Imagine this: You're voting on a matter of national significance, you get to the front of the line, and the poll worker asks, "What state are you from?"

Montana? Great, you get a full vote for or against the measure.

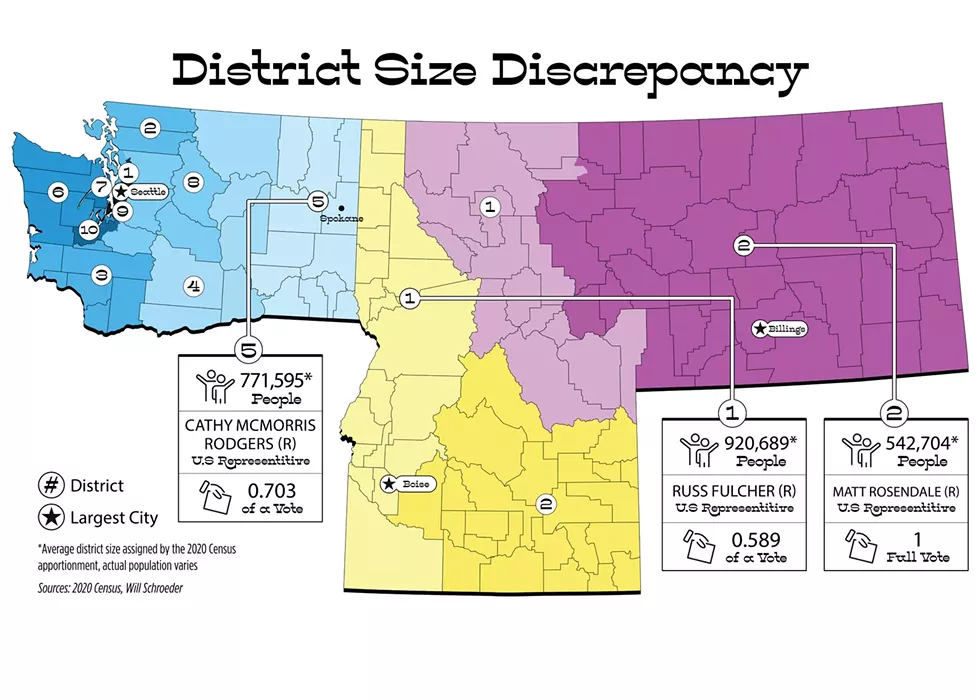

Washington? OK, you get just under three-quarters of a vote.

Idaho? Welp, you get a little over half of a vote.

Wait... what? Why would some votes count less just because of the state you live in? How is that fair?

It's not.

But in effect, that's exactly how disparate the public's voting power currently is in the U.S. House of Representatives, because congressional districts vary so dramatically that the largest district has nearly half a million more people in it than the smallest district.

While court cases in the 1960s established that congressional districts within a state need to be basically equal in size, recognizing the principle of "one person, one vote," the same standard hasn't been applied to districts across the country. Other than requiring at least one representative for each state, with at least 30,000 constituents per representative, the U.S. Constitution leaves plenty of leeway for Congress to decide just how big the House should be and how its members should be apportioned "according to [states'] respective numbers" of residents.

Neighboring Northwest states perfectly illustrate the divide that has grown in recent decades.

As of 2022, Montana has the smallest House districts in the country, with each of the state's two representatives covering about 543,000 people. Before gaining a seat during the 2020 apportionment, the state had only one district of nearly a million people, making Montanans' voting power, through their representative, the weakest in the country. Now, it's the strongest.

Meanwhile, Washington's 10 U.S. representatives have about 772,000 constituents in each of their districts.

Idaho is currently the second-worst represented state in the country, with each of its two representatives covering almost 921,000 as of 2020. (Delaware gets the saddest slice of the vote cake, with only one representative covering nearly 991,000 people.)

Spokane attorney Will C. Schroeder, who most often handles trial cases such as wrongful death lawsuits, stumbled upon the dramatic difference in the size of House districts across the country in early 2022 after his kids asked him to explain: How does the government work?

"I started with a dad joke: 'Not very well,'" Schroeder says.

