There are many stories within the story of Expo '74 — some of conflict and some of cooperation, all driving toward making Spokane the smallest city on earth ever to host a world fair. Success was by no means certain.

Bill Youngs first published The Fair and the Falls in 1996, and it quickly became a must-have on the bookshelf for anyone interested in Expo '74 or the history of Spokane itself. It also quickly went out of print and was available only to those willing to engage with Ebay or a rare book collector. Now, just in time for this year's Expo 50th festivities, Youngs has republished the book. And he has allowed us to excerpt two sections, both from Chapter 14, "Building the Fair." The first looks at what it took to change an industrial landscape into a jewel of an urban park, all the while preserving a bit of the past. The second goes deep into one local professor's work to bring the Ford Pavilion to reality.

As King Cole, president of Expo, remembered: "We not only had some impossible tasks, but we had some impossible timetables."

Two such challenges in the months leading up to the fair's opening day were deciding what to do with the historic railway terminals on the exposition grounds — and furnishing the many exhibits on the fair site, including the Ford Pavilion's waterfall, stream, mountain and tents that touched on the theme of camping.

TEARING DOWN

The first step in building up the new park by the falls was to reduce millions of pounds of iron, wood, stone, and glass to rubble. Some of the rubble could be reused: tens of thousands of bricks and hundreds of tons of iron. Some became fill for the park itself, and some was trucked away to dump sites outside of Spokane. The demolition began on June 1, 1972. "They set it up for a little ceremony beneath the trestles," Mayor David Rodgers recalled. The first target was a row of sheds. The mayor and Bill Quinn, a railroad executive, pulled on a line rigged to a wall, and it tumbled over. A wrecking ball then began pummeling the buildings, and bulldozers scraped up the rubble. The ceremony had one hitch: after a few successful whacks, the wrecking ball fell off its line with a loud "plunk." Despite that accident, the mood was cheerful. "It was a kick-off, getting rid of all of that industrial clutter that was down there. And that was what the city was really trying to do."

During the subsequent months the wreckers tore down the Union Pacific trestles, the railroad tracks on Havermale Island, a Travelodge Motel, an asphalt plant, a crematory, the industrial laundry on Canada Island, old buildings on Skid Road (a blighted part of town on what is now Spokane Falls Boulevard), three railroad bridges over the river, old warehouses, and two Spokane landmarks: the Union Pacific and Great Northern depots. In November 1972, Jack Roberts, a reporter for the Spokesman-Review described the site: "Havermale Island's sinking skyline, slammed for weeks by wrecking balls, is taking on the tired, desolate look of a bomb-gutted section of World War II London. The island, which is the heart of the 100-acre Expo site, is a mass of twisted structural steel, broken chunks of concrete, railroad gondola cars being loaded with salvage, huge cranes poking skyward and piles of nondescript debris."

During the spring of 1973, one year before opening day, new forms began to emerge on the islands and the riverbanks. Graders recontoured the land, and foundations were laid for the opera house, the United States Pavilion, and other structures that would make up the world's fair. One historic landmark by the falls, an old mill, survived the changes of the Expo era. The building was transformed into modern offices, restaurants, and shops. The "Flour Mill," as it was known, was the lone survivor of the many mills that had once flanked the river. The railroad stations met another fate.

Although most citizens were enthusiastic about the new park, many regretted the loss of the depots. They formed an organization called SOS, Save Our Stations, and worked towards retaining at least one as a railroad museum. A debate over the fate of the stations raged in Spokane's newspapers and in letters to the Expo board. Nineteen members of the Spokane Fine Arts Council wrote a letter to Expo's president, King Cole, with copies to city officials, urging the preservation of the Union Pacific Depot; they used the well-worn arguments of environmentalism in defense of the station:

The creative efforts of an earlier generation which provided the craftsmen and building materials to construct this fine old building should not be wasted by the expedient acts of a later generation who would destroy this structure in the name of "Ecology." It is the responsibility of the city of Spokane and the Expo planners to resist the temporary shortcut by removing an "old" building to provide a site for temporary "low cost" exhibition space.

It is the planner's challenge to be creative enough to incorporate the old with the new — it has been successfully executed in many large and small-scale architectural projects .... Recycle the existing building to provide a cultural center for the visual arts and crafts.

