The tiny pill melted onto a piece of foil in the middle of the clear afternoon. The 20-somethings inhaling its fumes had just broken into two houses in north Spokane County — the last in a string of at least 40 burglaries investigators would later link to them.

In the span of a month and a half in the summer of 2014, Damian Zowal and Trever Burzic hit house after house after house in isolated neighborhoods. They made off with electronics, cash and coins. They took a high school class ring, a grandmother's engagement ring, a late husband's billfold, a fly fishing rod, car titles and a silver teardrop pendant with the ashes of a victim's father inside. In particular, they looked for guns.

Spokane County sheriff's detectives arrested the duo in their red getaway car. Zowal had a pistol in his pocket. He told detectives he carried the gun with him into every house because he would rather shoot someone than be shot.

They racked up 200 felony charges. Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich called a news conference at the time, saying "we have a property crimes issue because we're not holding property crimes suspects accountable for their actions." Burzic's own uncle expressed relief: "At least they got him off the streets before somebody got killed."

Judge Harold Clarke pointed to their drug addiction, recommending that when the two were released, they should receive state supervision.

But after eight months in prison, they're out. And thanks to a state Department of Corrections formula that overrode the judge, nobody's watching them.

"I can order all the supervision in the world, but if the programs and resources aren't there... " Clarke shrugs. "When judges sentence someone to supervision, they don't know if that will be carried out, and even the offender doesn't know until they're released."

Washington is the only state in the nation that doesn't supervise property crime offenders after they're released from prison, other than the occasional specialized sentencing alternative. Washington also has the nation's lowest number of law enforcement officers per person.

So it shouldn't come as a surprise that Washington has the highest property crime rate in the nation, according to the FBI's latest available data. Washington can't blame it all on geography or poverty, either. Idaho, despite high poverty levels, has a property crime rate less than half the rate of Washington's.

So when Sabrina Schoenberger came home to broken glass scattered across her bedroom floor, her dresser drawers tossed throughout the room and her pistol missing from the nightstand, the violation felt almost routine. It was the third time her rural Spokane County house had been burgled. Detectives tied Burzic and Zowell to the most recent crime. The other two cases were never solved.

"It's just part of living out here," Schoenberger says. "You can alarm and deadbolt all you want, but if they want in, they're getting in."