After explaining the executive and judicial branches, and the Senate, which is made up of two senators from each state, Schroeder says he realized his knowledge was a little fuzzy when it came to the House. He told them that seats are split out based on population ... basically ... and there are currently 435 districts.

When his kids asked, "Why 435?" Schroeder says he had to answer, "Well, I don't specifically know."

So he did some research. What Schroeder found ultimately led him to file a lawsuit against the U.S. government in mid-2022, arguing that virtually every voter in the country has had their constitutional rights infringed. District size is so varied that the idea of "one person, one vote" has been violated.

In his research, Schroeder learned that, while Congress used to increase the number of representatives after each census, doing so for the better part of 100 years, the House stopped adding representatives after it reached 435 members in 1912.

Because the population growth in each state varies, and districts can't be split between multiple states, the mathematical Method of Equal Proportions isn't able to create perfectly balanced districts. While most districts in the country sit somewhere in the 700,000 range, 12 states have districts that sit outside that range.

Schroeder's proposed solution? Since each state needs to have at least one representative, why not use the population of the smallest state (currently Wyoming, at about 580,000 people) to set the size of districts, and add more members to keep districts about that size?

"For the longest time, that's just how I assumed it worked," Schroeder says. "Every district should be the same size."

Using that method, Idaho would get a third representative (due to its growth, the state is already poised to get that third seat after the 2030 census) and Washington would get three more representatives. Overall, the House would grow to about 570 members.

Schroeder says there may be many unknowns with how that could impact politics, but because of the principle, we should give it a shot, because what we have now creates imbalances.

"The more people are in a district, the less access you have, practically, to your representative," he says.

After his case was dismissed in U.S. District Court due to lack of standing, Schroeder appealed. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has asked to hear oral arguments in Seattle later this year. Schroeder hopes that the appellate judges will weigh in on some of the merits, even if the case ultimately gets dismissed, which he thinks is likely.

"What I'm hoping is that they see that there's something to this, too," Schroeder says, "and that they write a robust decision."

A NOVEL, CREATIVE THEORY

It's possible that one of the reasons there hasn't been an appetite for increasing the size of the House over the last century is due to the impracticality of having a larger governing body, says Jason Gillmer, who teaches constitutional law at Gonzaga University.

"The House, as it was tracking population growth, had the potential of increasing the numbers of representatives so much that it would become an unruly governing body — to the extent that it is not already. I think that's why they settled on that number," Gillmer says. "Obviously that's a good question: How many is too many? ... There's no magic number."

There are also practical limitations: The House Chamber would likely need to be expanded to add any members, and new offices would be needed for each of them and their staff.

Plus, there would be more salaries to pay.

Most senators and representatives make $174,000 per year (it's more for the handful in leadership), and every House member gets about $1.9 million per year to pay for their staff, office expenses, travel to their district, and mailings, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Regardless of any practical limitations on expanding the House, Schroeder's lawsuit raises an important question, Gillmer says.

"Our collective influence over government has been diluted over the years because of how many people a representative has to represent," Gillmer says. "He's also no doubt right that some states have more representation because of population size."

One of the cases Schroeder cites heavily in his appeal is Wesberry v. Sanders. In that case, voters in Georgia's 5th Congressional District took issue with the fact that their district had two to three times the population of other congressional districts in their state, diluting their votes.

In 1964, the Supreme Court ruled in Wesberry that congressional districts within each state must have roughly equal populations, pointing to plenty of historical context that shows the framers intended the House to be equally representative, with "one person, one vote" guiding the equal sizes of districts, or at-large voting for seats.

"While it may not be possible to draw congressional districts with mathematical precision, that is no excuse for ignoring our Constitution's plain objective of making equal representation for equal numbers of people the fundamental goal for the House of Representatives. That is the high standard of justice and common sense which the Founders set for us," the ruling states.

But that case only applied to intrastate district sizes, not interstate district discrepancies.

Still, Schroeder is hopeful that the same logic from that case applies nationally.

