Though newspapers have been allowed to continue to operate — dubbed an essential business — they rely on advertising from local businesses. And businesses that aren't allowed to legally operate rarely see the need to advertise — even if they could afford to.

In particular, the crisis represents an existential threat to alt-weeklies like the Inlander, which have been scrambling for ways to find new sources of revenue and hoping loyal advertisers will return — the ones that survive, at least — by the time the economy picks up again.

That led us to seek answers from the past: In 1918, the world was hit with one of the worst pandemics in American history. There was a shutdown then too.

While theaters and churches were closed in Spokane by order of the local health officers, restaurants and department stores largely continued to operate and continued advertising. Even as the death toll rose, the Spokane Daily Chronicle and the Spokesman-Review continued to pump out papers celebrating the virtues of toupees, Shredded Wheat, and Lucky Strike ("It's toasted!").

John Barry's The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, argues that newspapers shamefully underplayed the deadliness and the terror of the epidemic, largely shrugging it off as nothing more than the "nothing more or less than old-fashioned grippe.”

In some cities, Barry writes, that even could even extend to wartime-level censorship.

While there was no such order in Spokane, the number of advertisements that explicitly referenced the pandemic seemed to decline as it progressed. During the months following October 1918 in Spokane, however, numerous department stores, pharmacies and manufacturers found ways to turn the epidemic into profit.

TREATMENTS AND SNAKE OILS

What Viagra ads are to evening TV newscasts today, local pharmacy ads were to the newspapers in the early 1900s.

Even before the pandemic hit, pharmacies were churning out a steady stream of advertisements promising miraculous results from emetics, weight loss drugs, and laxatives.

While this "terrible epidemic is on" another ad proclaimed, don't "leave the house without a bottle of Mentho-Laxene handy."

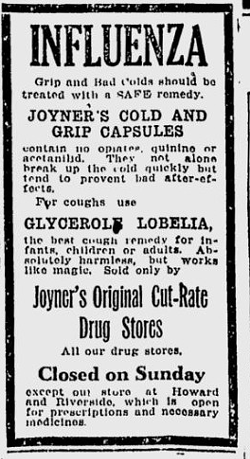

A particular big player in the local ad game was Joyner's Original Cut-Rate Drug Stores, which sold their own branded Joyner's Cold and Grip Capsules as a cure for influenza.

"Most of us, these busy days can not afford, if it can be avoided, to lose a week or more of work so it is all the more necessary that at the very first sign of grip or influenza that counteracting treatment should be taken," Joyner's insisted.

For coughs, they claimed "Glycerol Lobelia" was "absolutely harmless, but works like magic." Foley's Honey and Tar, similarly, was "just what every suffer of influenza or la grippe needs now."

"Every particle of air that enters your breathing organs will thus be charged with an antiseptic healing balsam," Joyner's insisted in Spokane newspapers. "A few cents spent now may easily prevent serious illness and save you many dollars and help stamp out the spread of the disease."

Even back in olden times, doctors considered it quackery: In 1912, the Journal of the American Medical Association scoffed that "this mixture never cured anything, unless it was impecuniosity in its exploiter."

But maybe the most successful ad campaign came from Vick's VapoRub, which dedicated numerous ads in Spokane newspapers to celebrating the ways that the vapors could open up the linings of air passages and "throw off germs."

The ad campaign boosted sales by 300 percent.

"When the Spanish flu hit the U.S. from 1918 to 1919, Vicks VapoRub sales skyrocketed from $900,000 to $2.9 million in just one year," the Vicks VapoRub website proclaims today. "Sales increased so dramatically that the Vicks plant operated day and night to keep up with orders."

But did the VapoRub itself work? Over a century later, the verdict still isn't entirely clear. The Mayo Clinic argues that Vicks' isn't actually effective for decongestion — it just makes it feel like your nasal passageways are being cleared because of the bracing sensations it creates.

For some young children, Vicks may even be dangerous — though another recent study is more encouraging.

"Do not 'fall' for the many advertised 'SURE CURES' for influenza, or so-called tonics to build up body resistance," an ad for the Crescent department store cautioned amid all the other ads for sure cures and body resistance. "Remember, FRESH AIR, REGULAR MEALS, and ABUNDANT REST are what are needed."