King Cole, Expo's architect Tom Adkison, and the city were bombarded with letters proposing various uses for the stations. The Inland Empire Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society argued that "at least one of the depot structures within the Expo '74 site should be preserved and restored to commemorate Spokane's railroad heritage." The chair of a local group called Citizens Against Residential Freeways suggested that the Union Station should be converted into a bus depot. Gerald J. Quinn, who chaired the Save Our Stations committee and attempted to get the issue on the ballot, emphasized the "aesthetic and cultural values connected with the two buildings."

For more than a year after planning began for Expo, the fate of the stations was undetermined. Early site maps and models included both depots. On May 26, 1971, Cliff Warden, assistant director for the fair, wrote to a preservationist: "We are asking that this landmark be retained if possible." On Jan. 26, 1972, King Cole wrote, "considerable time and effort has been spent by the city and Expo on seeking ways to retain classic old structures." Preservationists drafted applications to include the depots on the National Register of Historic Places. The Union Pacific Depot was the only major station in the region "constructed in the Grand Union Terminal motif" and was the location where a golden spike ceremony had taken place, on Sept. 15, 1914. The Great Northern Depot was described as "one of the finest examples of railroad architecture in the United States." Noting the relationship between the two terminals on opposite sides of the river's south channel, the preservationists ventured a comparison to Venice. "The two [depots], when viewed together, form a scene reminiscent of the Piazza del Duomo in Italy, except for the substitution of a reflecting river pool in place of the paved court." They particularly praised the Great Northern tower:

The clock tower gracing the structure is perhaps the most distinguished feature of the building. Rising over 155 feet above ground level, the tower is an established member of the Spokane skyline. .... The nine-foot-diameter clock-faces make it the largest timepiece in the Pacific Northwest. The glass dials total over 1,400 pounds. The zinc pendulum rod weighs nearly 500 pounds and is 8-1/2 feet in length. The total weight comes to 7,050 pounds for the entire piece. The clock was placed in service at high noon on June 20, 1902.

Despite such praise, many Spokanites found little to admire in the buildings. The two professional historians on the committee that had drawn up the National Register nomination ultimately voted against retaining the stations. One of them, Albert Culverwell, the director of Cheney Cowles Museum, wrote Tom Adkison explaining his reservations about depot preservation. He thought that the river itself was important "esthetically and historically." The falls "attracted our first people here and caused them to remain. The railroads came afterward and brought about an increase in our population. It is very important, however, that we recognize what caused our first people to settle here." In losing the depots, the city would gain fuller access to its essential resource, the river.

Others questioned whether the depots were, in fact, notable historical buildings. In the letters to the editor section of the Spokesman-Review, one correspondent noted that the city actually had three old railroad depots, so they could easily afford to tear down the two by the river. The old Northern Pacific terminal, several blocks south, would be sufficient. Moreover, it was the oldest of the three stations anyway, having been built in 1891. Other writers questioned the aesthetic value of the Great Northern Station. "That is an ugly building. If it were of an earlier, particularly beautiful period, I could understand trying to keep it, but it is not!" One writer spoofed the Save Our Stations movement by claiming to have founded an organization dedicated to saving the industrial laundry on Canada Island. "Think what it would have been like," he argued, "not to have had plenty of clean towels in the early mining camps!" He reported that his group, SOL (for Save Our Laundry) was planning to join with a like-minded group called KOFF, Keep Our Falls Foamy. Mimicking a line from Oliver Wendell Holmes's poem, "Old Ironsides," the writer proclaimed: "Arise, oh, clean-minded citizenry! Don't tear our tattered enzymes down!" In local folklore, SOL became Save Our Industrial Laundry, or SOIL, adding to the spoof on SOS.

In the face of substantial opposition, the Save Our Stations movement placed two depot preservation measures on the ballot for the fall of 1972 and blanketed the city with pro-depot signs. The voters were asked to preserve the stations and to adopt a $1.491 million tax levy to restore and maintain the buildings. A few years later, when historical preservation enjoyed greater support in Spokane and around the United States, the measures might have passed. But in 1972, the year of the wrecking ball, the urge to remove the buildings that "encrusted the ecological heart" of the city — in Tom Foley's phrase — was as formidable as the desire had been a century before to harness the falls with mills, bridges, and railroads. The Save Our Stations campaign was hampered by Spokane's traditional suspicion of new taxes, and it also ran counter to the city's newfound commitment to building a park by the river.

