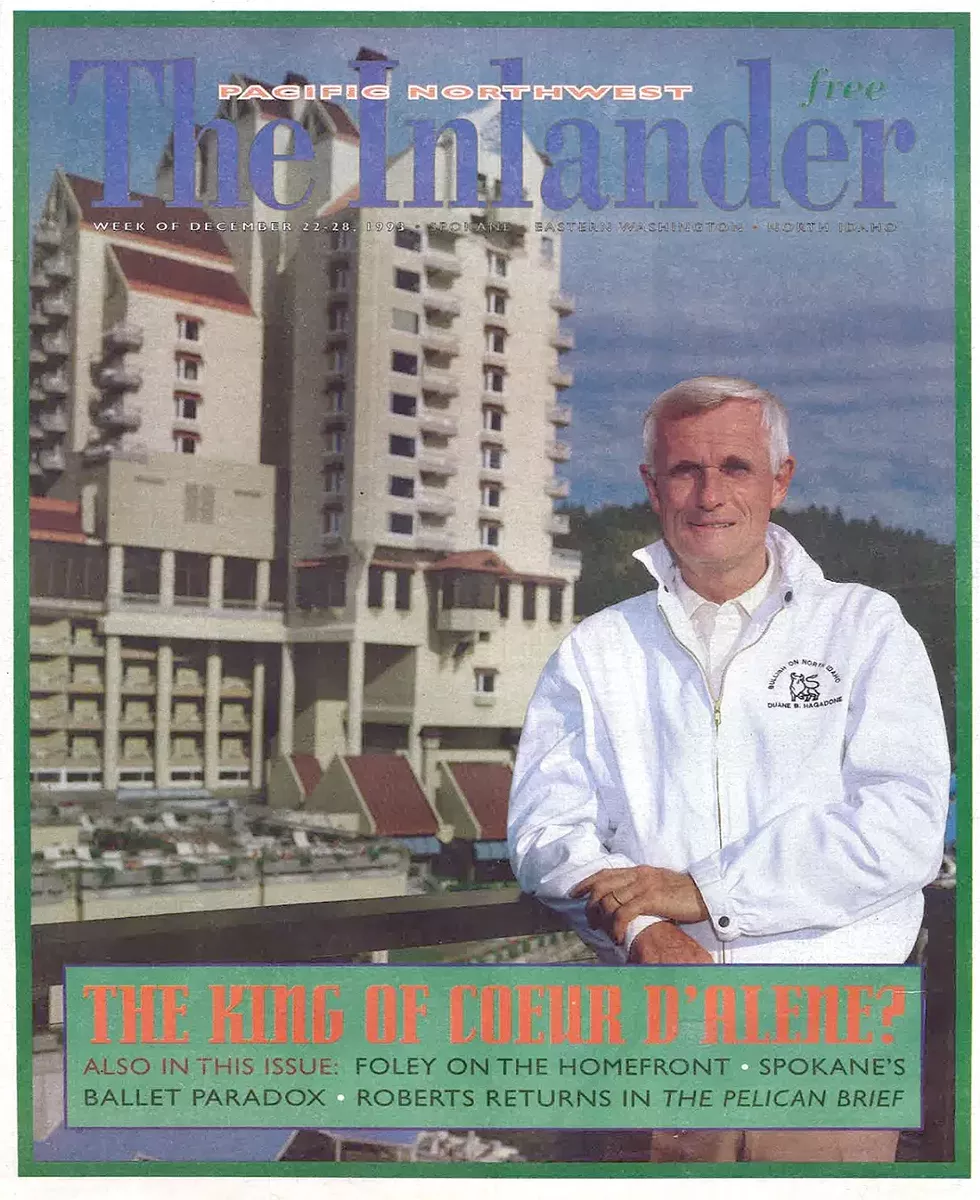

This story first appeared in the Inlander on Dec. 22, 1993. Duane Hagadone passed away on Saturday, April 24, 2021, at the age of 88.

