In Spokane County, a single person died of a fentanyl-related overdose in 2018, according to official records.

Each year since, the annual number of casualties in this iteration of the opioid crisis has increased dramatically. By the end of 2023, it hit a devastating new record of 194 people, according to the county medical examiner's latest annual report.

Read that again: Last year, fentanyl killed someone in this community every other day. Every. Other. Day.

What often gets lost, however, is how many people overdose and survive every day in Spokane.

Who is struggling with addiction? Who is working to maintain their sobriety? Who is trying to help a family member get to the point where they're ready to get clean?

Who is offering medical care and the chance to get treatment? Who is trying to stop the deadly supply from winding up on scraps of foil to be smoked?

In the course of a month, how does fentanyl affect our city? Here's a glimpse.

OCT. 1, 6:18 PM'MORE WORK TO DO'

More than 43 million people have tuned into the vice presidential debate, where U.S. Sen. JD Vance of Ohio and Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz are diving into the topic of border security and fentanyl.

Vance reminds viewers that his mother was addicted to opioids and says he wants to stem the flow of synthetic narcotics across the southern border.

Though not mentioned during the debate, earlier in the day Reuters published another story in its "Fentanyl Express" series, detailing how precursor ingredients are shipped by plane in everyday packages from China to the U.S., then delivered by vehicle to Mexico where they're used to make fentanyl that gets smuggled back into the U.S.

"This is a crisis," Walz says. "The good news on this is, the last 12 months saw the largest decrease in opioid deaths in our nation's history. ... But there's still more work to do."

Some watching in Spokane wonder how that can be true.

Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that for the first time in at least a decade, drug overdose deaths have started decreasing nationwide, and were predicted to be down by more than 12% from May 2023 to May 2024.

Unfortunately, that's not the case in Washington, where the CDC expects its data to show overdose deaths — a majority of which involved fentanyl — increased nearly 11% during that same timeframe.

OCT. 2, 3 PM & 5:30 PM'NOBODY DIES TODAY'

It's about 3 pm on the first Wednesday of the month.

Catherine Herrman, who's been a peer support worker with Compassionate Addiction Treatment, or CAT, for a few weeks now heads to the 7-Eleven across the street to grab lunch.

But before heading inside she notices a man slumped over on the ground, starting to fall backwards. She realizes he may be overdosing. After checking his right wrist for a pulse and feeling nothing, she grabs Narcan, or naloxone, from her bag and injects him — if he's not overdosing on an opioid, the medication won't harm him. If he is, it might save his life.

"Immediately we had to start doing CPR. Another guy called 911," Herrman says. "He wasn't responding, so I had to run back to my vehicle to get more Narcan out of the trunk."

She administers two more doses.

"After the third one, I was doing compressions on him when I finally felt a heartbeat, and he looked up at me and sat up," Herrman says. "It took him a little while to come to, and talk to me, but I was able to talk him into going to stabilization."

Just hours later, as she's leaving work around 5:30 pm, a guy runs up, asking if anyone has Narcan. Herrman rushes with him to a parked car, where a security guard from a nearby building is attempting chest compressions on a woman slumped over behind the wheel. Herrman says they need to get the woman down on the ground to do CPR.

We believe in harm reduction, which is why a lot of people don't like us, because we believe in meeting people where they're at.

With Narcan, that woman is also revived. It's the second life Herrman has helped save in one afternoon. They weren't the first, and won't be her last.

"I was a user for many years," she says. "I never overdosed, but I always was saving lives then, and so something just pulls me to it now. No matter what I'm doing, I will stop and I run."

Herrman says that going to prison in May 2022 saved her life. Now, her work with CAT, located near Second and Division, is helping as she studies to become a substance use dependency counselor.

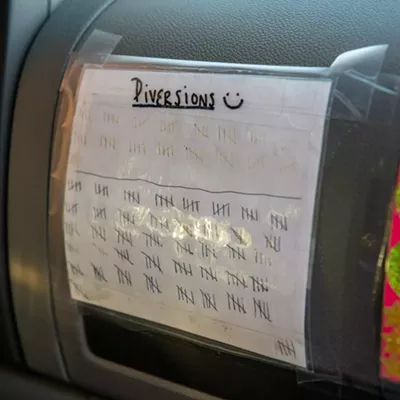

She and Keasha Rosenberg, the medication-assisted treatment clinic supervisor and peer support supervisor for CAT, say they often see more overdoses around the first of the month. That's when many people receive monthly government assistance payments. If they've gone without using for a while, their tolerance drops, making overdose more likely.

