Names are everything and everywhere (all at once). We name our children and our pets. We give them to our cars and plush toys, or other inanimate objects. And we give them to places.

On the most basic level, they act as identifiers. But dive deeper into the names of places and you'll find rich histories that are easy to overlook. That's why we wanted to take a deeper look at namesakes within one of the state's largest school districts: Spokane Public Schools.

"We generally name things to honor people," local historian Larry Cebula says. "And the people we name schools after are held up as moral examples to children."

That's why we have schools named for civil rights advocates, educators and even politicians. However, there are many examples of namesakes who weren't exactly moral. One figure Cebula points to locally is James Glover, who Glover Middle School is named for.

Glover was an early pioneer and founder of Spokane. As historians looked into his past though, they found examples of misdeeds against his first wife and the Indigenous communities that called the Inland Northwest home long before any white man claimed ownership of the land.

"The first generation of school names were local settlers who seemed worthy at the time," Cebula says. "There hasn't really been change in how we name things, but our view of settlement and settler colonialism is less romantic these days. We're trying to move away from that."

Though Cebula says our relationship with harmful namesakes has clearly soured over time, the act of renaming places isn't novel.

"The renaming of things is nothing radical or new," he says. "This nation began by pulling down statues of the monarch to rebel against the British."

It's not new to Spokane Public Schools either, which has named and renamed many schools over the years. One of the most recent examples is when the district renamed Sheridan Elementary School in 2021, because its namesake, Union Gen. Philip Sheridan, treated Indigenous communities brutally during the Indian Wars after the Civil War. The school is now named Frances Scott Elementary, after the first Black female lawyer in Spokane.

In total, the district has named five schools in the last three years, three of which were new middle schools paid for with part of the $495 million construction bond voters passed in 2018. School Board President Nikki Otero Lockwood says in that time, it's been important for her to make sure folks from marginalized communities are being recognized for their contributions to the region.

While one could argue that the lack of school namesakes who are people of color reflects a relative lack of diversity in the region — the latest Census indicates that more than 80% of Spokane's population is white — Otero Lockwood says the same argument can't be made for the lack of schools named after women.

"There were only two schools named after women when we started this project to name four or five more schools," she says. "In [my] five-plus years on the school board, we've tripled the amount of schools named after women — which is still only six schools."

Of those women who've been honored, the most recent selection also broke namesake tradition: She's still alive.

PEPERZAK MIDDLE SCHOOL

Two weeks ago, students at Peperzak Middle School gathered together for a schoolwide birthday celebration. The party wasn't for one of their peers, or even a staff member, but for their school's namesake Carla Olman Peperzak, who turned 101 on Nov. 7.

If you imagine a plane taking flight in the middle of a school gymnasium, you might be able to comprehend the shrill excitement of hundreds of preteens scream-singing "Happy Birthday." Peperzak is practically a celebrity to the school's population. Once the celebration was over, at least 30 students swarmed her wheelchair to ask for photos and autographs.

Peperzak is the district's only namesake who is still alive. Because of that, she's been a regular presence at the Moran Prairie school, often sharing snippets of her history with the students.

Born in 1923 in the Netherlands, Peperzak was almost 17 when Nazi Germany invaded the country during World War II. Though she was Jewish, her family found a way to prevent her identification papers from saying as much, according to the Holocaust Center for Humanity in Seattle.

When she was 18, she joined the Dutch Resistance and saved some family members and other Jews who would have been sent to concentration camps. In one instance, she removed a young cousin from a train bound for a killing center by impersonating a nurse, according to the Seattle Holocaust Center for Humanity.

This year, the celebration — which started as an annual tradition when the school opened last year — was extra special as Peperzak, along with the entire student body, found out that the middle school would receive a sapling from the Anne Frank Center. The sapling was grown from the chestnut tree outside Frank's house in Amsterdam, which the Jewish girl wrote about lovingly in her journal before she was found and sent to Nazi concentration camps, where she died in February 1945.

