Tim Peone rolls up his sleeve and thrusts his hand into water that's red and squirming with new life.

"Sac fry," exclaims Peone, director of the Spokane Tribal Hatchery, opening his hand to reveal freshly hatched Kokanee salmon flopping about confusedly in his palm.

In about a year, these small fish will be ready for the wild, and hatchery workers will anesthetize them, clip one of their fins (sometimes 10,000 in a day) and release them into Lake Roosevelt where anglers will catch them, their clipped fins indicating they aren't the wild varieties of salmon the tribe once fished.

In one way, the hatchery is a wonder of modern technology, helping the tribe replenish local waterways with fish and reconnecting them with their river heritage.

In another way, though, the hatchery is a bittersweet reminder of the abundance the tribe once enjoyed before the U.S. government dropped slabs of concrete and metal into the Spokane and Columbia rivers, forever changing the diets and culture of local tribes.

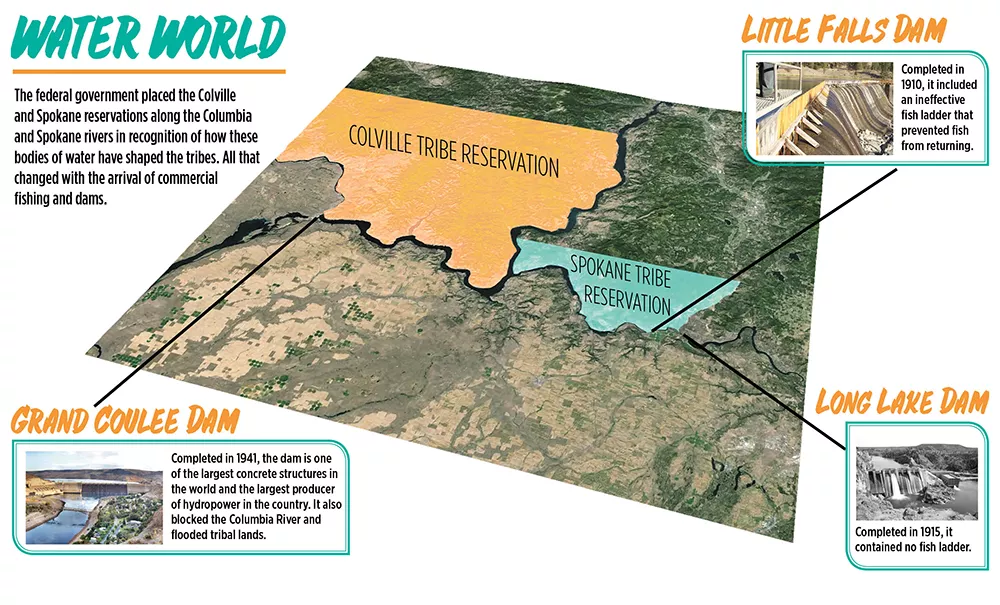

One of these slabs, the Grand Coulee Dam, helped drag the country out of the Great Depression, and the electricity it produced helped win World War II. At 12 million cubic yards of concrete, it's the largest source of hydropower in the country, producing billions of kilowatts of energy every year while directing much-needed water to farms.

After the dam's construction, Peone says the tribe had a series of "lost years" after being abruptly cut off from the defining pillar of its culture. Songs, rituals, ceremonies, honored positions in the tribe and its most basic means of sustenance were all taken from the Spokane people.

"We'll never be fully compensated for the loss of the salmon," Peone says. "There's just no way."

The $4,700 the U.S government gave the tribe in 1940 for the construction of the dam didn't even come close. But for the neighboring Colville Tribe, which had a nearly identical relationship with the river and suffered identical damages, the situation is different.

The Colvilles are getting ready to distribute about $2,000 to each tribe member as an annual payout for the loss inflicted by the dam. The payout is part of a settlement the Colvilles reached in 1994 that gave them an initial $53 million and an annual check for each member based on revenues from the dam.

Meanwhile, the Spokane Tribe, their lobbyists and sympathetic members of Congress are getting ready to mount yet another attempt to right the scales.

For nearly two decades, there's always been some reason, excuse or technicality that's prevented the Spokanes from getting a similar deal. It's an accident of history, and no one, at least not openly, questions the unfairness of the situation. The Obama administration supports a settlement with the Spokanes, as do both of the state's U.S. senators.

Now, the Spokane Tribe and others say the latest barrier is coming from the person who most directly represents them in Congress: Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers.

At the fishery, it's feeding time. Peone watches as a hatchery worker flings fish food into pools stirring with excited fish.

"This area really lost a lot more than people realize," says Peone.