CAT works to get people through detox and onto medication-assisted treatment, but the team also tries to make sure people are as safe as they can be if they're going to continue using.

"We believe in harm reduction, which is why a lot of people don't like us, because we believe in meeting people where they're at," Rosenberg says. "We just kind of build your treatment plan on what you want your future and your life to look like."

Nearly dying from an overdose isn't always enough to convince someone to stop. Days after helping the man at 7-Eleven, Herrman sees him on the street. He didn't carry through with treatment.

Herrman says she didn't always agree with the idea of medication-assisted treatment, which is usually either a regimen of Suboxone (a mix of buprenorphine and naloxone) or methadone, both of which bind to receptors in the brain to reduce the physical cravings for opioids, without getting people high like fentanyl does.

"I was really against it before I was a heroin addict," Herrman says.

But being put on Suboxone before she left prison in February 2023 gave her clarity on why it's needed.

"Your brain stops craving it ... and you can actually live a normal life," Herrman says. "It helps me so much with my whole life."

CAT also offers housing and employment services, reentry services for those leaving incarceration, a sobering center, and an intensive outpatient treatment program with group sessions every day.

And, they often respond to overdoses.

"All of us are really strong on, like, 'Nobody dies today,'" Herrman says.

FINAL DOSE

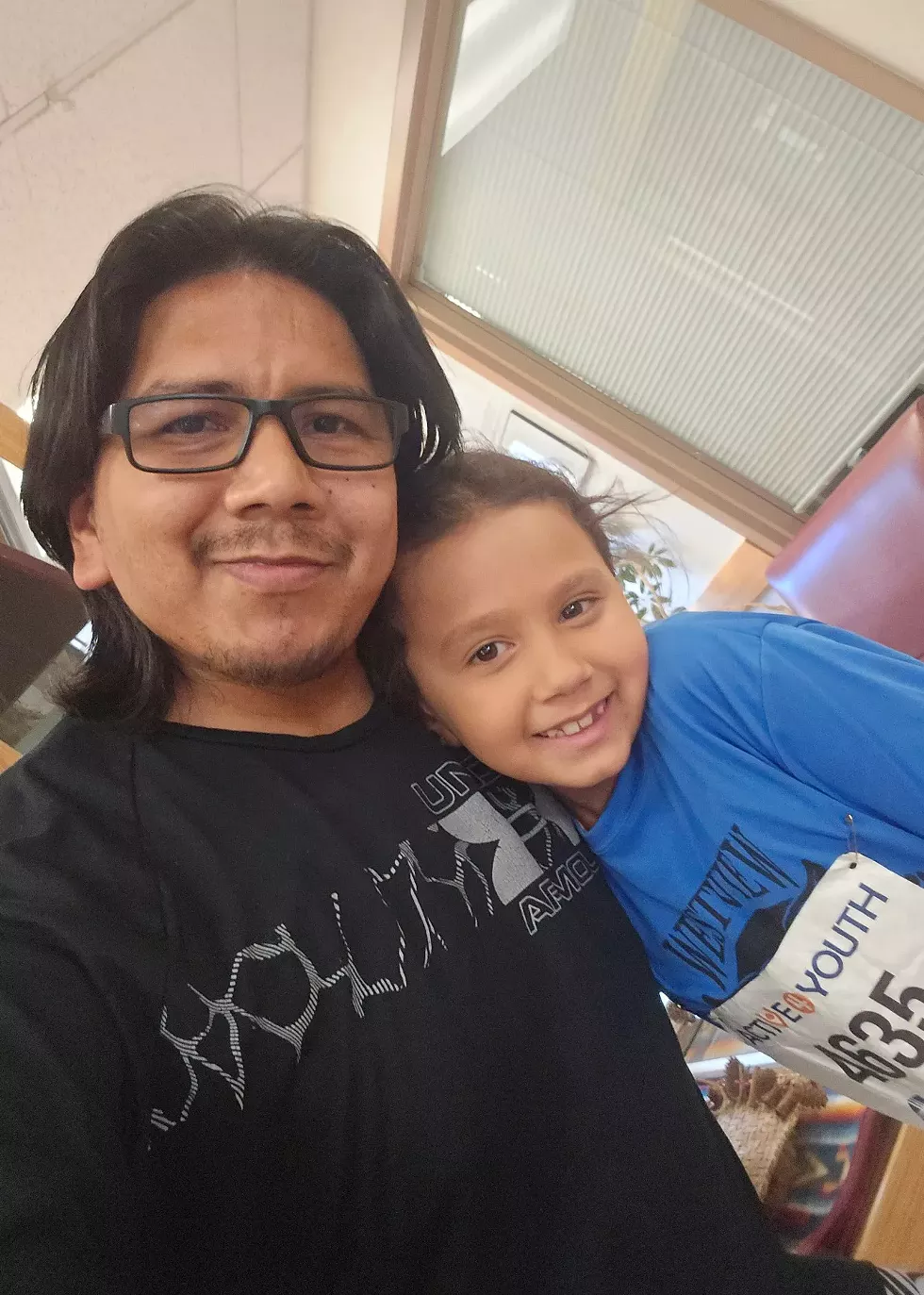

Two-and-a-half years ago, Sean Moses overdosed on fentanyl.

"I lost my dad when I was 13, to a heart attack. That was devastating," Moses says. "When I OD'd and my buddies Narcaned me, my trauma ran back through me and I was like, 'I almost left my kids without a father.'"

Moses decided to get sober. He figured his best shot was to deal with a warrant for his arrest for driving under the influence in Skagit County and go through withdrawal in jail.

"I went through about 16 days of hell withdrawing," Moses says. "I got out, I had a clean slate, and I was like, 'You know what, I need to get my ducks lined up.'"

He cut ties with the people he'd been using heroin and then fentanyl with for more than a decade. Going home to Snoqualmie wasn't going to help, so he decided to come to Spokane, where his three kids and girlfriend were.

"I figured if I spent time with my kids and programmed them into my life, I would have more of a reason to stay sober," Moses says. "It just gave me more willpower being around them."