After nearly four years of trying to secure a sapling from the tree for the school, Peperzak says she thought it would never happen.

"I couldn't believe it," she says. "It's hard to explain what a tree means, but it's terribly, terribly important for me."

Peperzak grew up attending synagogue and Hebrew school with Anne Frank's older sister Margot.

When the sapling is planted at the school this spring, it will be one of only 18 of its kind in the country. Peperzak says she hopes to be there when it's planted.

Raymond Sun, an associate history professor at Washington State University with an interest in Holocaust and genocide studies, has been in close contact with Peperzak for the last decade. It was a 2015 story about her in the Spokesman-Review that initially sparked his interest, because she is a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust.

"It's a fairly rare story since most Jews were killed," Sun explains. "Her story is also interesting because she was a woman, and when war came to the Netherlands she wasn't even 17 yet."

Since the pair met, Peperzak has spoken to many of Sun's history classes, which he says makes the lessons more real for students.

"[Students] hearing the story from someone who experienced it is unlike anything I can produce with classroom materials," Sun says. "I think people need individuals to identify with to make the history real. The history lacks a heart and soul and story, but when people can identify with an individual, then it becomes more engaging and understandable, because we're all human."

Earlier this year, Peperzak was awarded an honorary doctorate from WSU, in part for her contributions to student learning through years of sharing her story, Sun says. And even though she won't always be able to talk to students, Sun hopes that having a school in Spokane bearing her name will keep that history alive.

"She won't be around forever. I think the purpose of naming the school after her is supposed to give the district a chance to cultivate the story of this person and use it to impart those values of kindness and respect," he says. "We're about to lose this generation of Holocaust survivors, so it's on us educators to film these stories. We've gotten [Peperzak's] testimony on film, and it will continue to be an effective tool, but it will still be less effective than a real person."

YASUHARA MIDDLE SCHOOL

"Denny [Yasuhara] was always someone who could get the support of the people. He could negotiate with anyone, but he never took a step back because he was adamant for standing up for himself," Dean Nakagawa says. "He was a force for change, for equality, for dignity, and if he saw something wasn't going right, he would always say something. People hated him because he was too honest, too down to earth, too just, but he never wavered on what he thought was right."