The depot ballot measure resulted in a resounding defeat for the preservationists. The voters turned down the proposal to save the stations by a three-to-one margin, and they defeated the levy measure to support preservation by six-to-one. As a concession to history, the fair builders decided, however, to retain the old Great Northern clock tower. Vern Johnson recalled that the "railroad buffs" were at him constantly and he felt that something had to be retained.

Finally I got tired of it, and I said, "I think that I can get you the tower on that Great Northern Station down there, but I can't get you another damn thing." And so I went to the board the next time I got the chance, and I said, "I've just got to get rid of these guys. They're taking all my time, and I promised them that I could give them the tower off of the Great Northern Railroad station."

Rod Lindsay said, "Can you do that? Will it stand up?"

And I said, "Sure it will stand up. It's got a good foundation on it."

"Well," he said. "Let's do it."

The city retained the tower and fixed the clock so that, for the first time in years, it worked. But that was cold comfort to the preservationists. When he heard about the plan to save only the tower, John D. Konen, local secretary of the National Railroad Historical Society complained, "We contend that the tower configuration would have the stigma of a tombstone rather than a monument. Frankly, we would rather see the whole structure demolished than allow the Great Northern tower to taunt the heritage of this fine city." Possibly the most poignant of all the protests against destroying the stations came from Ben Harney, an accountant who had served as treasurer of Save Our Stations. He wrote Mayor Rodgers, telling him that he had supported Expo '74 from the beginning and had even signed a note promising to help underwrite any losses from the fair. Additionally, he said, "For the first time in my life, I sat on my hands while the city passed a B & O tax," funding the fair. On June 23, 1972, when he wrote his letter, the demolition of the trestles nearby had already damaged the station.

A few minutes ago, I drove past the Union Station, and noticed a hole in the corner of the building where demolition had begun. Until now, I don't believe I really accepted the fact that Expo '74 would actually go through with the destruction of these fine old buildings. I am now ashamed that I did not actively oppose Expo '74 from the beginning. Among those of us with a feeling for Spokane's history, this act of vandalism will create a reservoir of bitterness and resentment that will last long after Expo '74 has come and gone.

If Expo '74 had been held 10 or 15 years later, history would have presented more examples of depot preservation. But Spokane's architectural preservationists of 1972 were defeated by an aesthetic which placed a premium on nature. Eventually grass would grow where the stations stood. The six-to-one vote against funding the restoration of the stations was, in part, a measure of public support for the park by the falls. The wide difference in funding for the two movements was another sign of the times. Donations of $5,000 and $10,000 were common for the exposition, while typical donations to Save Our Stations were between $2 and $10.

In 1883 Spokane had greeted the arrival of its first trains with joy. In 1972 the demolition of the structures that separated the city from the river was just as inspiring. The Union Pacific trestles — the infamous "Chinese Wall" — were removed with almost no regrets. Many years later, King Cole described his "defining moment" during the construction. One day he drove down Grand Boulevard from Spokane's South Hill and curved around Sacred Heart Hospital to Washington Street. "There had always been these railroad tracks cutting me off from the view of the north side of town and of the river and everything else. The day that I actually drove down, and they weren't there, I felt like, if nothing happens, if the fair didn't happen, if I died, whatever happened, what I really wanted to do the most of all was to get rid of those damn tracks."