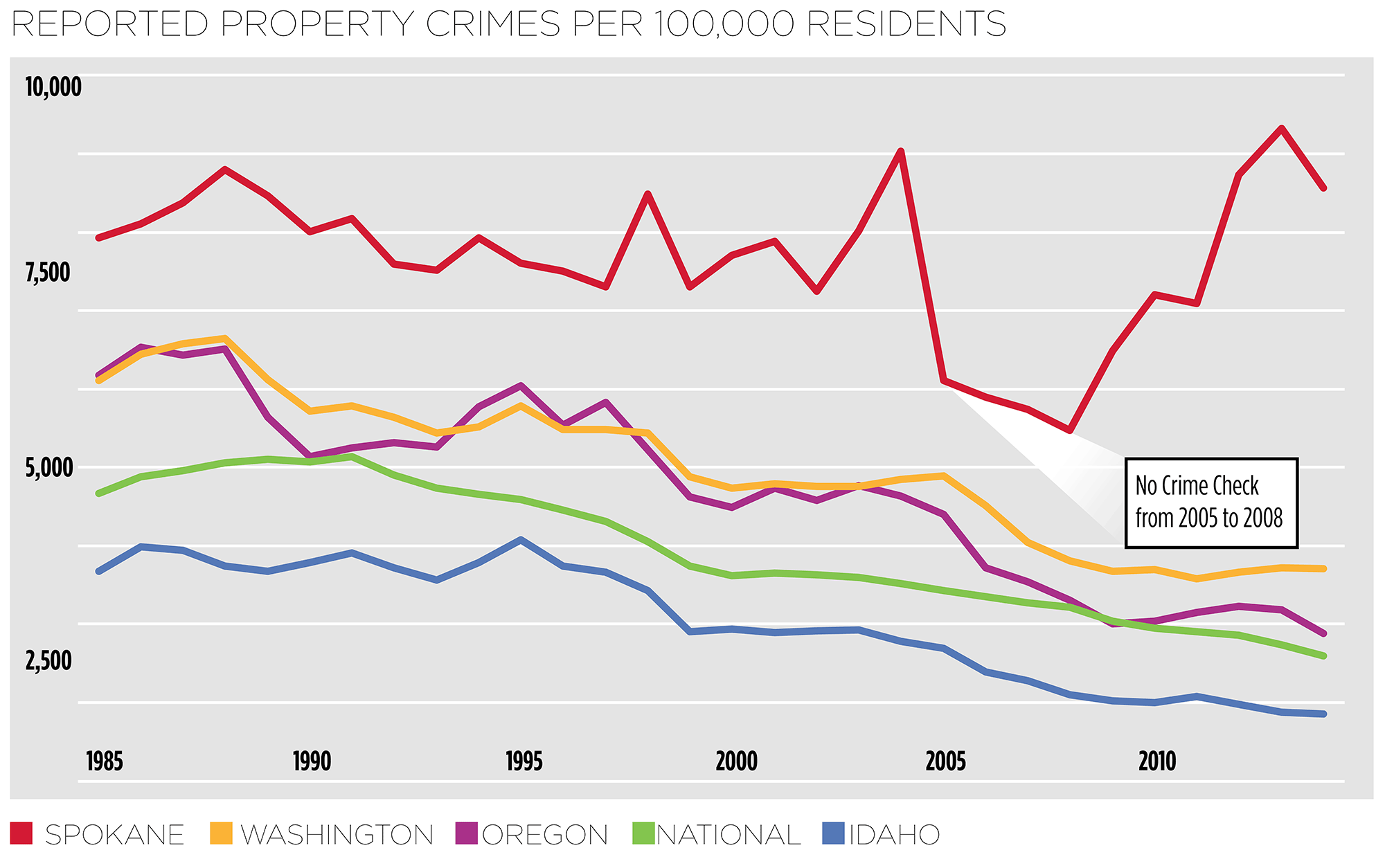

From 2009 to 2013, despite the recession, property crime rates nationwide dropped by 11 percent. But in Washington, crime ticked up slightly. And in Spokane, property crime soared to record levels.

Last year, Gov. Jay Inslee's Justice Reinvestment Task Force issued a sprawling report, laying out all the problems with supervision, sentencing and policing that drives property crime — only to see a proposal to fix it stall in the legislature.

At play is the fundamental tension of criminal justice reform: Should Washington play good cop or bad cop? Should it ratchet up penalties for property crime offenders, increase jail sentences, increase supervision, build more prisons and put more cops on the streets? Or should it focus on treatment, hoping that through Smart Justice techniques, the most prolific criminals can be rehabilitated?

Right now, Washington is doing neither.

COPS AND ROBBERS

For two decades, Stevie Sivertsen says, he was addicted to meth, heroin and property crime. In the living room of his Spokane Valley home, Sivertsen lifts his shirt to show the prison tattoo of a fist clenching a lightning bolt across his hairy torso. "Hate stuff," he says, apologetically.

Sivertsen's record is piled sky-high with felonies and misdemeanors, including drug possession, assault, counterfeiting and an in-transit escape from a Geiger Corrections Center van. But his speciality was property crime. He'd kick through glass doors and slice through safes with a saw. He'd steal cell phones, TVs, music players, Seahawks season tickets. He had a garage stacked with stolen bike parts.

"Any bike above a couple of grand is worth $150 in dope," Sivertsen says.

He'd steal diabetes equipment: The test-kit bag was perfect for holding needles and a bag of meth. He'd steal oxygen tanks: They can be sold for scrap. He'd speed straight for school zones when chased by the cops: The police wouldn't risk endangering children, but he would. "Just pull over, just pull over," he remembers his buddies in the car pleading. He wouldn't.