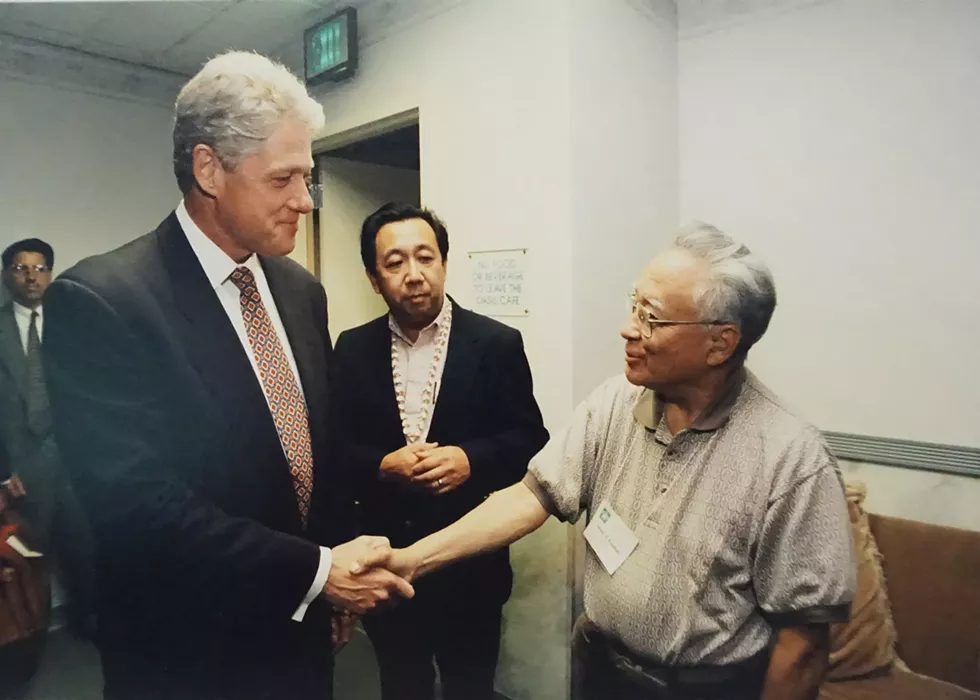

Nakagawa, 77, was born and raised in Spokane's Japanese American community, but he didn't meet Denny Yasuhara until the 1970s. At the time, Nakagawa was president of the Spokane Japanese American Citizens League, and he was working to start a food booth at the Spokane Interstate Fair. Everyone he talked to pointed him toward Yasuhara.

"I finally called him, and he said, 'Sure.' It surprised the heck out of me," he says, recalling the first time the pair worked together. "He came on board immediately, and he organized the oriental food booth at the interstate fair. Then, he organized at least 20 people to build and run the booth for the fair's 14-day schedule."

That food booth would return for another 17 years, but it was that initial meeting in the '70s that sparked a lifelong friendship between Yasuhara and Nakagawa.