Y

ou might see him on a crisp morning at the controls of his sky-blue ocean racing yacht as it cuts through the light morning fog on his commute to work. Or you may see him driving a ride 'em lawn mower over the meticulously kept grounds of the Coeur d'Alene Resort. Or maybe you'll see him proudly showing wide-eyed visitors from Los Angeles or New York around his new lakeside golf course and one-of-a-kind floating green.Even if you don't see him, it's impossible to miss the signs of his presence all over North Idaho. He and his companies own and operate seven newspapers, two radio stations, two marinas, and four hotels, including the crown jewel of all his holdings — The Coeur d'Alene Resort.

Over the past decade, Duane Hagadone has realized his dreams and in the process has put Coeur d'Alene on the international map. The resort, which dominates the Lake City's waterfront, was recognized as the finest in the world by Conde Nast Traveler magazine in 1990. And the Coeur d'Alene Resort Golf Course wals chosen the best groomed course in the nation by Golf Digest. His pride over these and other accolades is clear — he keeps the magazines in which his properties have been written up neatly lined along a side table in his office, perched high above Coeur d'Alene Lake.

Despite these accomplishments, there's a subtle undercurrent of jealousy and resentment toward him. "It's a company town, and he's the company," says John Rook, one of Hagadone's few outspoken critics.

But in a style common among leaders of business, Hagadone shrugs off the criticisms as simply life at the top in America.

"If I went up to our busiest corner, 3rd and Sherman, and started passing out $10 bills, within two hours there'd be somebody bitching that they weren't $20s. That's just life today," Hagadone says, seated in a high-backed, black leather chair, with the expansive panorama of Coeur d'Alene Lake stretching across the windows of his office behind him.

"I like to tell people I have come a total of three blocks in my life," Hagadone says. "I was born and raised and played on this beach."

T

hrough the criticisms and the accolades, Hagadone believes his investments and projects have benefited North Idaho."I know what I'm doing, and that's what counts," he says with an assured, thin smile.

Hagadone is about as home-grown as they come in these parts. When he was born in Coeur d'Alene 61 years ago, all four of his grandparents lived within city limits. One grandfather was a lawyer from Michigan, the other a North Dakotan with pioneering blood. From his office window, he can see the home he grew up in on Lakeshore Drive.

"I like to tell people I have come a total of three blocks in my life," Hagadone says. "I was born and raised and played on this beach," motioning to the city beach below.

And the roots continue to grow. One of his sons, Brad, is an officer of the company and lives in Coeur d'Alene. Duane and his wife, Lola, split their time between his 20-acre estate just outside Coeur d'Alene and his secluded "cabin" just across the lake from his office.

But Hagadone's journey from being a kid playing on the beach (when he wasn't helping his father, Burl, on the family's newspaper) to becoming a multi-millionaire responsible for a sprawling media empire and a rapidly growing real estate development and hospitality company followed a rather unconventional path.

It is ironic that a man who was inducted into the University of Idaho Hall of Fame didn't even finish a full year there.

"I never did have too much of an interest or an aptitude for education," Hagadone recalls, "but I enjoyed business immensely."

So he left Moscow and returned to Coeur d'Alene where he went to work for his father, who owned shares in four newspapers (then controlled by the Scripps family), including The Coeur d'Alene Press. Hagadone's first real job was selling subscriptions in Wallace, Idaho.

Over the next five years, Hagadone learned the newspaper business from his father, whom he describes as "without question, my best friend." At the early age of 49, cancer claimed his father's life, and Duane, then 26 years old, took the reins of the family business.

In the years that followed, Hagadone managed through a series of buyouts to gain control of those first newspapers, and added some others — from Hawaii to Iowa. By the 1960s, Hagadone's newspaper empire had grown, but new newspapers were becoming more and more expensive to buy. Since tax laws made real estate development an attractive alternative, the Hagadone Corporation turned its attention in that direction.

In the late 1970s, Lake Tower Apartments — the company's first real estate project — was completed. All along, however, Hagadone coveted the North Shore Hotel, primarily for its "world-class" location on the shores of what has been called one of the five most beautiful freshwater lakes in the world.