Blame the meth. Before bursting into a room to rob drug dealers, he would take a hit. Meth makes some people paranoid. It made him fearless.

"There are no sober people committing the crimes you're talking about," Sivertsen says. "If you can address the drug problem, you will have addressed the property [crime] problem."

In the past two National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Washington ranked fourth in its percentage of residents who admitted to recently using illicit drugs other than marijuana. Deaths related to heroin or other opiates in Washington have risen.

The days of Spokane meth lab infestations are largely over, wiped out in part by stricter regulations and mandatory minimum sentences for cooking meth, says Capt. John Nowels of the Spokane County Sheriff's Office. But cheap meth from Mexico rushed in to fill the void.

"Three years ago, an ounce of meth would have cost $1,500," Nowels says. "Today, about $400."

Veteran Spokane County property crime detective Dean Meyer snaps on a pair of blue rubber gloves and thumbs through an envelope jammed full of other people's mail that he just seized from a suspect's car. Sitting on the floor below the bundle of stolen checks and credit cards is the suspect's gym bag. He pulls out a small scale with sludgy black resin smeared onto it. Next he pulls out a syringe loaded with more of the tar-like heroin.

Almost all the property crime he investigates is driven by addiction, Meyer says — meth, heroin, pills.

For the past decade, Meyer's job has been hunting property criminals. Usually he juggles five or six cases at a time; right now he has 10 open cases. No matter how hard he works, there are some cases that Spokane detectives just can't investigate.

"A stolen card can be used once and it can take a month of an investigation. And we'll have five or six of these a day," he says.

Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart says that with the region's high poverty rate, low tax revenue makes it tough to hire more officers.

"It's a tough chicken-egg thing," Stuckart says. "How do you improve your economy if you have crime? And how do you pay for more officers if you don't improve your economy?"

Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich sees the same problem. In 2008, faced with an overcrowded jail, advocates started looking for ways to reduce the population rather than build a bigger facility. At the same time, Spokane County slashed $1.5 million from its criminal justice budget.

"We don't have staff to really do the job we need to do, and even if we did, the way the system is, they turn 'em right back out on the street," he says. "They don't have the money to hold them in jails or prisons, and they don't have the money to do any kind of Smart Justice."

Sivertsen saw firsthand how an overburdened criminal justice system and the quirks of Washington law conspired to make the state the ideal habitat for an unrepentant thief.

When he moved from Alaska to Washington in 2003, he remembers being confused the first time he was booked, and then suddenly released after three days. He told his buddies, worried they would think he cut a deal with the cops to get out so quickly.

"And they said, 'No, you idiot,'" Sivertsen says. "'That's Washington.'"

Washington releases most nonviolent arrestees within 72 hours if charges aren't filed. Historically, overwhelmed police and prosecutors in Spokane have frequently failed to meet that deadline. A 2008 report found that on average, it took 57 days after booking for charges to be filed. Back then, Spokane Superior Court Judge Maryann Moreno says, prosecutors only met the 72-hour deadline in about 10 percent of the cases. Sometimes it would take police and prosecutors years to bring charges.

That issue was exacerbated by another aspect of Washington law: After racking up enough thefts on a criminal record, additional thefts don't automatically result in additional prison time. So whenever Sivertsen landed back on the street — waiting for prosecutors to eventually get around to filing charges against him — he knew that more crime wouldn't mean more time.

His crime sprees continued unabated: He'd take bolt cutters to garage doors, shoplift from grocery stores, snag bikes from college campuses, strip wiring out from abandoned houses. And he would feel immune from the consequences.

"There was no fear of a longer sentence," Sivertsen says.

The "free crimes" problem has long plagued Washington. In 1991, prosecutors successfully argued that unless the state Supreme Court allowed an exceptional sentence for the defendant, offenders with high criminal records "would be free to commit 20, 50 or 100 additional burglaries without any additional punishment."

