It's a really bad time for traffic safety in Washington state.

Car crashes killed 810 people statewide last year, the highest number in 33 years. Drivers are speeding and using their phones while driving more often than they used to. Pedestrians and cyclists are disproportionately represented in the death toll. The number of people getting behind the wheel after using multiple substances at the same time has soared. Drivers seem angrier and more aggressive. Road rage shootings have tripled since 2018.

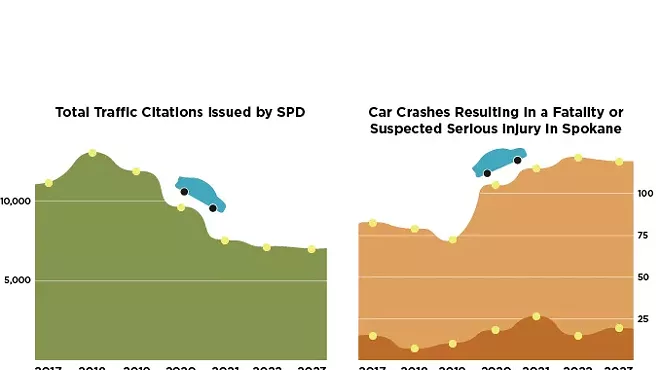

Spokane isn’t immune to the trend. Between 2019 and 2022, the number of fatal and serious injury crashes in Spokane County rose by 66% — from 28 deaths and 107 serious injuries in 2019, to 38 deaths and 183 serious injuries in 2022. Pedestrians represent just 3% of all crash victims, but 23% of fatalities and serious injuries.

Car crashes killed 57 people in Spokane County last year, according to Washington State Department of Transportation data. For reference, that’s more than double the number of people killed in homicides investigated as murders in Spokane County in 2023.

"These aren't just numbers or points on a map, these are members of our own community that are suffering serious ramifications of these crashes," says Mike Ulrich, a principal transportation planner with the Spokane Regional Transportation Council. "That number — that condition — is quickly rising."

To address the crisis, the Spokane Regional Transportation Council — a regional agency with representatives from the city of Spokane, Spokane Valley, Medical Lake and other local jurisdictions — has spent recent months working on a “Regional Safety Action Plan” to reduce regional road deaths and injuries.

The draft of the plan released earlier this week has a bold goal: Zero traffic-related fatalities or serious injuries in Spokane County by 2042.

The Transportation Council received a $400,000 federal grant to help develop its safety action plan. To comply with the federal grant funding, the safety action plan is required to include a "public commitment to an eventual goal of zero roadway fatalities and serious injuries."

For several decades, the Washington State Department of Transportation has had a slightly more ambitious statewide “Target Zero” goal of 2030. Recent trends have made achieving that seem increasingly unlikely. Last year, the state’s Traffic Safety Commission had a roundtable discussion about whether or not to change the goal, but ultimately agreed to keep it.

Ulrich says the Spokane Regional Transportation Council chose the 2042 timeline because it seemed slightly more feasible.

“As we get closer to 2030, the numbers are, of course, going in the wrong direction,” Ulrich says. “I think there was a recognition amongst the [Transportation Council] that it’s not exactly practical, given the immense amount of work that’s going to be required to get to zero.”

The timeline was also chosen to align with the City of Spokane, which also chose 2042 when it adopted its "Vision Zero" project in late 2022. The city was awarded a $9.3 million federal grant to implement the program in December last year.

The action plan released by the Transportation Council this week includes the goals of reducing pedestrian and cyclist fatal and serious injury crashes by 50% by 2030, and halving fatal or serious injury crashes on the Council’s “High Injury Network” — a series of Spokane County roadways with historically high crash rates.

“The group thought that the plan should align with the state in their target of 2030, but also thought we should recognize that, at this point, it seems a bit impractical to get to zero,” Ulrich says.

Once the plan is adopted, local officials will be able to use it to apply for additional funding from the federal and state governments.

Lack of funding has long been a challenge for cities hoping to make safe infrastructure improvements.

On Monday, Spokane City Council members are planning to vote on a resolution that aims to help address funding issues by asking Mayor Lisa Brown to direct the Public Works Department to implement "adaptive design" strategies for transportation projects across the city.

Adaptive design refers to temporary measures designed to slow drivers and are cheaper and easier to install than typical traffic calming projects, which are often made of concrete. Adaptive designs have been used in other cities, and often involve planter boxes, painted intersections, bollards and other low-cost enhancements that make roads safer for pedestrians and cyclists.

City Council member Zack Zappone, who introduced the resolution, has said it is intended to address challenges with traffic calming projects being delayed because of a lack of staff capacity and funding issues.

"It's really cost effective," Zappone said at a meeting last week. "We're able to get more of these types of interventions out across the city faster so more neighborhoods, more people, are able to have a safe experience."

THE PLAN

The Transportation Council's plan includes a list of 34 recommended action items for state agencies and local jurisdictions. The recommendations include a variety of infrastructure improvements, as well as new approaches to education and traffic enforcement. They do not include cost estimates.

After the action plan is formally adopted by the Transportation Council in July, local jurisdictions will be able to choose how exactly they want to adopt it and follow through on the recommendations.

“We wanted to leave some flexibility for our members to be able to design a project that fits in their community, so we’re not trying to be overly-prescriptive with all the recommendations,” Ulrich says. “We proposed a menu of strategies that they can choose from.”

Achieving zero deaths and serious injuries by 2042 might be slightly more feasible than the state’s goal of 2030, but it’s still an ambitious target. Transportation projects take a lot of time, and 18 years can pass quickly.

Ulrich is cautious when asked how confident he is in the region’s ability to meet the 2042 target.

Transportation planning is a matter of prioritizing competing demands for resources, Ulrich says. Funding is always limited. Safety is a top priority, but many cities also struggle to find money to address transportation maintenance, capacity and congestion issues.

“To the extent that we can get the funding necessary to implement the plan, yes, I’m fully confident that we can get to zero by 2042,” Ulrich says. “I’m just not 100% confident that funding exists out there.”

Ulrich stresses that achieving zero deaths and serious injuries is possible. It's happened in other communities. He points to Hoboken, New Jersey — a city of about 60,000 that adopted a Vision Zero action plan and has been without a traffic fatality for seven years.

The draft action plan’s 34 recommendations are broken up into five subsections: "speed management," "angle crashes," "education," "run-off-the-road crashes" and "pedestrian and cyclist."

Many of the recommendations involve infrastructure changes like narrowing lanes, adding guardrails, reducing the number of lanes, and installing roundabouts and protected pedestrian crossings. It recommends lighting improvements in high crash areas, and speed feedback signs and rumble strips ahead of severe curves.

When it comes to traffic enforcement, the plan recommends increased use of automatic red light and speeding cameras, and for police departments to prioritize increased traffic enforcement in the top crash zones.

Ramping up enforcement could be tricky. Last week, we reported on how the Spokane Police Department's traffic enforcement has waned in recent years because of ongoing staffing issues.

For education, the report recommends that local agencies partner on an outreach campaign focused on distracted and impaired driving, speeding, and vulnerable road users like pedestrians, cyclists and youth.

People can get an overview of the plan and participate in a survey about their traffic safety priorities here. A copy of the full plan is available here.