he looked peculiar, bobbing his head side to side while he read, oblivious to the traffic in the pharmacy and the volume of the TV. (Only later does she realize he's deaf.) Suddenly, between his legs, the wall explodes. Pieces of splintered glass scatter across the floor.

Her father shouts. "Oh my god — he's got a gun! Everybody run!"

The first shot sounds like a car backfiring. After the second shot, he hears a woman scream.

Stuart Heberlein is in his supervisor's office at the dental clinic, entering data into the computer, scheduling teeth cleanings, root canals and cavities. The door is open. The air conditioning is turned up, but barely working. Heberlein, 24, is the Periodic Dental Exam Program monitor on base. When the intercom announces that a gunman is in the hospital, that Dr. Brigham and Dr. London are down, Heberlein turns to another dental assistant at the clinic. "Grab some oxygen," he says.

Heberlein finds a bag valve mask, and together the two sprint across the parking lot toward the hospital annex, Building 9010, where London and Brigham worked in the Mental Health Unit.

"Get your heads down!" Heberlein's supervisor yells from the door of the dental clinic.

When they arrive, another dentist from the clinic is already in Brigham's office, performing CPR. Brigham is lying on his back on the floor, unconscious, as the dentist applies chest compressions and Heberlein starts mouth-to-mouth.

But nothing's working. Brigham is dying. Heberlein presses his palms into the stricken man's ribs. His chest feels like broken glass.

Save him, Heberlein tells himself. Please save him.

A barrage of 911 and non-emergency calls flood the base's Law Enforcement Desk. The alarm in the emergency room sounds. The phones lines ring simultaneously. The calls come in for hours.

Crime Stop. Reporting a crime or an emergency?

Emergency crime! There's a guy in the hospital running around with a shotgun.

Copy, alright. We're sending somebody over.

Crime Stop. Reporting a crime or an emergency?

Yeah, this is [REDACTED] in housekeeping... Two people got shot in the dining hall in the hospital. One of my housekeepers just notified me.

OK. I'm gonna put you on hold for one second... Holy shit.

It's like a bad dream. You're reaching out, arm stretched as far it'll go, trying desperately to grab hold of someone you love, but your fingertips barely graze hers.

Melissa reaches for Janessa, but in an instant, they're separated. She grabs Anthony, but he's torn from her hands. A stampede of people have taken off through a set of doors and down a hallway on Melissa's left. Some are trampled. Others are left behind.

Melissa spots Janessa in the crowd and pulls her under her arm. They run, but they can't seem to run fast enough. Indistinct screams fade into the chaos. All Melissa can hear are the gunshots reverberating through the hallway, erupting on the walls. She concentrates on the carpet. It's bluish, like a dark bruise. Melissa sees her mother hiding behind a coffee cart, dragging her sister Kelly beside her.

This is an exercise, just a base exercise, she thinks.

They shove through another set of doors. Now green tile covers the floor. They're in the dining hall. Melissa spots 8-year-old Christin McCarron, the little girl her sister is babysitting, and tells her to hide. Christin crawls underneath the dish table.

That's when Melissa turns around. That's when she sees him. For a moment, they're face to face. He's standing with his gun at his hip, 20 feet behind her, aiming right at Janessa.

This isn't a drill. This is real.

As Melissa pushes Janessa away from the gunman's sights, she's struck with a burning pain, unlike anything she's ever felt before. When she looks down, she can see inside her entire leg: muscles, tissue, and bone.

She drags herself across the tile, Janessa still tucked under her arm, and underneath the kitchen sink. Blood pools at her side. Bullets whiz by, chipping away at the ceramic sink. Janessa's sobbing now. "It itches!" she cries. Her neck is red and torn. Melissa tells Janessa that she's been shot. Hold on to the pipe, she says, and squeeze tight. "We're going to play hide-and-seek from the bad guy," Melissa remembers saying. "We're going to stay here and we're going to be as quiet as we possibly can."

Andy Brown hears the radio call shortly after 3 pm, a little more than an hour into his shift. He's 24 and a policeman with the 92nd Air Force Security Police Squadron. Today is his second day on bike patrol. The afternoon is hot; his legs are tired. Moments ago, he arrived at the back-gate shack for some cool air and a bit of rest.

Most days, radio traffic is quiet. On a busier day, he might respond to a drunk driving incident or car accident, break up a bar fight or a domestic dispute, or arrest a shoplifter. When folks leave their keys inside their cars, he picks the locks with a slim jim. He spent the first hour of his shift pedaling through a housing development on base, waving at passersby enjoying a cloudless summer day.