Spokane County, at least, has tried to fix both issues, says Tony Hazel, a county deputy prosecutor. The county has dramatically cut down the time it takes to file cases, by doing things as simple as having the police send electronic copies of police reports. Today, it's rare that a criminal is released because they're not charged within 72 hours.

When Larry Haskell took over the Spokane County Prosecutor's Office in 2015, Hazel says, he issued a decree: For repeat extreme property offenders like Sivertsen, prosecutors would always ask for exceptional sentences. The more you steal, in other words, the longer you'd spend behind bars.

But by that time, the city of Spokane had already suffered three years of its worst property crime epidemic in decades.

THE EPIDEMIC

If you want a moment when property crime got really bad in Spokane, point to October of 2011: That's when the Spokane Police Department officially announced it would eliminate the property crimes unit.

"If it's just your car got stolen and you don't know who did it, you're probably not going to get an investigation from us," Officer Jennifer DeRuwe, then the department spokeswoman, told the Spokesman-Review. "It totally sucks for everybody in the community."

Mayoral candidate David Condon called this decision a mistake, and rode a campaign promise — to develop a response to burglaries and car thefts within his first 100 days — to a surprise election victory.

The police department later indicated that the announcement was overblown; that despite reorganization, property crimes were still being investigated.

But the statement had already done its damage. "That was the worst thing ever done in this community," Knezovich says about the statement. "It sent a message: 'open season.'"

Indeed, crime shot up in November 2011, and the following year Spokane suffered the worst property crime rate in years. In the first nine months of 2012, there were more burglaries and larceny than in all of 2009.

For three years, crime remained there at its high-water mark. In 2013, the city of Spokane's reported property crime rate was the highest it's been since at least the mid-'80s. That year, a middle-aged Spokane plumber shot and killed a 25-year-old car thief who was driving away with his SUV. Even Stuckart's house got hit in 2013.

"My back door got slammed in," Stuckart says. "They stole all my wife's jewelry, all my grandmother's jewelry, and my food scale."

That's not to say that Condon hasn't worked hard to treat the property crime epidemic. The data-wonk mayor hired (and later ousted) a data-wonk police chief. The police department started tracking crime stats to identify "hot spots" and guide patrol officer coverage. The police allied with neighbors to identify concerns, targeted drug houses and blighted apartment buildings, and worked with Avista to amp up the brightness of streetlights.

Twenty-five more officers have been hired by the Spokane Police Department. Even choosing the classic black-and-white for the new police vehicle paint job, Condon says, was made with the intent of deterring crime by increasing police visibility.

Condon has requests for the legislature as well: Make vehicle prowling a class-C felony. That's what Idaho does. Treat scrapyards like pawnshops, requiring ID to be shown before anything is sold.

Since approximately 2012, Spokane's criminal justice players have advocated for Smart Justice, aimed at decreasing jail population through effective data collection, improved interagency communication and diversion courts. Early indications suggest that all of these efforts have made a difference: Preliminary Spokane property crime figures finally ebbed last year, falling back down to 2011 levels. (Those figures have issues, however. See "The Trouble with Crime Stats" on page 25.)

Asked if he's accomplished what he set out to do with property crimes, Condon is unequivocal. "Oh, gosh no. No, no, no," he says. "Are we going in the right direction? I believe we are."

The hope is that it sticks. Property crime seems to be ticking back up in the first months of this year. Condon knows there's another danger; that eventually, people will get so sick of being victimized, they'll stop bothering to tell police. Official crime rates will decline, but actual crime won't.

"There's an apathy level," Condon says. "If people don't think you're going to do anything, then why report it?"

UNSUPERVISED

In 2003, the state dropped the number of criminals under state supervision from 65,000 to 30,000, cutting loose essentially all property crime offenders. In 2009, the legislature eliminated supervision for another 14,500 criminals — not just those with misdemeanors and property offenses, but those guilty of drug dealing, assault, sex crimes. Even murder.

