For communities that eat a lot of fish, it was a victory when the Environmental Protection Agency stepped in to say Washington hadn't gone far enough with its new water quality standards in 2016.

At the time, the state was being required by the courts to update its limits on nearly 100 pollutants that can impact human health.

The standards are based on how much people would be exposed to various chemicals and their risk of getting cancer if they eat a set amount of fish on average. As part of the update, the state increased the "fish consumption rate" it uses to set those standards to be protective of people who eat 175 grams of fish per day (roughly a 6-ounce filet).

That was good news for Native American and Asian American communities, who typically get much more fish in their diets and therefore run higher risks from pollution in local water bodies.

But it was an even larger win when the EPA found that 143 of the 192 human health criteria that Washington submitted weren't strict enough and required the state to instead hold dischargers to stricter federal standards.

Now, however, that could all change as the EPA says it is listening to a 2017 petition from industry and business interests that asked the federal agency to reconsider.

With the petition, business groups including Greater Spokane Incorporated ostensibly went to bat for the state, arguing its science was sound and plenty protective of human health. Plus, they argued, EPA's stricter standards would be prohibitively expensive to meet and in some cases, not possible with current technology.

"In pursuit of its political agenda EPA ignored substantial and overwhelming evidence that its final human health criteria afford no benefit to public health over the Washington-submitted standards, while imposing potentially billions of dollars in additional regulatory and compliance expenses," the February 2017 petition to the Trump administration reads. "We respectfully request that EPA reconsider the human health water quality criteria adopted by the state of Washington."

On May 10, they got their answer. Chris Hladick, regional director for EPA Region 10, wrote a letter to Department of Ecology Director Maia Bellon, letting her know the federal agency would rescind its disapproval for 14 g1 of the 143 criteria. Therefore, the state would follow the lower standards the EPA ruled weren't strong enough in 2016.

For some chemicals like zinc and chloroform, that means the limits would be twice as much as they would have been under the federal rules. For other chemicals, the difference is even more extreme.

The reversal has environmentalists and tribal and state leaders up in arms, as they worry this move would be a huge step backward for environmental protection, allowing more pollution to be dumped into waterways and putting people at higher risk of illnesses over time.

What's more, while the EPA appears to be taking the state's side, clarifying Washington can set lower standards, state regulators say that making this decision this late in the process disrupts years of work implementing the new rules. In 2016, the state opted not to fight the stricter requirements. Changing things now only causes uncertainty and confusion, Bellon told the EPA.

"He always said, 'You know, son, this is going to be the next fight not just for salmon, but for humans.'"

"We didn't ask for this," Bellon wrote in a May 10 Twitter post. "We told @EPA no. Repeatedly. By undoing its own 2016 clean water law, EPA has thrown us into a state of limbo with no end in sight. In this Washington, we value environmental progress and collaboration. This is neither of those."

Even as EPA's reversal appears to be offering the state more authority to set its own standards, at the end of the day, the federal agency still has to sign off on the limits. So in order to stick with the stricter standards, Washington would need to start the yearslong bureaucratic rulemaking process all over again.

There's no official timeline yet for when the EPA reversal will officially take effect, and it will go forward for public comment before that happens. But already the stage is being set for court challenges.

"There is no legal basis for reconsideration of the standards," Bellon wrote to the EPA in May. "To repeat, Washington does not seek revision or repeal of the standards set in 2016. To the contrary, we steadfastly oppose any revision or repeal."

For many tribes, the announcement was frustrating on multiple levels, as the EPA didn't consult with tribal governments before deciding it would loosen the standards.

"It's very unfortunate the EPA is coming in and deciding to roll things back," says Willie Frank III, a Nisqually Tribal Council member. "These standards they're going back to makes it even tougher for us to eat salmon and live off salmon. Some of our elders still eat a traditional salmon diet."

Protecting rivers and the environment are of the utmost priority to many tribes throughout the Pacific Northwest. Rivers and the fish they're home to tend to have significant sacred meaning. Frank, son of the late Billy Frank Jr. who fought for treaty-protected tribal fishing rights during the Fish Wars of the '60s and '70s, says he compares it to church.

"For us, being able to be on the [Nisqually] River is good medicine for our people. It's how we connect to our parents, our grandparents and our ancestors," Frank says. "I hear my dad's voice everyday in the work that I do. I always remember him talking about the importance of water. He always said, 'You know, son, this is going to be the next fight not just for salmon, but for humans.'"

While tribal communities are likely some of the most impacted by changes to pollution standards, those standards are there to protect everyone, says DR Michel, executive director of the Upper Columbia United Tribes, whose members include the Coeur d'Alene, Kootenai, Kalispel, Colville and Spokane tribes.