"There are no free lunches out there today, success only comes from a hell of a lot of hard work," Hagadone says.

W

hen Hagadone built his office building on pilings next to the North Shore 20 years ago, he acquired the right of first refusal on the hotel property from majority owner Bob Templin. Ten years later, in the early 1980s, he was able to buy the property, and the stage was set for the realization of his dream — to build a world-class resort in his hometown.It's hard to believe that the man who dropped out of college to sell newspaper subscriptions is the same man who is now estimated to be worth more than $100 million. But Hagadone bristles at the suggestion that he's lucky — lucky to have been born into a family with money, lucky to have been in the right place at the right time.

He likes to tell the story of how the press hounded golfer Gary Player all through his record-breaking seven consecutive tournament victories. "How long will your luck hold out?" they'd ask after every victory. Finally, Hagadone relates, "Player told them, 'I'm the first on the driving range in the morning and the last to leave. Isn't it ironic that the harder and the longer I practice, the luckier I, get?'

"There are no free lunches out there today, success only comes from a hell of a lot of hard work," Hagadone says, punctuating the moral of the story.

Although not planning to rest on their laurels now, Hagadone Hospitality — the subcompany that controls the resort — has been able to enjoy the taste of an underdog's victory. In not only surviving, but also by becoming a financial success, Hagadone's vision has been vindicated, and the resort's naysayers have been proved wrong.

Inc. magazine skeptically reported on the resort in July of 1986, just two months after it opened.

"There is a chance," the article stated, "that Coeur d'Alene could become the biggest white elephant since William Zeckendorf's Freedomland 22 years ago.''

Then (this is the part Hagadone clearly relishes), in 1991 the editor of Inc. was in Seattle and saw a feature article in the Seattle Times on the resort. He had a reporter do a follow-up story, and Inc. wound up eating its words, since the hotel's occupancy rates surpassed by far what they had projected.

In classic fashion, Hagadone was quoted in the follow-up story saying: "Just try to get a room."

Even sweeter has been proving his traditional cross-state-line rival, the Cowles-owned Spokesman-Review, wrong.

"The Spokesman-Review, on opening day, ran a major piece that we probably would not succeed, and rather than give us a good send off, chose to tear apart our economic vitality," Hagadone recalls.

Although the odds seemed stacked against the project from the start, Hagadone never left anything to dumb luck. He hired the Seattle consulting firm of Pannell Kerr Forster to do a comprehensive project analysis — their most extensive ever — in 1983.

On top of that, Hagadone and his coterie traveled to four-star resorts in Hawaii, California and Oregon and gathered ideas. Hagadone's benchmark was to top the level of excellence they saw in those resorts by 20 percent.

Hagadone enjoys traveling — sometimes in his Learjet — and during his travels he continually takes notes on how things are being done at other resorts to give him ideas about how things could be improved at the Coeur d'Alene Resort. But even after all the preconstruction research, it must have taken some kind of intestinal fortitude to take the final leap of faith and build the hotel since a considerable chunk of the $50 million project was leveraged.

"Before, no one believed in it," Hagadone remembers, "now everyone is on the bandwagon."

"He wants to literally run Coeur d'Alene by his game plan."

L

ike mining, tourism has always been a mainstay for Coeur d'Alene and North Idaho. In 1955 there were 50 hotels in the Lake City. Hydroplane races, a favorable exchange rate and — as always — the spectacular scenery, brought multitudes of Inland Northwesterners, including thousands of Canadians, to town every summer. But by the early 1980s, the nation was in recession, mining was in a funk, and unemployment in North Idaho topped 10 percent.Today, conventioneers from across the country and visitors from all over the world share Coeur d'Alene's busy beaches and sidewalks in the summer with the Inland Northwestemers who have always come to town. And the resort has strengthened its off-season occupancy rates by attracting skiers through package deals with the recently opened Silver Mountain in Kellogg, which is operated by, you guessed it — Hagadone Hospitality.