The Supreme Court decision in Wesberry states, in part, "To say that a vote is worth more in one district than in another would not only run counter to our fundamental ideas of democratic government, it would cast aside the principle of a House of Representatives elected 'by the People,' a principle tenaciously fought for and established at the Constitutional Convention."

"His theory is, 'Well, if that's true of a state, surely it would have to be true of the nation as a whole,'" Gillmer says. "It's a novel theory, it's a creative theory."

It'll be an uphill battle to get a ruling to affirm that theory though. Schroeder's case was dismissed in federal District Court for lack of standing. However, he appealed, and the 9th Circuit has agreed to hear oral argument on the case sometime in May or July, rather than just dismissing it on similar grounds as the District Court.

Meanwhile, the federal government, represented by the office of Vanessa Waldref, U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Washington, continues to argue that Schroeder has no standing and that the courts can't decide how Congress should be constructed, as it's a political question.

"In fixing the size of the House at 435 Representatives, Congress balanced the need to have enough members to be broadly representative against the need to have a functional legislature," states the government's Dec. 20, 2023, brief. "Schroeder asked the district court to overturn the Congressional compromise of a multifaceted problem that has no precise solution and, in so doing, to restructure an entire branch of the federal government at its most fundamental level. Courts lack the power to do so."

The federal brief also points out that a similar case calling to add representatives to the House to address population disparities, Clemons v. Department of Commerce, went to the Supreme Court in 2010 and was dismissed because the court lacked jurisdiction.

"The Supreme Court confirmed that the size of the House is not subject to challenge in Clemons," the federal brief argues. "While the Supreme Court did not specify the precise jurisdictional flaw in [Clemons], those plaintiffs raised a challenge similar to Schroeder's, and a similar disposition is therefore warranted here."

At first, when Schroeder saw Clemons, he thought he might be out of luck with his attempt to have his complaint heard in court. However, because the court didn't weigh in on the merits in Clemons, and a ruling in the 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause reaffirmed that courts could weigh in on "one person, one vote" cases, he feels confident the court can weigh in on the merits here.

"All the court's technically being asked to do is declaratory relief: say whether it's constitutional or not," Schroeder says. "It looks like you can at least get at some of our equal representation problems without having to amend the Constitution, which is a bit of a relief."

MORE HISTORY AND A LOOK AHEAD

Back in 1787, the framers at the Constitutional Convention were big on the whole concept of "no taxation without representation," and they devised a decennial census to count all the people in each state with the idea of fairly assigning representatives based on population. To make sure no one had the motivation to fictitiously report a larger population in order to get more members of the House, the count also came with a tax burden. Taxation, hand-in-hand with representation.

It's also important to remember that for the first 100-plus years, the Senate received two members from each state who were elected by state legislatures. It wasn't until 1914, after the 17th Amendment was ratified, that senators were first elected by popular vote like representatives.

From the outset, Article 1 of the Constitution guaranteed that each state would have at least one representative, and no representative should have a district smaller than 30,000 people. Early House members (through 1833) had 34,000 to 50,000 constituents each, and they were elected to at-large positions by voters in their state.

By the mid-1800s, the voting switched to district-based House seats, in an attempt to have even more localized representation.

Of course, early census data used to set the overall number of House members was problematic. It counted only the "whole number" of people per state, with Black people counted as 3/5 of a person (a compromise with Southern states that wanted more representatives even though slaves were not allowed to vote), and excluding Native Americans who weren't taxed.

While Article 1 set a minimum size for districts, it didn't set a cap. And it didn't dictate how many members could or should be in the House.

Though it's not an apples-to-apples example, by way of comparison, the U.K.'s House of Commons today has 650 members representing about 63 million people in Parliament. The U.S. has nearly 336 million people.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court's decision in Wesberry outlines some of the mistakes of the British Parliament (which was also soon to be reformed) that delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 hoped to avoid repeating. They especially wanted to avoid what were known as "rotten boroughs" — communities that had extremely outsized representation in Parliament.

"[James] Wilson urged that people must be represented as individuals, so that America would escape the evils of the English system, under which one man could send two members to Parliament to represent the borough of Old Sarum, while London's million people sent but four," the 1964 ruling says of what was shared during the convention.