He sees this as yet another move in the wrong direction when it comes to environmental policy under the Trump administration.

In just the past few months, the EPA under Trump has proposed significant reductions to the list of water bodies protected under the Clean Water Act, and the New York Times reported last week that the agency could make its planned weakening of a major air pollution rule look less deadly by adjusting its math.

"It's just kind of a direction we've been heading since this administration's been in place, rolling back all kinds of environmental protections," Michel says. "They impact all of us. These rollbacks are hurting our economies and our ability to utilize those resources. It's just not good."

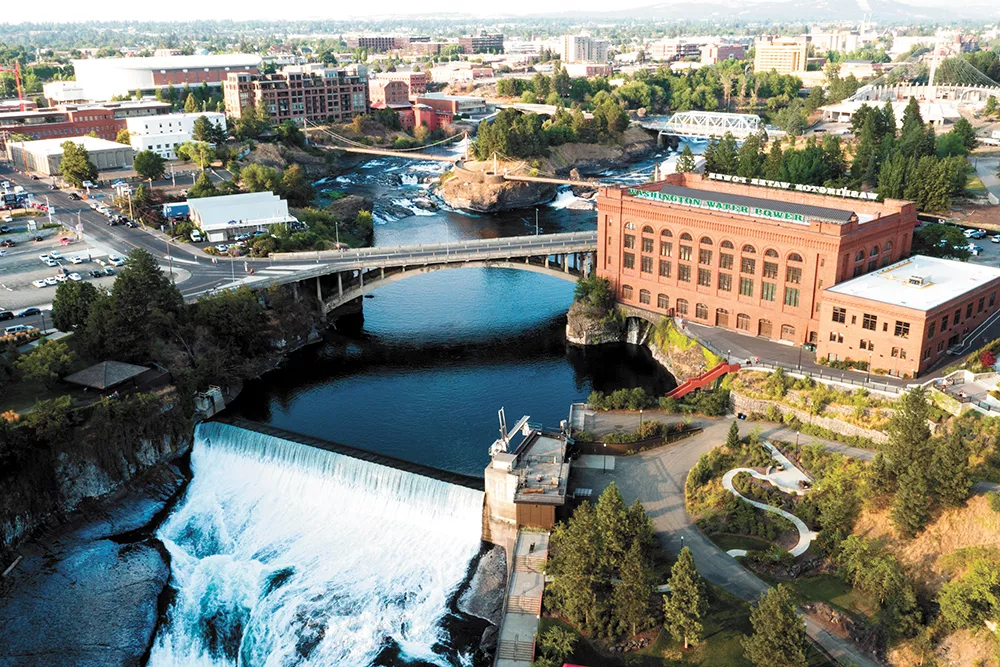

In Spokane, one of the largest pollutants of concern for both dischargers and people concerned with the environment are PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls). The stricter standards for PCBs set by the EPA would limit them to no more than 7 parts per quadrillion. That would revert to 170 parts per quadrillion under the state's old proposal.

"This will dramatically increase the amounts of toxics allowed in Washington's waters, including the Spokane River, and will amplify the health risks to those who regularly fish from the river," says Spokane Riverkeeper Jerry White in a statement. "Some of this rescind pressure has come directly from Spokane's own city governance, congressional representative, and regional industry players. Spokane Riverkeeper stands ready to challenge this development in full force."

Initially, Riverkeeper will work to educate the public and encourage people to comment on EPA's reversal, White says. Legal challenges are also being explored.

"We're certainly investigating what our options are legally," White says.

Part of why the state doesn't want to go back to the lower standards it originally proposed is that regulators have spent more than two years working with polluters to figure out how to meet those strict standards, explains Colleen Keltz, communications manager for Ecology's water quality program.

Just weeks ago, the five main dischargers into the Spokane River — city of Spokane, Kaiser, Spokane County, Liberty Lake and Inland Empire Paper — applied for a variance with Ecology.

"We haven't done a variance before in our state, but that's a type of tool we have to help people meet the standards," Keltz says.

That would get polluters on the path to meeting the stricter standards, setting a schedule and targets to eventually meet that goal, she says. But with uncertainty now on which PCB limits will prevail, things are somewhat up in the air.

Part of what's gotten lost in the media coverage so far is the need to set stricter limits to push technology to advance, says Leonard Forsman, chairman of the Suquamish Tribe and president of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians, a nonprofit that works to improve policies for tribes.

"We need to do all we can to keep our waters clean, and by setting a high standard it will be an incentive for industry to do that," Forsman says. "We need to improve our technology and find better ways to coexist." ♦