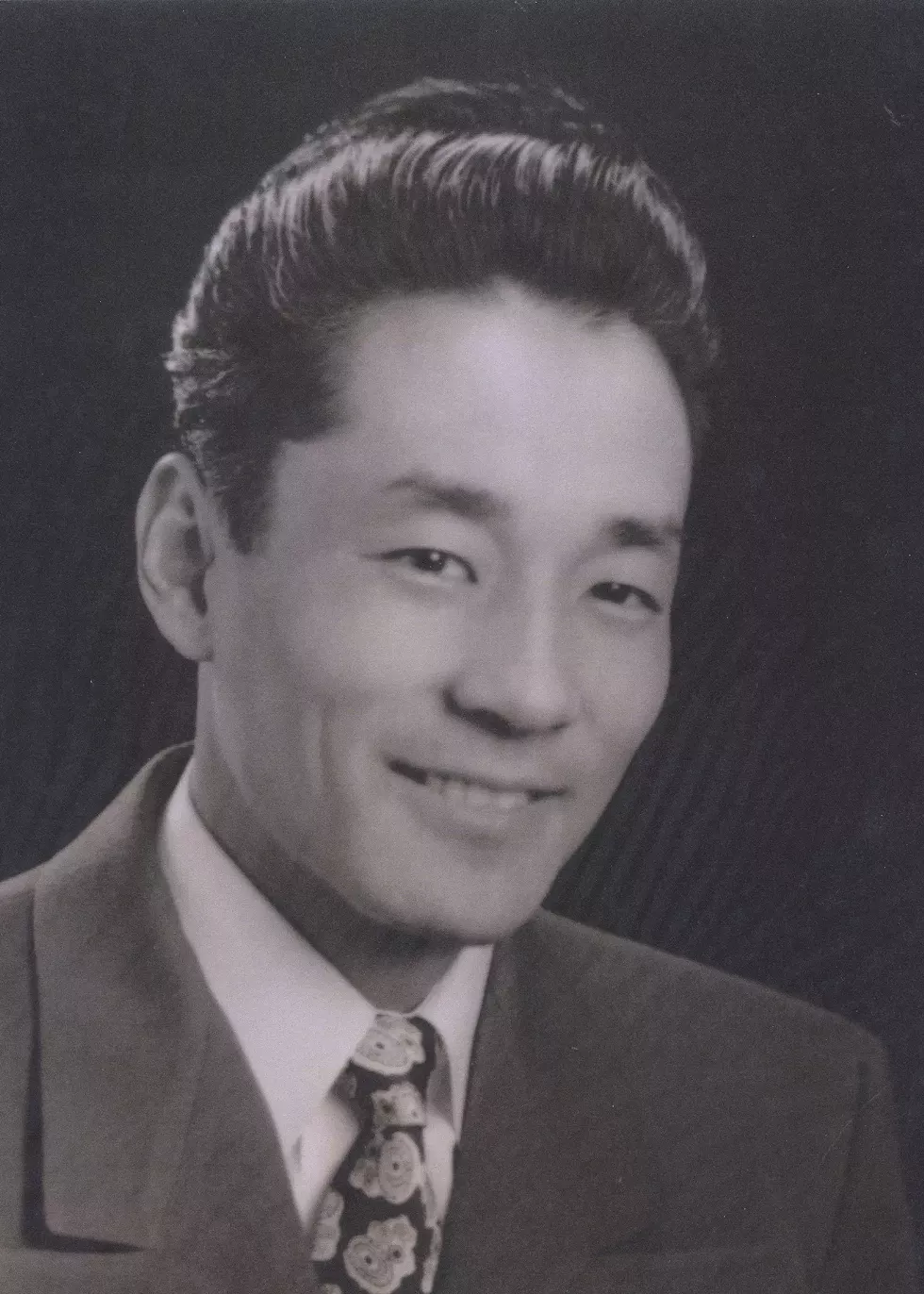

Yasuhara was born in 1926 in Seattle to two Japanese immigrants. However, soon after his birth, his mother died, leaving his father to support four kids, including a 6-month-old baby. Denny was adopted by family friends, the Yasuharas, who lived in Bonner's Ferry, Idaho, at the time.

Yasuhara was just a teenager by the time World War II broke out and President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which allowed the country to incarcerate about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, the majority of whom were American citizens, following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

Due to their location in rural Idaho, the Yasuhara family avoided the internment camps, the Spokesman-Review reported in 2021, but they still suffered harsh discrimination in Idaho.

Nakagawa says Yasuhara would talk about that time sometimes, but not often.

"He was in a fight after school every day, and people would sneer and spit at him," he recalls.

The family ultimately moved to Spokane looking for a marginally larger Japanese American community.

In the 1980s and '90s, Nakagawa says Yasuhara worked with the National Japanese American Citizens League, which is the oldest civil rights group for Asian Americans in the nation. With that organization he fought for reparations for those who were interned during the war. Thanks to the organization's advocacy, Congress passed the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which saw the U.S. government and President Ronald Reagan apologize for the internment and allocate $20,000 for each person who was interned and displaced from their home. He served as the organization's president from 1994 to '96.

"I always thought he was a major force in this advocacy because he was always telling us exactly what was happening as far as negotiations go," Nakagawa says.

Yasuhara's work as a civil rights leader proved vital for the country's Japanese American population, but Nakagawa says his 28-year career with Spokane Public Schools was equally important to him. Yasuhara began by teaching at Logan Elementary School, but later moved to Spokane Garry Middle School, where he taught math and science until he retired in 1989.

"The students loved him because he gave them extra time. He would go early in the morning to open the gym so students wouldn't have to wait outside, and he gave them help to accomplish their higher goals," Nakagawa says. "I remember his wife [Thelma] always asked him why he didn't move up into the administration, but he always told her, 'No, these students need me where I am.'"

Joanne Ferris has fond memories of Yasuhara and her father George Yamamoto together. The two men were close friends, and while Ferris was too young at the time to remember exactly what was talked about inside her home, she says that even as a child she could see the passion Yasuhara had for doing the right thing.

"I wasn't sure what he was talking about, but he really had a fire in his belly," she says. "I could definitely tell that it was a passion to make things right for people who have not been treated equally."

As Ferris grew older, she realized that doing the right thing wasn't always the popular thing as she saw Yasuhara deal with a lot of criticism in his endeavors. Though she says it was that realization that inspired her to become more active in her community.

Ferris is the vice president of the Hifumi En Society, which provides support for Japanese Americans in Spokane and was co-founded by Yasuhara.

Today, the Hifumi En Society is often invited to talk with students, which Ferris says has been a wonderful way to teach them more about their school's namesake.