He became a patient with MultiCare Rockwood's Healthy Behavior and Function Clinic, where he got on medication-assisted treatment.

"Dr. [Lora] Jasman saved my life," Moses says of a popular doctor at the clinic who recently retired. "I've been clean and sober and back in my kids' life."

Now, Moses regularly attends Recovery Café, where he speaks with peers going through similar journeys. He also serves on the Washington Fatherhood Council advocating for healthy family relationships.

Lately, he's been on a once-monthly shot of time-released buprenorphine called Sublocade, and today, he's getting his final shot at the clinic.

"I won't be completely out of the program. They're still going to monitor me until I am completely comfortable not going to see them anymore," Moses says. "[And] I'll have Suboxone on hand if I need it."

I'd rather struggle trying to succeed than struggle trying to find a dope sack. That's just all there is to it.

He speaks openly with his kids, now 3, 4 and 7, about what he's been through. He says he started using heroin after multiple close relatives died within a short window of time and he didn't know how to cope. He wants his kids to know it's OK to talk about their feelings.

Getting sober wasn't easy, but he hopes that anyone who's thinking about it tells themself they're worthy, they're strong enough, and they can do it.

"It's all worth the struggle," Moses says. "I'd rather struggle trying to succeed than struggle trying to find a dope sack. That's just all there is to it."

OCT. 10, 2:49 PM'IT HAS NO AGE'

In the parking lot next to Compassionate Addiction Treatment, people are dropping by a health fair, where local providers like CHAS are offering vaccinations and hepatitis testing.

Standing next to the brick building, his possessions in a wagon nearby, Dennis Richey says he's been "out here" — homeless, using fentanyl — for about 20 months.

"It's horrible. It's killing everybody. And the crazy thing is it has no age," he says. "Daily, somebody's dying."

He says he's personally brought back 18 people, and lost one.

"Losing that one was the hardest thing," Richey says. "That was three months ago."

In his experience, injectable Narcan works better to revive people.

Like many Americans, he says his opioid addiction started with legal prescriptions. After four or five years of doctor-supervised pain management, he was cut off. He turned to the streets to find heroin so he didn't feel sick. Now, it's easier to find fentanyl.

Richey isn't interested in medication-assisted treatment. He's been weaning himself off fentanyl.