The resort came into being at an opportune time for the region, says Bob Potter, director of Jobs Plus, North Idaho's business recruitment Organization.

"The investment that Mr. Hagadone has put into North Idaho, and the fact that this was a quality investment, has helped us," Potter says.

With more than 2,000 employees, the Hagadone Corporation is the largest employer between Boise and Canada, and Coeur d'Alene's largest taxpayer. But the kind of notoriety that such a highly rated resort attracts and the fact that Hagadone's vision seems often to become reality has made him something of a lightning rod for people's frustration over increasing property values (and taxes), the influx of newcomers and the community's growing pains.

Increasing numbers of people in North Idaho want to see stronger restrictions placed on new development — a position Hagadone fiercely opposes.

"Back in the early '80s, this community was in tough shape, and that wasn't very long ago," Hagadone says, recalling the days when Coeur d'Alene public schools failed to become state accredited due to lack of funding. "One of the things that hurt me so bad was many of my friends' children who grew up in this area got educated and then could not come back and find work, and had to leave the area. You talk about quality of life, any way you look at it, quality of life begins with a good job."

Kootenai County is currently considering a comprehensive plan that would set rules for growth. Hagadone says that the way the document is currently written will hinder growth.

"We're hopeful they will put some major revisions in it," he says.

Although Hagadone is unabashed about his stance on economic growth and development rights, many think he takes the heat because in a complex and confusing situation, like growth, he is visible and easy to blame.

"I think the resentment in town is for the growth that has happened," says Nancy Sue Wallace, a Coeur d'Alene city council member, "and you can't pin that on Hagadone Hospitality."

AI Hassell, mayor-elect of Coeur d'Alene, says the city is in the enviable position of having homegrown corporations. In many cities in America, the owners of the industries live far away, and therefore have only an economic stake in the community.

"As a whole, we've got a group of community-minded corporate citizens, and that's one of the things that has made Coeur d'Alene what it is," Hassell says.

Scott Reed, a Coeur d'Alene attorney, says that unlike most real estate development companies, the Hagadone Corporation is not in the business of selling what it builds, so its best interests are served by creating projects that benefit the community.

Potter agrees: "I've never seen a company that has put all of its chips — a good chunk of its chips — in one community."

"I certainly didn't have to reinvest the dollars that I have in my hometown," Hagadone says, "but I saw a need for a successful financial venture and an opportunity to help my community."

But many have wondered if Hagadone's patronage is a bit overprotective — if through his newspapers, residents are getting a subjective view of the world, and, more importantly, of North Idaho.

John Rook, owner of the KCDA radio station, has filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice that Hagadone has a media monopoly in North Idaho that is so pervasive it creates a situation in which other media cannot compete. Specifically, Rook charges that Hagadone's Coeur d'Alene newspaper and radio stations used combination selling to undercut KCDA's rates.

"He wants to literally run Coeur d'Alene by his game plan," says Rook, who moved his station to Spokane two years ago.

"The paper lashes out at anyone who gets in the boss's way… [and] fawns over Mr. Hagadone," the article stated.

Additionally, a 1992 Wall Street Journal article on Hagadone questioned how fairly issues are represented in the pages of The Coeur d'Alene Press. "The paper lashes out at anyone who gets in the boss's way… [and] fawns over Mr. Hagadone," the article stated.

Hagadone defends his ownership of so many newspapers in the area, saying that without them, many areas, like Wallace and Kellogg, would likely only have a weekly newspaper. And, he claims, when compared to newspapers serving similar sized communities in other parts of the country, the quality is very high.

A media monopoly is impossible today, Hagadone believes, because there are so many choices through the ever-expanding electronic media. Still, Hagadone publications were the only source of local news in North Idaho until the Spokesman-Review began their push for North Idaho circulation during the past 10 years.

While the struggle for circulation goes on, residents have seen the benefits competition can bring.

"We are well-served by the fact that they are competitive," Reed says, "it has made better newspapers out of both of them."