"When you look at what he's done, not just in Spokane but for Japanese Americans everywhere, it's quite impressive," Ferris says. "Hardly anyone in Spokane knew that someone like Yasuhara pushed a lot of things forward that helped a lot of people. [Naming] Yasuhara Middle School was an important step for us to honor his contributions."

On a cloudy Thursday afternoon in mid-September, Mauricio Segovia welcomes hundreds of students into the large field behind Ruben Trejo Dual Language Academy. Every so often a break in the clouds allows the final rays of summer sunlight to shine down onto the outdoor space.

"Buenas tardes, students," the school principal says with a grin as he offers each passing kid a high-five. "Dame cinco. Give me five, amigo."

Segovia switches between English and Spanish, often repeating words or phrases in both languages as he talks with students. It's an experience that's unique in Spokane Public Schools, as the academy is its first and only school where students receive an entirely bilingual education.

As the school's 290 students begin to settle into their seats, their excited chatter is dulled by the sound of live music from Eastern Washington University's mariachi band, complete with the blaring trumpet, soothing guitarrón and melodic accordion that the genre is known for.

The Sept. 12 event at the school's Spokane Valley campus is serving as an inauguration of the school's first year under a new namesake, Rubén Trejo.

Tanya Trejo and her brother José Trejo, two of Rubén's kids, are both there.

"He was just someone who was very focused on community. He showed that with his art, showed that with how we talked to people," Tanya Trejo says. "So I think it's such a wonderful honor."

José Trejo speaks to the students and families who are now attending a school named after his father.

"I really didn't realize how much he affected the lives of so many people in so many ways," he says. "I think that is the most important part of my memory of my father."

Rubén Trejo was born in 1937 and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota. His parents, Eugenio José Trejo and Esperanza Trejo, were first-generation Mexican immigrants.

In Rubén's younger years, he worked as a farm laborer, but eventually he chose to pursue the arts, according to the Smithsonian American Arts Museum.

In 1969, Trejo earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in sculpture from the University of Minnesota. His work often took inspiration from his Mexican heritage, and infused a sense of humor. For example, his Calzones series of sculptures includes a bronze cast pair of underwear and a jalapeño that is meant to challenge the traditional Spanish machismo culture, according to a book documenting his artwork, Ruben Trejo: Beyond Boundaries, Aztlan y mas alla.

Four years after receiving his degree, Trejo got a job at Eastern Washington University teaching art. In those early years of his 30-year tenure, he worked hard to support the school's small Latino population. By 1977, Trejo had co-founded the Chicano Education Program at the university, which is now known as Chicana/o/x Studies.

Though he worked to protect Latino students at Eastern from discrimination by increasing the resources available to them, he took other measures at home to keep his own children safe in the Inland Northwest, his daughter Tanya says.

"I don't speak Spanish because my father had been so discriminated against for speaking Spanish that he didn't want us to speak Spanish," she tells the Inlander.

"I totally understand, and I think we've come a really long way for that in Eastern Washington," she continues. "So I think it's full circle of someone who wanted to protect his kids from what he experienced as a negative thing, to have his name on a school where it's celebrating people who are bilingual. I think it's really lovely."

School Board President Otero Lockwood says that she is one of the lives that Rubén Trejo touched at Eastern. She was the first person in her family to go to college, so the entire enrollment experience, and specifically securing financial aid, was new and stressful.

While she was able to secure a combination of student loans, scholarships and Pell grants, she says she hit a wall soon after moving into the dorms.

"The Financial Aid Office called me and told me that my financial aid was going to be revoked," she says, recalling the stress of that moment. "I was already in, so I didn't know what to do. But, at the time I had a boyfriend, and his mom worked at a small technical college, and she said, 'Nikki, go to Chicano Studies, they'll help you.'"

She sought help in the department that Trejo had founded, and she was able to quickly find out that there were small technical errors on her financial aid forms — something she says is extremely common for first-generation college students.