"I'm down to about four pills a day," he says. "When I got out here, I was between 50 and 100."

He was originally hoping to be off it by his 55th birthday in September.

What does he wish people understood about what's going on?

"We need better communication with the community," he says. "The city has dehumanized us so much that nobody gives a shit. Nobody cares about us. I've tried to show people that we're not all like that. I go around, I clean the streets, pick stuff up."

OCT. 10, 3:35 PMHIERARCHY

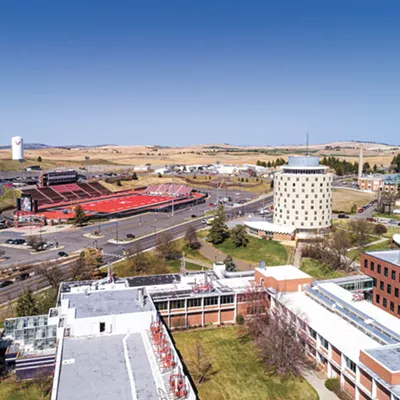

Dr. Joel Edminster is working at his desk at the Spokane Fire Department Training Center near Spokane Community College.

Edminster has been the fire department's medical director for a decade. But his primary gig is working as an emergency room doctor at Providence Sacred Heart.

In addition to an increase in overdoses, he says, the ER is seeing more patients in Narcan-precipitated withdrawal.

The goal of administering naloxone is to restore someone's "respiratory drive," Edminster says.

"That's what kills people in overdose, right? They stop breathing. It's a respiratory depressant," Edminster says. "In a controlled setting like the ER, I typically want to do the lowest dose possible ... ideally you give them just enough to get them breathing again."

But because the opioid crisis has gotten so bad, it's been necessary to get the opiate antidote into the hands of everyday people, and it's a potent dose. Where someone might get 0.4 milligrams of naloxone through an IV in the hospital, he says, they might receive 10 times that amount from a nasal dose in the community.

Sent into immediate withdrawal, those patients arrive dealing with a wave of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bellyache, goosebumps and other debilitating side effects. Some don't stick around the waiting room to get admitted.

"So I go out, I'm dope sick now because I got resuscitated, and instead of being able to have an amount of introspection, recognize that this was a life-threatening event, maybe do something about it," Edminster says, "I'm now focused on, 'I gotta find more fentanyl.'"

As outlined in Maselow's Hierarchy of Needs, the most basic drive people have is to find food and water. But physical addiction can trump that.

"When the bottom of your hierarchy of need is fentanyl, and I put that above food, I put that above water, I put that above shelter, I put that above safety. I put that above all of these other basic needs that individuals have," Edminster says. "Until you address that need, you will make no progress anywhere else in their life, right?"

It's a big part of why the fire department's Behavioral Response Unit is piloting a program to provide Suboxone after someone has been revived with Narcan. For those who consent, the goal is to offer enough immediate relief to think about what just happened — they nearly died — and commit to getting treatment, Edminster says.

Since the pilot started early this year, less than a dozen patients have taken the team up on the offer.

"This may not be the solution we want it to be, right? This may not be the answer," Edminster says. "I think it is a small piece of what needs to be a bigger solution that's multifaceted, addresses all of those different needs and provides the amount of support that this group requires."

After seeing someone overdose repeatedly and refuse treatment, those around them can feel burnout. But the idea that this is a personal choice and they should face the consequences, even if that means death, is a slippery slope, Edminster says.

"What do I say to the diabetic who poorly manages their diabetes? Do they still eat cookies and brownies and they don't exercise and they end up with a diabetic foot ulcer? Well, f— 'em, right? Let their foot rot off, and they can get septic. That's their choice," Edminster says, sarcastically. "Nobody would say that they're OK with that."

Letting someone die won't fix the problem, he says.

"I completely understand the frustration, but I can promise you, if you let that person die, that won't solve the fentanyl crisis."

OCT. 10, 5:51 PMA WOMAN OVERDOSES

The fire department's Behavioral Response Unit has had a quiet afternoon, with no calls for hours.

The two-person team — a paramedic from the fire department and a mental health professional from Frontier Behavioral Health — respond to all psychiatric calls, as well as overdose calls, while they're on duty. The unit operates from 10 am to 8 pm Monday through Thursday.