"For us, since time immemorial, we were a river tribe," says Warren Seyler, speaking in a tribal conference room in Wellpinit where a cougar hide hangs on the wall behind him.

Seyler, a 55-year-old member of the Spokane Tribe, served on the tribe's council from 1990 through 2007. Done with tribal politics, his day job is the tribe's Bonneville Power Administration coordinator, serving as the eyes and ears on regulatory issues related to the river. Soft-spoken with a calm demeanor, he beams while telling you all about his interns (tribal members considering careers in wildlife management) after telling you all about a conflict between the Spokanes and the U.S. military in the mid-1800s.

He's well-versed in the tribe's history; the shelves in his office are lined with various books on Indian history, the Lewis and Clark expedition, a copy of A People's History of the United States and a thick tome on the Spokanes' history, along with hefty white binders labeled with red marker and stuffed with historical documents and statistics on regional fish.

With binders and documents spread out on a conference table, he explains that before the dam was built, the Spokanes caught eel, shellfish and salmon from the river. The tribe prayed salmon prayers, sang salmon songs and performed salmon ceremonies on the banks of the river, knowing that the return of the fish meant they could eat another year, Seyler says. Those songs and ceremonies are now lost.

"They knew the science, way back when, that you couldn't take everything," he says.

The harvesting, he says, was overseen by salmon chiefs who said when to start fishing and — because of some medicine, some vision or just the realization that the tribe needed to let some fish go — when to stop. The fish were dried by the ton and shared with everyone.

All of that's gone now, too.

"All I can tell you is that at one time [the Spokane and Colville tribes] had a full-employment economy that was based on their fishery," says Allan Scholz, an Eastern Washington University biology professor. "And that is what is owed those tribes."

Scholz, recently retired, has devoted most of his working life to studying the region's fish and helping tribes, including the Spokanes, build fisheries. He can tell you a lot more.

He can tell you about the Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer that makes the water cool in the summer and warm in the winter, creating an abundance of prey that fish grew fat on. He can tell you about the species of Chinook and coho salmon and steelhead trout that swam out to the Pacific Ocean and then back up the Columbia River after having grown large, sometimes weighing up to 100 pounds. There also were sturgeon and lampreys, and river tribes harvested them all, giving virtually everyone some form of employment and a belly full of fish.

An account from David Douglas, a Scottish botanist who traveled across the Northwest in the early 1800s, describes his visit to an Indian camp along the north side of the Spokane River where the tribe had constructed a barrier of willows that was used to trap the fish, which were skewered with bone-pointed spears. According to his account, 1,700 had been taken that day and sometimes up to 2,000 were harvested daily.

They were speared or caught in baskets. After being cleaned, they were hung up on racks and dried with smoke to preserve them for the winter. All of the work was done with special care. According to one account, if a salmon fell off a spear, the work stopped for the day. If a spear came into the sight of a dog skull (a bad omen), the fisher carrying it underwent a purification ritual.

Settlers tried to pry the tribe away from their way of life almost as soon as they arrived. Protestant missionaries attempted to convince them to abandon their semi-nomadic life and embrace farming and Christianity, with some success. In 1866, a federal agent tasked with trying to convince the Spokane Tribe to enter into a treaty that would relocate them to the Flathead Reservation in Montana wrote that they "will not consent to the abandoning of their fisheries."

Decades later, the Spokanes would end up doing just that because the fish would be gone.

In 1790, according to historians Robert H. Ruby and John Arthur Brown, the Spokane prophet Yureerachen foresaw the coming of the white man, who would come with a book and teach the tribe everything they knew. Then the Spokanes' world would fall to pieces.

Yureerachen's prophecy was borne out. But apparently he left out the parts about the commercial fisheries and the dams.

According to Scholz, the EWU professor, commercial fisheries started to spring up on the region's waterways in the late 1800s, with hundreds of miles of gillnets and fish wheels and no salmon chief to tell them to let some fish go. According to a report from the U.S. Fish Commission, canning operations started up on the Columbia River in 1866 and would harvest 658 million pounds of salmon between then and 1893. The fish wheels, ferris wheel-like contraptions, arrived in 1897. One of them once caught 700,000 pounds of salmon in one day.

"They were just taking every fish in sight," says Scholz.

In 1910, Washington Water Power Co., now Avista, completed the Little Falls Dam on the Spokane River, which Scholz says included an ineffective fish ladder that disrupted the flow of aquatic life. The construction in 1915 of Long Lake Dam, a 200-foot-high dam on the Spokane River, further contributed to the declining fish runs. But it was the Grand Coulee Dam that permanently ended the salmon runs.