To be fair, the cuts weren't made blindly. The Department of Corrections aimed to cancel supervision only for those unlikely to reoffend.

"You could do more harm by actively supervising those low-risk offenders," says Debbie Conner, field administrator for the Department of Corrections. For them, too much contact with the criminal justice system can actually backfire.

As a result, the agency uses a risk-assessment tool, a scoring sheet that calculates whether an offender qualifies for supervision. That's the tool that can override even a judge's orders.

Yet those property crime offenders in Washington who don't qualify for state supervision are actually the most likely to reoffend. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report, 82 percent of property crime offenders released from prison in 2005 were arrested within five years for a new crime, a higher rate than any other type of offender.

As a general rule, the more times a burglar gets sent to jail, the longer the prison sentence. But no matter how many property crime convictions they rack up in Washington, they'll never qualify for supervision.

Recently appointed Spokane City Councilman Breean Beggs, an attorney and leader in local Smart Justice reforms, suggests that Washington's priorities are precisely backward.

"Every extra day, month, year someone spends in prison, they are more likely to commit crimes when they get out," Beggs says. Instead, he says, prison funds could be spent on treatment, mental health care, and, yes, supervision for offenders.

Supervision was the No. 1 focus of Inslee's Justice Reinvestment Task Force report, which called for less jail time and more quality supervision. A Pew Research Center study in New Jersey found that offenders receiving supervision were 36 percent less likely to end up back in prison in the next three years.

Washington, for its part, is trying to hone its algorithm and get smarter at determining which criminals need supervision and which need simply to be held behind bars.

In that light, the state asked Washington State University criminal justice professor Zach Hamilton to design a new diagnostic tool intended to more accurately calculate a person's likelihood of reoffending and need for treatment.

The new tool, which Hamilton expects to be implemented by early 2017, considers criminal history, education, employment, family and social ties, attitudes, aggression, mental health and substance abuse issues to mathematically individualize each person. The current assessment scheme only considers criminal history.

Spokane police, too, are trying to compensate for DOC's lack of supervision. The "chronic offender unit" focuses on "up and coming" criminals — people who are starting to show up more frequently in reports and have one or two convictions to their name.

"It's just a little bit more contact and follow-up than you would normally get from the police in a nontraditional criminal justice manner," says SPD Sgt. Terry Preuninger, who is in charge of the unit.

Recently, though, due to a reorganization, the unit's four patrol officers were reduced to two.

JUSTICE AND MERCY

Last year, state Sen. Jim Hargrove — the same Democratic senator who once sponsored two bills that slashed supervision — proposed a major bill that would have shortened the prison sentence of many property crime offenders, but also tacked on a year of post-release supervision.

"This bill will make citizens safer, reduce property crime in the state, and save the state money," Hargrove said.

While it passed the Senate by a sizeable margin — even winning the vote of famously tough-on-crime Spokane Valley Sen. Mike Padden — it never got to the floor of the House.

This year, any attempts to revive property crime reform have been drowned out by the much more flashy fiasco in the Department of Corrections: A computer glitch, which remained unfixed for more than a dozen years, resulted in 3,200 offenders being released early statewide. As Padden blasted the Inslee administration for the error in a December 2015 press release, he criticized the notion of trading prison time for supervision.

Padden says he and Hargrove are still talking about property crime reform. He thinks that supervision would help, but wants to pass legislation giving prosecutors increased ability to seek longer sentences for particularly untreatable repeat property offenders. "This is somebody who's had all sorts of chances, and still continues to offend," Padden says.

Yet, redemption and reform, even for a guy like Sivertsen, can be possible. His crime sprees stopped after 2007. For him, the key was a program while he was locked up, where a couple of fellow convicts helped him identify the childhood trauma driving his drug addiction.

"I was finally able to determine why I had to use," he says. To that, add the clean and sober housing he was placed in directly out of prison. And to that, add the post-prison education program that eventually allowed him to get a legitimate job building airplane parts.

