These days, Gov. Jay Inslee, the Democratic presidential contender who still happens to be the governor of Washington state, is a little hard to get on the phone.

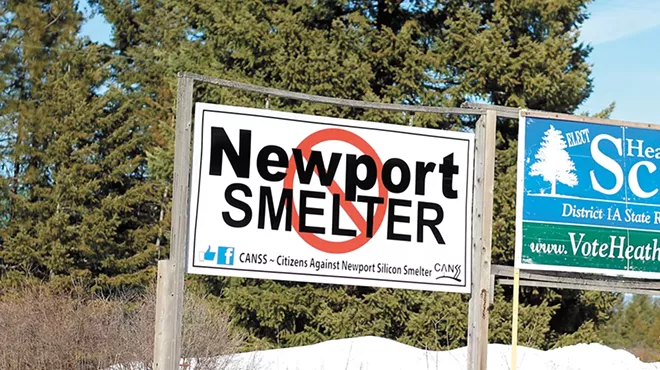

The Inlander recently tried for weeks to get on his schedule and wasn't successful, though it likely didn't help that reporting for our recent update on a proposed silicon smelter near Newport coincided with the end of this year's legislative session and some campaign travel out of state.

But that schedule doesn't much matter to opponents of the proposed PacWest silicon smelter in Northeast Washington that's backed by Canadian company HiTest Sand. They still want to know how a governor who worked to pass some of the most aggressive climate-centered legislation in a decade can square his climate-focused agenda with support for what would be one of the largest polluting businesses in the state.

Other commenters regularly question support for the smelter, which might emit up to 766,000 tons of greenhouse gases each year. That estimate comes from the Department of Ecology webpage for the PacWest environmental study, but HiTest President of U.S. Operations Jayson Tymko questions the figure as too high.

But the estimate Ecology has comes from draft air modeling it has been working on with the company's contractor. The figure that's been cited in multiple drafts of that modeling, which is based on a two-furnace, one stack smelter (the facility could double in size eventually), is 766,131 tons of greenhouse gas emissions. That would put the project would on par with a small oil refinery in the state, and on the short list of top emitters.

Inslee's advisers, however, are quick to argue that while the governor did work with the Department of Commerce to support the proposal as a project of statewide significance, giving it $300,000 in startup money back in 2016, that doesn't mean he supports it outright.

What his office supports is putting the project through the required environmental testing that will spell out potential risks and steps that could be taken to reduce any negative impacts, explains Robert Duff, Inslee's senior adviser on the environment.

"We support them going through the process," Duff says. "We support them trying to locate here, we want business to locate in rural Washington. But we need them to go through the process so we get a full understanding of the impacts."

That means going through not only the federal testing required by the Environmental Protection Agency, but also through a full environmental impact study (EIS) required for an air quality permit under the State Environmental Policy Act.

But the EIS has been put on hold as the company waits for permitting changes in Pend Oreille County before ponying up what could be much more than anticipated for a contractor to do the environmental work.

That's putting further delay into the EIS process, which can also be frustratingly long for some folks.

"These big projects need scrutiny, and that's why it takes so long," Duff says. "It frustrates people on both sides of this. It takes time for information to come out and they've only got drips and drabs of information."

The Kalispel Tribe of Indians opposes the smelter, and initially felt blindsided by the proposal, which was announced well ahead of environmental work starting at the state level. Since the announcement of the project, the tribe has been working to redesignate the air shed over its reservation to Class I, the strictest standard that's often used for national parks and wilderness areas. As the reservation is close to the smelter site, that designation could help inform an eventual permit decision.

Smelter opponents also frequently ask what's different between this project and other polluting proposals that in recent years have been blocked from going into the state, such as the Gateway Pacific Terminal at Cherry Point. In that case, it was found that tribal treaty trust rights would be infringed, Duff says, but all of the projects that have been stopped have gone through a full environmental study process and the information gathered informed the decisions.

The PacWest project is no exception, he says.

While Inslee initially voiced enthusiasm that HiTest shared the same clean energy goals as the state — silicon metal can be further refined for use in solar panels, as well as computer technology and hundreds of other uses — the project will still have to go through a full study. Only then will agencies decide if it can receive needed permits.

"The big point of that is you’ve got to get it right," Duff says. "Get the information everybody needs, and of course, that the agencies that need to issue the permits need."

This post was updated Tuesday, May 14, 2019, to clarify that the emissions figure cited by Ecology came from a contractor working for PacWest, and is the estimate the company has provided in working on modeling.