The hospital is about a third of a mile away, down a two-lane asphalt road. Brown pedals hard and fast. Dozens of cars coming from the hospital stream past him. A military dump truck rolls by, filled with people standing in the dump bed and clinging onto the sides. They wave their arms wildly and yell something urgent, but Brown can't hear what they're saying. Time is passing in slow motion and everything is quiet, like swimming underwater through a dense and briny sea.

As he nears the hospital campus, Brown can hear gunshots ricocheting off the sides of the buildings.

"Where is he?" he yells.

Before he entered the military, Brown had never seriously thought about taking a life to defend himself or anyone else. He grew up in an old farmhouse in Port Orchard, Wash., shooting pine cones with a lever-action BB gun, the kind of kid who'd rescue a wayward spider instead of killing it. At Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, he learned to recite the Air Force's Security Police Creed by heart. ("I am a security policeman. I hold allegiance to my country, devotion to duty, and personal integrity above all.") He learned you only use deadly force against a target who's demonstrated an intent to kill.

Up ahead, Brown sees a man in dark clothes walking toward him on the road, a long gun at his hip. The man fires to his left at the hospital, to his right at a row of military houses.

Brown coasts up a sidewalk ramp, jumps off his bike and kneels on the pavement. He draws his sidearm and takes aim with both hands. He has 15 rounds in his gun and another 15 in a spare magazine.

The effective range of his Beretta M9 is just over 50 yards, half the length of a football field, but to hit a target with any accuracy, most troops are trained to shoot from half that distance. He doesn't know it, but Brown is at least 65 yards away.

"Police!" he yells. "Drop your weapon! Put it down!"

A man and woman in military fatigues find Melissa's trail of blood in the kitchen. They cut off her brand-new clothes and carry her out of the dining hall on a stretcher while she watches first responders cover 8-year-old Christin McCarron's body with a sheet.

"Where's my mom? Where's my dad?" Melissa screams. "Where's Anthony?"

They pass her mother in the hallway, lying on her back on the carpet near the coffee stand, her head turned to the side. They're cutting off her clothes, too. "It's gonna be OK, Melissa," she says. "It's gonna be OK."

The man who rescued her tells Melissa to call him "Sergeant T." At first, she had mistaken him for the gunman. When he found her, she kicked him and screamed. Sergeant T has a tan, kind face and large, warm hands. He looks scared, like he wants to cry, but instead he tells Melissa to "squeeze as tight as you want." So she holds his hand going up the elevator and through the hallway and in the patient room, even while she receives a catheter and he stands outside a closed curtain. He feels like home, and she's never felt safer.

"I promise I'm not going to leave until they tell me I have to," she remembers him saying.

Sergeant T has to convince Melissa to pull her other hand out of her leg. She endures the worst pain she's ever felt all over again. He takes her outside where ambulances are waiting. The hospital grounds look like a war scene. White sheets and blood are everywhere. She's scared she might be alone.

Melissa wakes up in Valley Hospital, surrounded by doctors and nurses in masks and gowns. She's in the Intensive Care Unit for three weeks, but she's in and out of doctors' offices for the rest of the summer. When she starts school in the fall, she's the only girl in her class with a colostomy bag tucked into the waistband of her jeans. She's the girl who got shot, who wakes up bawling in the middle of the night and can't sleep alone. Everyone in her family was wounded. These days, it feels like they're barely surviving.

That night, Brown hears the details of the shooting for the first time while watching the 11 o'clock news. He's staying in the guest bedroom at his supervisor's place in a mobile home park off base, and he can't sleep. Every time he closes his eyes, he sees the gunman walking toward him, his body flung backwards and collapsing on the ground. Over and over and over again. So Brown watches each hour of the clock go by. Startled by every noise outside, he climbs out of bed and peeks through the window. He hasn't slept well ever since.

Ten days later, Brown is awarded the Airman's Medal, the Air Force's highest peacetime honor. He's lauded as a hero in newspapers, Rotary Clubs and military bases. But Brown doesn't like the attention. Nor does he care for the praise when innocent people lost their lives that day and dozens of others were hurt.

Brown is different now. He's hyper-alert all the time, anxious and depressed, overwhelmed by crowds and withdrawn. The military offers him counseling, but he declines to go through with it when he realizes he'd have to turn in his weapon. He doesn't want to be relegated to the "rubber gun list" of cops who can't be trusted with their sidearms. So every night, he buys a pack of whatever's cold and cheap, locks all the doors in his home, and numbs his anxiety with a few cans of beer.