Currently, paramedic Colin McEntee and licensed mental health counselor Jordan Ellinwood are that team.

While Ellinwood has served on the unit for more than two years, paramedics cycle through. With a lack of volunteers to take the role, paramedics are assigned to the duty for six-month stints.

Just before 6 pm, 911 dispatchers radio to say a woman is overdosing in an apartment downtown.

Within minutes, McEntee and Ellinwood are on scene, taking the elevator upstairs. As they walk down the hall, they can hear a man around the corner up ahead desperately asking, "Is she dead?"

Other medics are already there, several of them crammed into the apartment, where they've taken over CPR from the man, who'd administered Narcan and called 911.

"How are you doing? Are you OK?" Ellinwood asks him, remaining in the hallway. "Did you have to give her CPR?"

The man is distraught. He hasn't given CPR before, he says, shifting his weight from one foot to the other as he stares at the door, ajar.

"Have you dealt with this kind of thing before?"

"I hate this. I hate this drug," he says. "I hate it so much, and I wish it wasn't on the streets here and everyone who sells this shit would be punished."

He steps back inside the apartment to look for his cigarettes and remains inside.

McEntee grabs a device from a gurney in the hall to help clear the woman's airway, which is partially clogged, possibly with vomit.

Finally, the woman loudly gasps back to life. Within seconds, she's stumbling out of the apartment into the hallway.

"I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry," she repeats, no shirt or shoes on, still gulping for air. She's crying and appears to be looking for someone, disoriented.

"You're not in trouble," Ellinwood says.

"Do you want to sit down?" McEntee asks. "Do you want to just talk to us for a minute?"

The other firefighting staff remain inside the apartment, giving the behavioral team a moment to try to talk to her.

But she just keeps saying "I'm sorry" and goes back into the apartment to hug the man who helped her. She won't engage with anyone else, so the medics and firefighters pack up their gear and leave, preparing for the next call.

BRIDGE TO BRUNCH

Hundreds gather for a 5k run/walk and brunch fundraiser to benefit the MultiCare Behavioral Health Network.

MultiCare, the largest provider of behavioral health services in the state, recently announced plans to open an inpatient behavioral health unit at Deaconess Hospital. The state Department of Commerce has provided a $6 million grant toward the effort, which today's fundraiser also benefits.

While the project is still months to years out, the hospital sees patients in its ER every day who are dealing with issues related to fentanyl use.

Stacy Kitchens has worked in the Deaconess ER for 16 years and has been the clinical nurse manager for about two.

"Every single day we take care of patients that are here for drug-related issues, with overdose issues, people that are found unresponsive," Kitchens says.

Even if someone has received Narcan, they need to be monitored, she says, because sometimes the same dose of fentanyl they already survived can affect them again a few hours later.

"Narcan is shorter-acting than some of these opioids, and it can wear off and they're overdosing again," Kitchens says.

Since Washington passed a law to increase access in 2021, emergency departments have also provided patients with opiate use disorder with the overdose reversal medication when they're discharged.

"Anybody who comes in with substance issues, we send them home with Narcan," Kitchens says.

MultiCare is also the latest to sign a contract with Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services, or STARS, to help transfer patients to detox beds downtown.

Sacred Heart also has STARS liaisons in the ER who are able to assess people willing to transfer, get them a bridge prescription for Suboxone and then transport them to detox, Edminster says.

"You never know when that one overdose, and you save that person, that might be the time when they're ready to be done and they might seek sobriety," Kitchens says.

OCT. 15REAL ESTATE PURCHASE

Today is a big day for Maddie's Place, a nonprofit that provides care for babies exposed to drugs while in utero, as well as for their parents. That's because today they closed a $1 million transaction to buy six lots next door to the existing facility on East Eighth Avenue and South Arthur Street.

This month, Maddie's Place celebrated two years since it opened. In that time, the organization has helped 100 babies and 67 parents.

From just mid-September to mid-October, seven infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome were admitted, says Shaun Cross, the president and CEO of Maddie's Place.

The nonprofit closed the real estate deal after receiving $600,000 from Spokane County's opioid settlement funds, the result of lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and pharmacies that contributed to the opioid crisis.

About $400,000 of the opioid settlement money was used for the purchase, Cross says. The organization will spend the next 10 years paying another $600,000 to the property sellers.