This public service announcement, of course, had its own capitalist incentives: The flu advice was under an illustration of a handsome woman hawking "Charming Georgette Crepe Blouses for only $8.76."

The Owl Drug co-published a PSA that advised, among other things, to "keep your bowels open. Intestinal congestion invites disease." But it also sold brand names disinfectants like Platt's Chlorides" and reminded readers that "all Owl Drug Co. salesmen are especially informed as to get able to give you advice on sanitary measures."

A century before Make Your Own COVID-mask tutorials popped up on YouTube, these ads advised how to "Make Your Own Spanish flu" masks with four to six folds of cheesecloth or gauze.

The announcement also served as a help-wanted ad, sounding the alarm for more nurses to volunteer to fight the epidemic.

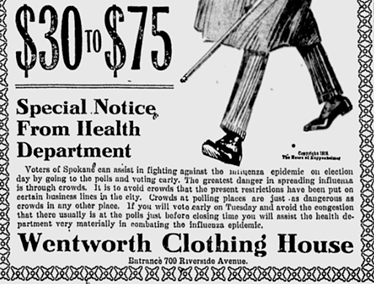

And when the 1918 presidential election was approaching, the Wentworth Clothing Houses took a specific election-era tack, printing a health department notice pleading with voters to avoid influenza-spreading crowds by voting early.

"Crowds at polling places are just as dangerous as crowds in other places," the Wentworth ad insisted.

Spokane's John W. Graham and Co. used the same language, while also stressing that, according to the Council of National Defense, Christmas shopping should be spread out and focused on the early hours to avoid congesting stores and streetcars.

The coronavirus may have slowed down internet speeds, but Spokane telephone companies had a bandwidth problem of a different sort: Turns out those rows of telephone operators packed close together got sick, handicapping the company.

"The larger number of operators now absent because of illness makes it necessary for us to appeal to our people to restrict the use of the telephone," the ad reads "helping the service of war industries, hospitals and stricken homes of our cities."

In fact, as the CDC knows today, you can easily spread the flu before you know you're sick — or when you don't have any symptoms at all.

Other local businesses, however, found a way to use the epidemic to sell more than just drugs.

Life insurance companies used the looming threat of death to paint an image of orphaned children and widowed women

"What if things go wrong?" A Nov. 10, 1918, Western Union Life ad read, "Suppose you should die — of Spanish influenza and other ailments—could your wife pay the mortgages without your income?"

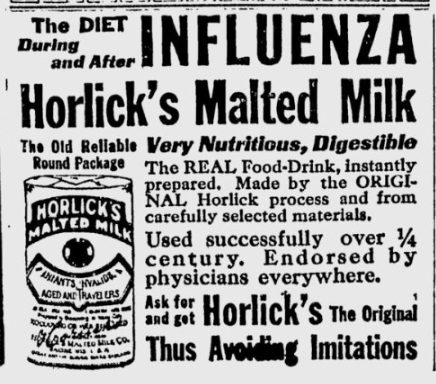

Horlick's Malted Milk touted its "REAL Food-Drink" as the perfect "diet during and after INFLUENZA, and claimed it had been "endorsed by physicians everywhere."

"Men avoid the flu by wearing good shoes that will keep your feet dry and warm," Dolby's Clothing explained.

"In a flu epidemic an ounce of preventive is worth a pound of cure," Hart Schaffner & Marx Clothes Shop explained in their ads for young men's overcoats.

Another key tactic to prevent getting the flu? Imperial Coffee from Gray Manufacturing in Spokane, of course.

"It's helpfulness as a preventative in infections and epidemical diseases under physicians' orders is well-established," the ad explained.

Of course, plenty of ads during the 1918 pandemic didn't have anything to do with the flu at all.

"DON'T risk disappointing someone who expects and needs Corona," an ad in November of 1918.

Of course, back then "Corona" didn't refer to disease or beer. It was a personal typewriter that was all in the vogue in 1918.

"Order your gift Corona now if you wish it for Christmas," the Corona Typewriter Sales Company advised in Spokane. It's advice that we do not recommend following today.