Things only get worse for Brown when he's transferred to Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii in 1995. He was told it would be beautiful there, that he could meet a girl, but all Brown sees is crime and crowds. The shooting is always on his mind. The bullet holes in the walls of the hospital. The shell casings on the floor. The metallic smell of blood in the hallways and dining hall. He thinks about the people who died and were wounded while he rushed to the scene. Again, he visits with a counselor. Again, his weapon's pulled and he's relieved of duty. So Brown gets his gun back and quits therapy, and wonders how many lives he could have saved if he just would have arrived a second or two earlier.

At Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico, Brown's temper spirals out of control. He throws chairs in the interrogation room while interviewing suspects; hurls case files; kicks the walls in his office and slams his computer keyboard with his fist.

In 1999, he makes an appointment with a base psychologist and is diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. They meet for several months, but for Brown, it's too late. Nothing seems to be helping. He requests a medical discharge. He wants to go back home.

The Air Force needs dental workers in Europe, so Heberlein volunteers to transfer to Germany. Six weeks later, in March of 1995, he's at Spangdahlem Air Base, inexplicably angry, listless and afraid to fall asleep.

He has variations of the same nightmares almost every night. He dreams of crashing aircraft and smoldering ruins. Sometimes he's in a combat zone with a weapon that can't fire. The enemy approaches — his gun raised — and Heberlein pulls a limp trigger. He wakes up before he's shot.

Heberlein tells his boss something's wrong. He goes to see the psychologist on base who diagnoses Heberlein with PTSD and recommends counseling. But Heberlein doesn't go. He doesn't think he needs it. He thinks he's going to be strong. Therapy is just a bunch of hocus-pocus, anyway.

Four years later, Heberlein is honorably discharged. Two weeks before he leaves Spangdahlem, he walks downstairs from the dental clinic and asks to see his medical records. He flips through his file until he finds the sheet signed by the base psychologist — the one that says he's showing signs of PTSD. Heberlein takes it out, makes a copy and promptly loses them both, so no one will ever know.

Melissa starts seeing her therapist, Jill, shortly after the shooting. One afternoon, when she's 17, they go to Laser Quest downtown together and Jill asks for a private game. "Don't turn on the lights," she tells the employees. "I want it to feel real."

Jill shows her how the vests work, how they vibrate when you're shot. She tells Melissa she's going to shoot her and asks Melissa to shoot her back. But inside the maze, Melissa struggles to breathe. It's dark. Lights are flashing. The air is filled with artificial smoke. Someone could walk around the corner any minute, armed with a real weapon. She drops to her knees in tears.

"That could happen anywhere. Not just here. You know that," Jill says. "You need to trust that I'm not here to hurt you and you're not here to hurt me. That's what we're learning."

The next five minutes feel like five hours, but Melissa plays laser tag with her therapist. A small part of her feels like a kid again.

Two years later, for one of their last sessions, they meet at the hospital parking lot on base. They walk through the pharmacy holding hands. They read a backlit plaque memorializing the dead. Melissa lets her fingers trace the walls.

On June 20, 2001, the seven-year anniversary of the shooting, Melissa's daughter Hailie is born. The doctor tells her she'll never see that day the same way again. "You need to look at this," he says of her baby, "like a blessing from God."

Brown meets a young woman named Rhonda Strong in Spokane. She's 20, a military buddy's niece, sweet, pretty and gentle. She asks Brown out. Three years later, they marry. They have two children. But their household is tense. Brown drinks a lot. He's always on edge. She tells Brown he needs "to crawl out of your hole." So with his wife's encouragement, he tries anything he can to get better — antidepressants, exercise, diet, meditation and acupuncture. But everything just feels like a Band-Aid. Brown figures he's a lost cause.

After 14 years and multiple Freedom of Information Act requests, Brown's persistence finally pays off. He receives a digital copy in the mail of the base's radio transmissions from the day of the shooting. He listens to the tapes and calculates his response time: Less than two minutes. He forgives himself a little for that.

In 2010, Brown enrolls in two new programs offered by Spokane's Department of Veteran Affairs. One is called "cognitive processing therapy." The other is "prolonged exposure therapy." They change the way Brown views other people, their actions and the shooting itself. He no longer feels anxious at the shopping mall. Getting cut off in traffic isn't a personal affront. He learns to be empathetic, to trust others again, to breathe deeply when he's feeling overwhelmed. The world isn't full of assholes, just people, making mistakes and doing the best they can.