"That thing that he created helped me, and if I hadn't gotten that help, I mean, I hope I would have still gone to college, but it just would have been a very different experience," she says, quietly fighting back tears. "You know, we stand on the shoulders of the people that came before us, and that ripple effect of him creating [the Chicano Education Program] reached me directly and so many other students. So many other students." ♦

MORE NAMESAKES

From politicians, doctors and educators to historians and civil rights leaders and activists, many of the schools within the Spokane Public Schools district are named after someone notable. While we've featured three of the district's recent namesakes in this section, below you'll find a collection of other historical figures whose stories pepper the walls of more than half of the schools in Spokane.For this section, we've excluded past U.S. presidents and other national figures, such as Benjamin Franklin, who don't have explicit ties to the Inland Northwest or Washington state and have all been written about extensively.

FERRIS HIGH SCHOOLJoel E. Ferris was born and raised in Carthage, Illinois, but eventually moved to Spokane in 1908 when he was 34 years old. Ferris was a banker by trade, eventually becoming the president of the Spokane & Eastern Trust Company in 1931, according to his Spokesman-Review obituary. Aside from his day job, Ferris' interest in Inland Northwest history was well known. He served as the president of the Eastern Washington State Historical Society. After his death, his donated personal library became an essential part of the society's special collections and is still housed at the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture.

LEWIS & CLARK HIGH SCHOOLCapt. Meriwether Lewis and 2nd Lt. William Clark led the famous U.S. military expedition to explore the Louisiana Purchase and the Pacific Northwest from 1804 to 1806. Many places throughout the region are named for the two men.

THE LIBBY CENTER

Isaac Chase Libby was born in Maine in 1852 and he later moved to Spokane with his wife, Martha, in the early 1880s. Libby is known for his work as the superintendent of Spokane County schools from 1887 to 1891, and later his work as a Greek and Latin teacher at Spokane High School (today's Lewis & Clark High School), according to the Isaac Chase Libby Papers.

ROGERS HIGH SCHOOLJohn Rankin Rogers was Washington state's third governor. Rogers was first elected in 1896 and re-elected to the office in 1900. He died before completing his fifth year in office.