But Hagadone believes he and his newspaper have the support of the local community, and the fact that the Review is from out of state only helps his case.

"The Cowles family chose a few years back to come to Coeur d'Alene," Hagadone says. "It hasn't worked for them to date, but they've got very deep pockets, and they can keep pushing away as long as they want."

Another criticism that is whispered at (like most things about Hagadone), is that Hagadone has too much sway over local politics. After all, he was able to get a variance for his 18-story hotel in downtown Coeur d'Alene, which is zoned to limit buildings to just three stories. And some wonder whether a city council member who works part time for Hagadone can be truly impartial.

Members of the current city council disagree with these suggestions. "I've never received a call saying, 'vote this way,' 'don't vote this way'," says Wallace, who has been on the council three years.

Hassell, who is finishing his second term on the council, says he has never made decisions based on the merits of the individuals involved, but rather on the issues.

"There are pluses and minuses to living in a small town," Hagadone says of the criticism he takes. "The only people who don't cause some controversy are those who don't do anything."

L

eaning back, relaxed in his office, Hagadone looks like he's already retired. His tanned face sets off his gray hair, and his loose-at-the-collar polo shirt make it seem like he's waiting for a tee time rather than between business appointments."The last thing on my mind today is retirement," he says, "I don't think I'd be a good retiree.''

Although the real estate development aspect of the Hagadone Corporation has taken the front seat in recent years (at least in the eyes of the public), Hagadone says the company is always looking for opportunities within publishing. In fact, the high-profile Hagadone Hospitality only brings in about a quarter of the Hagadone Corporation's total annual income. As lucrative as publishing appears to be, the problem today, he says, is that it's difficult to get a good return on your investment because it's a seller's market.

"All you need to look at is what newspapers are selling for, and, I feel, the fracturing of the electronic media — small- and medium-sized newspapers have got a tremendous future," Hagadone says.

As for the resort, aside from fine tuning what is already there, Hagadone Hospitality has recently announced plans to seek approval to erect a second tower next to the original structure. The new building would add 85 rooms to the complex. They also have long-range plans for adding either a hotel or condominiums at the golf course. And as the resort, and Hagadone's fortune, grows, so does North Idaho. That suits him just fine.

Says Hagadone, "and I see more and more of our young people being able to have quality jobs, and come home to work.

"We don't have to worry about growth being out of control, there're too many governmental agencies and nogrowthers out there to make sure that that does not happen. My concern is that they will overreact and shut it down. In Coeur d'Alene, the economy is much more fragile than many people think.''

The future viability of the area will come through economic growth, Hagadone believes, not just in the form of service jobs like those created by Hagadone Hospitality, but in the form of high-paying manufacturing jobs. Like other city leaders, he believes that Coeur d'Alene cannot thrive on tourism alone.

Hagadone's research shows that North Idaho has 1,000 fewer manufacturing jobs today than it had 10 years ago. He also points out that there are more than 6,000 full-time homebuilders in North Idaho today, and that those boom/bust cyclical jobs won't last forever.

That is why Hagadone helped form and continues to support Jobs Plus. Similar to Spokane's Momentum, it has brought 35 companies and more than 2,000 jobs to North Idaho in the seven years it has been in existence. Its greatest achievement to date has been landing the Harper's Ferry furniture factory, which will relocate to Post Falls in July 1994 and bring 575 new jobs with it.

By anyone's yardstick, Hagadone has, especially through his resort, established a level of excellence and brought a sense of pride to North Idaho that has spilled over into the entire region. As he talks reverently about his past, pointedly on the present state of affairs and with anticipation about the future, it's easy to become entranced by the vision that has been partially cast in concrete just outside his window.

And although the hard work is as obvious as the resort's white tower set against pine-covered Tubbs Hill, and even though he said it isn't any part of the secret of his success, you can't help but think you're looking at a guy who might be just a little bit lucky. ♦

Duane Hagadone passed away on Saturday, April 24, 2021, at the age of 88.