Brown is working on a book about the shooting and the gunman's troubled past. He scours stacks of police reports and witness statements. He creates a Facebook page for survivors and interviews dozens of them. He learns that their experiences following the shooting aren't too different from his own. He writes on a laptop at the library, or Petit Chat bakery, or on the weekends at the border patrol office where he works as a dispatcher.

For him, writing the book is a form of immersion therapy. His first chapter begins with a radio call and gunfire. He later writes about his struggles with PTSD. He's not sure if he's found the perfect beginning yet, but he has a happy ending in mind.

"I'll never be the same as I was before the shooting," Brown says. "I'll never be normal like I was before, but I found a new normal and life is a lot more worth living now."

Heberlein doesn't have those nightmares anymore. He used to run a lot. That seemed to help. Mostly he just tries to forget.

He doesn't like to talk about what happened, either — particularly with his three young children. He's not ready, and anyway, they know enough about mass shootings because their schools have to prepare them for one, just in case.

His children's knowledge of the Fairchild shooting is contained on two sheets of cardstock in a scrapbook alongside old photos of his military career. Heberlein's Air Force Achievement Medal — a silver, milk-cap-sized medallion with a gray-and-blue-striped ribbon — is glued inside with a certificate commending his "high degree of courage and professionalism," "heroic effort" and "quick and selfless actions." Heberlein laughs at it now. Everyone serving in the 92nd Medical Group was awarded one, even those who weren't on base that day.

"I just think it's funny," he says. "It's like being on the Oprah show. You get an Achievement Award! You get an Achievement Award!"

Every night, in his home at the end of a cul-de-sac in Veradale, Wash., Heberlein inspects the locks on all the doors. He sleeps lightly and wakes to every creak in the floorboards, every tiny footstep. Usually it's his youngest son, Owen, crawling into bed with Mom and Dad because he had a bad dream.

Heberlein has learned to expect anything at any moment. At the grocery store. At a coffee shop. At the oral surgery office in North Spokane where he works. Every day he wonders: If someone walks in here with a weapon and starts shooting, what am I going to do?

"That's the funny thing about it," he says, cracking an ironic smile. "You don't know when somebody is going to go crazy."

In September of 2009, Melissa marries a man named Bobby. He's a friend of a friend who kept coming around for years, and her girls need a dad. They have a simple church wedding in Spokane Valley. She wears a white strapless dress; he rents a tux. Dinner is served potluck style.

Her father's cancer is in remission, but he's too sick to attend. So minutes before the ceremony, Melissa's maid of honor looks at a photo on Facebook and pulls aside a man from the pew wearing a polo shirt and slacks. Melissa asks him if he'll give her away. It's the first time she's met Andy Brown in person.

"Of course," he says, "but I need a jacket!"

"You're fine," she says. "It's just an honor to have you by my side."

Melissa divorces Bobby less than a year later. She'd been in love with her best friend all along. She met Jessica Cochran, her partner, when they were volunteering for their daughters' parent-teacher organization. There had been whispers about whether they were a couple or not. Now the whispers are true.

Cochran teaches Melissa how to "feel normal" again. "We're not going to use this medicine anymore," she tells her one day. "You don't need this. Let's just try." So Melissa gradually weans herself off the antidepressants and antianxiety pills. Within six months, she can cry when she wants to cry; she can feel when she wants to feel. She's happier now than she's been since she was at least 15 years old. She finally has the family she's always wanted.

Melissa isn't angry at the man with the gun anymore. "He was sick," she says. "He had something wrong inside. Something happened to him that made him do what he did."

But compassion hasn't been easy. Every day, she has to face her forgiveness when she looks at herself in the mirror. She doesn't recognize her body. It's someone else's. Something someone made. A cruel portrait by a twisted artist.

"I'm pieced together. This is what he left," she says. "But I'm still here, and he isn't."

One scar stretches from the bottom of her sternum to her pelvic region. Another meanders down her inner right thigh; a third crosses her knee. A wide stripe of bubbly pink skin trails below her belly button. That's where she was opened up twice for surgery in the year and a half following the shooting. But Cochran reminds Melissa she's beautiful — scars and all. ♦

Remembering Fairchild

Current and retired members of the military are invited to attend a ceremony honoring the victims of the Fairchild Air Force Base shooting this Friday at 3 pm at the base’s Memorial Park. The event will feature remarks from former Staff Sgt. Andy Brown. Interested attendees should call (509) 247-5705 for more information. To learn more about Brown’s forthcoming book on the shooting, Warnings Unheeded, please visit fairchildhospitalshooting.com.