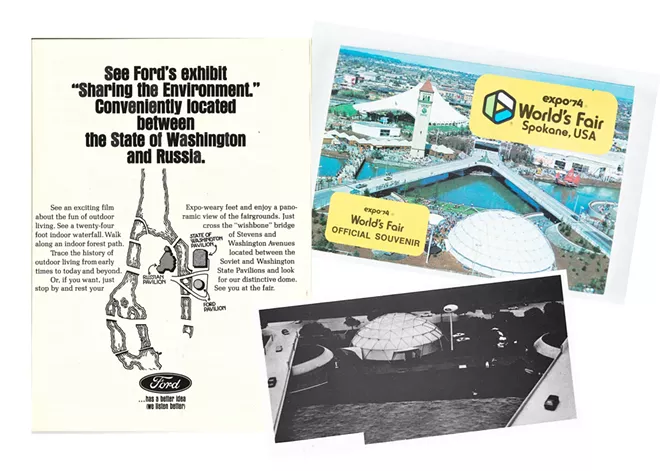

THE FORD PAVILION

Bob Carriker sits in his office at Gonzaga University, reminiscing about his experiences as a staff member at Expo '74. Shortly before the fair, Carriker took a leave of absence from his position in the History Department at Gonzaga to serve as assistant manager of the Ford Pavilion. He remembers those days with a fondness bordering on regret. During his months in a position that involved both public relations and management, he glimpsed another world, far different than the day-to-day life of an academic."I loved that job," he says. "I was in this thing up to my armpits, and it was great. It was a terrific opportunity for me to do something real." Carriker's feelings are a measure of the power Expo '74 had to attract citizens of various backgrounds. Here was a chance to be part of a world-class event. Carriker's Expo experience illustrates that attraction, and his memories of people he worked with along the way illustrate the energizing power of the exposition.

When Ford announced that it was planning to exhibit at Expo '74, the company sent representatives to Spokane to begin planning their pavilion. They contacted Bob Witter, the 17-year-old high school student who had been pestering them for employment, and they promised him a job. Bob Carriker, another Ford admirer, contacted the company's agents in Spokane and arranged a meeting. Taking a line from the popular musical, The Music Man, Carriker told Ford they should hire him because he "knew the territory."

Carriker's interest in working on a pavilion at Expo '74 began with his recognition of the potential impact of the fair on the city. He considered Trent Avenue, Skid Road, and the trestles "a dull, disgusting" part of downtown Spokane. Trent was "really industrial and ugly. There were derelicts on the street. There were shops that catered to derelicts. The parking underneath the tracks reminded you of Chicago." Carriker remembered his first impression when he learned that Expo would change the face of Spokane. "When they put it in the paper, when they drew little white lines around the photographs of the city and said, 'This is going to change; this is going to be an Expo grounds,' I couldn't conceive that all of that building and mortar and brick and steel was going to come down. It was like a dream come true."

Carriker persuaded Ford to hire him as their local contact in the planning stages of the fair. The actual design work and much of the construction for the exposition took place back in Michigan. At first Carriker worked for Exhibit Design Company, which often developed shows for Ford. They came up with the basic exhibit and called on Carriker to help flesh out the details. Later he would help manage the pavilion.

The basic plan called for a display on the theme of camping. The elements of the exhibit would include a stream, a mountain, a waterfall, and various kinds of tents and camping gear — all assembled under a large dome. The pavilion would be erected on grounds that had seen artificial rivers and waterfalls earlier, during the Sportsmen's Shows. The "mountain," 22 feet high, was built in Wayne, Michigan, near Ford headquarters. Most of the tents were high-tech shelters borrowed from a sporting goods company in New York City. And to add a touch of Ford history, the company planned to send Henry Ford's own station wagon, a classic "woody," to Spokane along with a videotape and a display of Henry Ford camping.

The Exhibit Design Company assigned Bob Carriker to handle some of the more challenging details of the project. They wanted a genuine Conestoga wagon, a genuine Indian teepee, and a good facsimile of an Indian horse. Carriker was assistant director of the Museum of Native American Culture in Spokane as well as a professor at Gonzaga. Through his contacts, he was able to track down and borrow a buffalo-skin teepee from an Indian woman in Oregon, and a Conestoga wagon from a museum in Yakima.

The horse was more elusive, but Carriker spotted a likely candidate one day while driving past a saddle shop on Sprague Avenue in Spokane. There he saw a horse made of plaster-of-Paris, and "it had deteriorated quite a bit." Carriker thought it would be perfect, however, for "the Indian motif." Ford had given him a generous allowance for acquiring the necessary artifacts to complete the exhibit, and so Carriker was in a position to buy the horse and pay for its restoration. He trucked it off to an artist who thought he would improve the horse by coating it in epoxy. But the artist lost confidence in his ability to do the job, and passed the commission on to another artist, who also grew faint of heart. "Now I've got this horse, and I've got a place for it," Carriker recalled, "but I've got nobody that can paint it so it won't look like a nag."

