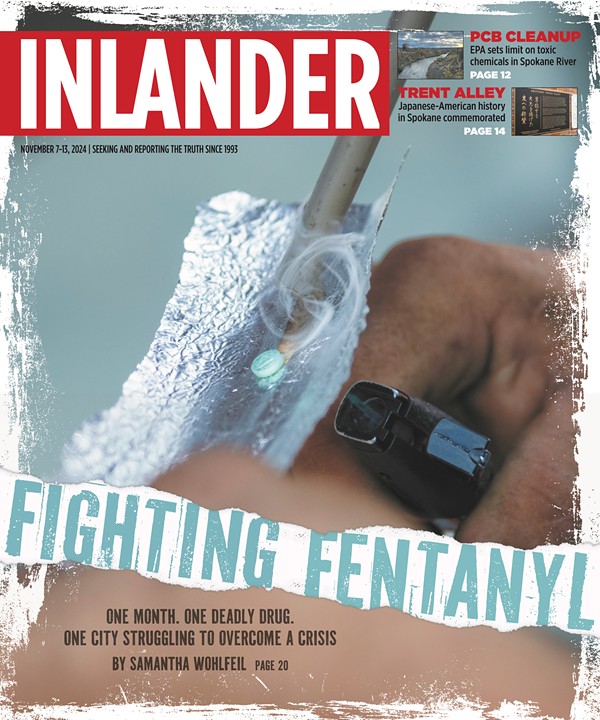

The Inland Northwest will soon see some of the first investments in opioid treatment, prevention and response paid for by settlement money that has started to flow to city and county governments.

Last week, as the largest recipient of opioid settlement money in the region, the Spokane County Board of Commissioners approved spending $7.2 million on four priorities. The list includes $5.2 million to build a new 23-hour crisis relief and sobering space at the existing Spokane Regional Stabilization Center; $1.2 million for behavioral health triage and sobering services; $600,000 for long-term housing and treatment for parents/caregivers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome; and $200,000 per year to track and analyze substance use data.

The money comes from a series of lawsuits filed by state attorneys general against companies that participated in the distribution of prescription opioids. The Washington state Attorney General's Office finished its first settlement in October 2022 and finalized another in January. Other ongoing lawsuits could result in further settlements.

In the 2022 deal, the state secured $518 million (to be paid out over the next 17 years), and required cities and counties to sign onto a statewide agreement to get a share of the money. Local governments were also required to work together regionally to decide where the money could best be spent.

By October 2023, Spokane and five neighboring counties (Adams, Ferry, Lincoln, Pend Oreille and Stevens) created this region's Opioid Abatement Council. Shortly after, they put out a community survey to ask where people — especially those with lived experience or family members who've struggled with addiction — felt the money should be spent.

From that work, staff identified the top priorities and on May 7 the Spokane County commissioners voted 4-0 (Commissioner Mary Kuney excused) to spend most of the roughly $8 million the county has received so far.

"I think that we all know that this epidemic has caused so much damage in our community and all over the nation," Commissioner Chris Jordan said. "The scale of pain for families and victims is immense and these settlement dollars, I believe, are our chance to bring some solutions to the table to promote public health and safety here in Spokane County."

SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS

In Spokane County, overdose deaths involving any drug more than tripled over the last five years, from 80 deaths in 2019 to 301 deaths in 2023, according to the county medical examiner's recently published annual report.The synthetic opioid fentanyl has played a major role in that increase: In 2019, 11 people died from overdoses involving fentanyl; last year that skyrocketed to 194.

But deaths aren't and shouldn't be the only important metric when considering the scope of the problem, says Justin Johnson, director of the county's Community Services Department, which oversees the regional behavioral health administrative services organization. That organization helps respond to and treat people with mental health and substance use issues in the same six counties that are on the Opioid Abatement Council.

"The issue of opiate and fentanyl use, it can't be quantified simply by deaths," Johnson says. "How many times did we prevent a death from occurring, either by first responders, law enforcement, or even family members?"

To better understand and analyze the data in the region, the county commissioners approved spending $200,000 per year to have someone compile opioid information that may currently be siloed. That could include data from law enforcement about the sale and distribution of opioids, and related arrests and incarceration, as well as treatment data from health providers.

When it comes to investing more in treatment, Johnson says many survey respondents said they wanted to see more distribution of naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug. But thankfully, the state is already funding that extensively, Johnson says. Plus, the county has also invested heavily in mental health and substance use treatment options.

"I think people don't realize how much money we've already put out to support substance use and opioid use," Johnson says. "I don't want to wait until we come up with a plan. I want to say, 'There are people in need now, let's put money out there.' And we have done so for the last five years or longer."

SPACE FOR CRISIS RELIEF

The largest investment the commissioners approved last week set aside $5.2 million for a unique 23-hour crisis relief and sobering space. In total, the county expects the new building will likely cost about $10 million to $15 million, and hopes that federal and state money can help cover the rest, says county CEO Scott Simmons.Johnson, meanwhile, has identified funding within the behavioral health organization that can pay for the treatment that will be offered there, regardless of whether someone is on Medicaid or private insurance.

Understanding that the new sobering building will most likely take a few years to complete, but that there is an urgent need already, the commissioners also approved $1.2 million to pay a community agency for that service.

Aside from the hospitals, there's currently nowhere in Spokane County to take someone who is intoxicated so they can sober up and then enter voluntary withdrawal management, says Ryan Kent, the interim executive director for Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services (STARS).

That will soon change. STARS used to offer sobering, and currently offers 38 beds of withdrawal management out of the former Daybreak Youth Services building on South Cowley Street. Downstairs, there's space for the nonprofit to offer as many as 25 to 30 beds for sobering, Kent says.

Sobering typically lasts less than a day. People are offered a warm bed and start to talk to case managers, who can direct them to withdrawal services and get them on the path to more intensive treatment for their substance use disorder, Kent says. At the new STARS facility, there will be a warm handoff to the team upstairs for withdrawal management, which typically lasts three to seven days and allows people time to plan for longer treatment options.

"The priority is to free up the bed space in the hospital," says Kent, who hopes to open the sobering beds within about two months.

The county is expected to put out requests for proposals soon for both the sobering money and the housing for families dealing with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

The second project aligns with plans that the nonprofit Maddie's Place has to build housing on their site near the Perry District to ensure that the parents and infants they serve have a safe home to transition into once those early days of withdrawal are complete. ♦