The dam's construction began in 1933 as a public works project intended to help pull the country out of the Great Depression, employing 15,000 people during its construction and beginning to generate electricity in 1941, just in time for World War II.

Woody Guthrie was even commissioned to write a song about the dam:

Uncle Sam took up the challenge in the year of 'thirty-three,

For the farmer and the factory and all of you and me,

He said, "Roll along, Columbia, you can ramble to the sea,

But river, while you're rambling, you can do some work for me.

But the river no longer rambled for the tribes. There were no more salmon songs, salmon ceremonies or salmon chiefs. Other tribes no longer congregated to trade buffalo for salmon with the Spokanes during fish runs. The tribe's burial grounds, villages and orchards were submerged under the newly created Lake Roosevelt. (Sometimes when the water level is low in the lake, you can see their washed-up remnants, and every year tribal police have to stop people from picking through the artifacts.)

With the fish dwindling, the government started issuing pork, beef and mutton to the Indians. The tribe's fish-based diet was replaced with foods laden with sugar and salt, according to a report from the World Commission on Dams. Diet-related diseases like diabetes started to appear among the tribe.

The Spokane Tribe shares a lot with the Colvilles. They both spoke dialects of Salish and the loss of the river affected both in similar ways.

"When you have such drastic, quick change in your government, economy, food, what do you do?" asks Mel Tonasket, a 75-year-old member of the Colville Tribe's council.

Tonasket remembers his father telling him of how, as a child, he was put on a wagon with his family and taken on a week-long trip from Omak to Kettle Falls. There, they fished for salmon in a spot reserved for his family. A salmon chief made sure every family had enough to last until the next season. Once the fishing was over, his family started the week-long trip home in a wagon loaded with fish.

His father's generation watched its livelihood vanish, and that sense of loss, says Tonasket, has carried through generations and is palpable today. Alcoholism, domestic violence and so many other problems facing the tribe have their roots in the dam, he says.

"When your providers can't provide anymore, what does it do to you?" he asks.

"We don't really talk about it with our children," Tonasket says of the dam between sips of coffee at the Northern Quest Resort and Casino. He pauses, and looks through bifocals out the window. "I don't know," he continues. "What can you do about it?"

For the Colvilles, there's not much else to do except keep getting the annual checks as part of the settlement over the dam.

Tonasket wears a Navy veteran hat and a blue fleece pullover embroidered with the Colville Tribal Casino logo. It lists the tribe's three casinos, including one at the Grand Coulee Dam. On his right wrist is a purple wristband embroidered with the word "hope."

He was first elected to Colville tribal council in 1970 — eventually becoming chairman — and is serving another term after taking a nearly 25-year break. When he was first elected, he says the dam was a sore point that was seldom brought up. But that changed when he did a stint as president of the National Congress of American Indians in the 1970s, which took him to other reservations where water, particularly in the Southwest, was an increasingly an issue.

All the new talk about water, says Tonasket, prompted the tribe to wonder about their water and what had been done with it. With this realization, the Colvilles, he says, made the decision to start pressing the federal government for a cash settlement over the Grand Coulee Dam.

The tribe's leverage was an open legal claim against the U.S. government for loss of land that dated back to the 1940s. The Spokanes settled a similar claim in 1967 for $6.7 million, which didn't include the dam. The Colvilles hadn't settled their claim. Over the objections of the U.S. government, they amended it in 1976 to include damages from the dam.

Bob Anderson, a former Clinton administration lawyer with the U.S. Department of Interior, now the director of the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington, says the statute of limitations makes it impossible for the Spokanes to reopen a legal claim against the U.S. government over the dam, effectively denying them the same legal leverage that secured the Colvilles' settlement.

He met with the Spokanes during the 1990s and immediately was convinced of the clear justice behind their case. He says that the government has hidden behind "pointy-headed" legal arguments to deny them compensation.

A similar point was made by Kevin Washburn, assistant secretary for Indian Affairs at the U.S. Department of the Interior, during a 2013 hearing to compensate the Spokanes:

"And so in essence, the Colville Tribes got their day in court, but the Spokane Tribe never really did. It is thus largely an accident of history that one tribe was compensated and another tribe was not compensated for the very same loss."

When news broke that the the Colvilles were finally getting a settlement, Tonasket remembers attending a meeting in Nespelem filled with excited people arguing over what to do with the $53 million. According to news accounts, after attorney's fees, each of the tribe's 8,000 members received an initial $6,000, with an annual payment from then on.

The Colville settlement was one of the last legislative acts passed by Tom Foley, a Democrat who represented both tribes in Congress while serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, before he was swept away in the Republican wave of 1994. With a changed political climate in the House, the outlook for the Spokanes also changed.

