From one view, Spokane City Councilman Michael Cathcart's proposed addition to the city's housing action plan on July 26 was sweeping and radical: Temporarily legalize not just duplexes, but also triplexes and fourplexes in every single residential neighborhood of the city.

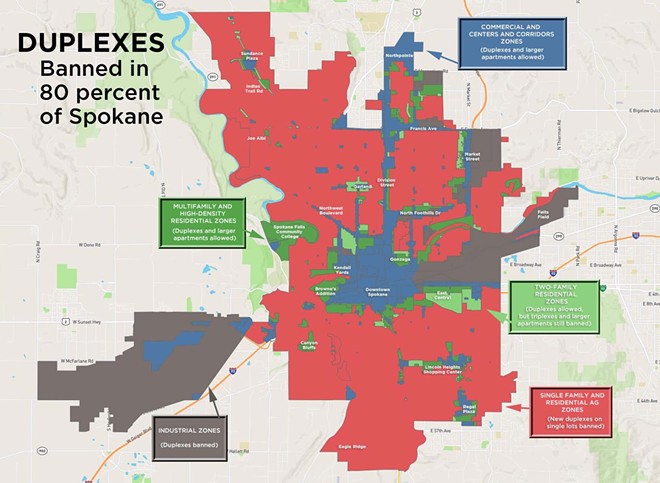

Right now, building multiple units on a single lot is illegal in 80 percent of Spokane — including the 60 percent of the city that has been dedicated to low-density "single-family residential" zones.

The entire nation has been struggling with a housing shortage, but it's been particularly bad in Spokane: In July, Spokane had the second-highest rent increase in the nation.

"We have an opportunity to hopefully do something to make a difference," Cathcart said during the July meeting. If it was a housing emergency, he argued, it was time to take emergency measures.

His proposal sharply divided the council, not along conservative or liberal lines, but along how the city should grow and how much control neighbors should have over surrounding density.

Councilwoman Candace Mumm was visibly upset by the ramifications of Cathcart's proposal to go around the typical process.

"In no way are we going to explain to our neighborhoods how in one night with no notice are we going to change the landscape of the entire city," Mumm said. "It's too extreme and it's certainly not something I can support."

Ultimately, three of the seven councilmembers sided with Cathcart, enough to include their support for duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes "on a list at the back of the housing action plan." But to make it an actual emergency ordinance — the sort that would bypass the lengthy development process and take effect almost immediately — he needed five votes. With Council President Beggs and Councilwoman Lori Kinnear joining Mumm in opposing Cathcart's amendment, the impact would be more symbolic than immediate.

"We continue to discriminate against those forms of housing," Cathcart says.

And for now, changing that would mean winding through a lengthy community process involving the council, city staff and the citizen-led Plan Commission. It could take years.

"It's time for bold action. Council — on a 4-3 — said we need urgent action now," Cathcart says. "And nothing is happening."

Last week, the entire state of California passed a bill guaranteeing property owners the right to construct as many as two duplexes on single-family lots across the state. Two years earlier, the state of Oregon passed a similar bill.

But Washington state remains the lone West Coast holdout to allow cities to ban duplexes in "single-family" zones.

"The Association of Washington Cities and the Association of Washington Counties are really powerful at the state level," says Ben Stuckart, executive director at the Spokane Low-Income Housing Consortium, an association that promotes affordable housing. "And they put a kibosh on anything that takes away local control."

But Stuckart also knows exactly how difficult it is to get those kinds of measures passed at the local level.

Stuckart led the City Council for eight years, from 2011 to 2019 — managing to get a veto-proof 6-1 majority of progressives — but he never got enough votes to do the kind of whole-scale zoning reform he thinks is necessary today.

"Clearly with the housing crisis in the state, local control isn't working," says Dan Bertolet, a research director at the pro-housing activist group Sightline.

The issue splits the left, Stuckart notes. Left-wing Councilwoman Kate Burke enthusiastically supported the conservative Cathcart's policy, seeing it as part of reforming the "structurally racist" single-family-zoning ordinances that had historically been used to perpetuate segregation.

But loosening housing regulations can just as easily be tarred as something that gives developers more power and strips neighborhoods of their influence.

"This is exactly what the lobbyists have been waiting for, is this moment," Mumm, a moderate liberal compared to Burke, argued at the July meeting, "So they can wipe out all the public process, all the thousands of people who worked to build up the community, without having their voices heard."

At one time, local leaders could argue legalizing duplexes wasn't just necessary, it was patriotic. After the United States entered World War II, the city of Spokane passed a temporary emergency zoning ordinance to address the local housing crisis sparked by the surge of workers moving here to assist the war effort. As long as the war lasted, the duplexes would be legal in single-family zones. Many of the bigger houses in historic districts like Browne's Addition, Cannon's Addition and Nettleton's Addition were divided up into apartments during this time, Spokane housing history buff Logan Camporeale says.