The expanded space will allow the nonprofit to build transitional housing for parents and infants who graduate from the facility's care (typically about 60 days) but need more time to find stable housing. Nearly everyone the nonprofit has helped was homeless before they arrived at Maddie's Place.

If demand continues to grow, there will be room to expand. Down the road, the nonprofit could even look for a partner to open a pediatric care facility, Cross says.

The other $200,000 in opioid settlement money is being used to remodel the current Maddie's Place facility to create more office space for its growing staff, currently 79 employees.

Cross, a lawyer, says that based on what he's seen over the last two years, the possibility for parents to keep custody of their child during treatment is a huge factor in successful recovery. Every parent who has lived at the facility is still sober and has custody of the baby that was helped at Maddie's Place, he says.

"If you can provide really complete, total nonjudgmental, loving wraparound support for the parent," Cross says, "it's stunning what the results can be."

OCT. 16, 2:20 PMSHERIFF SHARES HIS FAMILY'S EXPERIENCE

More than 100 people are gathered in the Montvale Event Center on First Avenue downtown for the Spokane Alliance for Fentanyl Education, or S.A.F.E., leadership summit. S.A.F.E. was formed two years ago and regularly hosts events with law enforcement, politicians and young people.

The crowd today includes local politicians, school leaders, law enforcement officers and service providers. At the front of the room, Spokane County Sheriff John Nowels has the mic. He shares that as he was in the middle of running for sheriff in 2022, his own daughter was struggling with fentanyl addiction.

"I want to say that it's unfortunate that I'm the father of an addict," Nowels says. "It's fortunate to say that I'm the father of an addict in recovery."

His third-oldest, Sarah Nowels, started using fentanyl when she was 17. At the time, she was dating a man in his mid-20s. One day, he offered her a pill.

Your daughter's gonna die. You've seen this. It's coming. Will you be able to stand over her grave and say you did everything you could to stop it?

While she thought it might be Percocet (oxycodone), she tells the Inlander that she had an inkling it could be something else.

For three years, the Nowels family went through a cycle. Sarah would live at home, steal money, or continue to use fentanyl with her boyfriend, and get kicked out. Her family wouldn't know how she was doing, so then they'd try to get her home safe again. At one point, her boyfriend overdosed in the then-undersheriff's basement. Sarah's little brother helped perform CPR while the family scrambled to call an ambulance. That was a big moment, Nowels says.

"I told her, 'Hey, you have to choose. You can't use drugs in our home. He can't be here anymore.' I said, 'You are welcome to stay. He is not.' She chose him and left," Nowels tells the audience. "Those are the kinds of things that parents and families who are dealing with addicts have to deal with."

Nowels was elected sheriff in November 2022. Days before Christmas that year, and about a week before he was set to be sworn in, Nowels' family gathered at his father-in-law's home to bake and decorate sugar cookies. Sarah was invited, and when she arrived, her own family barely recognized her, he says. She left soon after.

"As she was walking through the snow, she was shuffling. She's 20 years old at the time, former athlete," Nowels says. "I remember going home that night, not able to sleep ... I just thought to myself, 'You know, your daughter's gonna die. You've seen this. It's coming. Will you be able to stand over her grave and say you did everything you could to stop it?' And I knew I hadn't."

The next morning, he reached out to friends in the behavioral health world for advice. Because Sarah had also struggled with her mental health and had made suicidal comments, the Nowels were able to put her on an involuntary mental health hold and get her admitted at Inland Northwest Behavioral Health hospital.

Sarah says she first started out using around 10 pills a day, initially snorting them, then smoking them. By the time her family put her in the hospital, she was using 100 to 150 pills every day.

"How addiction works is, everything gets put on the back burner, just to use," Sarah says. "There's no logic going on when you're using and you're in active addiction."

In the weeks leading up to her hospitalization, Sarah says she'd hit rock bottom. She was fired from her job. Her relationship with her boyfriend was the worst it had ever been. She had lost a significant amount of weight.

At the hospital, she met a man in recovery who was addicted to heroin for many years.

"He just asked me, like, 'Aren't you tired?'" Sarah says.

She was. So exhausted.

"It doesn't matter what age, race, how you grew up, what class you're in, it touches everybody."

