On a chilly Saturday morning in late March, Joseph Sampson, 47, was standing with a group of friends across the street from City Gate, a downtown food bank and church for unhoused people on Madison Street. Volunteers had just distributed an Easter meal, and Sampson, who was homeless at the time, was eating from a to-go box while standing on the sidewalk.

A police officer driving by noticed the large group. Over his loudspeaker, he said they were blocking the sidewalk and had to leave immediately or risk being cited for "pedestrian interference."

People started to leave. The officer got out of his car and approached those who remained. The sidewalk was partially obstructed by bikes, an office chair, a cart full of belongings and a man lying down under a blanket. Sampson and three others were still standing and eating food.

"I've given multiple warnings, and we still have people who are hanging out over here, probably doing drugs," the officer said, as captured by body camera footage the Inlander reviewed. "Let's pick it up. Let's go, come on."

Spokane's pedestrian interference law makes it a misdemeanor to "intentionally walk, stand, sit, lie or place an object" in a manner that obstructs pedestrian traffic. The ordinance doesn't always get as much attention as Spokane's other homeless-related laws, but it's a key pillar in how the city enforces where people can and can't be. Citations have spiked in recent months — and Sampson and others in the homeless community say they've noticed the uptick.

On Madison Street, people slowly gathered their belongings. Sampson, sporting a bushy black beard and baseball cap, kept eating. The officer's comment about people doing drugs had bothered him.

"Sorry, I'm just enjoying my drugs over here," Sampson said sarcastically, pointing at his food.

The officer said he was trying to be nice but would have to cite Sampson if he continued to refuse to leave.

"I'm enjoying my breakfast," Sampson said, not moving and continuing to eat.

The officer asked Sampson if he wanted to go to jail, because not following his previous warnings to move along meant he was obstructing. Sampson demurred. "What is it that I'm obstructing?" he said. "I'm just curious."

The officer sighed and started putting on medical gloves. "I don't know why it has to be so difficult," he said.

"I don't know why either," Sampson replied.

Sampson closed his food container and set it down, and the officer moved in and placed him under arrest.

STANDING ON SIDEWALKS

Pedestrian interference is similar to the city's "sit-lie" law, which prohibits sitting or lying down on downtown sidewalks during certain hours. But pedestrian interference is more flexible — with fewer legal constraints.

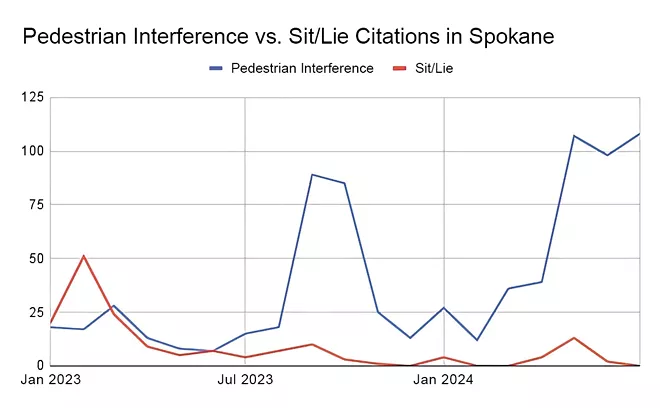

Police data recently obtained by the Inlander shows that, while sit-lie citations have declined compared to last year, pedestrian interference citations have soared.

The vast majority of this year's pedestrian interference citations (so far) were issued over the past three months. In May, June and July, police issued 313 pedestrian interference citations — almost as many as they issued in all of 2023. In comparison, police issued just 15 sit-lie citations in the same time period this year.

The sudden spike appears to be tied to increased downtown police activity for the Expo '74 50th anniversary celebrations, as well as legal uncertainty over other anti-homeless laws like Proposition 1, the initiative that nearly 75% of voters passed in November to massively expand the city's unauthorized camping law.

"Pedestrian interference kind of took over during that time when we were waiting for Prop. 1 to be cleared up for the courts," says Julie Humphreys, a spokesperson for Spokane Police Department.

Some homeless advocates say they're concerned with how pedestrian interference is used. The law is overly broad, they say, and can be unfairly used to target people experiencing homelessness.

Humphreys disagrees. The law's lack of restrictions gives officers more flexibility, she says, and it can be a valuable tool to keep sidewalks safe for pedestrians.

"We have a lot of people that are blocking areas, they might not be camping, but they might have a shopping cart full of all kinds of their belongings," Humphreys says. "We do get regular complaints that people can't pass by."

A misdemeanor is punishable by up to 90 days in jail and a $1,000 fine. But unless people have active warrants or are engaging in other criminal activity, Humphreys says pedestrian interference citations result in a referral to community court, where people can ideally be connected with support services to avoid fines or jail time.

Spokane City Council member Paul Dillon, who chairs the city's public safety committee, says some pedestrian interference citations are warranted. But he's concerned there seems to be a "degree of subjectivity" in how the law is enforced. He's also worried it has "supplanted" sit-lie law in recent months.

"I need to dig in further," he says. "I'm concerned with some of the stories I've heard."

"A CONVENIENT WORKAROUND"

In the body camera video, the officer who arrested Sampson said pedestrian interference is "essentially the same thing" as sit-lie, just with "a little bit different stipulations."

Spokane's sit-lie law applies only to sitting and lying down on sidewalks, but pedestrian interference also covers walking, standing or placing an object in an obstructive manner. It also prohibits aggressive panhandling and interfering with vehicle traffic.