But Spokane's more recent history is filled with examples of neighborhoods making duplexes and triplexes politically toxic.

"This is exactly what the lobbyists have been waiting for, is this moment."

tweet this

When a developer asked to rezone some of his properties in the Indian Trail neighborhood to allow duplexes in 1997, angry neighbors threatened to put up signs that would say "duplexes and renters are unwelcome" in their front yards. In the mid-2000s, developers were using zoning that allowed duplexes to create ad-hoc boxy additions to homes in the Logan neighborhood to take advantage of the demand for student housing. But neighbors were furious, calling the duplexes a "disgrace" that was "degrading" and causing "destruction of the neighborhood." The City Council ultimately downzoned part of the area to a single-family zone.

And when Stuckart came into office in 2011, he says, he was focused on giving those neighborhoods more power to thwart developers, not less.

"I probably came into council more neighborhood-oriented for sure: 'Listen to the neighborhoods, they should have veto power,'" Stuckart says. "But I think the crisis in housing has become more acute, so you'll see more people changing their mind."

While Spokane's rents aren't nearly as expensive as Seattle, Portland or San Francisco, our apartment unit availability is far worse: Spokane only has one available unit for every 200 apartment spaces, a rental market almost 10 times tighter than Portland.

Today, Lindsay Shaw, chair of the Logan neighborhood, says she recognizes the seriousness of the housing crisis.

"I know that some people on a certain side of town have squawked a ton about having fourplexes coming into their neighborhood like it would ruin it. I don't think it's gonna ruin our neighborhood," says Shaw. "But I just hope that, if they do it, they do it citywide and not just in the lower-income neighborhoods."

John Schram, the co-chair of the Comstock neighborhood council on the South Hill, is less sympathetic to the city's efforts, arguing that the city needs to get its own house in order, focusing on issues like addressing traffic problems, "rather than all these grand ideas with little impact."

Asked why neighbors would be concerned if the ideas have little impact, Schram says that they're worried that minor tweaks would lead to larger, more obtrusive ones.

Sometimes the opposition to duplexes and triplexes has come in the form of concerns over traffic and parking. Other times, Stuckart says, the concerns are more classist — he shares one anecdote about a moment where half the opposition to a South Hill zoning change melted away as soon as the developer revealed how expensive the homes he planned to build would sell for.

But just as often the opposition is mostly aesthetic. Shaw talks about the neighborhood's desire to make sure duplexes or fourplexes fit with the architectural character — to fit the surrounding neighborhood — rather than just sticking out as some blocky cookie-cutter duplex built during a housing emergency. Guarantee that duplexes or triplexes won't be ugly through design standards, and you dampen a lot of those neighbor's fears.

"I think that does go a long way toward mitigating an underlying concern," Schram says.

But Mumm's concerns are more long-term: Before running for council, she had served as president of the city's Plan Commission for a decade. She'd help codify the city's "centers and corridors" strategy, the one that tried to push commercial and denser residential development toward arterial roads and a limited number of neighborhood hubs, like the South Perry district.

"We want these centers to be vibrant, to have them become walkable and socially active centers," Mumm says. "I have seen the fruits of that investment."

Legalizing triplexes and fourplexes everywhere could dilute those efforts, she worries, along with straining utilities.

On the other hand, compared to other major Washington state cities, Spokane was by far the worst at building enough housing to keep up with our last decade of population growth, according to Kevin Schofield, writer at the Seattle City Council Insight blog,

Seattle added new housing units almost as fast as they added new residents. Yet Spokane? Our population grew two and a half times faster than our rate of housing growth.

The Plan Commission's current president Todd Beyreuther argues that the centers and corridors strategy is "somewhat dated," noting that people can "weaponize it by saying, 'outside the centers and corridors, we won't have any density.'"

For two years, he says, he's tried to push the commission to support more forms of housing in single-family zones, with limited success.

"It's been hard," says Beyreuther. "There's a lot of ways to slow roll if you're opposed to it."

Cathcart hopes that his addition to the city's housing action plan will make it clear to both the commission and the city staff that the council supports allowing up to four units on every residential lot city-wide.

Longtime city planner Louis Meuler says the city's planning department expects to bring forward the first wave of code amendments next year — which may include support for legalizing duplexes on corner lots. But Meuler suspects it would take longer to kick off the process to discuss controversial pieces of the housing action plan, like legalizing triplexes and fourplexes. Those would require changes to the city's long-term "comprehensive plan" — a process that usually takes at least a year or more to complete.

Stuckart estimates it's a "three-year public education process led by the city from the start to finish."

While developers who've built duplexes, like Terra Homes' Steve Edwards, welcome some of the city council's tweaks to allow for more density, they also say they're not nearly enough to address Spokane's housing crisis.

"Us in the industry are saying, 'We're just rearranging the chairs on the Titanic," Edwards says, "We're not really getting where we need to be." ♦