"He just kept saying, 'Is it worth not changing? What's going to be more painful, living like this for the rest of your life, or taking the initiative to change?'" Sarah recalls. "I realized I can't keep doing this. I can't keep going to the hospital. I can't keep being in these types of relationships. I can't keep living this life. And that's kind of when it changed for me."

Nearly two years later, at 22, she now works in peer support for Frontier Behavioral Health.

But Sarah says she wouldn't have been able to get sober without the love and support of her family. She was able to fully focus on her recovery without worrying about getting a job at first. Not everyone is that lucky, and she wishes more people understood that addiction is a disease.

"It doesn't matter what age, race, how you grew up, what class you're in, it touches everybody," she says. "I understand that people are hurt by us, and by the things we do. But I think they also need to recognize that a lot of the time, we're not in the driver's seat of what's going on during that time. It's the addiction that's in control."

OCT. 24, 1:30 PMFEDERAL ANTI-TRAFFICKING BILL

U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell is holding a press conference with Mayor Lisa Brown, Spokane Police Chief Kevin Hall, Sheriff Nowels, and Spokane County Commissioner Mary Kuney in front of Spokane Fire Station 1 on Riverside Avenue to talk about a new bill she recently introduced to stop the flow of fentanyl.

Spokane Fire Station 1 is the busiest in the state, primarily due to the fentanyl crisis, Cantwell says.

"We need to disrupt the supply chain and the financing of drugs," Cantwell says.

The Stop Smuggling Illicit Synthetic Drugs on U.S. Transportation Networks Act would significantly ramp up inspections of all cargo sent by air, sea, rail or vehicle into the country.

It would also authorize federal grants to state, local and tribal law enforcement agencies for new technology, drug-detecting canines and staff overtime, and would increase crime scene and forensics support for fentanyl-related crimes and deaths.

Cantwell and U.S. Sen. Patty Murray are also trying to secure $3 million for the Spokane Regional Crisis Stabilization Center, where police and mental health providers can divert people in crisis, including those with substance use disorder, to get stabilizing treatment.

"It's clear that more people in Spokane could be helped if we add more funding to the regional center," Cantwell says. "These resources are worth fighting for."

FENTANYL ON THE FIELD

At the Spokane Zephyr's last home soccer match of the fall season, thousands of fans at ONE Spokane Stadium offer applause for Stephanie Van Marter, who's being honored on the field.

Van Marter serves on the board of S.A.F.E. and handles criminal prosecutions under U.S. Attorney Vanessa Waldref, who heads up the Eastern District of Washington. The district handles cases in all 20 Eastern Washington counties, with offices in Spokane, Yakima and Richland.

Waldref says attorneys in her office regularly build cases against the largest drug traffickers in our region, which sometimes takes years.

"We have been really making fentanyl cases a critical priority," Waldref says. "We partner with our large federal agencies ... to identify large drug trafficking organizations. We try to infiltrate those organizations [and] go after the largest source."

About five years ago, Eastern Washington started seeing a dramatic increase in fentanyl making its way into the community, most often from Mexico, Waldref says. It often enters the state through the Tri-Cities.

"We started seeing just volumes that were unprecedented, and also seeing with the increase of quantity, the decrease in price of fentanyl pills, fentanyl powder," Waldref says.

Working with the Drug Enforcement Administration, the FBI, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, as well as other local and state law enforcement agencies, Waldref's team figures out which cases are best suited to be prosecuted at the federal level. Often a suspect's violent history might be a factor to try that case in federal court, she says.

Federal cases can result in longer sentences, and the federal prison system is equipped with better rehabilitative programs and reentry services, Waldref says.

Her office also helps obtain warrants to seize large quantities of fentanyl and even pill presses. In January, two men were indicted by a federal grand jury in Spokane after investigators seized two commercial pill presses that could produce thousands of pills per hour.

In a unanimous vote on Sept. 23, the Spokane City Council voted to hire a special assistant U.S. attorney to help prosecute serious drug crimes in the city. The city-employed attorney will work with Waldref's office and will be paid with revenue the city receives from cannabis sales.

Before the vote, Spokane City Council member Jonathan Bingle agreed with a public commenter named Terry, who applauded the move to go after drug dealers.

"Terry said it really well: The more of these dirtbags we can get off the streets, the better," Bingle said. "I think this is a very good action from the Brown administration. ... There's no single greater issue facing the city of Spokane right now than drugs." ♦