Now he's a devout Seventh-day Adventist, the sort with a drawing of Jesus hanging in his living room and Strong's Concordance on his bookshelf. He volunteers to help place offenders in clean and sober housing.

He's on the other side now: Like so many in Spokane, he's been a victim. Just last month, he had an Amazon package stolen off his porch. But he doesn't feel anger. He feels pity and understanding.

"I know exactly how it happens," Sivertsen says. "I hope they reach their bottom fast, and get help." ♦

IDAHO'S SECRET

While Washington has the highest property crime rate in the nation, its neighbor to the east — Idaho — is among the lowest. Maybe Idaho's tougher criminal penalties can be credited, or the fact that Idaho's prison population has doubled in a decade.

But there's a lot more to it than that: About half of Idaho's felons receive probation instead of a prison sentence, an alternative practically nonexistent in Washington. Nearly 15,000 Idaho offenders are on probation or parole, and a quarter of them are property offenders. A major part of that is drug testing.

"Our drug testing is going to be significantly ramping up," says Kevin Kempf, director of the Idaho Department of Correction. "Many times when you ask, 'What do you need me to do to help you be compliant?' so often they tell you, 'I need to be drug tested often. I need to get drug tested twice a week.'"

Washington also has treatment programs behind bars. But prison stays for property offenders are often too short for the programs to be effective, and the lessons in prison don't always translate to the outside.

"The experts say that even with the absolute best program you can think of, in the prison setting the needle is not going to move that much," says Kempf. "It's not a realistic setting."

Idaho isn't satisfied. The state is pursuing its own criminal justice reform, hoping to cut its high prison population without affecting its low crime rate. It's launching a community mentor program, pairing parolees with a volunteer to help them transition back into society.

"You can't just isolate them and put them on house arrest and think they're going to do well, because they won't," Kempf says. "We will not be able to surveil our way to public safety." (DANIEL WALTERS)

THE TROUBLE WITH CRIME STATS

While statistics show that both Washington and Spokane have sky-high property crime rankings, trying to draw precise conclusions from the FBI's national stats brings up a big issue: They only include crimes the police know about. If citizens are unwilling to report crimes, the crime rate looks lower.

The classic example: In 2005, Spokane County eliminated Crime Check, the number that citizens can call to report non-emergency crimes. Poof, crime seemed to fall. But when Crime Check returned in 2008, it seemed to rise.

The other problem is how you count crimes. When Spokane Mayor David Condon celebrated an apparent 18 percent drop in property crime in his State of the City speech last month, he was relying on info from CompStat, a granular crime-tracking tool famously used by the New York Police Department.

But CompStat data is preliminary and messy. For instance, CompStat only tracks the last full week of the year. The result? Spokane's final report for 2013 tracked two more days of crime than it did in 2015. It has never tracked crime on New Year's Eve.

Each year, the disparity between Spokane's CompStat data and the data the Spokane Police Department sends to the FBI has grown. In 2014, the data sent to the FBI shows 1,447 more property crimes than the CompStat reports do.

The biggest reason? Unlike the NYPD, the Spokane Police Department wasn't including attempted property crimes in its total for CompStat property crimes. It does include those crimes in the figures it sends to the FBI. So between 2012 and 2014, the FBI's stats show the number of property crimes known to SPD falling by a modest 2.5 percent. But look at CompStat's figures, and the decrease looks three and a half times larger.

It could be worse: In New York, cops have been caught "juking the stats," giving serious crimes, like burglaries, less serious classifications, like "criminal trespass," to make it look like crime is falling.

This year, Spokane has started listing attempted property crimes in its CompStat reports. Later this year, another big change is coming: Instead of only counting the most serious crime — a burglary where a surprised homeowner is assaulted would just be classified as an assault — SPD will count each crime separately.

That's right: Those high crime numbers actually underestimate the level of property crime in Spokane. (DANIEL WALTERS)