In Carriker's estimation, the solution provided an example of the way that ordinary men and women discovered untapped resources in themselves when faced with challenges provided by the world's fair.

My neighbor is a welder, the head of maintenance for School District #81, and he can do anything. I mean, he can build cars. He can build houses. He can repair anything. He can weld anything. He can weld underwater. He can weld standing on his head, and now he showed he could mix epoxy.

He epoxied the horse into a permanent finish. And then I went to the library and got books on Appaloosa horses. We picked out one we liked as a model, and he actually airbrush-painted the horse, and it was perfect. It was widely referred to as one of the best models ever of an Appaloosa horse, and it was made in the garage of the man who was a welder. That's the sort of thing where the people of Spokane had resources and talents they didn't know they had until all of these companies came in town and gave them a chance to show it.

The tent brought a different kind of challenge. The hides were available, but Carriker needed poles. He came to realize that "lodgepole pine" was more than a picturesque name. Carriker spotted a likely grove of trees outside of Spokane and asked the landowner if he could cut about fifteen lodgepoles. He offered to pay, but on hearing that the trees would be used at Expo, the owner insisted that Carriker take them free of charge. "This was something he could do to contribute. Now he could bring his grandchildren to the Ford Motor Company exhibit, and there's a little bit of him and his land inside that exhibit. People in the area loved it, and I was the recipient of that love — I mean, just like the welder who put together a horse, this was a guy who wanted to contribute."

Carriker also needed wood for fencing the pathway inside the Ford Pavilion. The company that made the rails insisted on giving them to Carriker, since they were going to be used for Spokane's exposition.

Meanwhile the design company had completed its work and shipped the Ford exhibit to Spokane in an 18-wheel truck, accompanied by four employees to help set it up. Carriker went one Sunday with his wife and children to a restaurant called Faddy's on Trent Avenue, where he liked to have an omelet and watch the work on the fairgrounds across the street. "One day I went to breakfast, and suddenly there was a geodesic dome where there hadn't been one before. The Exhibit Design Company had come into town and put up the Ford dome."

Carriker enjoyed working with the four Italian-American craftsmen who had come along to set up the exhibit. They treated him to good meals, and they knew their job. The one bad moment came when they took their 18-wheeler to Yakima to pick up the Conestoga wagon. The truck was barreling along the highway back to Spokane with the wagon inside when a police car pulled it over. The officer was apparently one of few people in the Inland Northwest who was not imbued with the spirit of Expo. He gave the driver a ticket for transporting goods within Washington state without a special license.

Inside the Ford Pavilion, the men from Michigan did most of the work. They installed seating and a projection booth for a small theater. They dug a channel through the asphalt floor of the pavilion and coated it with epoxy-like a horizontal water slide to accommodate the stream that would circulate through the pavilion. They set up the man-made mountain from Michigan, and attached a pump. Finding that the pump was too noisy, they expertly packed it in sand so it worked quietly. With their work completed, the men left for home, returning again just before opening day to run final tests.

In the meantime, Bob Carriker made an additional contribution to the exposition. There was an Indian artist in Kalispell, Montana, whom Carriker knew from his appearances at western art shows in Spokane. He had once given one of the Carriker children a picture painted on a rabbit skin. Could he raise a teepee in the traditional native way? The Indian said he could and agreed to drive to Spokane to help out. He let Carriker pay for his transportation, but refused any other payment.

He and Carriker went to the Ford Pavilion one evening after the workers had left. They were joined by a Jesuit priest from Gonzaga. The interior of the pavilion was not yet illuminated. "We had to hook up all kinds of extension cords and then lights and lay them on the ground. It had an eerie feeling." With the Indian's guidance, the men carefully raised the teepee. Carriker explained, "There are spiritual connotations in the direction that you set this up and the order in which the pieces go up."

Soon the job was done; the tent was standing erect, and another milepost was passed in the building of the fair. A genuine teepee — held up by genuine lodge pole pines and raised in a traditional ceremony — stood beside an epoxied horse near an epoxied stream, under a man-made dome in a corporate pavilion. All in all, it was an apt symbol for the diverse forces then at work building a world's fair in Spokane. ♦