Sit-lie applies only to downtown sidewalks, and can only be enforced between 6 am and midnight when the city has available shelter space. The pedestrian interference law, however, applies citywide, can be enforced 24/7 and has no shelter space restriction.

"It is easier for officers to enforce," Humphreys says. "We can take action on pedestrian interference without having to look for required shelter space."

Jazmyn Clark, a policy program director with the ACLU of Washington, spent more than six years as a public defender in Spokane and says she frequently encountered pedestrian interference cases. She says the law's vagueness can lead to "selective enforcement." The law technically applies to everyone, but it's overwhelmingly used against homeless people, she says.

"It's a real issue, particularly when it is enforced in lieu of anti-camping or sit-lie," Clark says. "Because it doesn't have the same time and place parameters as sit-and-lie, it can be used more broadly... I think that it can be a very convenient workaround for law enforcement."

Humphreys doesn't like the term "selective enforcement."

"Officers always have latitude in enforcing anything, that's the same with a traffic infraction," Humphreys says. "Officers have the leeway to issue a warning or to give someone the citation... There's a lot of education that goes into this. I don't think that equates to selective enforcement."

Last week, the ACLU of Washington filed a major lawsuit against Spokane, alleging that three of the city's anti-homeless laws violate the state constitution's protections of due process and from cruel punishment.

The lawsuit takes issue with the city's sit-lie law; its "unauthorized camping" law, which makes it a misdemeanor to camp in certain places; and another rule that gives the city authority to remove people's belongings while clearing camps.

The laws "criminalize the very existence" of Spokane's unhoused residents, the ACLU lawyers wrote.

Other than one brief footnote, however, pedestrian interference isn't mentioned in the lawsuit. Clark says the ACLU is aware of the law and has concerns about how it is used. When asked why it wasn't included in the lawsuit, she says it was simply a matter of capacity.

"Spokane has a lot of problematic laws," Clark says. "We cannot tackle all of Spokane's problematic ordinances in one go."

EXPO '74

Enforcement of pedestrian interference appears to come in bursts.

The last time citations spiked was in September 2023. As pressure over downtown safety issues loomed, then-Mayor Nadine Woodward held a news conference near the troubled intersection of Second Avenue and Division Street and announced that she was "resetting expectations" and increasing overtime police patrols in the area, which has long struggled with drugs and crime.

Earlier that year, police had averaged about 15 pedestrian interference citations per month. But as officers moved in on Second and Division, the numbers increased sixfold — to 89 in September and 85 in October. Humphreys says the spike was a direct result of the emphasis on the area.

The overtime patrols eased in November (the same month as the mayoral election), and the number of pedestrian interference citations dropped. Lisa Brown was sworn in as mayor in January, and throughout the first few months of 2024, the number of monthly pedestrian interference citations remained low.

In spring, the numbers started to climb again. On March 29, one day before Sampson's arrest, Brown told the Inlander that the city was stepping up law enforcement activity downtown and adding bike patrols ahead of the nine-week Expo anniversary celebrations set to begin on May 4.

Citations skyrocketed as spring turned to summer, surpassing the totals from the prior crackdown on Second and Division: There were 107 in May, 98 in June and 108 in July.

"That is in good part because we had more officers in the downtown area," Humphreys says. "We increased our staffing, we moved officers from other units to the downtown area for the Expo celebration."

LEGAL LIMBO

The extra officers stationed downtown for Expo were pulled back in July. But it wasn't just Expo that caused the spike. Humphreys says legal uncertainty from a pending U.S. Supreme Court decision also played a role.

In late spring and early summer, the city was waiting for the Supreme Court to rule in Grants Pass v. Johnson, an appeal of a 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision that upheld precedent preventing cities from enforcing camping bans without sufficient shelter space, on the basis that it is unconstitutionally cruel and unusual punishment. The shelter bed requirement has limited Spokane's ability to enforce sit-lie and unlawful camping laws.

The looming legal questions also cast uncertainty on Proposition 1, the November ballot initiative that expanded the city's camping ban to cover about 60% of the land within city limits. At the start of this year, the city's legal department advised police to hold off on enforcing it until they could get clarity from the Supreme Court.

Police instead leaned on the pedestrian interference law. It was a "tool we could use at that time," Humphreys says.

At the end of June, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 to reverse the Grants Pass precedent — giving cities across the country broad flexibility to crack down on camping. Pedestrian interference citations remained high in July, in part, Humphreys says, because it took about a month to get the code into the system and to implement mapping technology needed to enforce Prop. 1.

As of last week, Humphreys says, police are now ready and starting to enforce Prop. 1. In response to the Supreme Court's decision, City Council member Jonathan Bingle has proposed extending the sit-lie law to the whole city and removing the shelter space requirement.

Clark, with the ACLU, doesn't think the Supreme Court ruling will impact her organization's lawsuit against Spokane. The ACLU has been building the case for more than a year, and its main legal argument is based on the state constitution, not the federal one.

After being cited with pedestrian interference on March 30, Sampson was given a referral to community court. He tells the Inlander that he asked for the charge to be transferred to municipal court because he wanted to argue his case. He says the prosecutor's office ended up dismissing the charge.

Sampson says he's planning to file a complaint with the Police Ombudsman's Office. He feels that he was unfairly singled out because he spoke up about the comment the officer made about people doing drugs.

On April 17, Sampson signed a lease for an apartment. He'd been trying to find housing for a while, and he's glad the arrest didn't end up jeopardizing that.

Sampson remains housed. He plans to return to Spokane Community College this fall to study to become a paralegal. ♦