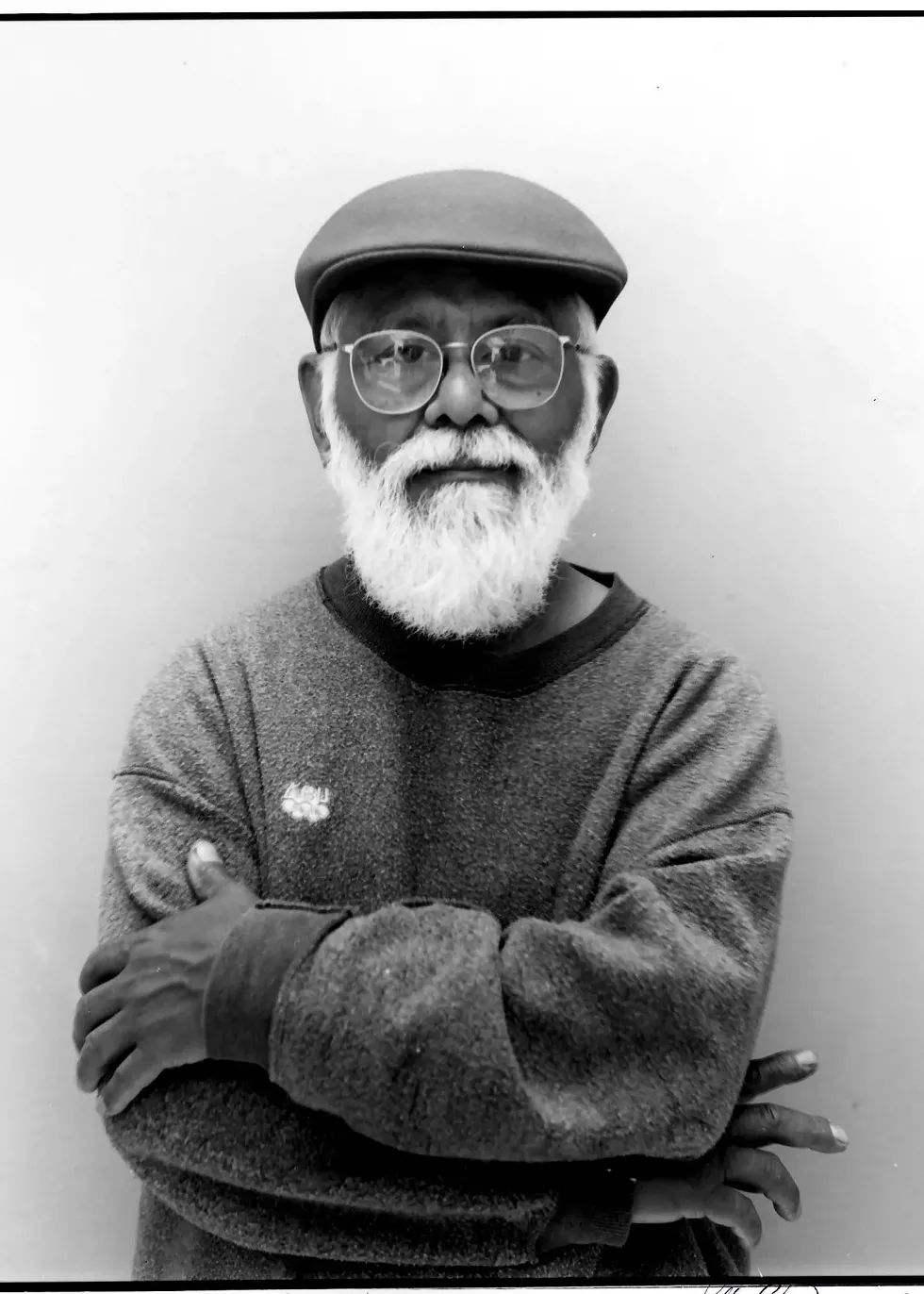

CHASE MIDDLE SCHOOLJames Chase moved to Spokane from Texas in 1934 and spent much of his time in the city working at auto body repair shops, including Chase and Dalbert Body and Fender Repair, which closed in 1981. Chase was also a prolific civil rights advocate, serving as the president of the Spokane NAACP through the entirety of the 1960s. He later made history by becoming Spokane's first Black City Council member after a narrow election victory in 1975. Chase was reelected to the same seat in 1979, and then in 1981 was elected mayor. This election made him the first Black mayor in Spokane and the second Black mayor in Washington state. Chase chose not to run for a second term, and he died in 1987, two years after he left office.

FLETT MIDDLE SCHOOLPauline Pascal Flett grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation speaking her family's native language, Spokane Salish. Flett only learned to speak English when she went to public school, InsideEWU reported, and later co-authored the first Spokane-English dictionary. By the time she died in 2020, the tribal elder was known for her decades of work documenting the Spokane Salish dialect and reviving a once endangered language.

SPOKANE GARRY MIDDLE SCHOOLSlough-Keetcha was born in 1811 to the chief of the Middle Spokane Tribe Illum-Spokanee. At 14 years old he, like many Indigenous youths at the time, was sent to a boarding school in what is now Manitoba, Canada. There, he took on the name Spokane Garry at the requirement of the boarding school, according to Spokane Historical, a public history project at Eastern. In 1828 his father died, so he made his way back to the Inland Northwest where he would become Chief Spokane Garry, serving as a leader for what we now know as the Spokane Tribe. The rest of his life was spent trying to secure a treaty with the white settlers and a reservation for his people. He died in 1892, a few years after a white settler stole his farm and left him homeless, according to the Washington State Historical Society.