You might be thinking, what do our regional representatives think about this whole idea of expanding the House? Well, we tried multiple times over the last few weeks to talk to U.S. Reps. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., and Russ Fulcher, R-Idaho, but after emailing their staffs specific questions and trying to schedule a phone call multiple times, we didn't hear from either representative.

Regardless of what happens with Schroeder's lawsuit, Shasti Conrad, chair of the Washington State Democratic Party, says she doesn't think it's likely that Washington will get additional representation in Congress anytime soon. (The Washington GOP did not provide comment after multiple requests.)

Conrad would rather focus on other reforms, such as moving Washington's local elections from odd years to even years so there's greater participation in things like city council elections that are more likely to impact people close to home.

"There are far more realistic goals related to electoral reform that are much closer to actually being able to make an impact," Conrad says. "One of those, I think, is moving to even-year elections."

She also thinks Electoral College reform is picking up steam around the country.

Another quick civics refresher: The number of electors assigned to each state is determined by the number of members of Congress a state has (one for each senator and representative). Schroeder thinks that part of the disparity between the popular vote and what's been seen in the electoral vote has to do with the House being capped at 435, making districts uneven by population. So, if Schroeder wins his lawsuit, it could directly impact the Electoral College, and the way we elect our presidents. ♦

PAID FOR LIFE?

For what it's worth, that myth you've heard about people serving just one term in Congress and earning their salary for life is just that: a myth. Salaries are paid only during the terms that members are elected to. However, full annual pensions are offered starting at age 62 to those who've served for at least five years, starting at age 50 for those who've served for 20 years and at any age for someone who's served 25 years. According to the Congressional Research Service, each member vests into the plan based on their total years of service, and pays about 1% to 4% of their salary per year into the plan depending on the year they started in office. No member can receive more than 80% of their final salary as their pension, and under the current rules, you'd have to serve 66 years to vest to that full 80%.

With the announcement last week that U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers will be leaving office at the end of this year, she could be eligible for an immediate full pension, since she's 54 and this will be her 20th year serving in Congress. If she accepts it, her pension could be $59,160 per year.

— SAMANTHA WOHLFEIL

A CENTURY AT 435

As envisioned by the framers of the Constitution in 1787, the once-per-decade census was created in large part so that Congress could figure out how many representatives there should be, based on the population.

For more than a century, Congress added House members each decade as new states joined the union and the population grew. Every representative initially covered about the same number of constituents, which was roughly 34,000 to 50,000 people per representative during the first 50 years, when representatives were elected to at-large seats by state. That grew to almost 174,000 constituents per representative over the next 50 years as members started serving districts.

Over time, the House grew from 65 members serving 13 states in 1790, to 241 members serving 25 states in 1836, and to 391 members serving 46 states in 1907.

But since 1912, the House has remained at 435 members. The number was updated to 433 after the 1910 census, allowing for two additional members should Arizona and New Mexico become states. Both did in 1912. (The House temporarily grew to 437 members from 1959 to 1963 to accommodate one member each for the new states of Alaska and Hawaii until the 1960 census was used to reapportion the 435 members.)

There's some complicated, xenophobic history involved, but part of why the number stalled at 435 is that Congress rejected the 1920 census and heavily debated whether immigrants should be counted in population totals used to apportion House seats. By 1929, Congress passed the Permanent Apportionment Act, setting 435 as the permanent number and ensuring that seats would be reapportioned among the states after every census, whether Congress acts or not.

While the House hasn't grown in 112 years, the U.S. population has tripled, from about 92 million in the 1910 census to more than 331 million in 2020. Representatives in 1913 served an average of about 211,000 constituents. In 2023, the average was about 761,000 constituents.

For much of the 20th century, the mathematical "Method of Equal Proportions," which was devised in the 1940s to divvy up the 435 seats, seemed to give states roughly similarly sized districts. But Spokane attorney Will C. Schroeder says the population divide between the smallest and largest districts in the country has grown dramatically since the early 1990s.