George Nethercutt was the Republican who unseated Foley. Although more conservative than his predecessor, he was still friendly with the tribes in his district. Nethercutt (also an Inlander commentator) says he developed a relationship with them while working on funding for diabetes research, an issue of interest to the Spokanes, who have struggled with the disease. They gave him Indian blankets as a gift and invited him to give a greeting one year at their powwow in downtown Spokane, which he delivered in mangled Salish. He also became aware of the dam settlement and offered to help.

"I think it goes to fairness," says Nethercutt, who became a lobbyist after leaving Congress in 2004 and whose clients included the Spokanes.

In 1999, he introduced legislation that would have given the Spokanes compensation for the dam, but it ended up going nowhere, a process that was repeated twice more. In 2003, Washington Senator Maria Cantwell, a Democrat, managed to get a compensation bill passed through the U.S. Senate, only to see it stall in the House.

In 2005, the bill passed the House, but was attacked by Lincoln County officials for how it would transfer some of the jurisdiction along Lake Roosevelt back to the tribe. It ended up stalling in the Senate. In 2009, the Spokesman-Review published an article raising concerns about how the settlement could again create access problems to the lake, prompting the Spokane Tribe to take out a full-page ad attacking the article.

Howard Funke, the tribe's former lawyer, recalls these articles creating a backlash against McMorris Rodgers, who replaced Nethercutt in 2005 and had been working on the legislation.

A compensation bill has been introduced in every Congress since then, and it seemed like it would finally pass in 2013. Cantwell had the gavel on the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. The Obama administration had thrown its support behind it, with Washburn acknowledging before the committee that the Colvilles receiving compensation and the Spokanes being left out "is difficult to justify morally, frankly."

But the bill never came up for a full vote in the Senate.

Funke says it's hard to question how unfair the situation is, but there are members of Congress who just don't want a settlement.

"Believe you me, there are senators in Congress who really dislike Indian tribes," he says. "And all it takes is for a senator to anonymously put a hold on a bill. Maybe they want to save the government some money; it doesn't matter why, but the bill is dead in the water."

At the hatchery hang black-and-white 1980s photos of Tim Peone and his brother Rudy, both with long mullets, working on fish-related projects while studying under Allan Scholz at EWU. There's also a framed letter from Tom Foley, apologizing that he couldn't make it in person to its opening in 1990.

Rudy Peone, who serves as the tribe's chairman, drives down the gravel driveway to the hatchery in a big white pickup truck. He prefers to meet here because part of being tribal chairman means people who need help with an electric or phone bill coming in and out of his office all day.

"I don't know," says Peone, 44, with a salt-and-pepper goatee, of why the tribe can't get compensation. "It's beyond me — it's excuse after excuse."

Nowadays, the most recent excuse, says Peone, is that compensating the tribe is an "earmark."

Earmarks used to be a way for members of Congress to provide companies, projects and organizations direct funding with federal tax money. But House Republicans got rid of them outright in 2011 as part of an overall anti-spending atmosphere that pervaded the chamber when they took over.

Peone says that there is bipartisan support for the bill, but members of Congress want McMorris Rodgers, the fourth-highest ranking House Republican, to take the lead on it.

In the past, she has. In 2005, she took the floor of the House to speak in favor of an unsuccessful compensation bill.

"Mr. Speaker," said McMorris Rodgers, "This bill has bipartisan support and is the result of lengthy discussions for over a decade."

Now, when contacted by the Inlander to ask about the bill, her office responds with emails saying that the legislation contains an earmark, which are not allowed, and wouldn't comment further.

In recent years, there's been some friction between the Spokanes and McMorris Rodgers over a proposed tribal casino near Fairchild Air Force Base that the congresswoman says encroaches on its space. Peone says that's a side issue that has nothing to do with the settlement and reiterates that he wants to work with her.

"I'm still going to go back to Cathy," says Peone. "She is my and my tribe's representative, and I'm going to continue to request that she fight on behalf of her constituency."

Nethercutt isn't so diplomatic. "To be frank with you, I didn't buy that argument," he says of the claim that the settlement is an earmark. "That's a cop-out. You just don't want to spend the money."

Peone can only speculate what would happen if they reached a settlement. He'd like to build a cultural center that will help reconnect tribal members with their heritage, particularly their Salish language.

Like many members of the tribe, Peone knows a few words in Salish, but is far from fluent. When asked what the word for "salmon" is in Salish, he searches his mind. It's almost on the tip of his tongue when he turns to Tim for help.

"That's a good one," his brother says. He doesn't know the answer either. ♦