GLOVER MIDDLE SCHOOLJames Glover has often been called the "Father of Spokane." When he arrived in the area in 1873, he bought 160 acres of land around the Spokane River and worked to build a city around the picturesque Spokane Falls. The historic Glover Mansion, one of his most notable namesakes, was built for Glover and his wife, Susan, in 1888. However, he later divorced Susan, remarried just days later, and then had his ex-wife institutionalized for the last 22 years of her life. "Glover avoided serious scrutiny in his lifetime and died with his reputation intact," Lisa Waananen Jones wrote for the Inlander in 2014. "But in keeping his first wife out of sight — and out of history — Glover ended up jeopardizing the honored place he worked so purposefully to attain in Spokane's story of itself." In a reckoning with that unsavory history, the Spokane City Council declined to add his name to the plaza outside City Hall in April 2014.

FINCH ELEMENTARY SCHOOLJohn A. Finch was an English immigrant who made his money in the mining industry, specifically at the Hecla Mine in Burke, Idaho. Finch, who would later die in Hayden Lake in 1915, is partially known for his lavish mansion built by renowned Spokane architect Kirtland Cutter in the Browne's Addition neighborhood.

FRANCES SCOTT ELEMENTARY SCHOOLFrances L.N. Scott grew up in Spokane's East Central neighborhood and later spent three decades teaching English at Rogers High School, the Spokesman-Review reported. During her tenure, she earned a Juris Doctorate from Gonzaga University, passed the state's bar exam and became the first attorney in Spokane who was a Black woman.

HAMBLEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOLLaurence Hamblen served as the Spokane City Park Board president in the 1950s and was vital in the creation of the Spokane Parks Foundation. Today, the foundation continues to ensure that the entire city has access to parks and recreational programs.

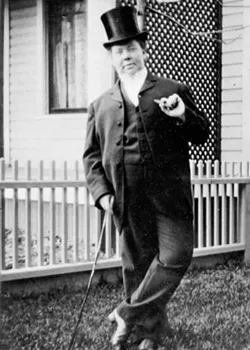

HUTTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOLLevi W. Hutton was a railroad engineer who married May Arkwright (right) in 1887, according to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. The couple made their fortune in Idaho's Silver Valley, and Arkwright Hutton was a suffragist who campaigned locally for women's right to vote. She died in 1915, just five years after Washington state guaranteed women the vote. After her death, her husband went on to found the Hutton Settlement, a home for children that still operates today.

SACAJAWEA MIDDLE SCHOOLSacajawea was born in the late 1780s and likely died in 1812, according to the Brooklyn Museum. Sacajawea was the only woman on Lewis and Clark's expedition, and she was the only member who was not paid. Her regional knowledge proved to be vital to the white settlers' survival, as is evidenced in the journals left behind.

SALK MIDDLE SCHOOLDr. Jonas Salk was a virologist in New York City who developed one of the first polio vaccines, which was determined to be safe in 1955.

SHAW MIDDLE SCHOOLJohn A. Shaw was a North Central High School graduate who went on to teach at the same school and eventually became the school's fifth vice principal in 1924, according to the Washington state Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Shaw then worked as the principal for Havermale Junior High School — which would later become the Spokane Public Montessori School — in 1928, and after a brief period away from the district he became the superintendent from 1943 to 1957.

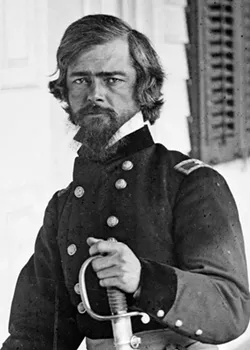

STEVENS ELEMENTARY SCHOOLIsaac Stevens was the first governor of the Washington territory, serving from 1853 to 1857. He used troubling tactics to compel local Native American tribes to sign treaties and imposed martial law to force his control in the territory. He was killed during the American Civil War in the Battle of Chantilly.

WHITMAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOLMarcus Whitman made his way to what's now Walla Walla in the late 1830s to establish a mission. Whitman later led settlers to the West across the Oregon Trail who would encroach on the territory of the Cayuse tribe and wipe out part of their population with a measles outbreak. In retaliation, Cayuse natives murdered Whitman and other settlers in 1847.

WILLARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOLFrances Willard was born in Churchville, New York, in 1839 and spent most of her life as an educator and women's suffragist. She died in 1898, 22 years before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote federally.